(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Fall 2021

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

In 1882 the City of Hartford held a design competition for its proposed Civil War memorial. To be located in the city’s downtown gem, Bushnell Park, and within eyeshot of the shimmering white marble State Capitol, the memorial was to combine a triumphal arch and a bridge over the Park River. Fifteen entries were received, but a design review committee determined all were too expensive to build.

Soldiers and Sailors Memorial Arch, Hartford, 2011. photo: Carol M. Highsmith, The George F. Landegger Collection of Connecticut Photographs in Carol M. Highsmith’s America, Library of Congress

Hartford architect George Keller came up with a solution, notes David Ransom in his survey of Civil War monuments published by the Connecticut Historical Society (1997): place the arch adjacent to the existing Ford Street bridge (rather than build a new bridge) and substitute inexpensive building materials such as local sandstone and terracotta for marble and bronze.

Terracotta (variously spelled terra cotta or terra-cotta) is a clay-based, fired earthenware that can be used glazed or unglazed. It can be mass produced from molds or hand sculpted by craftsmen to make custom pieces. Keller got a recommendation for the Boston Terra Cotta Company from General Montgomery Meigs, architect of the New Pension Building in Washington, D.C. Meigs wrote to Keller, “No material known to art is better adapted to take the finest lines, touches, and forms of the sculptor’s own hand…. Nothing but deliberate violence … will destroy it. Boston Terra Cotta Company can be relied on… .” The company was contracted to create broad friezes of bas-relief sculpture for the Hartford memorial.

The north façade frieze, by sculptor Samuel Kitson, tells the story of the war; the south façade frieze, by sculptor Casper Buberl, tells the story of peace. The project suffered a setback when, the Boston Globe reported in 1884, a huge fire at the Boston Terra Cotta Company caused “A Fine Piece of Memorial Work in process of construction … for a military memorial for the city of Hartford…” to be “wholly ruined by water.” Work continued, however, and on September 17, 1886, the 24th anniversary of the Battle of Antietam, the Soldiers and Sailors Memorial Arch was dedicated.

Nancy K. Jones, in her thesis for Tufts University (2000), documents that The Boston Terra Cotta Company was the longest operating terracotta manufacturing facility in 19th-century New England, though it was only in business from 1880 to 1893. One of the company’s organizers, James Taylor, an English terracotta expert, emigrated to the United States in 1870, becoming known as the “Father of American Terra-Cotta makers,” Jones notes. Among dozens of commissions, the company produced vigorously modeled art and ornamentation for three Connecticut masterpieces: the Soldiers and Sailors Memorial Arch and Goodwin Building in Hartford, and the Barnum Museum in Bridgeport.

