(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Winter 2008/2009

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

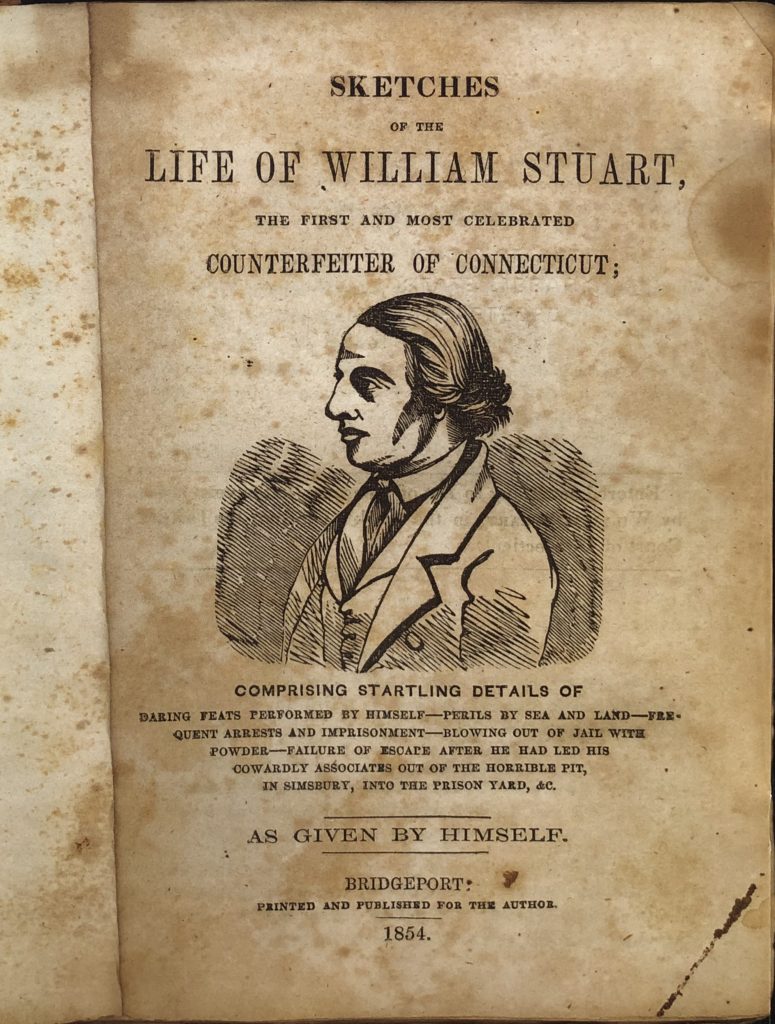

William Stuart was a rogue and proud of it. The title page of his 1854 autobiography promised that the narrative therein would include “startling details of daring feats performed by himself — perils by sea and land – frequent arrests and imprisonment – blowing out of jail with powder – failure of escape after he had led his cowardly associates out of the horrible pit in Simsbury, into the prison yard, &c.” A rogue indeed, and definitely not modest!

William Stuart was a rogue and proud of it. The title page of his 1854 autobiography promised that the narrative therein would include “startling details of daring feats performed by himself — perils by sea and land – frequent arrests and imprisonment – blowing out of jail with powder – failure of escape after he had led his cowardly associates out of the horrible pit in Simsbury, into the prison yard, &c.” A rogue indeed, and definitely not modest!

Stuart was born in Wilton in 1788, son of a farmer. From a young age he loved to cause trouble and play tricks on others. He claimed to have gained the reputation of being, in his terms, a “demi-devil” by the time he was 10 years old. To provide funds for his “frolics,” Stuart hammered sixpences into shillings and turned melted pewter into quarters. He was arrested for the first time when he was about 16 years old for an incident that went beyond roguery: throwing a prostitute named Poll Rider into a fire. When asked by court why he had done so, he replied “I had read of burnt offerings to the Lord, and it was my intention, by …throwing her upon the fire, to make a burnt offering to the Devil.” He paid a fine using money inherited from his father.

