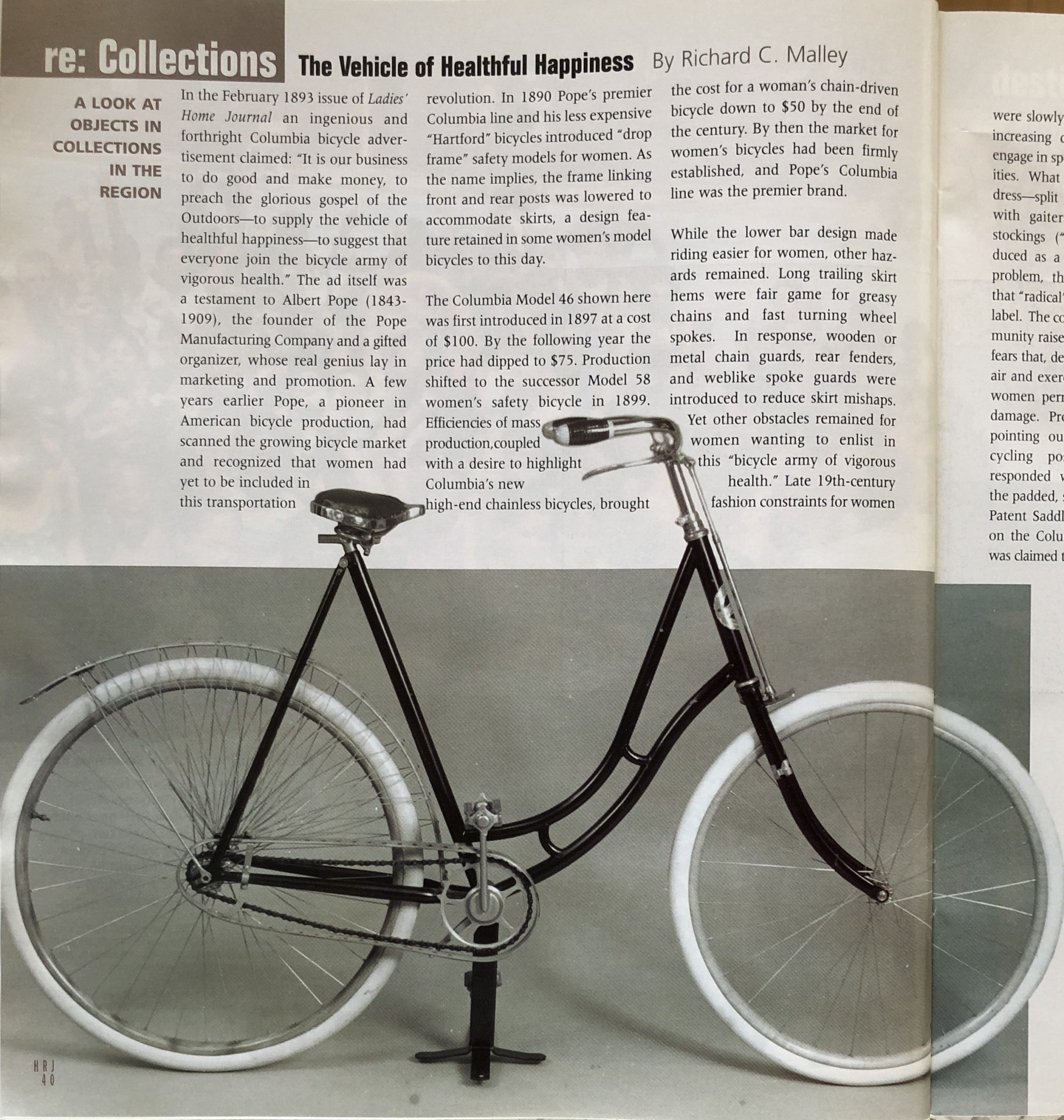

Columbia Model 46 Woman’s Safety Bicycle, Hartford, 1898. This restored bicycle features a wooden chain guard and rear fender, netted spoke guard, and an optional Christy Patent Saddle. photo: Art Kiely, Connecticut Historical Society, Hartford

RE: Collections — A Look at Objects in Collections

By Richard C. Malley

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Spring 2003

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

“To men, rich and poor, the bicycle is an unmixed blessing, but to the woman it is deliverance, revolution, and salvation.”

