By Katherine Hermes

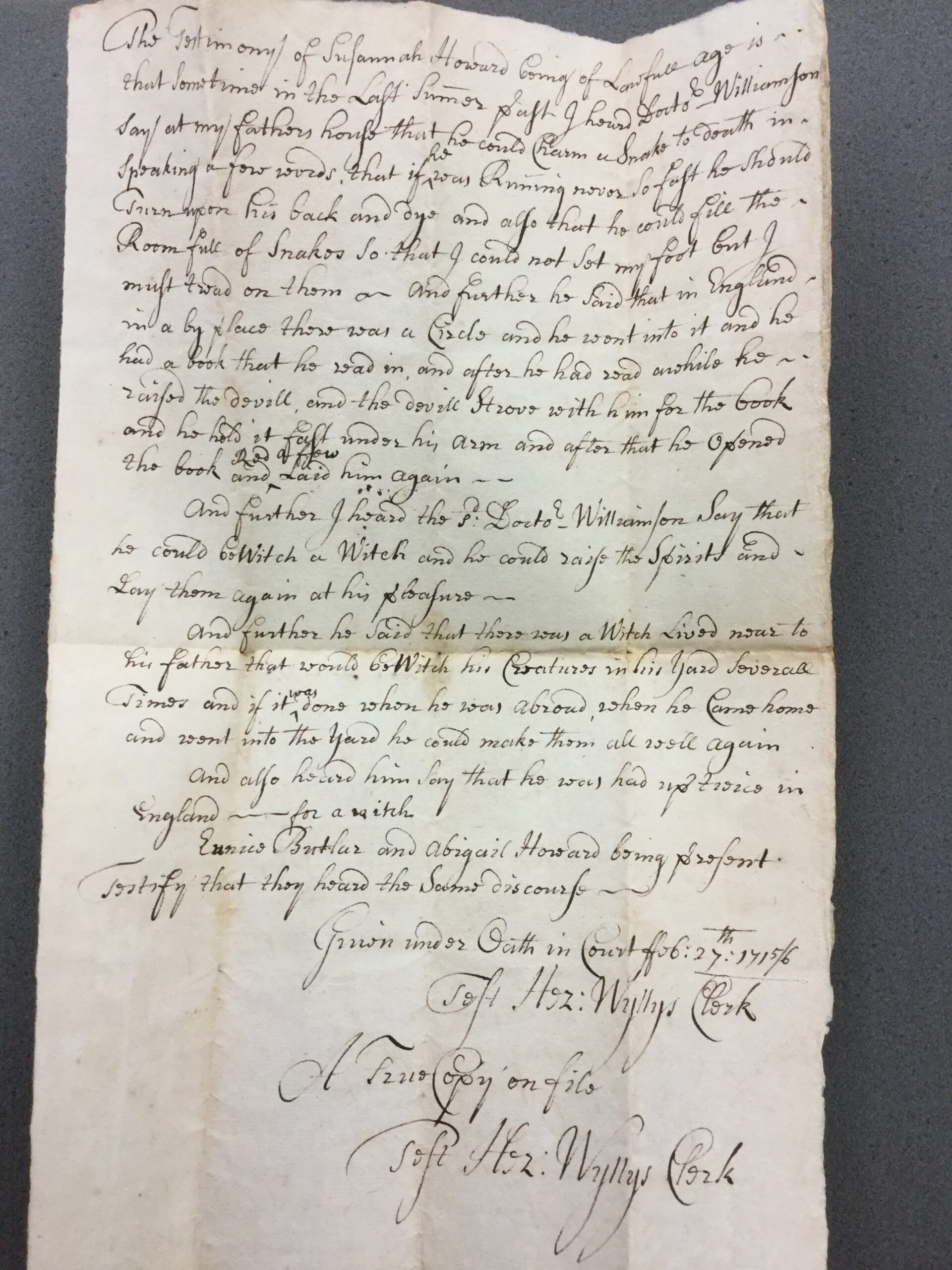

On February 27, 1715/1716* Samuel Howard’s 16-year-old daughter Susannah gave sworn testimony in court about a conversation she had had with Dr. Alexander Williamson in the presence of her sister Abigail and their friend Eunice Butler. “Sometime in the last summer past I heard Doctor Williamson say at my father’s house that he could charm a snake to death in speaking a few words,” Susannah testified. “And further he said that in England in a by-place there was a circle and he went into it, and he had a book that he read in, and after he had read awhile he raised the devil and the devil strove [fought]with him for the book, and he held it fast under his arm, and after that he opened the book and read.…”

