(c) Connecticut Explored Inc., Summer 2021

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

Mine Hill in Roxbury, Connecticut is a testament to both natural force and human effort. It was here that natural processes occurring over millennia placed rich deposits of iron minerals and granite, and here that humans laboring over decades attempted to extract and monetize those resources. Today preservationists work to maintain Mine Hill as a place of natural beauty, a reminder of human industry, and a legacy of the once-thriving—and now lost—community of Chalybes.

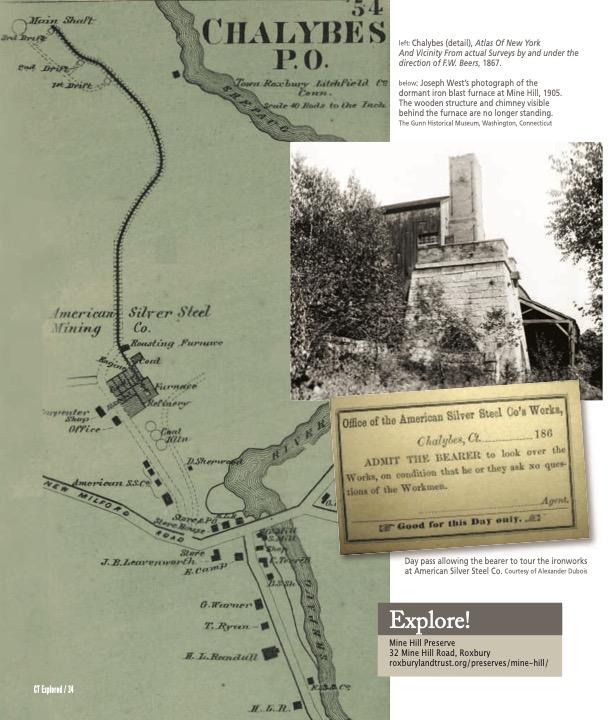

While mining and iron operations at Mine Hill ceased after 1872, the site bears permanent and striking reminders of human intervention. Michael Bell and Diane Mayerfield write in Time and the Land: The Story of Mine Hill (Roxbury Land Trust, 1982) that “traces of man’s quest for profit cover the hill, from clues as obvious as a blast furnace … to signs as subtle as a cluster of young hemlocks in the middle of a hardwood forest.” The remains at Mine Hill document a brief but intense period of iron and steel production in Roxbury.

The hill was mined as early as 1751, when Moses Hurlbut and Abel Hawley obtained a tract of land from the town. Soon after, brothers Abraham and Israel Brownson organized the site’s first large-scale mining operation and hired a German goldsmith by the name of Feuchter to oversee the excavations. William Cothren writes in History of Ancient Woodbury, Connecticut (William Cothren, 1872) that in 1764 a young Ethan Allen invested in the Brownson mining title, purchasing two and a half acres. A company of New York investors later leased the Brownson tract, employing as many as 33 miners and laborers. But these early ventures all targeted silver or lead deposits, not the considerable veins of siderite (iron carbonate) found there; as a result, none met with much success.

Benjamin Silliman, a professor of chemistry and mineralogy at Yale College, visited Mine Hill in 1817. In an 1820 issue of The American Journal of Science and Arts, Silliman reported that the hill’s rich spathic iron veins had been overlooked by previous excavations, for “tons of it lie here upon the ground, and no one in this vicinity appears to know what it is.” He further asserted that the siderite was similar to the ore used in German steelmaking and would afford “steel directly from the bar without the process of cementation,” which produced steel by heating iron and charcoal in a furnace. His assistant Charles Shepard wrote in the same publication in 1830 that “no value was attached by either of the companies to the Sparry Iron, which forms the main body of the vein … with their expectations wholly confined to silver, they entirely overlooked a metal, which … affords the surest and the most steady returns of all the substances which the earth contains.”

A proprietor named David Stiles invited Shepard to complete a mineralogical and geological survey of Mine Hill in 1830. After considering the situation and location of the hill, Shepard was authorized by Stiles to publish his findings in The American Journal and “submit it to the attention of capitalists, whether, a surer investment of capital can be made in our country; or one, which, on the whole, would prove more conducive to our national prosperity….”

After an ensuing and prolonged legal battle over the ownership of Mine Hill, Stiles sold the site to the Shepaug Spathic Iron and Steel Company in 1865. A major draw for the new company was the potential for steel production. Relying heavily on the earlier analysis, Shepaug Spathic quickly began iron smelting and steel production.

Between 1865 and 1868 Shepaug Spathic extended the mine tunnels and built a railbed to carry ore down the hill, where it was fed into two roasting ovens to remove gases that might otherwise cause problems in the furnace. Donkeys carried the empty carts back up the hill, while the roasted ore was crushed and mixed with flux (limestone or marble) before continuing to the blast furnace. Alternate loads of ore and charcoal were fed into the furnace, where the intense heat drove off further unwanted gases and separated impurities (known as slag) from the molten iron. The iron was then tapped through a hole and allowed to run into the casting bed, where it cooled into pig iron.

