(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Winter 2017-2018

From VALIANT AMBITION: George Washington, Benedict Arnold, and the Fate of the American Revolution by Nathaniel Philbrick, published on May 10, 2016 by Viking, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC. Copyright © 2016 by Nathaniel Philbrick. Purchase Valiant Ambition at penguinrandomhouse.com/books/316034/valiant-ambition-by-nathaniel-philbrick/.

“In the winter of 1777, Benedict Arnold fell in love,” best-selling historian Nathaniel Philbrick begins chapter 4 of his 2016 book Valiant Ambition: George Washington, Benedict Arnold, and the Fate of the American Revolution. But that’s not why we’ve selected a part of this chapter to excerpt in this issue about love, hate, and rivalry in Connecticut history. What happens later in the chapter, after the 36-year-old widower was rebuffed by 16-year-old Elizabeth Deblois of Boston, is a window into Arnold’s love/hate relationship with his home state of Connecticut and how rivalries fueled his eventual turn against it during the American Revolution.

Arnold’s grievances and frustrations were mounting that winter of 1777. He was already considering a move from the Continental army to the navy, when, as Philbrick writes,

He received stunning news. Not only had the Continental Congress decided not to award him his expected promotion; it had promoted five brigadier generals past him to the rank of major general. … [General George] Washington was both embarrassed and appalled on Arnold’s behalf. …Washington eventually learned that the promotions had been based on a newly instituted quota system by which each state was allotted two major generals. Since Connecticut already had two officers of that rank, the Continental Congress, in its wisdom, had determined that their top-ranking brigadier general, who also happened to have the best record in the army, should suffer the humiliation of watching five of his lesser peers move past him in the ranks. … At Washington’s repeated urgings, Arnold promised to do nothing rash but admitted that he could not help but ‘view [the nonpromotion]as a very civil way of requesting my resignation.’

Arnold went to New Haven in the spring of 1777 to visit his sister, check on his businesses, and see his three young sons. He planned to go on to Philadelphia to argue his case before Congress. But fate intervened. New York’s royal governor William Tryon decided to do what British commander-in-chief William Howe failed to—go after and destroy the rebels’ stockpile of provisions and military stores in Danbury. The following is excerpted, by permission, from Valiant Ambition: George Washington, Benedict Arnold, and the Fate of the American Revolution.

Thirty miles up the Connecticut coast, Benedict Arnold was attempting to enjoy his time in New Haven. Back in January, when he had stopped by on his way from Washington’s headquarters on the Delaware to his assignment in Rhode Island, the citizens of New Haven had hailed him as a conquering hero. For the son of a bankrupt alcoholic, it had been a heady time.

This visit, however, was different. His recent humiliations—in both love and war—were the talk of the town. The unfinished mansion on the New Haven waterfront that he’d begun building prior to the Revolution—paneled with mahogany from Honduras, with stables for twelve horses and an orchard of a hundred fruit trees—had become a sadly dilapidated monument to his declining fortunes.

And then, on the afternoon of April 26, just as he prepared to begin the long trek to Philadelphia, Arnold received word that the British were headed to Danbury.

By the night of April 26, Howe’s men had marched almost completely unopposed to Danbury, where they proceeded to destroy 1,700 tents, 5,000 pairs of shoes, 60 hogsheads of rum, 20 hogsheads of wine, 4,000 barrels of beef, and 5,000 barrels of flour, as well as putting torch to more than forty houses. The town’s meetinghouse, it was discovered, was also “full of stores,” and that too was consigned to the flames.

Later that night, after an almost thirty-mile ride in the rain, Arnold rendezvoused with generals David Wooster and Gold Silliman and about six hundred militiamen in the town of Redding, about eight miles to the south of Danbury. Knowing that Tryon’s path back to his ships at the mouth of the Saugatuck River would likely take him through Ridgefield, Arnold and Silliman resolved to march to that town with four hundred men while Wooster and a smaller force harassed the rear of the retreating British. The hope was that Wooster could delay the enemy long enough to allow Arnold and Silliman the time to prepare a proper reception.

At a narrow point in the road through Ridgefield, bounded by a steep rocky ledge on one side and a farmhouse on the other, Arnold oversaw the construction of a breastwork made of wagons, rocks, and mounds of earth. Around eleven in the morning, Wooster, sixty-six years old and a veteran of the French and Indian War who had had his differences with Arnold while in Canada, bravely led his men against the enemy’s rear. A British officer later remarked that the elderly general “opposed us with more obstinancy than skill.” Before Wooster had a chance to fall back, he received a musket ball in the groin. His son rushed to his aid, and when a regular bore down on the two of them, the younger Wooster refused to ask for quarter and, according to the British officer, “died by the bayonet” at his mortally wounded father’s side.

In the meantime, Arnold hastened to prepare his tiny force of less than five hundred militiamen, instructing them to hold their fire until the British were well within range. As Tryon approached at the head of a column that extended for more than a half mile behind him, he realized that “Arnold had taken post very advantageously.” The American general might have a much smaller force of mere militiamen, but dislodging them was not going to be easy. At that point, Tryon requested that the more experienced William Erskine, whom Tryon regarded as “the first general [in the British army]without exception,” assume command.

