By Sharon L. Cohen

As newly trained American soldiers joined the Allies in World War II’s European and Pacific theaters, the United States government turned to the country’s industries to help wage another campaign on the home front. Peacetime plants quickly converted their operations to provide a vast array of military supplies and weapons. President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s message to Congress on January 6, 1941, resonated nationwide: “Powerful enemies must be outfought and outproduced.”

Connecticut was well-equipped to answer his call. Recognized for their expertise in producing high-performance engines, propellers, fighter bombers, and submarines, the state’s manufacturers delivered these well-known products and much more. Hundreds of companies made myriad items for the armed forces, ranging from essential parts such as bearings and springs to innovations in optical and radar systems. According to the March 1, 1946, issue of Connecticut Industry, a journal published by the Manufacturers Association of Connecticut, 175 Connecticut industrial plants received the Army-Navy Excellence in War Production Award (or “E” Award) for “quality and quantity of production based on available facilities.” The article also noted that “Connecticut . . . with its number of awards, stood nearly 100 percent above the average and far above all other states with similar populations.”

Air Force Historical Research Agency, Barrage Balloon Development in the United States Army Air Corp, 1923-1942.

Housed at the state library, the archives of the Connecticut Department of War Records include an unpublished August 15, 1946, report from Naugatuck Footwear Plant detailing its pride in receiving the “E” Award. The plant, a division of the United States Rubber Company, manufactured footwear for all military branches—“approximately 6.5 million canvas shoes, 1.2 million different boot types, 3 million gaiters, and 2 million overshoes over the course of the war.”

The “E” Award also cited Naugatuck Footwear’s contributions beyond its usual product line. When US involvement in the European war appeared imminent, the plant offered the government additional help. Soon, the manufacturer made a completely different defense product: barrage balloons. Photographs from June 6, 1944, provide unmistakable proof of the Connecticut company’s successful completion of this mission. The giant barrage balloons with their long, threatening cables flew high over the beaches of Normandy, France, on D-Day, providing vital protection for the embattled American troops below.

The Rise of Military Ballooning

The road that led Naugatuck Footwear Plant to manufacture barrage balloons started long before World War II. According to F. Stansbury Haydon’s Military Ballooning During the Early Civil War, rev. ed. (John Hopkins Press, 2000), both the Union and the Confederacy used these aircraft for reconnaissance. Barrage balloons were employed similarly in World War I. Even after the invention of the airplane, balloons could be valuable for spotting danger. Before the US entered World War II, the European powers used barrage balloons to prevent artillery bombardment by enemy aircraft.

“The barrage balloon was simply a bag of lighter-than-air gas attached to a cable anchored to the ground,” which could be raised or lowered with a winch, explained US Air Force major Franklin J. Hillson in Airpower Journal 3, no. 2 (Summer 1989). “Its purpose was ingenious: to deny low-level airspace to enemy aircraft,” thus forcing pilots to climb to higher altitudes where precision attacks would be more difficult. Each balloon measured up to 85 feet in length and 35 feet in diameter with a long, swaying piano-wire cable that provided another “mental and material hazard to pilots.” Nighttime—when these wires became difficult, if not impossible, to see—made the balloons even more dangerous, especially when bombs were attached.

Evolving Views on Barrage Balloons

The European Allied Powers in World War I used barrage balloons to keep German bombers from making direct hits on London and surrounding cities. Meanwhile, the American military was much less interested in these weapons, as documented in the formerly classified Army Air Forces Historical Study, no. 3, “Barrage Balloon Development in the United States Army Air Corps, 1923–1942” (December 1943). Indeed, the US military did not consider using barrage balloons until well after World War I.

In 1923, the Army general staff—the officers charged with implementing a division commander’s policies—gave the US Army Air Service (USAAS) responsibility for barrage balloon development. (The predecessor of the US Air Force, the USAAS was the army’s aerial warfare division from 1918 to 1926.) The chief of the Coast Artillery Corps immediately challenged the general staff’s decision since his organization typically oversaw ground defense like antiaircraft artillery. A compromise was reached wherein the USAAS and Artillery Corps would share responsibility for the program. Still, disagreements among the military branches continued for years, with balloon studies and testing occurring only sporadically.