Soon after, around 1804, Stuart traveled to Susquehanna, Pennsylvania to live with his uncle. In between hunting and lumbering, he enjoyed “rowdyism, drunkenness, profanity, gambling, and debaucheries [while]… by day continually annoying some man or brute, committing mischievous pranks and petty thefts…” Returning to Connecticut after a year, Stuart found the quiet life in the land of steady habits to have little appeal. He was carousing with a friend, Joseph Mills, in a Norwalk tavern when they were approached by a mysterious stranger who offered to sell them counterfeit bank bills. Stuart was intrigued and exchanged his horse and saddle for a roll of counterfeit bills. To his delight, these were readily accepted by merchants.

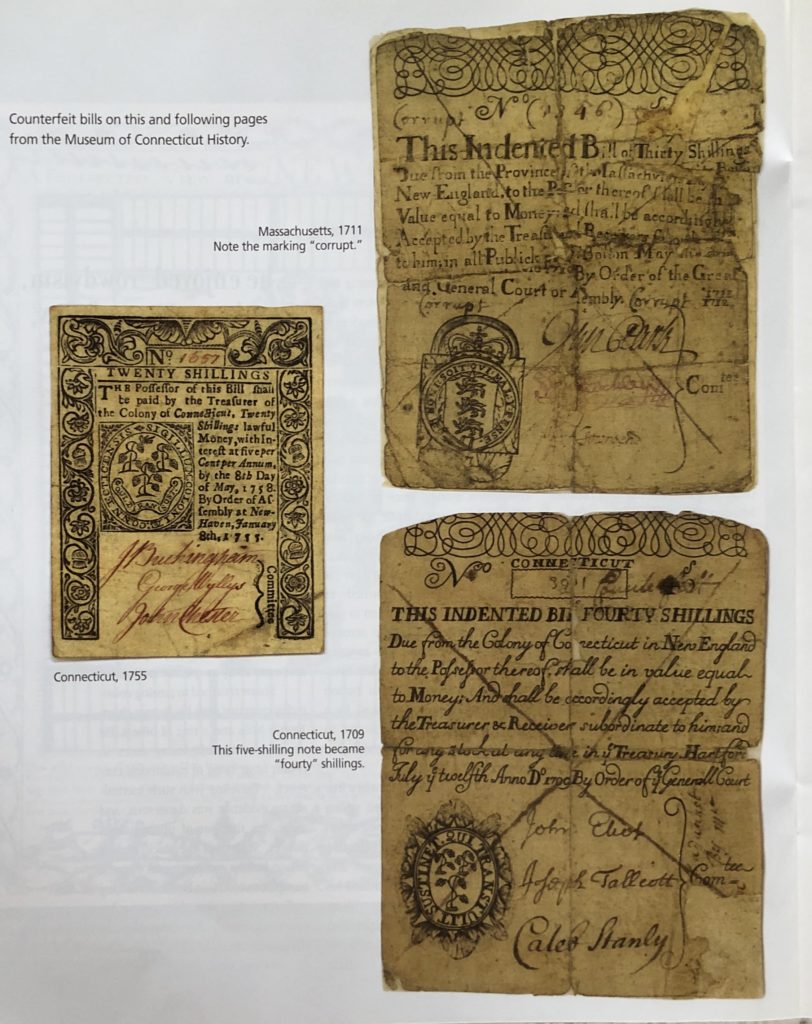

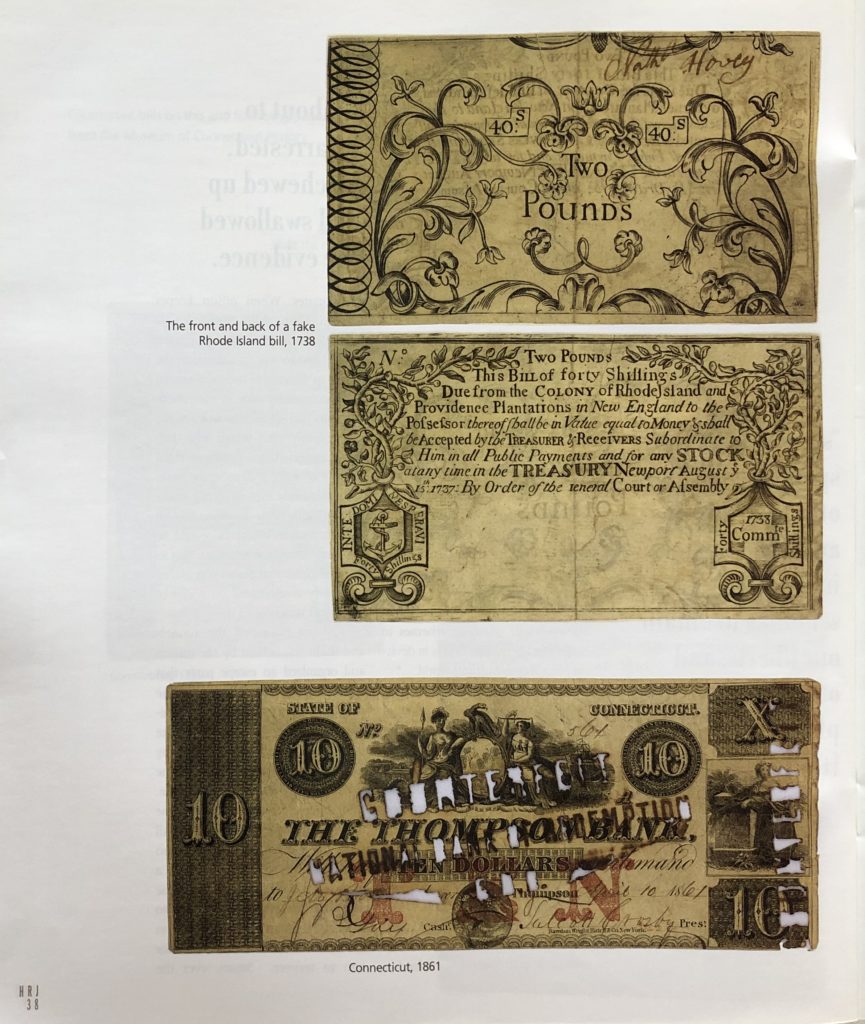

There was no federally issued paper currency at the turn of the 19th century; instead, the 16 individual states that then existed chartered banks that had the right to issue their own bills. By 1815 nearly 200 banks were doing this, which made it difficult for the average person to identify legal tender. Detecting aids were published, but of course they were also used by enterprising counterfeiters. Lower Canada, now Quebec, was the center of a thriving world of counterfeiters producing fake American currency. The Canadian-produced bills were wholesaled to couriers who delivered bundles to central points, where they were picked up by individuals who sold smaller packets to others who actually passed the bills.

Stuart describes his first purchase as “Burroughs’ money.” Stephen Burroughs was a noted counterfeiter in Lower Canada and a folk hero for his many jail escapes. Seneca Paige was an even bigger producer of counterfeit currency and in the 1820s the leading supplier to the United States. William Crane ran another counterfeiting operation, and it is to him that Stuart went when he needed more bills. Stuart provided Crane’s engravers with examples of genuine paper currency; after waiting there for just over a week, he had a fresh supply of counterfeit bills to pass.

