(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Spring 2020

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

Transit-oriented development, which seeks to create vibrant communities around public transportation, has become a major trend in urban planning. But when railroad surveyors met at Sylvanus Merwin’s guest house in New Milford in 1837, transit-oriented business was not a burgeoning field. It was, instead, a novel opportunity.

The Housatonic Railroad was looking to open a line between Bridgeport, Connecticut and Pittsfield, Massachusetts. The company’s surveyors spent a few nights in Merwin’s guest house in Gaylordsville, a village in the northwest corner of New Milford. John Flynn writes in The History of Gaylordsville (Gaylordsville Historical Society, 2016) that the surveyors spent their evenings discussing the proposed railroad, allowing Merwin to learn “the exact path the rails would follow.” A shrewd businessman, Merwin purchased land and began constructing a hotel in the path of the proposed route.

When officials from the railroad arrived to negotiate a right-of-way through his property, Merwin set forth his conditions. In Country Depots in the Connecticut Hills (Goulet Printery, 1996) Robert L. Ford writes that Merwin insisted that the railroad use his hotel as a meal stop and ticket office, appoint him as the station agent, and call the station “Merwinsville.” With the terms agreed upon, Merwin erected a ticket office and waiting room on the south end of the hotel.

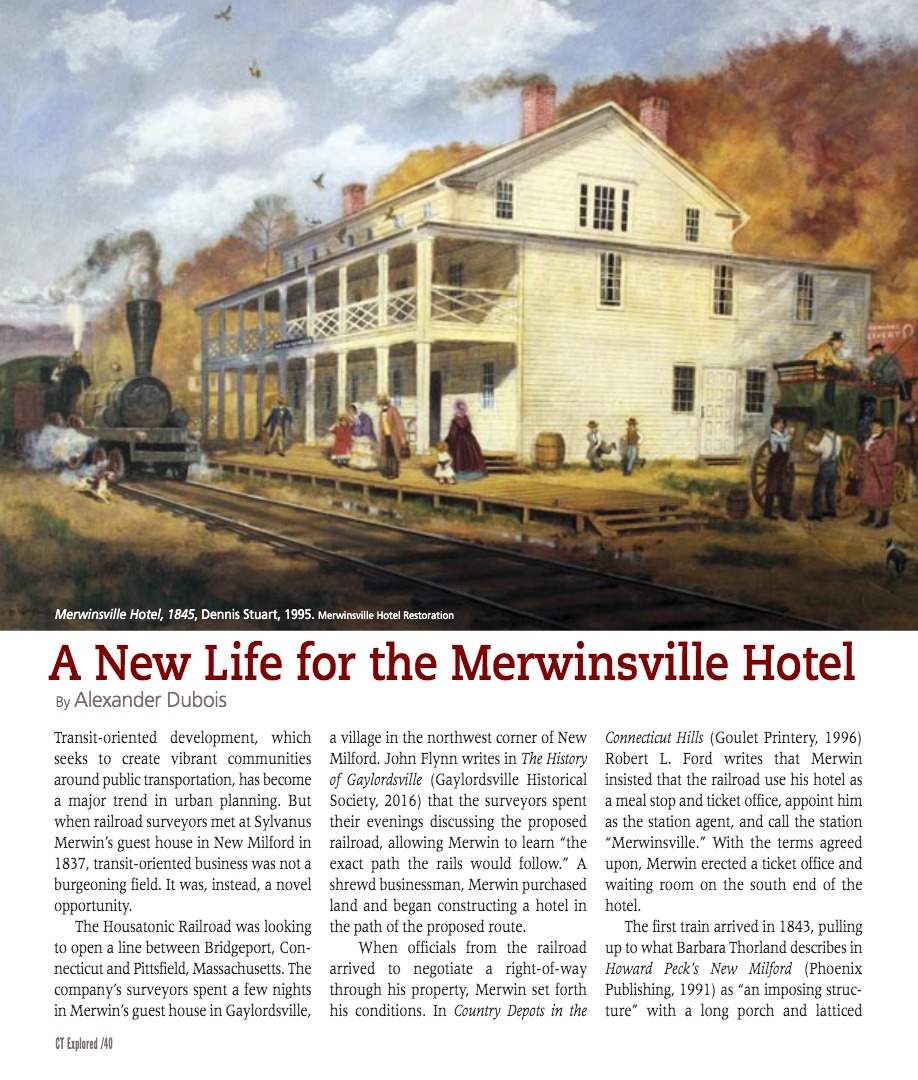

The first train arrived in 1843, pulling up to what Barbara Thorland describes in Howard Peck’s New Milford (Phoenix Publishing, 1991) as “an imposing structure” with a long porch and latticed second-floor balcony facing the platform. Merwin’s three-story hotel had a Georgian exterior with nine columns on each floor and six doors opening onto the porch. Inside, two sets of double staircases met at a striking central landing, with stairs leading up to the second-floor bedrooms and a third-floor ballroom.

With only 20 minutes for each stopover, meal service at the hotel was an impressive feat. Thorland notes that as the train drew into the station “amidst clouds of smoke,” a man would hurry down the porch ringing a dinner bell. Passengers would rush from the train into one of the four first-floor dining rooms. The food was cooked by Merwin’s wife, Flora, and her staff in the basement kitchen and bakery, and sent up to the dining rooms via a dumbwaiter. Diners paid 50 cents for a meal. By the 1850s as many as 10 to 12 customers arrived on each train, according to Flynn.

The Merwinsville Hotel became a center of community life. Merwin opened a store on the property and a school which he advertised in The New York Times (August 23, 1860) as a “family school for young ladies and boys.” According to the advertisement, 20 students would be “admitted to board” in Merwin’s hotel where they could “enjoy all the comforts of a home.” The hotel also served as a stop on the east-west stage route, housed the village’s post office for a time, and contained a telegraph office where people famously gathered on election nights, according to Thorland. The third-floor ballroom ran the length of the hotel and was lined on both sides with dressing rooms and lit by three chandeliers. Monthly square dances, dinners, and performances drew guests from the surrounding area.

On January 19, 1877, an article in The Hartford Courant announced that Housatonic Railroad passenger trains would no longer “make the usual stop at Merwinsville for refreshment.” An era of faster trains and the advent of dining cars brought the hotel’s meal contract to an end. Ed Hurd, Merwin’s son-in-law, was forced to discontinue the hotel business. The station, by then operating on the New York, New Haven and Hartford line, remained open until 1905 when the rail company replaced Hurd as station agent and moved the ticket office just south of the hotel. In 1918 a new station was renamed Gaylordsville.

A series of owners used the former hotel as a residence, a workshop, and a storage area. After a fire in 1970, the building was left vacant and in disrepair until local resident George Haase organized support for a restoration project and formed a nonprofit in 1974 to care for the building. The building was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1977.

Today the Merwinsville Hotel restoration is under the stewardship of a dedicated group of volunteers, including Haase’s two daughters. As a result of their continued efforts, Merwinsville is once again a center of community life in northwest Connecticut.

Alex Dubois is curator of collections at the Litchfield Historical Society. He last wrote “A State of Hard Drinkers,” Spring 2019.

Explore!

Merwinsville Hotel, 1 Browns Forge Road, Gaylordsville

merwinsvillehotel.org, 860-350-4443