After Williamson recounted struggling with the devil for the book, Susannah said, he told her “he could bewitch a witch and he could raise the spirits and lay them [down]again at his pleasure.” Williamson bragged that “there was a witch lived near to his father that would bewitch his creatures in his yard several times and if it was done when he was abroad, when he Came home and went into the yard he could make them all well again.” Then, she alleged, he told her the most frightening thing of all, that he had been charged twice in England with witchcraft. The clerk of the court, Hezekiah Wyllys, dutifully wrote down Susannah’s testimony.

The transcript of her testimony reveals that two decades after the last trial of an accused witch and more than 50 years after the last executions for witchcraft in Connecticut, there were still local people who believed in witchcraft. Assuming Susannah’s testimony was accurate, its transcript is the first document in Connecticut that demonstrates an admission to practicing witchcraft that was not coerced or produced under duress. Unlike the women and men who were prosecuted for witchcraft in New Haven and Connecticut colony courts in the 17th century, Williamson appears to have been goading the girls with his words, not confessing to a crime. He said he read a book to the devil, not that he signed the devil’s book, but he was still invoking commonly held images of the witch-devil relationship. He must have had no fear of prosecution.

Twenty-four years earlier the words of teenage girls had produced witchcraft panics in Salem, Massachusetts, and Fairfield, Connecticut, but in 1715/16 the claims of Susannah and two adolescent witnesses were largely ignored.

Witchcraft

Hezekiah Wyllys was the Connecticut Colony’s secretary from 1712 to 1734. His father, Samuel Wyllys, whose papers are in the Connecticut Archives at the Connecticut State Library (CSL), have significant information about witchcraft. The deposition Susannah gave, however, was not with the other papers on the subject of witchcraft. It was catalogued at CSL with the general case files for the County Court, Hartford County. According to John Putnam Demos in his comprehensive work Entertaining Satan (Oxford University Press, 1982), after 1692 there were “no more executions, no convictions, indeed no actual indictments” for witchcraft in New England courts. R. G. Tomlinson’s Witchcraft Trials of Connecticut (The Bond Press, 1978) cites a letter to The Hartford Times on October 15, 1819 alleging there was a Connecticut witchcraft trial in 1696 that resulted in the burning of the accused, a detail that had to be false because no accused witches were burned in New England. The case was probably that of Wallingford’s Winifred Benham and her daughter, the last people tried for witchcraft in Connecticut in September and October 1697, the documents of which were compiled by Charles Bancroft Gillespie in An Historic Record and Pictorial Description of the Town of Meriden (Journal Publishing Company, 1906). While gossip and tales about witches continued, none about Doctor Williamson or Susannah Howard’s allegations survives in written form.

According to Wallace Notestein in A History of Witchcraft in England from 1558 to 1718 (American Historical Association, 1909), there were other purported witch-physicians in England, and some spent time in prison. Williamson’s assertion that he was brought up on charges twice in England is thus not outlandish on its face. More often, though, physicians played the opposite role in witchcraft cases. Norman Gevitz in “‘The Devil Hath Laughed at the Physicians’: Witchcraft and Medical Practice in Seventeenth-Century New England” (Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences 55, no. 1, 2000) identified the names of 46 medical practitioners—doctors, surgeons, and pharmacists—who appear in New England records. These professionals served on juries and coroners’ inquests or offered testimony against the accused.