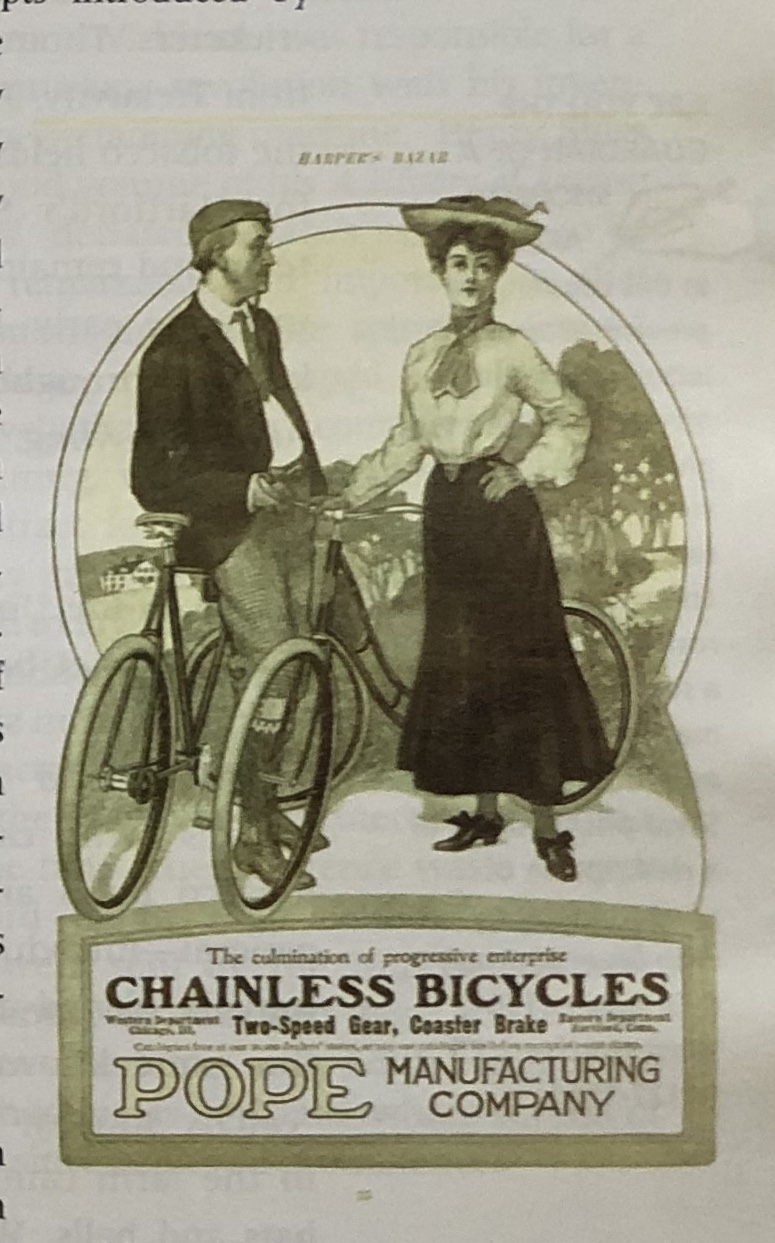

In the February 1893 issue of Ladies’ Home Journal an ingenious and forthright Columbia bicycle advertisement claimed: “It is our business to do good and make money, to preach the glorious gospel of the Outdoors — to supply the vehicle of healthful happiness — to suggest that everyone join the bicycle army of vigorous health.” The ad itself was a testament to Albert Pope (1843-1909), the founder of the Pope Manufacturing Company and a gifted organizer, whose real genius lay in marketing and promotion.

A few years earlier Pope, a pioneer in American bicycle production, had scanned the growing bicycle market and recognized that women had yet to be included in this transportation revolution. In 1890, Pope’s premier Columbia line and his less expensive “Hartford” bicycles introduced “drop frame” safety models for women. As the name implies, the frame linking the front and rear posts was lowered to accommodate skirts, a design feature retained in some women’s model bicycles to this day.

The Columbia Model 46 shown here was first introduced in 1897 at a cost of $100. By the following year, the price had dipped to $75. Production shifted to the successor Model 58 woman’s safety bicycle in 1899. Efficiencies of mass production, coupled with a desire to highlight Columbia’s new high-end chainless bicycles, brought the cost for a women’s chain-driven bicycle down to $50 by then end of the century. By then the market for women’s bicycles had been firmly established, and Pope’s Columbia line was the premier brand.