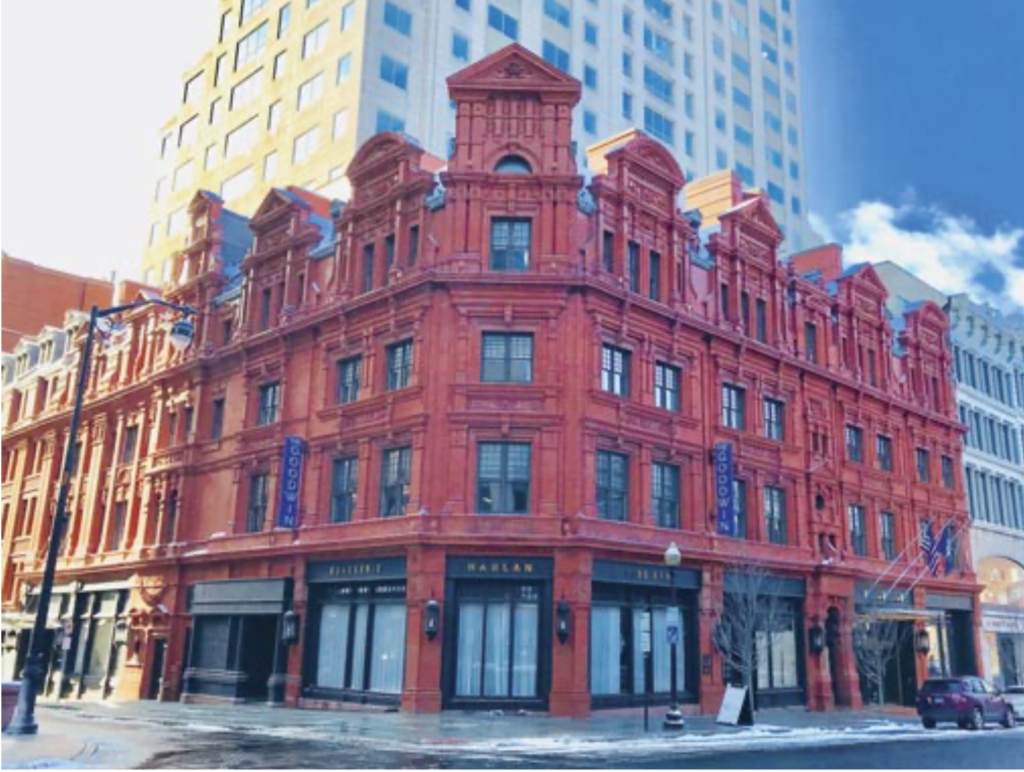

The Goodwin Building

In the 1880s, prominent Hartfordites James J. Goodwin and Rev. Francis Goodwin, who dabbled in real estate, commissioned architect Francis H. Kimball of Kimball & Wisedell to design a prestigious apartment building. As Andrews and Ransom note in Structures and Styles, Guided Tours of Hartford Architecture (Connecticut Historical Society, 1988), Kimball had the opportunity while working in for a London architect to observe English Queen Anne-style buildings ornamented with architectural terracotta. So, when the Rev. Goodwin returned from a trip to England and requested that style of architecture, Kimball knew exactly what Goodwin envisioned.

Detail of the Boston Terra Cotta Company decorative elements on the Goodwin Building, 2017. photo: Mary M. Donohue

The Goodwin Building was constructed in three phases in the 1880s, combining red brick with an ornate web of terracotta plaques and bas reliefs produced by the Boston Terra Cotta Company. The building was featured in the company’s 1884 catalog. Ransom, in Biographical Dictionary of Hartford Architects (The Connecticut Historical Society Bulletin, Winter/Spring 1989), asserts, “The result is Hartford’s ultimate statement in surface decoration… .”

The Goodwin Building’s facadectomy a century later, in 1985 – 1986, in which only the façade of the building was saved, aroused public ire. By then the apartment building was popular among musicians and artists. In a Hartford Couranteditorial (March 4, 1985) “An Ambiguous Proposal for a Faceless Building,” preservationist Anne Kuckro derided developers Goodwin Square Associates’s proposal to retain the shell of the historic building to hide an 8-story parking garage and to add a 16-story office building above. Ultimately, the Hartford City Council voted 5 to 4 in favor of the developer’s plan, and the building’s Arts and Crafts-style interior was gutted to allow construction of the tower. But its exquisite terracotta and brick façade was saved.

P.T. Barnum Makes a Gift to Bridgeport

One of museum and circus impresario P. T. Barnum’s last contributions to his beloved Bridgeport was a new building, the Barnum Institute of Science and History, now the Barnum Museum. Barnum donated the funds and land, chose the local architectural firm of Longstaff & Hurd, and approved the architectural plans—but died in 1891 before seeing it completed in 1893. An elaborate terracotta bas-relief frieze under the museum’s dome portrays the city’s history in themes, including the Civil War and the Industrial Revolution, and busts of luminaries such as George Washington and Grover Cleveland. In 1891 the Bridgeport Daily Standard noted, “As will be seen, [the museum]is a triumph of architectural taste and skill, and will be a building that can always be pointed to by the citizens of Bridgeport with pride.”

Mary M. Donohue is an architectural historian, assistant publisher of Connecticut Explored, and a frequent contributor to the magazine and co-host of Grating the Nutmeg. She last wrote “Bridgeport’s Crystal Palace” and “Connecticut’s Green Book Sites,” Spring 2020.

Explore!

Read all of our historic preservation stories on our TOPICS page.

GO TO NEXT STORY

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!