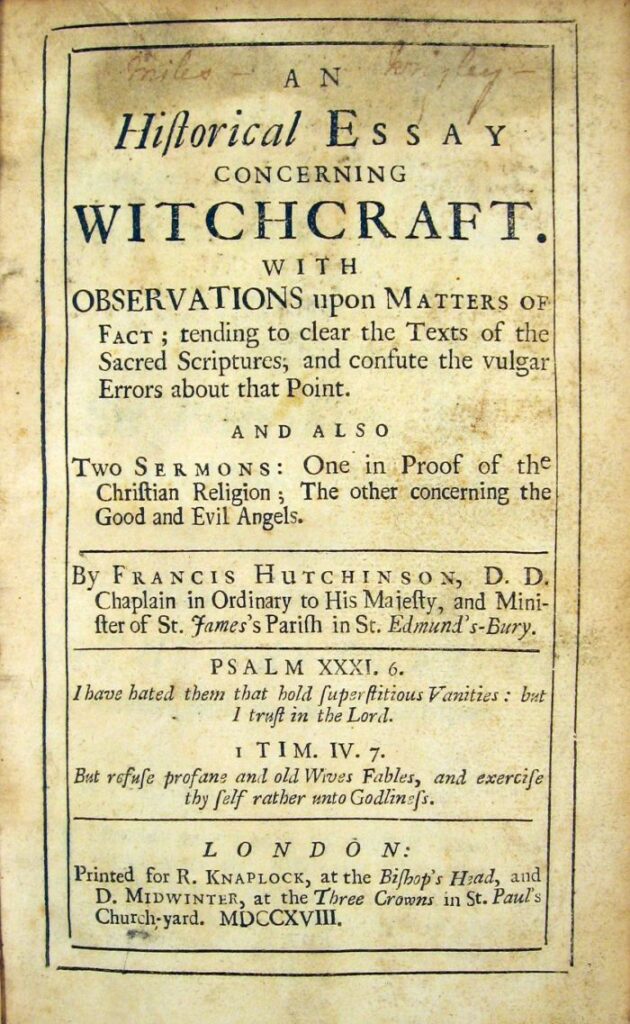

Although New Englanders may have been both wary and weary of witchcraft accusations by 1716, the criminalization of witchcraft was by no means dead in the Anglo-American world. Francis Hutchinson’s essay “An Historical Essay Concerning Witchcraft” published in London by R. Knaplock in 1720 urged reform and an end to witchcraft prosecutions. England’s legislation to end the prosecution of witchcraft came with the Witchcraft Act of 1735, two decades after Susannah Howard told her story in court. As Marion Gibson showed in Witchcraft and Society in England and America, 1550-1750 (Cornell University Press, 2003), the 1735 English law made it a crime for a person to claim that another person had magical powers or was guilty of practicing witchcraft. The only prosecutions under the law were of people who claimed to be sorcerers or conjurers, thereby committing a kind of fraud.

Susannah Howard was born in 1699. At 16, she was able to testify under oath, but her younger sister, Abigail, was not of lawful age and could only affirm what Susannah said. Church records show Eunice Butler was admitted to communion in the Congregational church in March 1716. They were young and perhaps impressionable girls. But why would Susannah tell a court a witchcraft story about Dr. Williamson?

