(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Fall 2020

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

This year marks the 75th anniversary of the end of World War II. Liberation of Europe was a gradual process, starting with the Soviet victory at Stalingrad in 1943 and the Normandy invasion in 1944. This pincer action, with the Soviets coming from the east and the Allies from the west, culminated in the unconditional German surrender to the Allies on May 8, 1945. The Soviets insisted on a separate surrender, and the Germans acceded to this on May 9, resulting in a one-day difference between the two celebrations of VE (European Victory) Day.

That day stands out in my memory as if it were yesterday. I was just shy of 10 years of age but didn’t know it then since, as a Jewish child, I had gone into hiding when I was 7, leaving home without knowing the date or the year of my birth.

I was living in the city of Lvov (the Russian name for the Polish city of Lwów, now the Ukrainian city of Lviv) with a wonderful Jewish woman, Mrs. Tola Wasserman, who had lost her entire family and survived the war in hiding. She and I lived in an apartment considered rather large by the Soviet authorities, so they billeted several wounded veterans with us. As I recall, there were four, each with a missing limb, or part of a limb, separated from their families with many war experiences behind them. When they heard rumors of the end of the European war, they bought several bottles of vodka to properly celebrate the event. Mother Tola (as I called her) would have none of it. She confiscated the bottles but promised that if they were correct, she would buy them two additional bottles and join them in the celebration.

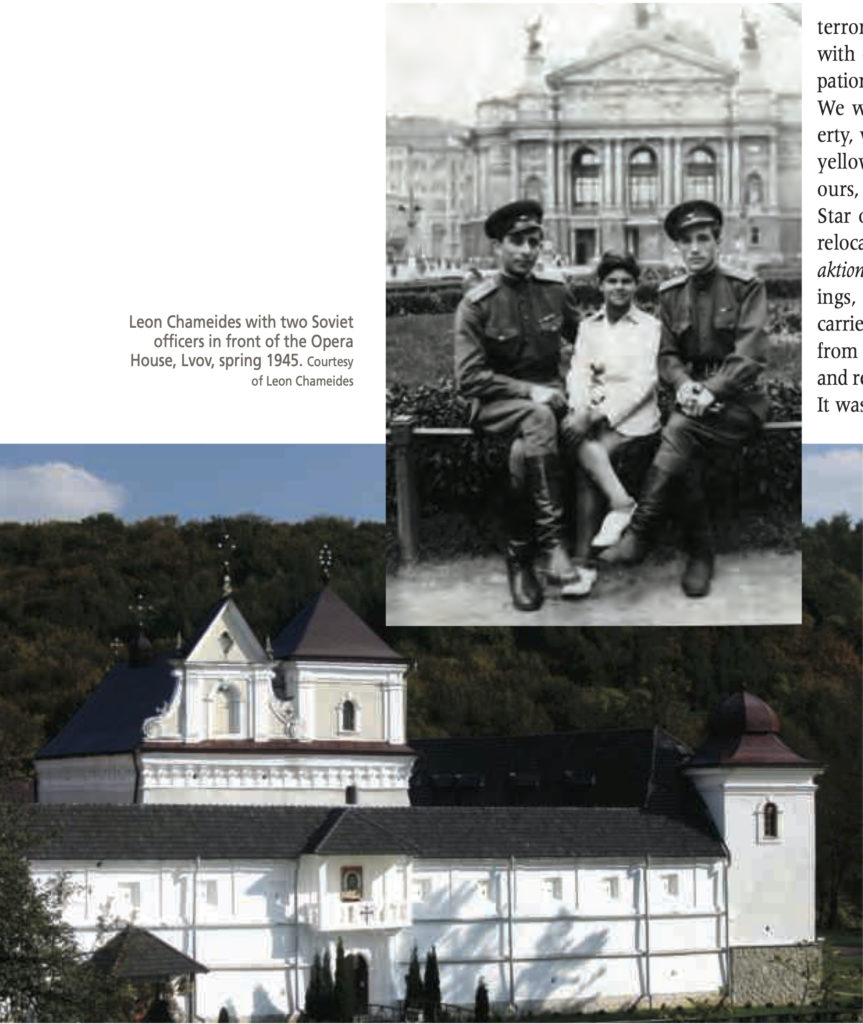

The next day, a loudspeaker from a passing truck (no one had a radio) informed us that “batko” (Father) Stalin would make an important announcement the next day. The following day, people gathered in front of the beautiful opera house, full of anticipation. There was an almost palpable excitement in the air. A hush fell on the crowd the moment a voice came from the loudspeaker and announced that the European war had ended. There was a sudden eruption of happy jubilation and cheering. Strangers hugged and kissed. Someone started playing an accordion, and people began singing popular Russian songs and dancing. Mother Tola returned the bottles of vodka, plus two, to our housemates, who immediately shared their bounty. Our hearts were full of joy, and yet….

Our joy was muted; we had difficulty in grasping and dealing with the enormity of our loss. I suspect that everyone in that square lost someone, but we had lost almost everyone. As Holocaust survivor, teacher, and writer Elie Wiesel was to say later, “Not all victims were Jews, but all Jews were victims.”