Instead of assaulting Arnold’s well-prepared force head-on, he sent out flanking parties that worked their way far enough to the edges of the breastwork that they were able to fire directly on the militiamen. With nothing between them and the enemy’s musketballs, the militamen began to retreat. All the while, Arnold continued to ride his horse back and forth along the fragmenting American line in an attempt to form a rear guard that might protect the men as they fall back.

Arnold once claimed that “he was a coward till he was fifteen years of age” and that “his courage was acquired.” The son of a devout Congregationalist mother who frequently harangued him about the inevitability of death, he appears to have become convinced that he was somehow immune to the perils that had claimed four of his siblings and left only himself and his sister Hannah to grow into adulthood. The year before, when he lay in a makeshift hospital bed in Quebec with his left leg in a splint and with two pistols at his side in the event of a surpise attack by the enemy, he had insisted in a letter to Hannah that the “Providence which has carried me through so many dangers is still my protection. I am in the way of my duty and know no fear.”

As had been proven at Valcour Island and now at the little town of Ridgefield, this was no idle boast. His men were fleeing all around him but Arnold refused to yield. His horse was ultimately hit by nine different musket balls before the stricken animal collapsed to the ground. His legs ensnared in the stirrups, Arnold struggled to untangle himself as a well-known Connecticut loyalist rushed toward him with a fixed bayonet. “Surrender!” the loyalist cried. “You are a prisoner!” Reaching for the two pistols in the holsters of his saddle, Arnold was reputed to have said, “Not yet,” before shooting the loyalist dead. He soon extricated himself from the stirrups and escaped into the nearby swamp.

Tryon, with Erskine’s help, had easily defeated the Americans. His soldier, however, were exhausted, leaving him no choice but to encamp near Ridgefield and continue the march the next morning. That night Arnold conducted a quick council of war and with Silliman’s help prepared to lay another trap for his enemy.

By delaying the enemy at Ridgefield, Arnold had given his Connecticut countrymen the time required to descend upon the British invaders. “The militia began to harass us early… and increased every mile, galling us from their houses and fences,” a British officer wrote. “Several instances of astonishing temerity marked the rebels in this route. Four men, from one house, fired on the army and persisted in defending it till they perished in its flames. One man on horseback rode up within fifteen yards of our advanced guard, fired his piece and had the good fortune to escape unhurt.”

By that time, Arnold had been joined by his friend John Lamb and his artillery regiment, the corps that Arnold had helped finance with the loan of a thousand pounds back in February. Now that he had three fieldpieces at his disposal, Arnold found a section of high ground about two miles north of Norwalk that commanded a fork in the road through which Tryon must pass. According to a witness, Arnold had “made the best disposition possible of his little army.” Unfortunately, a loyalist became aware of Arnold’s position and, knowing of a place on the Saugatuck River that was fordable, led Tryon’s soldiers across the river just to the north of the roadblock.

By that time, Arnold had been joined by his friend John Lamb and his artillery regiment, the corps that Arnold had helped finance with the loan of a thousand pounds back in February. Now that he had three fieldpieces at his disposal, Arnold found a section of high ground about two miles north of Norwalk that commanded a fork in the road through which Tryon must pass. According to a witness, Arnold had “made the best disposition possible of his little army.” Unfortunately, a loyalist became aware of Arnold’s position and, knowing of a place on the Saugatuck River that was fordable, led Tryon’s soldiers across the river just to the north of the roadblock.

Momentarily foiled, Arnold led the attack on the rear of the fleeing British, who had by the late afternoon reached the relative safety of Compo Hill overlooking Long Island Sound, where the fleet of warships and transports awaited. Throughout the day, Arnold had been his usual daredevil self. “[He] exposed himself almost to a fault,” a witness wrote, “[and]exhibited the greatest marks of bravery, coolness, and fortitude.”

Once the regulars had been reinforced with some fresh troops from the transports, Tryon and Erskine determined to disperse Arnold’s militiamen before they began loading their soldiers onto the ships. It was then, a British officer recalled, that Major Charles Stuart “gained immortal honor.” What Stuart realized was that Lamb and his friend Eleazer Oswald—both of whom had been with Arnold at Quebec—had nearly completed a makeshift battery for their three six-pounders. They must attack before the cannons could begin firing. With a vanguard of just a dozen men, Stuart led a bayonet charge of more than four hundred regulars that quickly overran the rebel position. Lamb and Oswald did their best—the British officers commented that their fieldpieces “were well served”—but when Lamb, who’d already lost an eye during the assault on Quebec, was hit in the side by a round of grapeshot, the Americans began to retreat.

