(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Spring 2016

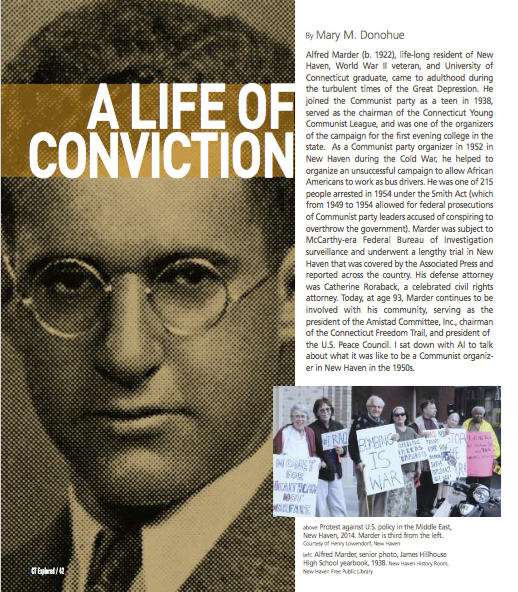

Alfred Marder (b. 1922), life-long resident of New Haven, World War II veteran, and University of Connecticut graduate, came to adulthood during the turbulent times of the Great Depression. He joined the Communist party as a teen in 1938, served as the chairman of the Connecticut Young Communist League, and was one of the organizers of the campaign for the first evening college in the state. As a Communist party organizer in 1952 in New Haven during the Cold War, he helped to organize an unsuccessful campaign to allow African Americans to work as bus drivers. He was one of 215 people arrested in 1954 under the Smith Act (which from 1949 to 1954 allowed for federal prosecutions of Communist party leaders accused of conspiring to overthrow the government). Marder was subject to McCarthy-era Federal Bureau of Investigation surveillance and underwent a lengthy trial in New Haven that was covered by the Associated Press and reported across the country. His defense attorney was Catherine Roraback, a celebrated civil rights attorney. Today, at age 93, Marder continues to be involved with his community, serving as the president of the Amistad Committee, Inc., chairman of the Connecticut Freedom Trail, and president of the U.S. Peace Council. I sat down with Al to talk about what it was like to be a Communist organizer in New Haven in the 1950s.

MD: Al, you grew up in New Haven during the Great Depression. What was that like?

AM: My parents were Jewish immigrants from the Ukraine. They owned a small grocery store during the 1930s on Oak Street. We worked and ate in the store. It wasn’t far from the railroad yards and on a daily basis men would come into the store and ask for food. I sometimes gave them food, but my father would say, “We cannot afford to feed the whole world.” Life for my parents was hard. The sheriff would come into the store and demand money out of the register to pay creditors.

MD: What were the major influences on you when you were growing up?

AM: I went to James Hillhouse High School in New Haven with many children of immigrants with socialist ideas. We were deeply concerned about the rise of fascism in Spain and knew men that volunteered for the Abraham Lincoln Brigade [Americans who fought as volunteers in the Spanish Civil War, 1936 – 1939]. Discussions about labor rights, unionization, racial equality, and the American economy were common. The Hillhouse Debate Team topic one year was “Is the U.S. Post Office Socialist?” People came from families that were hungry. There was no denying that working people were suffering.

MD: How did you become politically active?

AM: I became active in high school organizing New Haven workers in unions—electrical, steel, and clothing workers. Union organizers were young people, too, and they needed volunteers, so I helped to distribute flyers. We lived on Davenport Avenue in a two-family house. I slept on a porch so it was easy for me to get dressed and sneak out of the house to go hand out flyers before the 7 a.m. work shift at Sargent’s and New Haven Clock companies. The organizer would pick me up—I’d go out the window. I would come home, go back to bed, and pretend to wake up when my mother called me. I discovered much later that my parents knew what I was doing but decided not to stop me.

MD: What happened after high school?

AM: I stayed out [of school]one year and did youth work. I was the chairman of the New Haven Conference of Youth and helped to organize the campaign for the first evening college in Connecticut at what’s now Southern Connecticut State University. There were no college courses available for working kids. We recruited students for the night college—everyone involved in the campaign had to enroll. After one semester I transferred to UCONN. I was drafted into the U.S. Army in 1942 and for almost two years, the army wouldn’t send me overseas because of my political views as a Communist.

MD: What about the Cold War period of the 1950s? I found your name in more than 50 newspaper stories from across the country.

AM: I become a printer to support my family and was a Communist party (CP) organizer. It was a violent period. My phone was tapped, my neighbors were interviewed by the FBI, my mail opened. This was the McCarthy period. Conditions became such that the CP couldn’t afford staff. In 1952, we thought communists would be rounded up and arrested, so I went to New York City under an assumed name, “Ken Green,” and got a printing job. I was arrested on May 29, 1954 at my home in New Haven as a communist leader and indicted by a federal jury for violation of the Smith Act. There were seven of us arrested [later an eighth was added], and we plead[ed]innocent. We couldn’t get legal representation. No one wanted to be associated with communists. So I sent a mimeographed letter to hundreds of Connecticut attorneys asking for representation. We maintained that being a member of the CP was not illegal. Six of the defendants were convicted and I was acquitted, but their sentences [were]later thrown out by a federal appeals court. [They] found no direct evidence that showed that the defendants advocated the violent overthrow of the government. [Still,] this frightened people and decimated the CP.

MD: And since the 1950s?

AM: In the 1970s, I worked against the [Vietnam] War; 1980s on the anti-nukes movement, the first world conference for peace in 1986; the founding of the Amistad Committee in 1988. I continue to be involved in the struggle for workers’ rights, racial equality, and peace.

Mary M. Donohue is a frequent contributor to and the assistant publisher of Connecticut Explored. She thanks Al Marder for granting this interview, conducted in August 2015.

SUBSCRIBE!

EXPLORE!

Conversation with Al Marder and Judge Andrew Roraback

April 14, 2016, 5:30 p.m.

New Haven Museum, 114 Whitney Avenue, New Haven. Free

Hear longtime community activist Al Marder talk about his early days in New Haven as a labor organizer and communist party member and his arrest at his home under the Smith Act in 1954. Judge Andrew Roraback will share insights about Marder’s defense by Roraback’s cousin, the celebrated Catherine Roraback. newhavenmuseum.org

READ

For more information about the labor movements including the Communist Party in the 1930s, read Hartford Labor Militants Fight the Spanish Civil War Connecticut Explored, Summer 2004, ctexplored.org/hartford-labor-militants-fight-the-spanish-civil-war/

RESEARCH

To access more than 50 newspaper articles pertaining to the New Haven Smith Trials and Alfred Marder visit Ancestry.com and search for Alfred Marder.