In 1939 Lwów had a total population of approximately 312,000. About 50 percent of the population were Poles, 32 per cent (approximately 100,000) were Jews, and 16 percent were Ukrainians. The Jewish population grew significantly (to between 119,000 and 150,000) with the arrival of many refugees after the division of Poland between Germany and the Soviet Union as agreed to in a secret addendum to the German-Russian non-aggression pact of August 23, 1939. My family was part of this migration. I was born in Katowice in southeastern Poland, where my father had been the town rabbi since 1929. Just days before the start of the war, which began on September 1, 1939, we fled Katowice by train 250 miles east to Lwów to join my paternal grandparents, aunts, uncles, and cousins. Katowice would soon become part of Nazi Germany and Lwów would soon become part of the U.S.S.R.

Now we were celebrating the end of this brutal war, but by the time of liberation, only 823 of the Lwów’s Jews remained alive, and my brother and I were the only survivors in our family. The victims included my parents, my paternal grandparents and their siblings, my uncles Ajzyk, Berel, and Elias, my aunts Rivka and Tziporah, and many cousins. Many years later I researched and wrote a family history, Strangers in Many Lands: The Story of a Jewish Family in Turbulent Times (self-published, 2012) in which I identified the names of 60 family members who I definitely knew were victims. My brother and I survived thanks to our parents’ foresight and courage to separate from their two children, ages seven and nine, and to Metropolitan Andrey Sheptytski and the Studite Brothers of the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church who, at risk to their own lives, had the moral courage to answer the Biblical question, “Am I my brother’s keeper?” in the affirmative.

The Germans attacked the Soviet Union on June 21, 1941 and entered Lemberg (Lwów’s German name) on July 1. The anti-Jewish campaign of terror started almost immediately, with either passive or active participation of our non-Jewish neighbors. We were forced to surrender property, wear an identification sign (the yellow star in some sections but, in ours, a white armband with a blue Star of David) and were eventually relocated to a locked ghetto. Periodic aktions(operations resulting in beatings, arrest, and murder) were carried out. The worst of these lasted from August 10 to August 29, 1942 and resulted in 50,000 Jewish deaths. It was, I believe, this event that convinced my parents that no Jew would be spared. Young children were especially vulnerable because their labor could not be exploited. We now know that 1.5 million children were murdered and that the chance of survival for Jewish children in Poland during those years was less than 0.5 percent.

On August 14, 1942 my father, as a representative of the Jewish community, met with Metropolitan Andrey Sheptytski, the head of the Uniate or Greek Catholic Church, to see if he would be willing to hide 600 Torah scrolls. The Uniate Church was established in 1596 as a union of the Eastern Orthodox and the Roman Catholic traditions. The Church recognized the authority of the Pope and was allowed to continue using Orthodox rituals and practices. Andrey Sheptytski was installed as Archbishop and Metropolitan in 1900 and over the years was known for numerous acts of friendship toward Jews. He agreed to hide my brother and me, and in Fall 1942 my father brought me to the Archbishop’s residence. I was then separated from my brother, who would live with 12 different Ukrainian families.