Narrow Escapes

After nearly two years of passing bad money in Connecticut and New York, Stuart thought it would be prudent to go elsewhere. He went to Philadelphia, where he was double-crossed by a fellow passer of counterfeit money. However, having a premonition of approaching law officers, he hid his stash of counterfeit bills in the other person’s desk. Stuart was able to refute the charge of passing counterfeit money, since he had no bills on his person, while the other individual was found guilty and sentenced to prison.

Stuart then moved on to Baltimore, where he formed an alliance with a young woman to pass counterfeit bills. But he was arrested and jailed. While he was awaiting trial, his accomplice passed him black powder by placing it on a button lowered from his cell window by a thread. Stuart used the explosive to blow his way out of his cell and escape.

Stuart’s next associate was a free mulatto. His scam involved selling the man into slavery and then assisting in his escape to freedom. The two would travel to a new town and repeat the trick. Stuart continued his career of petty crime, alone or with an accomplice, up and down the East Coast. He returned to Connecticut again and married, but, he later wrote, his “rambling propensities drove me away in speculation again.”

Stuart returned to passing counterfeit currency with his former chum Joseph Mills and a ring of others. He traveled to Canada many times to obtain large sums of counterfeit currency. Traveling with such incriminating evidence was dangerous, and there was the fear of unscrupulous thieves. Stuart hid the thick wad of bills in hollow compartments of commonplace objects- a bottle, a walking staff- and thus was able to save his cache in several compromising situations. Once, as he was about to be arrested, he chewed up and swallowed the evidence. In addition to obtaining bills from Canada, the gang developed a system of altering good bills to increase their value. Stuart also repeated his sell/steal back con routine, only this time with horses.