Once again, Arnold showed no qualms about putting himself in harm’s way and, according to a witness, “rode up to our front line and [ignoring]the enemy’s fire of musketry and grapeshot [exhorted us]by the love of themselves, posterity, and all that’s sacred not to desert him, but … all to no purpose.” For the second time in as many days, Arnold had a horse shot out from underneath him while a musket ball creased the collar of his coat. Even the British were impressed. “The enemy opposed with great bravery,” an officer marveled, “many opening their breasts to the bayonets with great fury and our ammunition began to be very scarce.”

The British considered Tryon’s raid on Danbury a great success. The Continental Congress appreciated the valiant attempt by Arnold, Wooster, Silliman, and the local militia to defend Connecticut and inflict damage on Tryon’s troops. In recognition of Arnold’s bravery and leadership, Congress reconsidered its treatment of Arnold. In early May Arnold was promoted to major general—but Congress tempered the honor by insisting he be granted lower seniority than those promoted above him in February.

A year later, Washington put Arnold in command of Philadelphia, which had been recently evacuated by the British. There, Arnold met and married 18-year-old loyalist Peggy Shippen in 1779. Proceeding to live beyond his means, Arnold was later court-martialed for using his position for financial gain. In 1780 and in command of the army’s position at West Point, he secretly prepared to turn West Point over to the British. The plot was discovered, but he escaped and became an officer in the British army.

Four years after the Battle of Ridgefield, on September 6, 1781, Benedict Arnold would trade roles with Tryon and lead the British attack on New London—just 14 miles down the Thames River from his hometown of Norwich. Read that story in “Benedict Arnold Turns and Burns New London” in the Fall 2006 issue or online at ctexplored.org/benedict-arnold-turns-and-burns-new-london/.

Nathaniel Philbrick won the National Book Award for In the Heart of the Sea: The Tragedy of the Whaleship Essex (2000) and was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize for History for Mayflower: A Story of Courage, Community, and War (2006).

Explore!

Purchase Valiant Ambition at penguinrandomhouse.com/books/316034/valiant-ambition-by-nathaniel-philbrick/.

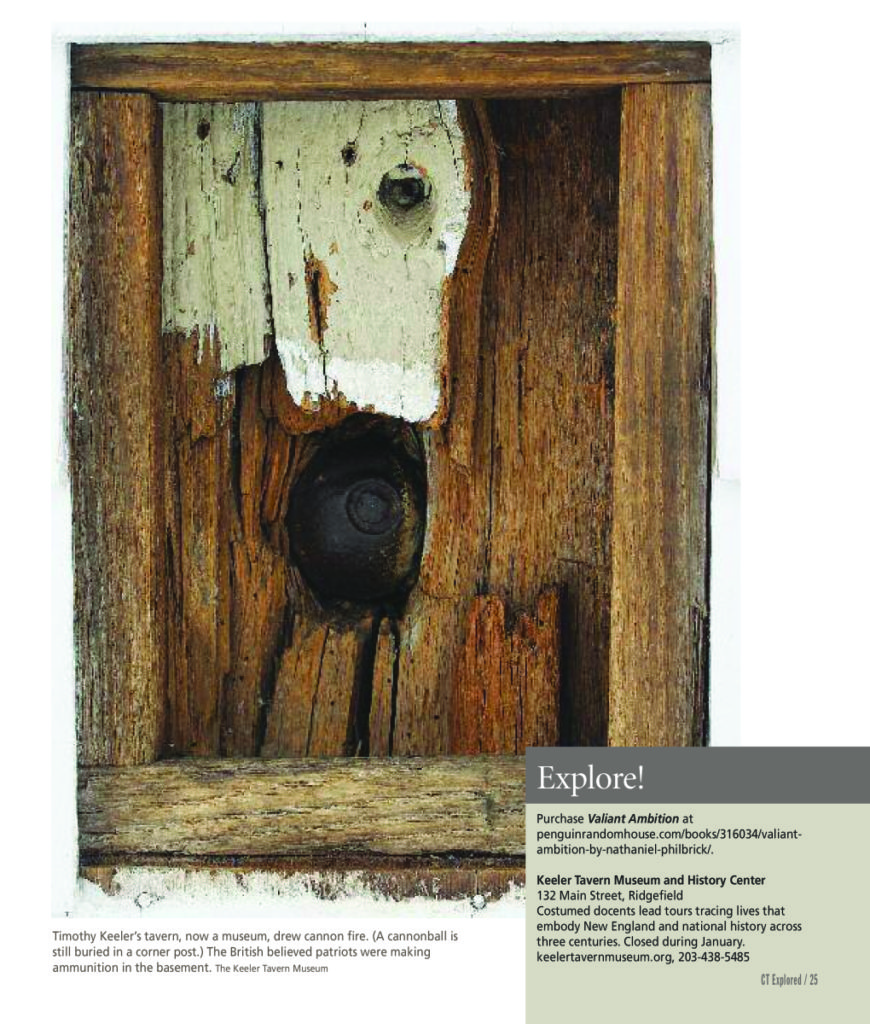

Keeler Tavern Museum and History Center

132 Main Street, Ridgefield

Costumed docents lead tours tracing lives that embody New England and national history across three centuries. Closed during January.

keelertavernmuseum.org, 203-438-5485