As World War II intensified and the Axis powers employed large-scale use of barrage balloons, the US became more interested in enhanced defense systems. In early 1941, the Air Corps used its research and development funds to conduct additional studies. Several months later, the War Department took steps to implement a complete barrage balloon program, requisitioning a report on the role of the balloons in the war and the capabilities and limitations of the nation’s antiaircraft defense. The Air Corps’s research made it clear balloons “could be made an important auxiliary means of defense.”

The balloons could be used in a variety of additional ways: to defend industrial and military installations, to block navigable routes to central locations, to steer enemy aircraft away from difficult-to-defend areas and toward those offering greater antiaircraft defense, and to deter Axis planes from dropping naval mines by parachute. A detailed plan was developed that included the production of nearly 5,000 barrage balloons and the founding of a new base, Camp Tyson in Tennessee, specifically for balloon battalion training. Approximately 30 battalions were trained there; 4 of these were made up entirely of African American recruits.

The Military Turns to Naugatuck Footwear

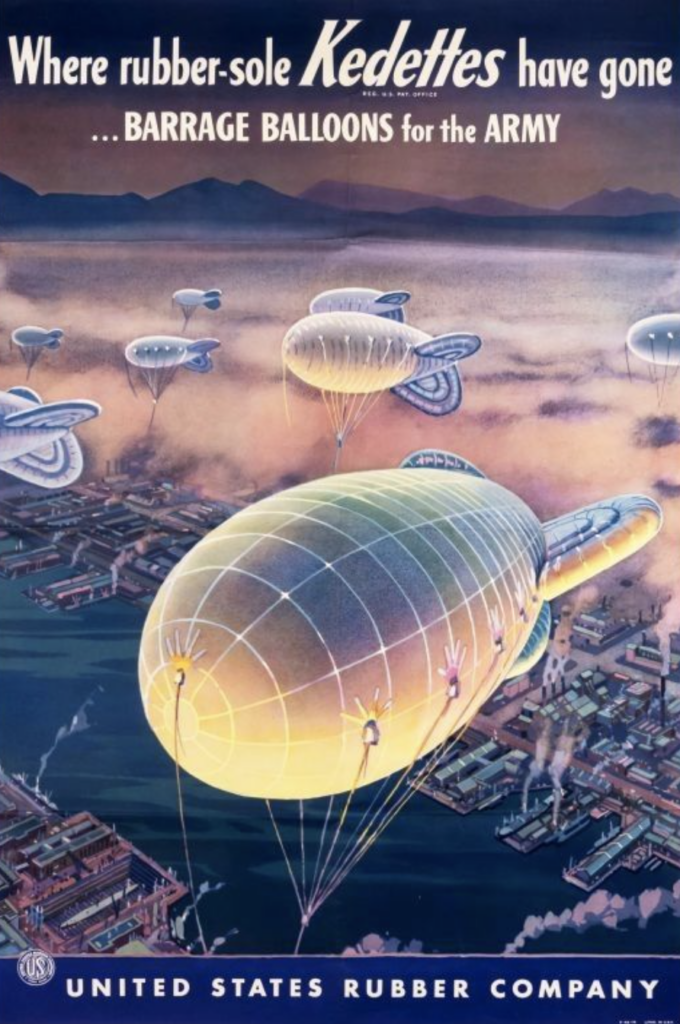

The US government needed a company with a high degree of expertise and experience to help develop and test barrage balloons. The Naugatuck Footwear Plant was the perfect candidate. The report, “Naugatuck Rubber Factories Complex,” offers a valuable overview of the company’s history (Historic American Engineering Record CT-21, May 15, 1985). Established in 1880 by the first licensees of Charles Goodyear’s vulcanizing patent, the company joined nine others to become part of the United States Rubber Company in 1892. Over the years, Naugatuck Footwear introduced several innovative rubber items, including Keds sneakers, which became its flagship product. The company survived the First World War and the Depression and remained one of the largest employers in the region.

