By Karin Peterson

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc, Winter 2012-2013

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

Neither the Emancipation Proclamation nor Connecticut legislation related to freeing enslaved Africans guaranteed equal treatment and opportunities for those freed. The Connecticut Freedom Trail was established by the General Assembly in 1995 as a way to recognize African Americans’ and other minority populations’ fight for freedom and social equality here in the state and to mark sites that represent milestones representing key events in that quest.

Whereas relics of the white majority population’s past are highly visible around us, the tangible record of African Americans’ and minorities’ experience is less obvious. The struggle to maintain human dignity leaves no physical evidence; success often is signaled by gaining freedom or getting an education. The sites along the Connecticut Freedom Trail reflect such disparities; the trail is not a catalog of pretty, restored historic houses!

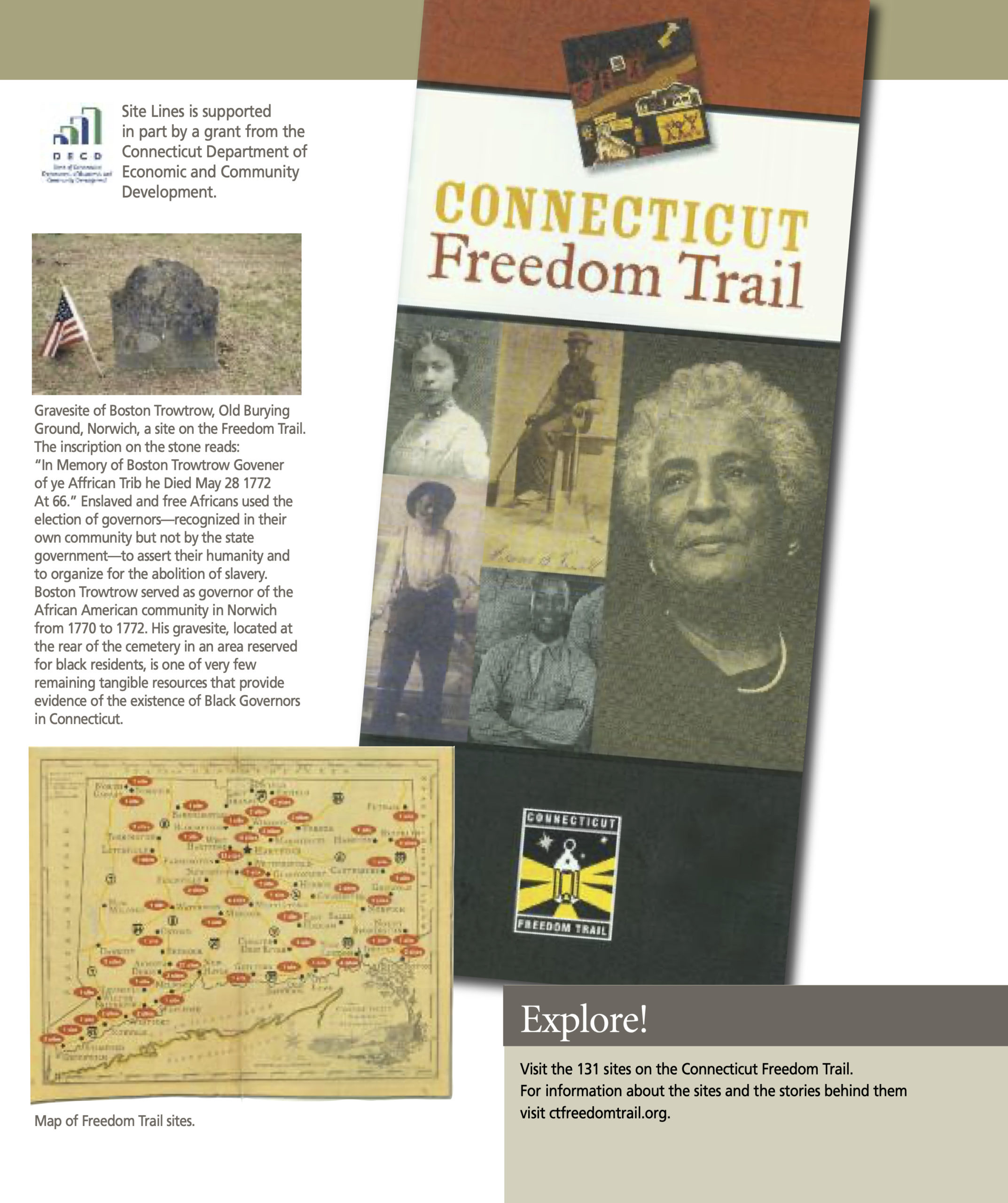

Approximately ten percent of the Connecticut Freedom Trail’s sites are individual gravesites, and nearly the same number of sites are cemeteries with multiple African American burials. These record for posterity the lives of individuals who do not appear in the official town histories. A simple brownstone marker in New London’s Antientist Burial Ground, for example, marks the grave of Florio [Flora] who died in April 1749 at age 60. According to the inscription, she was the wife of Hercules, “governor of the Negroes,” referring to the 18th- and early 19th-century tradition by which Connecticut’s African Americans elected their own leaders. This New London gravestone is the earliest reference to the custom.

It is known that elections were held in May in several towns with large African American populations, including Hartford, New London, New Haven, and Norwich. In some towns this elected official appeared to have power to enforce law and order among the local black inhabitants. The individual selected was usually a free servant or enslaved man belonging to an influential white family. Boston Trowtrow, for instance, was Norwich’s black governor from 1770 to1772; he was owned by Jabez Huntington, a wealthy merchant and prominent leader in colony politics, and his son, Jedidiah, who served as a general under General Washington in the Revolutionary War. Trowtrow’s gravesite is on the Trail.

Churches serving black congregations played a critical role in African American communities and are well represented on the Trail. (See the Summer 2011 issue’s “Fortresses of Faith, Agents of Change” and Summer 2005’s “Faith Congregational Church: 185 Years, Same People, Same Purpose.”) In addition to providing spiritual comfort, churches met secular needs by providing opportunities for political action and socializing and sometimes sponsoring schools.