The Lawsuit Against Howard

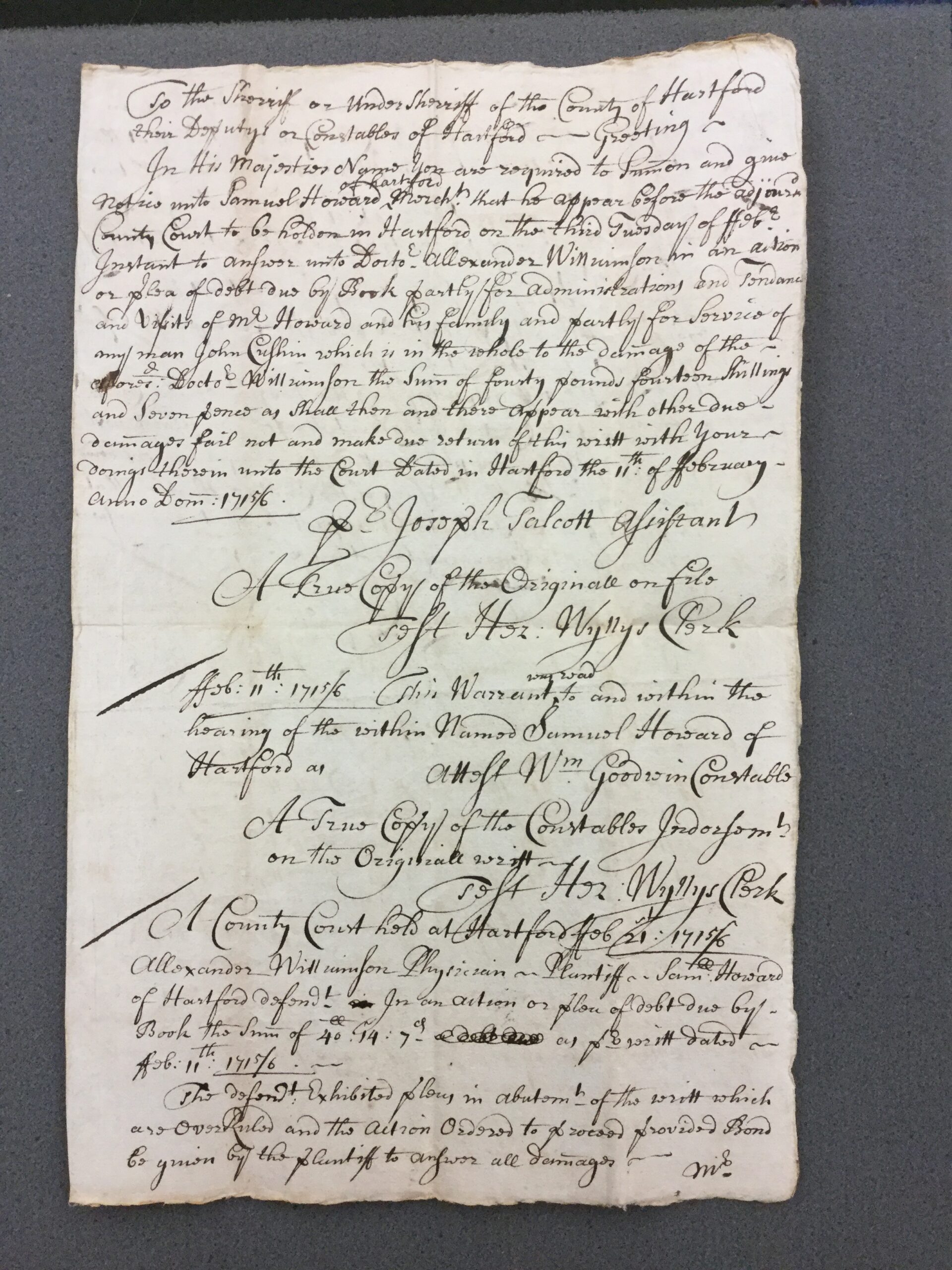

Samuel Howard was a very sick man when the sheriff came to his home to serve him with a summons on February 11, 1715/16. For the past eight months Dr. Alexander Williamson had made numerous house calls and prescribed and prepared elaborate treatments to address Howard’s symptoms, which included coughing, chest pain, difficulty breathing, and constipation. Howard’s medical bills amounted to £40=s14=d7, or nearly $12,000 in today’s money. Howardwas a successful merchant and 52 years old when his summons was served. He lived in Wethersfield with his wife, also named Susannah, and their children. Ten days after the issuance of the summons, the suit of Dr. Alexander Williamson against Samuel Howard, an action of a debt due by book, was heard in the Hartford County court. Howard challenged the doctor’s complaint, but the court denied the challenge and ordered the case to proceed. Williamson was represented by John Read, the Queen’s attorney acting in a private capacity. Howard’s attorney conceded that Howard owed £17 (about $5,200 today), but “for the Rest puts himself upon the Country In this action.” The jury found for Howard, and Williamson gave notice of appeal. The court warned Williamson that if he could not “make his plea good” he would owe Howard 19 shillings in court costs.

On February 25, 1715/16 Samuel Howard made out his will. He named his wife and his son as joint executors. About two days later, he died. He left a sizable estate of £2205 (or about $678,000.00 today).