During wartime, the military often contracted with companies to manufacture items that fell outside their typical area of expertise, sometimes even those that were being produced for the first time. Such an undertaking could be daunting, especially with the tight deadlines that accompany military requisitions. This was the case with Naugatuck Footwear, which was asked to make barrage balloons instead of the typical consumer items.

The June 21, 1941, issue of The Waterbury Democrat announced that the US Army Air Corps had given US Rubber an “order for the production of barrage balloons.” Several rubber companies nationwide would then produce the balloons based on US Rubber’s prototype. The article explained, “It is commonly agreed among military experts that the barrage balloon has proved strikingly successful in certain defense situations in the current war. Vital targets—such as naval yards, plane factories, and the like—can be well protected against dive-bombing attacks by a protecting ring of barrage balloons trailing their plane-killing cables.”

The footwear plant’s most pressing problem was figuring out how to use synthetic rather than natural rubber, a new challenge for American industry at the time. According to Nyla Provost’s 2022 article, “The Development of Synthetic Rubber and its Significance in WWII” (History in the Making 15, no. 1), it was clear by 1939 that synthetic rubber manufacturing would be essential to US involvement in another world conflict. The majority of American rubber had long come from foreign plantations. This dependence felt increasingly risky, with mounting concerns that Japan would impede access to rubber-producing areas in Asia. In June 1940, President Roosevelt created the Rubber Reserve Company, which would stockpile rubber, promote synthetic alternatives, and designate natural rubber as a strategic material reserved for national security and military applications.

Switching from natural rubber to Thiokol, the new synthetic, presented many operational difficulties for Naugatuck Footwear. More than ordinary rubber, Thiokol—from the Greek words for “sulfur” and “glue”—contained ingredients that helped prevent helium gas from escaping from the barrage balloons. However, as Naugatuck Footwear Plant said in its 1946 report, “The synthetic was more difficult to make, lacked the tackiness of crude rubber, and required numerous dirty and odorous cementing operations that could be toxic. These problems had to be overcome to produce a reliable general-purpose rubber.”

Adapting to synthetic rubber was only one of the challenges the plant faced, the report explained. To develop and produce the balloon prototype in just a few months, Naugatuck Footwear had to purchase different equipment, train employees on new processes and procedures, and expand operations into makeshift manufacturing areas. An entirely new plant in Rhode Island was prepared to help with production once the balloon’s initial development and testing were complete. The prototype was tested at Yale University’s Lapham Field House, and then additional improvements were made. Given that barrage balloons were still unfamiliar in the US at the time—except among those who had served overseas in World War I—one can only imagine the reaction of a person seeing one of these huge balloons floating upward over New Haven for the first time.

Although no American balloons were officially raised before December 7, 1941, the attack on Pearl Harbor prompted immediate action. Concerned about domestic safety, the government established a barrage balloon defense against the Germans on the East Coast and the Japanese on the West. Balloons soon appeared in Norfolk, Pensacola, and New York; over San Francisco, Los Angeles, and Seattle; and near vital facilities in the Great Lakes, Hawaii, Puerto Rico, and Panama.

American Barrage Balloons See Action

Camp Tyson began balloon battalion training in 1941. Arriving at the base and seeing the balloons for the first time, the recruits did not know what to think. The enormous floating aircraft were not crewed like blimps, nor did they have cockpits. According to Shannon McFarlin in Camp Tyson (Arcadia, 2017), the soldiers called them “flying elephants,” as well as “gas bags” and “flying bombs.”

The battalions headed across the Atlantic to raise their balloons and protect the most vulnerable locations. They shielded several ports in the North African campaign that lacked sufficient air defenses. In August 1943, 60 balloons were sent to Oran, Algeria, to discourage enemy torpedo- and dive-bombing and prevent low-level aircraft attacks. When the Allied troops captured the port of Naples, Italy, the balloons defended this vital harbor from enemy aircraft despite its proximity to German lines.