While the lower bar design made riding easier for women, other hazards remained. Long trailing skirt hems were fair game for greasy chains and fast turning wheel spokes. In response, wooden or metal chain guards, rear fenders, and weblike spoke guards were introduced to reduce skirt mishaps. Yet other obstacles remained for women wanting to enlist in this “bicycle army of vigorous health.” Late 19th-century fashion constraints for women were slowly loosening in the face of increasing demands by women to engage in sporting and exercise activities. What was termed “rational” dress — split skirts, calf-length skirts with gaiters, even knickers with stockings (“bloomers”) — was introduced as a solution to the bicycle problem, through traditionalists felt that “radical” was a more appropriate label.

The conservative medical community raised other issues, including fear that, despite the benefits of fresh air and exercise, cycling could cause women permanent spinal or pelvic damage. Proponents countered by pointing out the benefits of good cycling posture, and inventors responded with developments like the padded split seat design “Christy Patent Saddle.” This seat, an option on the Columbia Model 46 bicycle, was claimed to prevent pelvic injuries.

How had this rapid evolution in personal transportation and recreation occurred? When Bostonian Alfred Pope established the Pope Manufacturing Company in 1877 he was, in today’s parlance, “pushing the envelope” by investing in the manufacture of an unproven product — the bicycle. A risk taker by nature, the 35-year old Pope believed that a vast market would develop for an affordable type of personal vehicle. Idea in hand, Pope looked southward to Hartford, a well-established center of mass-produced precision items, from firearms to sewing machines. Production of his all-metal “Columbia” line of bicycles began at the old Weed Sewing Machine Co. plant in Hartford’s Frog Hollow neighborhood in 1878, effectively launching the American bicycle industry.

High-wheel bicycles, with their distinctive tall front wheel and small rear wheel design, were the first products of Pope Manufacturing. But advances in bicycle technology occurred with amazing speed, and in 1885 a bicycle with wheels of equal diameter was developed in Britain. Pope and other manufacturers quickly saw where the future lay and began introducing their own models of the so-called “safety” bicycle. Doubters soon admitted that besides being much easier to ride, the chain-driven safety bicycle was also faster and more maneuverable. Employing mass-production techniques and specialized machine tooling, Pope was able to undertake true mass production of bicycles. By the 1890s, Pope’s 3,000 employees were turning out 60,000 bicycles annually, thereby reducing costs and broadening both the domestic and foreign markets.

Among Pope’s last major advances in bicycle development was the introduction of the Columbia Chainless bicycle in the mid-1890s. Based on concepts introduced by Hartford’s League Cycle Company in the early 1890s, the new design eliminated a lingering problem for women by replacing the exposed chain with an enclosed gear and drive-shaft arrangement. For a variety of technical reasons the chainless design was not successful, and chain-driven bicycles continued to dominate the market.

By the early 20th century, when Pope began to turn his attention from bicycles to automobiles, he had left an indelible mark on the social fabric of the day. His championing of recreational cycling for women provided another “plank” in the developing platform for women’s rights and suffrage in the new century. As a Cosmopolitan writer, reflecting on the ongoing cycling battle, noted in the August 1895 issue, “To men, rich and poor, the bicycle is an unmixed blessing, but to the woman it is deliverance, revolution, and salvation.”

Richard C. Malley was assistant director of museum collections at the Connecticut Historical Society.

Read More!

“The Fastest Men on Two Wheels,” Fall 2009

More about Pope Manufacturing — “The Miracle on Capital Avenue,” May/Jun/Jul 2004

The Connecticut Brand Collection

6 issues: $35 (a $49 value!)

This collection features stories on Connecticut’s manufacturing and industrial history. You’ll read about products—some well known, some surprising—that were made or conceived in Connecticut. Delve into the places and people that made these products, and how Connecticut’s manufacturing past impacted the day-to-day lives of Connecticut’s people in places like Bridgeport, New Britain, Waterbury, and more!

May/Jun/Jul 2004 – All in a Days Work

Spring 2005 – Made in Connecticut

Fall 2007 – We Made It!

Winter 2011-2012 – Connecticut Abroad

Winter 2013-2014 Connecticut At Work

Winter 2015-2016 That’s a Connecticut Brand?