The Doctor in the House

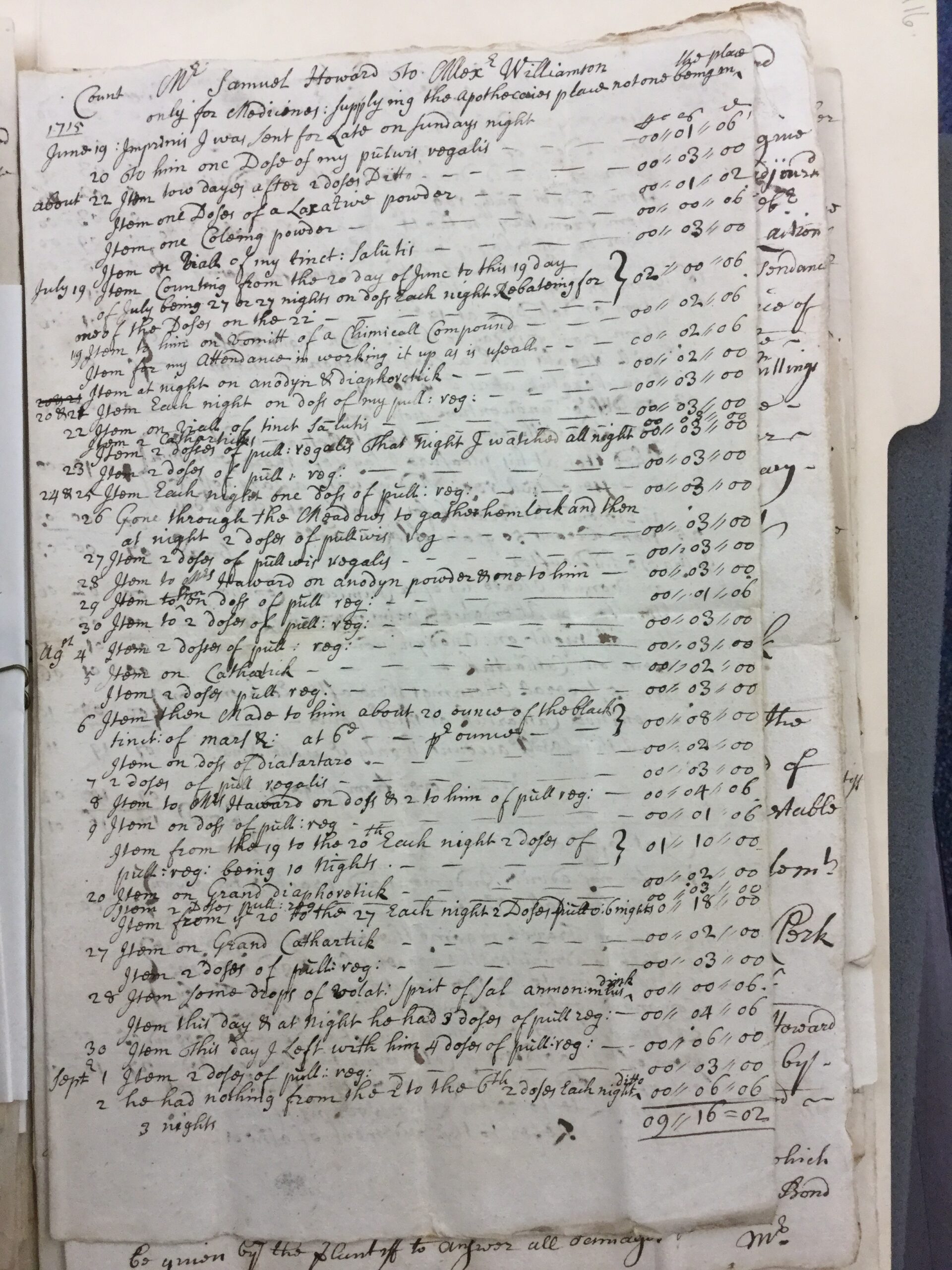

Dr. Williamson was new to the Hartford area when he began treating Samuel Howard, and he was sometimesdescribed in court documents as being from New York. His statements to Susannah Howard as recorded in her testimony indicate he came from England. He was not without friends in high places, such as attorney Read. Williamson also treated Jonathan Bunce, Howard’s brother-in-law and a well-known tavern owner, whom he also later sued. Little else is known about him. His treatments of Howard, though expensive, appear consistent with the types of medicines prescribed by other doctors. A typical entry from copies of Williamson’s account books submitted to the court included charges like these:

June 19 : Imprdnis I was sent for Late on Sunday night £ s d

20 To him onc Dose of any putuis vegalis _ __ __ __ 00=01=06

about 22 Item Tpw dayes of after 2 doses Ditto _ __ __ __ 00=03=00

The documents in the lawsuit show that between June 1715 and February 1715/16 Williamson prescribed laxative treatments, anodyne powders (painkillers), and purges. At one point he visited Howard five mornings in a row. He mixed a chemical compound to make Howard vomit, and then made up a “Cathartick” to settle him down. He used a diaphoretic antimony, probably made with a semi-metal ore obtained in northeast England as was the common practice, to make Howard sweat. According to R. I. McCallum in “Observations upon Antimony” (Proceedings of the Society of Medicine70, November 1977), alchemists believed antimony “healed wounds rapidly; cured leprosy and the French Disease; purified the blood, dispelled melancholy, relieved chest pain and breathlessness,” among other things. The antimony treatment alone cost Howard more than £4.