A Stint in New Gate

Ironically, Stuart was leaving Connecticut to embark on a crime spree in Georgia when he inadvertently used a counterfeit bill to purchase a handkerchief in Ridgefield and was apprehended. While he sat in the Danbury jail awaiting trial, officials offered to save him from being sent to prison if he informed on the other members of the counterfeit ring. He refused. Stuart was sentenced to five years imprisonment on January 19, 1820. He was 37 years old.

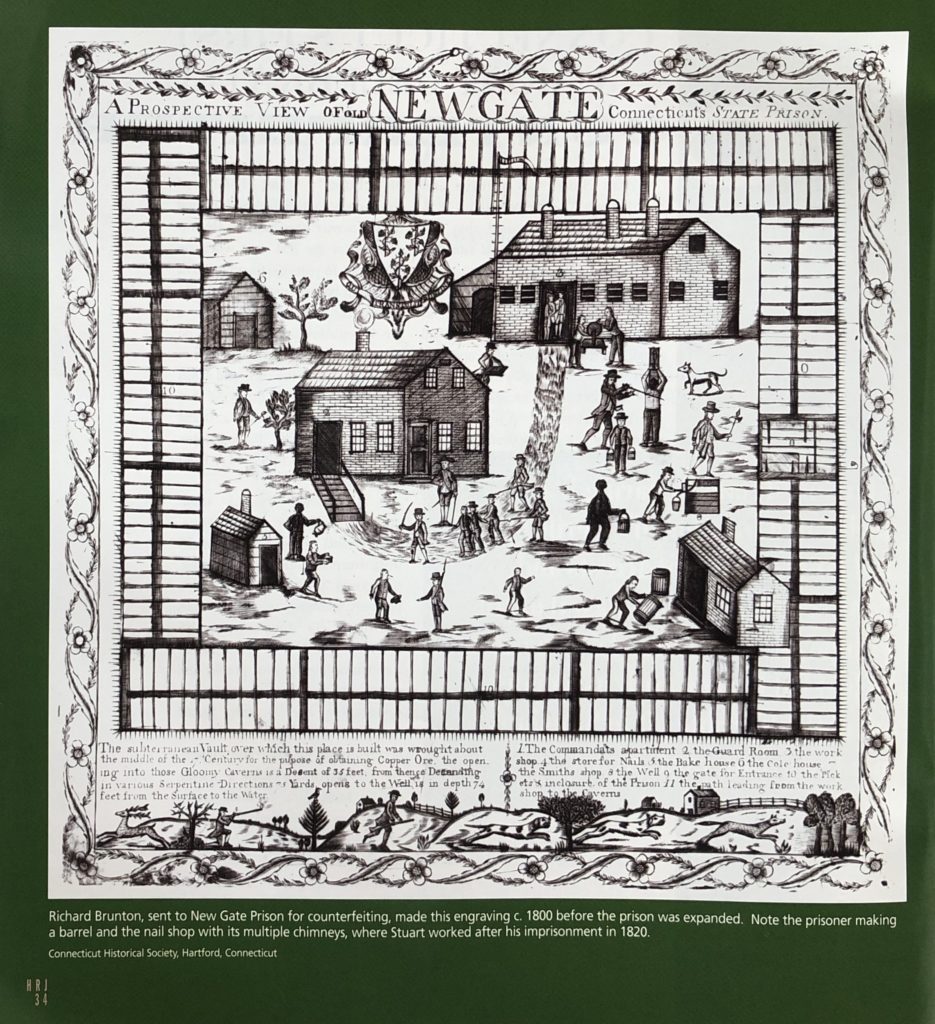

Richard Brunton, sent to New Gate Prison for counterfeiting, made this engraving c. 1800 before the prison was expanded. Note the prisoner making a barrel and the ail shop with its multiple chimneys, where Stuart worked after his imprisonment in 1820. Connecticut Historical Society, Hartford, Connecticut

