Connecticut State Capitol, 210 Capitol Avenue, Hartford, 1878.

Hall of the State House of Representatives after restoration, 1986. Photo: © Robert Benson Photography

By Mary M. Donohue

(c) Connecticut Explored Spring 2022

All photos courtesy of John Canning & Co.

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

When I was a tiny child sitting in hard oak church pews on Sunday mornings, I could always get lost looking up at the ceiling covered in gold stars against a dark night sky or the light reflecting from the gold-leaf halos of the saints painted on the walls around the sanctuary. Closer inspection, though, revealed simple plaster column capitals made to look like the finest Italian marble and flat plaster walls painted to look like the most expensive limestone. My church and others in my hometown were erected in the 19th century by immigrant communities—Irish, German, Hungarian, and Polish, among them. If they couldn’t afford the best materials, they could use the services of a church decorator to make it look like they could.

The Connecticut State Capitol’s magnificent interior (built 1872 – 1879) in the Aesthetic style is a fine example of this phenomenon of creating the look of something grand. Christopher Wigren described the capitol interior in Connecticut Architecture: Stories of 100 Places (Wesleyan University Press, 2020) writing, “Carving, painting, stained glass, and patterned pavements create an all-over sense of pattern and texture. Many of the motifs are abstracted from nature, from stylized leaves and flowers to a constellation of stars high in the dome.”

Scottish immigrant William James McPherson, listed in the Boston directories in the 1870s as a decorative painter, is responsible for the capitol’s wall stenciling, lighting fixtures, and stained-glass design. McPherson, who trained in Scotland, was described by Alfred Mullett, federal architect for the U.S. Treasury (quoted in Antoinette J. Lee’s Architects to the Nation (Oxford University Press, 2000)) as “possessing exquisite taste” and as “the most accomplished architectural decorator in the United States.”

But by the 1980s, much of the capitol’s stenciling had been painted over or removed. This occurred as tastes changed and as spaces were partitioned to create more offices. The Hartford Courant reported on June 2, 1984 that the building, which had come close to demolition in the 1960s, had received a $20 million restoration. As part of that project, John Canning & Co. of Cheshire was commissioned to restore the interior stenciling through conservation of what had survived and replication of what had been lost. Like McPherson, John Canning is a Scottish immigrant and originally trained in church decoration. Canning immigrated to Connecticut in the 1970s, and the capitol interior restoration was one of his early projects—and one of his favorites.

Though materials may be modest, many highly-skilled techniques are required to accurately restore historic interior finishes such as those at the capitol. Stencils are cut to ensure that a pattern can be painted many times to create an overall effect. Gilding is a decorative technique of applying a very thin coating of either gold or silver leaf to a surface. Faux finishes include wood graining where several colors of paint and specialized tools are used to imitate a specific wood, usually a rare or expensive variety like mahogany, or marbleizing to imitate the appearance of polished marble.

After historic interiors are “modernized” or “updated,” finding what was originally there takes detective work. Sometimes, researchers can find historic photographs, prints, or architectural drawings that illustrate the original design. Newspaper descriptions might mention the color scheme. Conservators and craftsmen can carefully remove layers of paint to expose earlier wall finishes.