Despite having invested heavily in an integrated steelworks, the adjacent steel finery only operated until 1868, when the company moved steel production to Bridgeport and reorganized as the American Silver Steel Company. The iron furnaces at Mine Hill continued to turn out pig iron until 1872, according to Bell and Mayerfield.

The Mine Hill iron enterprise’s failure after just seven years was likely caused by a combination of factors. Robert Gordon in Technology and Culture (Vol. 24, No. 4, 1983) ascribed the failure to a “belief in the special properties of the siderite as an ore for making steel and faith in advice from experts … who had no practical experience with steelmaking.” The site experienced technical difficulties, though Bell and Mayerfield maintain that none should have been insurmountable. They suggest that the operation at Roxbury was simply “some ten years out of date.” Mine Hill was built to burn charcoal, while new furnaces achieved greater capacity running on coal or coke. In addition, Shepaug Spathic opted to refine steel through a German puddling technique when more effective processes were being introduced, and the site lacked railroad access until 1871 at a time when larger iron deposits were opening in the West.

On May 22, 1872 the American Silver Steel Company advertised in The Hartford Courant that both the Bridgeport steel works and Mine Hill iron complex would be sold at public auction. A detailed description of the site demonstrates the expansiveness of the Mine Hill operation, which included seven double-tenement homes and 1,200 acres of farm and woodland as part of the sale.

Meanwhile, an entire community had sprung up around the iron complex. Now all but vanished, this once-thriving village was called “Chalybes,” a reference to an ancient tribe known in mythology for its use of iron. According to Bell and Mayerfield, the village supported a post office, general store, school, lumber yard, coal yard, creamery, hat manufactory, cigar factory, hotel, and several boarding houses. Albert L. Hodge, manager of the iron mine, kept a well-patronized saloon and a dry goods store.

While it operated, Mine Hill’s iron industry was a major economic driver of Chalybes and the surrounding area. Hundreds of laborers flocked to the village and stayed in the boarding houses or at the hotel, among them a large number of immigrants from Poland, Germany, and other European countries. After the ironworks closed, Chalybes was renamed Roxbury Station, reflecting the importance of the Shepaug Valley Railroad to the granite quarries and other industries that continued to sustain the village for a time, until the railroad stopped operating in 1935. Three years later, many of the ironworks’ wooden buildings were destroyed by the Great New England Hurricane.

In 1978 the Roxbury Land Trust acquired the former iron complex from the Matthews family and established the 360-acre Mine Hill Preserve. The organization endeavored to preserve the site’s remaining historic fabric by stabilizing the blast furnace and stone walls, restoring the roasting ovens, conducting archaeological and environmental studies, and successfully nominating the iron mine and furnace complex to the National Register of Historic Places. The land trust also purchased, renovated, and now occupies the building that once served as a general store and post office for the Chalybes community.

Expanded over time to its current 450 acres, Mine Hill Preserve now contains four miles of trails that lead visitors past the remnants of Roxbury’s iron and granite industries. The main loop ascends the hill along the old “Donkey Trail,” past multiple gated tunnel entrances and air shafts, while the descent offers views of the abandoned quarries. The trail ends at the site of the furnace complex. Here visitors can inspect the roasting ovens and blast furnace and locate foundations for the power house, charcoal storage, and other buildings. Signposts mark the locations of nine of these lost structures, including the short-lived steel mill. Interpretive signs throughout the furnace complex reveal the rich history of Mine Hill, complete with historic photos, descriptions of the mining and smelting processes, and renderings of Chalybes during its heyday.

In Mine Hill visitors find a landscape that was torn open by more than a century of mining and manufacturing followed almost immediately by a century of relatively little human intervention. In their report for the land trust, Bell and Mayerfield describe a forest that has “reclaimed the land and healed most of the scars, demonstrating that the damage done by our use of the natural world is not necessarily irreparable.” Mine Hill illustrates that Connecticut’s historical and natural resources are often intertwined, as is perhaps best exemplified in the installation of “bat friendly” grating to reinforce the mine’s air shafts, which now serve as hibernacula (sites where bats hibernate over the winter). Like many places in Connecticut, Mine Hill is, most of all, a reminder of the beauty of our state and the lives of those who came before us.

Alexander Dubois is curator of the Litchfield Historical Society. He last wrote “A New Life for the Merwinsville Hotel,” Spring 2020.

Explore!

“The Kent Iron Furnace,” Fall 2006

Mine Hill Preserve

32 Mine Hill Road, Roxbury

roxburylandtrust.org/preserves/mine-hill/

GO TO NEXT STORY

GO BACK TO SUMMER 2021 CONTENTS

Subscribe/Buy the Issue

Sign up for our bi-weekly e-newsletter

for the latest stories, Grating the Nutmeg podcast,

and programs and exhibitions to see now!