In 1820 convicted criminals were sent to serve their sentences at New Gate Prison in what was then the town of Granby. Sometimes referred to as a work house, the prison was established in 1773 with the intent of using inmate labor to mine copper ore. When Stuart arrived, joining 57 other prisoners, mining operations had long been abandoned, and prisoners worked making barrels, shoes, or nails that were sold to offset prison expenses. A guardhouse, workshops, some prison housing, and various support buildings were located on an acre of uneven ground within a 12-food stone wall. The underground mine tunnels were used for prisoner sleeping quarters. Stuart liked being underground. He felt the damp restricted vermin and that the constant year-round temperature made the place healthy. Best of all, the prisoners were mostly unsupervised. They would steal bits of tallow to use for light, and, according to Stuart, “some nights were spent in gambling, others in fiddling and dancing, others in arranging schemes to obtain our liberty, and others in devising plans to punish [the]world…”

Although he chafed at wearing ankle shackles connected by a foot of chain, Stuart quickly adapted to his prison situation. He soon was able to make two barrels per day and had free time to make wooden items for sale. He used to income to buy extra food and rum from the tavern across the road. He further supplemented his funds by melting down pewter buttons and making counterfeit coins. Tavern keeper Luke Viets soon learned to beware of Stuart’s coins, but Stuart was able to fool vendors who came to the prison to sell food to the inmates.

When prison keeper Captain Elam Tuller insisted that Stuart make three barrels a day, Stuart refused and so was transferred to the nail shop to perform the most menial and ignominious trade at the prison. Prisoners had six months to learn the skill properly, after which time they were expected to produce eight pounds of nails a day. Stuart again learned quickly but sat doing nothing- drinking rum- knowing that he had six months before he would be required to meet the set quota. This so angered Tuller that Stuart was placed in solitary confinement on a diet of bread and water for 12 days.

Stuart examined the tunnels and shafts left behind by the miners and organized an escape party that worked every night digging to the surface. Unfortunately, another prisoner ratted on the plans, so the would-be escapees were greeted by musket fire when they reached the surface and peeked out the hole. Undaunted, Stuart saw a new escape opportunity while working in the nail shop. In 1823 he led an insurrection there, but his ambitious plan for a mass escape failed when most of the other prisoners were too frightened to participate. Stuart was badly hurt in the melee, and it took some time for him to recover. Stuart, ever the confidence man, used the situation to his advantage. He pretended to be lamer than he was and would deliberately fall down and groan as if in great pain. He also kept his wound from healing.

Prisoners were liable for their living expenses and the cost of their trial, and the prison keeper could hold a prisoner until these expenses had been paid at the rate of $5 per month. Although Stuart had served his court-designated sentence, he owed $375 and therefore needed to stay at New Gate for an additional six years. The prison keeper had the power to forgive such debt if the prisoner was unhealthy and a charge to the state. Stuart played on his infirmities, and Captain Tuller finally agreed to release him upon payment of $20, which Stuart borrowed. Once outside the prison walls, Stuart threw away his crutches and hung around Viets Tavern drinking rum and taunting Tuller. Tuller said, “Had I known that you could move about so easily; I would have kept you here as long as grass grows and water runs.”

Stuart Settles Down…Sort Of

Eventually tired of the game, Stuart returned to his long-suffering family in Bridgewater. Stuart resumed farming and avoided his former colleagues in the counterfeiting ring. Nor did Smith, his partner in the nail shop insurrection, succeed in luring Stuart back to a life of crime. When caught stealing horses, Smith implicated Stuart. Stuart was able to prove that he had been at home tending his sick daughter the night when the horse in question was stolen, and charges were dismissed.

When he was 66, Stuart published his autobiography detailing his exploits and adventures; this is our only source of information about him, and it leaves us in the dark about such key details as when and how Stuart died. He stated that he wrote his story because [he was]… “getting advanced in life, and if I stand now as a beacon to warn the young and ambitious against vice and crime, my history will be a gain to the world.” However, it may have had the opposite effect: Stuart told his tale with such color that he made life as a criminal appealing and full of excitement!

Karin Peterson was museum director for the State Historic Preservation Office and member of the Connecticut Explored editorial team. She last wrote about The Kent Iron Furnace, Fall 2006.

READ MORE

“Escape from New-Gate Prison,” Summer 2006

“Counterfeiter William Stuart, Hero of his Own Story,” Winter 2021-22

LISTEN

Listen to our Grating the Nutmeg podcast about Old New-Gate Prison, episode 17