By Morgan Bengel

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Winter 2021-2022

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

William Stuart is a dynamic character in Connecticut’s history who has been identified in many different ways. Stuart recognized himself as a counterfeiter and rogue, and yet he also considered himself the hero of his own story. Captain Elam Tuller, the warden at New-Gate Prison during Stuart’s incarceration, frequently claimed that Stuart was the devil. In modern times, author Ray Bendici classified him as one of the “Jerks in Connecticut History.”

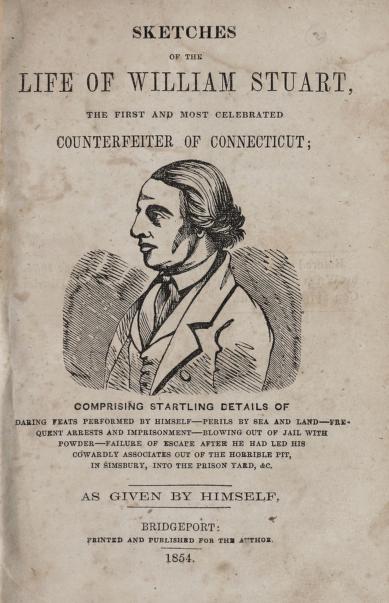

Born in Wilton, Connecticut in 1788, Stuart was sentenced at age 37 to five years at New-Gate for passing counterfeit money. In his autobiography, Sketches of the Life of William Stuart, The First and Most Celebrated Counterfeiter of Connecticut, (1854) Stuart recounts his experience serving time at there from 1820 to 1825. Through his many stories, anecdotes, and musings about the criminal justice system, Stuart regales his readers with a colorful picture of life at New-Gate. He maintains a light-hearted voice throughout but spares no detail of the cruelty, starvation, and putrid conditions in the prison. In this excerpt, he boastfully recounts his ability to stand up against his jailers, even if that simply meant making counterfeit coins while in prison. His autobiography paints a picture of a man who was not beaten down by the system, but instead held onto his humanity above all else.

Most of the prisoners were afraid of Capt. Tuller, and when he passed about the shops, they would take off their hats in blind servility; but I was never a worshiper of man, much less of a brute, though he were clad with epaulets, with a sword hanging to his side. Capt. T. and I had frequent controversies about provisions, excessive labor, and the menial services of the prison. It seemed a pleasure to him to annoy these poor fellows, and he would drive them about as a Shepard does his sheep. But I toed the mark with him, and fearlessly claimed my rights, my rations, and any thing that I ought to have. I have seen him thrash the men with his sword, because they begged for food to satisfy the cravings of hunger, but he never struck me, for fear of the consequences. I looked him in the eyes, was stern and resolute, and he respected me for it; yet still he oftentimes threatened me with punishment, and then I jeered and laughed at him.

I was sent here as a counterfeiter, and I was frequently engaged in making soap, and as my cooper’s trade furnished me with chalk to make the barrel hoops adhere to the staves. I cut out molds in two fragments of pine boards, filled them with finely levigated chalk, and then inserted a 25 cent piece in the chalk and squeezed my mold together; then I took them apart, bought pewter buttons from the prisoners, melted them down and run the metal in my molds. Thus, I coined money and bought my small stores off Beach the merchant. Before he was aware of the fraud, I had passed ten dollars upon him, all in my prison coined 25 cent pieces. Frequently, men from the towns about came to traffic with the prisoners, and bought herring and other fish of one of them, and paid him in twenty-five cent pewter money, and he went out to the tavern to settle his bill. The money I paid him he handed to the landlord, who looked at the coins, and asked him, “Where did you get this?” He said, “of a prisoner.” “Ah,” said Beach, “they make it there, and I got ten dollars before I found it out.” He came back to Capt. Tuller and told his story, and Capt. Walked into the ships with him to show him the rogue. He soon pointed me out, and Tuller said, “Oh you devil, are you making counterfeit money here?” “No,” said I. “Have you got more in your pockets?” “No sir.” “Let me feel,” and he put his hand in and took out three dollars untrimmed and just as they were molded, and then handed them back to me. “What do you make them for?” I replied, “I was sent here for counterfeiting, and I shall lose my skill unless I do a little at the business.” “Stuart, I believe that you are the devil” and then turned to the visitor and said, “if you deal with these fellows, you must look out for yourself.” Tuller said, “we shall have you back here!” I said, “won’t you wait, Capt. Tuller, until I get out?”

Aerial photograph showing Old New-Gate Prison’s ruins and buildings as they stand today, 2020. photo: Capture LLC., State Historic Preservation Office, State of Connecticut

Two years after Stuart’s release, New-Gate Prison was closed and all prisoners were transferred to a new prison in Wethersfield. For more about Stuart and New-Gate Prison, see Explore!, below.

Morgan Bengel is the curator and site administrator for Old New-Gate Prison & Copper Mine.

Connecticut Explored received support for this publication from the State Historic Preservation Office of the Department of Economic and Community Development with funds from the Community Investment Act of the State of Connecticut.

Connecticut Explored received support for this publication from the State Historic Preservation Office of the Department of Economic and Community Development with funds from the Community Investment Act of the State of Connecticut.

Explore!

“Connecticut’s First—and Most Celebrated—Counterfeiter,” Winter 2008/2009

“Escape From New-Gate Prison,” Summer 2006

Grating the Nutmeg Episode 17: “A Pirate’s Tale & Visit to New-Gate Prison” CTExplored.org/listen or Gratingthenutmeg.libsyn.com

“Wethersfield State Prison,” Fall 2016

Old New-Gate Prison and Copper Mine

115 Newgate Road, East Granby

Open seasonally, May to October, but you’ll find virtual tours at

portal.ct.gov/ECD-OldNewGate.

GO TO NEXT STORY

GO BACK TO WINTER 2021-2022 CONTENTS