In Forgotten: The Untold Story of D-Day’s Black Heroes, at Home and at War (Harper, 2015), Linda Hervieux details the Allied invasion of Normandy, one of the most notable events that involved barrage balloons and bombs during World War II. On June 6, 1944, the 320th Barrage Balloon Battalion, one of the balloon units made up entirely of African American troops, tried to protect US infantry and armor as they labored across Omaha Beach under constant fire. Although numerous balloons never made it to shore, the men of the 320th were able to float a dozen balloons over the Allied fleet before nightfall. “If a Nazi bird nestles in my lines, he won’t nestle nowhere else,” declared one soldier, as quoted in Matthew F. Delmont’s Half American: The Epic Story of African Americans Fighting World War II at Home and Abroad (Viking, 2022).

Behind an American flag, a convoy of landing craft head for Utah Beach on June 6, 1944. Each ship has barrage balloon connected by a cable during the D-Day invasion

Eventually, about 140 US balloons guarded Omaha and Utah Beaches. Fulfilling their primary purpose, the balloons forced German planes to higher altitudes, where they became easy targets for Allied pilots’ antiaircraft guns. According to Hervieux, the success of the 320th, the only unit to float balloons during their 140 days in France, brought them national and even international recognition, including from Supreme Allied Commander Dwight D. Eisenhower, who commended the battalion for conducting “its mission with courage and determination” and called it “an important element in the air defense team.”

During the war, barrage balloons destroyed 24 piloted enemy aircraft and stopped over 230 unpiloted enemy missiles. Although many US aircraft also crashed when colliding with the balloon cables, the military agreed that the deterrent value of the barrage balloon was incalculable. In his Airpower article, Major Hillson affirmed the importance of these balloons: “The balloons are gone, but the low-level threat still poses a problem. The barrage balloon can still provide effective, force-enhancing protection against this form of attack. Because of their point defense capability, barrage balloons are ideally suited for air base defense.”

Naugatuck Footwear Receives Praise

“Where rubber-sole Kedettes have gone…Barrage Balloons,” a poster produced by the US Rubber Co., 1943.

On December 29, 1943, employees and numerous town residents attended the Army-Navy “E” Award ceremony at Naugatuck Footwear Plant, including several well-wishers from the armed forces and state government: Private John F. Bartek, who had drifted for 21 days in the Pacific Ocean with World War I Medal of Honor recipient Captain Edward V. Rickenbacker after the plane they were on crashed into the sea; Connecticut Governor Raymond E. Baldwin; and Technical Sergeant Joseph G. Marcelonis, a former plant employee who had just returned after completing 25 successful bombing missions over Europe.

The Naugatuck Footwear Plant joined Connecticut companies of all sizes and in all counties to provide much-needed support for the Allied cause during the Second World War. Its work on the barrage balloons helped advance the use of synthetic rubber, which revolutionized the rubber industry. As the company’s postwar report put it, “‘Now It Can Be Told’ could be the title to this story describing the tremendous effort in many varied fields of war production that Naugatuck Footwear Plant made as its contribution toward the war’s successful conclusion.”

Sharon L. Cohen is a Newtown communications specialist and author. Under her High Point Publishing LLC, she recently published the book Connecticut Industries Unite for WWII Victory.

Learn More!

Raechel Guest, “The Brass City Manufactures for Victory,” Connecticut Explored, Fall 2007, ctexplored.org/the-brass-city-manufactures-for-victory

Thomas Paone, “Protecting the Beaches with Balloons: D-Day and the 320th Barrage Balloon Battalion,” National Air and Space Museum, Smithsonian Institution, June 4, 2019, airandspace.si.edu/stories/editorial/protecting-beaches-balloons-d-day-and-320th-barrage-balloon-battalion