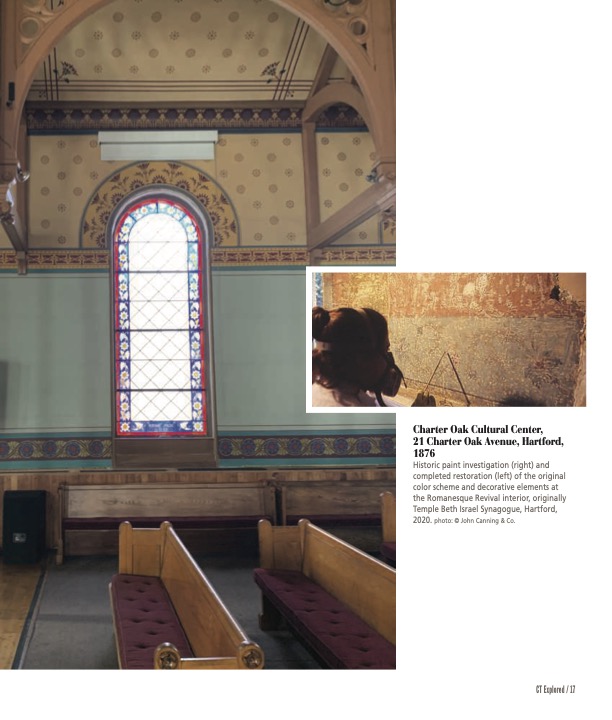

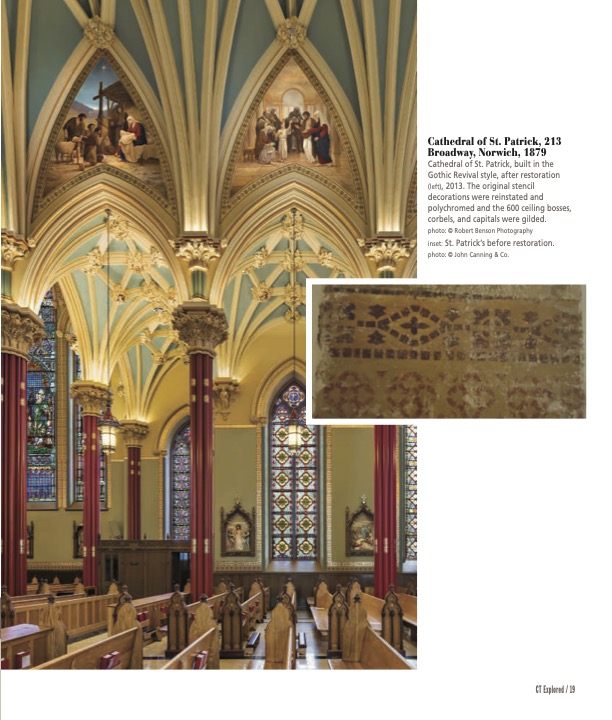

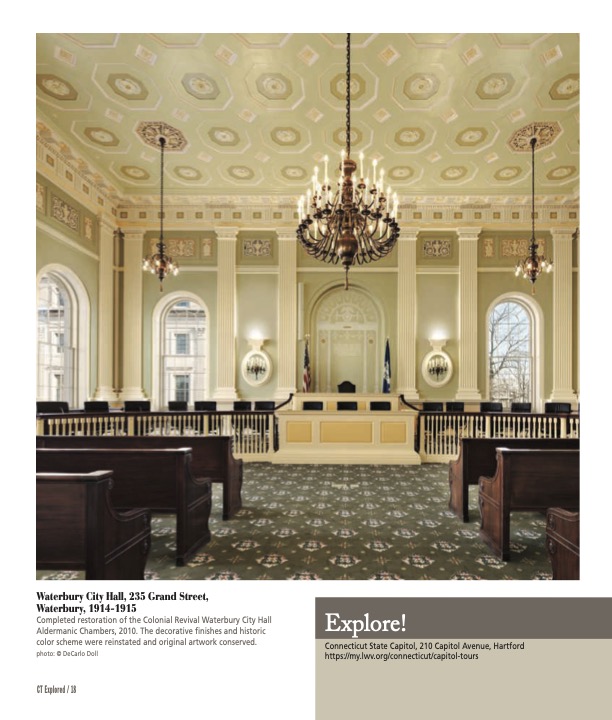

Canning has restored dozens of projects in Connecticut. When his firm investigated Charter Oak Cultural Center in Hartford (formerly Temple Beth Israel) in Hartford, it found four layers of wall stenciling in the former sanctuary. The firm’s work at the Cathedral of St. Patrick in Norwich included restoring the original vibrant polychrome color scheme and gold leaf to accent ornate foliated Gothic Revival ceiling bosses found at the top of the “ribs” of the Gothic arches. The firm’s work at Waterbury City Hall began with determining the original restrained and elegant Colonial Revival color scheme of cream, yellow, and pale green and restoration of plaster elements.

It can be a challenge today to find craftsmen who are trained in this work. In 2021 Preservation Connecticut presented the Janet Jainschigg Award for Preservation Professionals to John Canning & Co. for its work in interior restoration. People are sometimes surprised that these traditional crafts are still practiced. Here we feature some examples of John Canning & Co.’s work around the state.

Mary Donohue is the assistant publisher of Connecticut Explored and co-producer of Grating the Nutmeg, the podcast of Connecticut history. She last wrote “Building Art of Clay,” Fall 2021.

Waterbury City Hall, 235 Grand Street, Waterbury, 1914-1915. Completed restoration of the Colonial Revival Waterbury City Hall Aldermanic Chambers, 2010. photo: (c) DeCarlo Doll

GO TO NEXT STORY

GO BACK TO SPRING 2022 CONTENTS