Each Freedom Trail site provides a window into the past as experienced by the state’s African Americans. One challenge black people in Connecticut faced was discrimination in purchasing property. The Leverett Beman Historic District in Middletown is a triangle of land bounded by Vine and Cross streets and Knowles Avenue. In 1847 Leverett Beman (1810-1883) laid out these five acres as a planned neighborhood with 11 lots. This is the first documented residential development by an African American for African American homeowners in Connecticut.

Leverett came from a remarkable family. His father, Jehiel Beman, was the son of a slave who earned his freedom by serving as a soldier in the Revolutionary War. A shoemaker and itinerant minister, Jehiel was called in 1830 to be the first pastor of Middletown’s Cross Street A.M.E. Zion Church (also a Freedom Trail site). Jehiel became such an active leader in the abolitionist movement that his church was called the Freedom Church. In 1833 his son Amos applied to Wesleyan but was denied admission. Undaunted, Amos paid for private tutoring by a sympathetic Wesleyan student, an arrangement that lasted six months. Amos went on to become a prominent pastor like his father, and, also like his father, he was active in the abolition movement. Leverett worked as a shoemaker with Jehiel at their shop on Williams Street. He endeavored to improve the quality of the lives of African Americans by making home ownership possible for them. (See “A Family of Reformers: The Middletown Bemans” in the Winter 2008/2009 issue.)

The Trail currently comprises 131 sites in 48 towns; new sites are added regularly. Inclusion on the Trail does not require owners to open their property to the public, nor does it provide any funding or tax benefits. The intent is to honor these sites and to identify them as historically significant. Administration of the Connecticut Freedom Trail is shared by the State Historic Preservation Office of the Department of Economic and Community Development and the Amistad Committee, Inc. of New Haven.

Karin Peterson has served as the museum director for the State Historic Preservation Office for more than 10 years. She is a member of the Connecticut Explored editorial team and a frequent contributor to the magazine.

Explore!

Visit the 131 sites on the Connecticut Freedom Trail. For information on the sites and the stories behind them visit ctfreedomtrail.org.

Connecticut Explored received support for this publication from the State Historic Preservation Office of the Department of Economic and Community Development with funds from the Community Investment Act of the State of Connecticut.

Connecticut Explored received support for this publication from the State Historic Preservation Office of the Department of Economic and Community Development with funds from the Community Investment Act of the State of Connecticut.