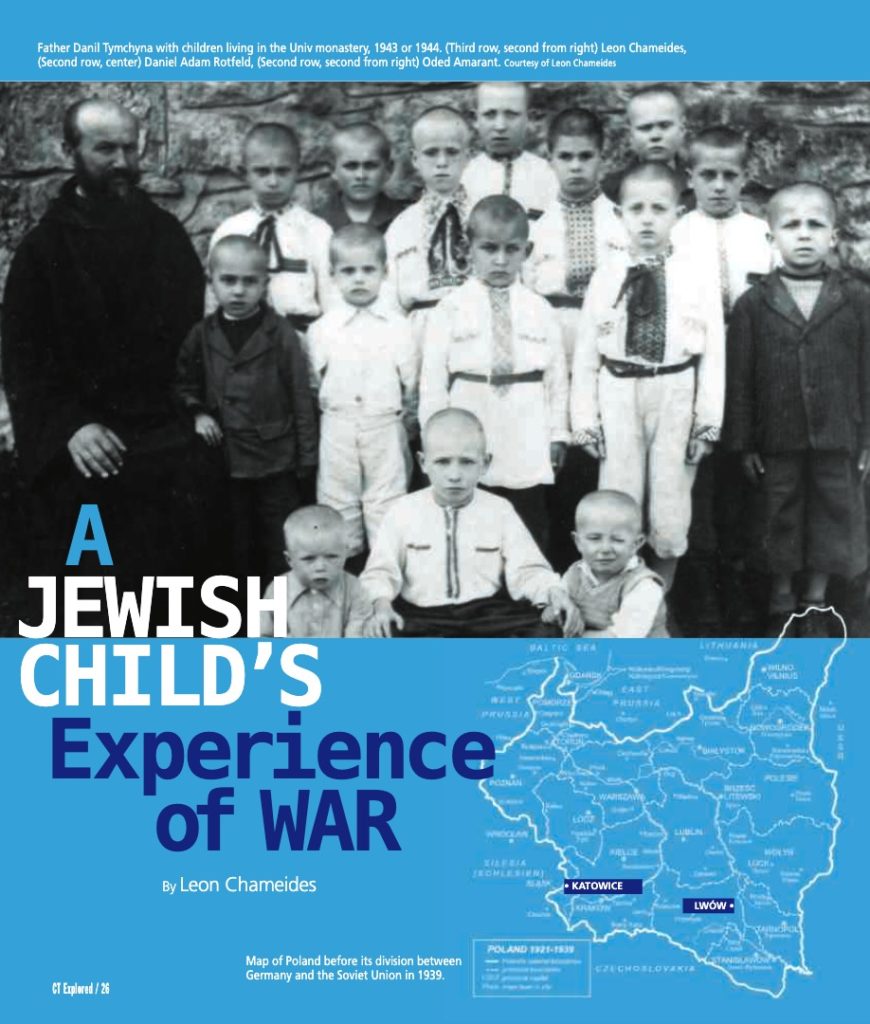

I spent the next two years in the orphanage of the monastery in the village of Univ near Peremyshliany (Przemyślany in Polish) pretending to be a Ukrainian. To carry this out successfully, I had to learn Ukrainian (my native languages were German with my parents and Polish with our nanny and cook), to answer to a new name (Levko Chaminskyi), to know the elements of the Greek Catholic ritual and prayers, never to speak about my past, and never to take a bath or go to the bathroom in anyone’s presence because I was circumcised, while Christian boys there at the time were not. The monastery was almost self-sufficient in food, and we took part in farm chores. We attended the village school taught by Mr. Dyuk. There were two other Jewish children in the monastery and, unknown to us, Mr. Dyuk was hiding a family of four, including a little boy, in the school attic. In the 1990s I finally succeeded in identifying and meeting the other children hidden there.

top: Leon Chameides with two Soviet officers in front of the Opera House, Lvov, spring 1945.; bottom: The Monastery of the Uniate Greek Catholic Church in Univ, Ukraine, 2007. Courtesy of Leon Chameides

The battle front finally came to us as the Soviet forces fought their way westward and we were liberated in July 1944. Unfortunately, our troubles did not end. The Soviets began arresting and deporting many of the priests and eventually banned the Uniate Church, which was only resurrected with Ukrainian independence in 1991. Tragically, many of the priests who saved me became victims in the Soviet Gulag, including Clement Sheptytski (the Metropolitan’s brother), who is said to have died in the same prison that housed Raoul Wallenberg, the Swedish diplomat who saved tens of thousands of Jews from Nazi extermination in 1944 and 1945.

I was able to leave Univ on a horse-drawn carriage going to the Archbishop’s residence. It was there, in the chapel during morning Mass, that I looked up and saw my brother. He motioned me to follow him and we left that phase of our lives behind us. Rabbi David Kahane, who had been our father’s friend, informed us that our parents did not survive and arranged a new home for me with Mother Tola and for my brother with another family.

These were some of the thoughts that tempered our joy during that celebration on VE Day. For us, this was not a culmination, but rather an important milestone on the road to recovery.

In 1945, Mother Tola and I were repatriated to Poland and in 1946 we were fortunate to be admitted to England temporarily. We had signed up to immigrate to the United States and we were finally granted permission to do so in 1949.

It has been observed that as a group, survivors have been unusually successful and have made important contributions to their new societies. That was certainly true of our little group: Oded Amarant rejoined his parents in Israel and became a successful engineer; Daniel Adam Rotfeld remained in Poland and became a successful writer, diplomat, disarmament expert, and foreign minister; my brother became a professor of physics in Australia, made major contributions to the field of X-ray crystallography, and developed a computer method for writing Chinese characters; I was the founding chair of pediatric cardiology at Hartford Hospital and Connecticut Children’s Medical Center and taught many successive classes of medical students as clinical professor at University of Connecticut School of Medicine; and the little boy hidden in Mr. Dyuk’s attic was Roald Hoffman, who became professor of chemistry at Cornell and a Nobel laureate. I have often been asked to explain this success. I am not sure, but I wonder whether the reason was that we didn’t take survival for granted but rather as a gift, which we had to justify. This makes one wonder about the many contributions humanity has missed because no one took the trouble of saving the 1.5 million children who perished.

Dr. Leon Chameides was founding chair of pediatric cardiology at Hartford Hospital and Connecticut Children’s Medical Center and is clinical professor at the University of Connecticut School of Medicine.

Explore!

Receive each beautiful and informative issue — Subscribe Today!

Voices of Hope is a nonprofit educational organization created by descendants of Holocaust survivors from across Connecticut to connect people to the inhumanity of the Holocaust and other genocides through educational and community programming. Visit ctvoicesforhope.org.

Read more stories about Connecticut in World War II in our Fall 2020 Issue and on our Connecticut at War TOPICS page.

Read more stories about Notable Connecticans on our TOPICS page.