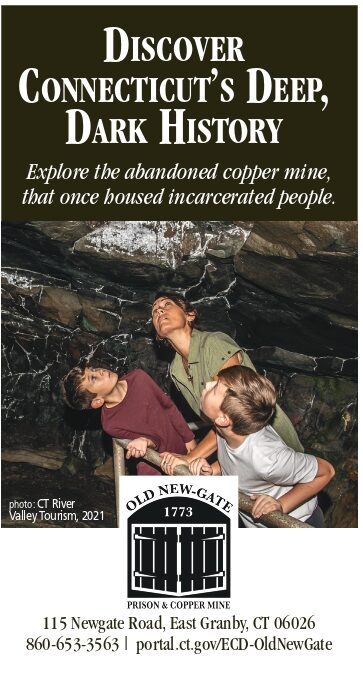

Dr. Williamson’s complaint against Samuel Howard lists the costs and nature of Howard’s

medical treatment, 1715/16 photo: Katherine Hermes, courtesy of the Connecticut State Library

Susannah watched her father waste away. She also watched the doctor come and go on a regular basis with no improvement in her father’s health. No one can know the exact motivation behind her testimonial statement or what she wished to happen after she gave it, because there is no evidence beyond her recorded court testimony. The convergence of circumstances—a failed healer, a torturous death, and a legal fight over money—were not unusual in accusations of witchcraft, as demonstrated in Carol Karlsen’s study The Devil in the Shape of a Woman (W.W. Norton, 1998). Susannah’s testimony was different from many in that she did not accuse Williamson of bewitching her father, but multiple studies of witchcraft cases like those documented by Karlsen and Demos show revenge or frustration in legal disputes were common motives. Such a motive does not mean Susannah did not give truthful testimony or that she did not believe Williamson was in league with the devil. If she stopped short of accusing the doctor of causing her father’s death by witchcraft, it could have been simply because by 1716 the court was unwilling to allow it.

Alexander Williamson died in November 1716. His time in Connecticut probably amounted to less than two years. His probate documents in Connecticut list him as being from New York, and John Read’s bond for the administration of his property in Hartford is the only document related to his estate. There is no death record, burial information, will, or inventory. He is not recorded in the classic histories of the period, James Hammond Trumbull’s Memorial History of Hartford County, Connecticut, 1633-1884 (Edward L. Osgood, 1886) or William Deloss Love’s The Colonial History of Hartford (self-published, 1914). Were it not for a lawsuit he brought to recover an unpaid debt, Dr. Alexander Williamson’s fleeting career in Connecticut would never have been known. And were it not for Susannah Howard’s testimony, filed away in the archives, we would have no idea that there was perhaps much more to Dr. Williamson than his prosaic action to collect a debt.

Katherine Hermes is the publisher of Connecticut Explored. she is the author with Beth Caruso of “Between God and Satan: Thomas Thornton, Witch-Hunting, and Religious Mission in the English Atlantic World, 1647–1693.” Connecticut History Review 61, no. 2 (2022): 42-82.

Frontispiece of Francis Hutchinson, An Historical Essay Concerning Witchcraft. photo: Wikimedia Commons

Sheriff’s writ of summons for the appearance of Samuel Howard, 1715/1716 photo: Katherine Hermes, courtesy of the Connecticut State Library

Read More!

“Accused! Fairfield’s Witchcraft Trials,” (excerpts from the graphic novel by Jacob Crane),

Connecticut Explored, Fall 2016

Chris Pagliuco, “Wethersfield’s Witch Trials,” Hog River Journal, Winter 2007/2008

“Witchcraft in Connecticut,” CT Humanities, connecticuthistory.org/witchcraft-in-connecticut/

Explore!

Connecticut Colony Seventeenth-Century Witch Panic, Ancient Burying Ground, Hartford, ancientburyingground.com/pioneers/witchcraft-trials/