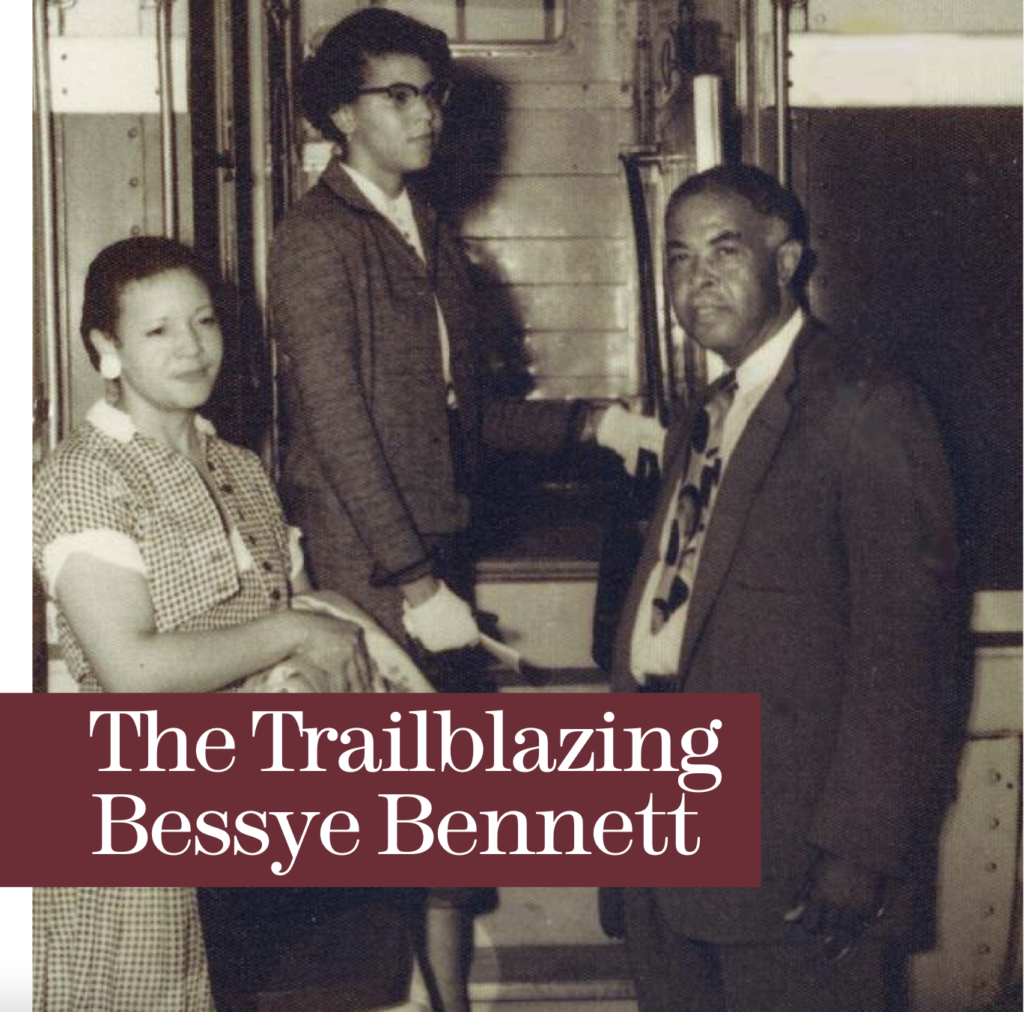

Bessye Anita Warren (later Bessye Warren Bennett), with her parents Samuel and Juanita Warren, boards the train from her home in Texas for Radcliffe College, now part of Harvard University, in Boston, Massachusetts, 1954. Courtesy of Dr. Vera Bennett Brown

By Constance Belton Green

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Spring 2014

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

The first African American woman to practice law in Connecticut was admitted to the bar in 1974—more than a century after African American women had been practicing law in other parts of the United States.

“If you are without a history, then you are without an identity,” wrote J. Clay Smith in his 1998 book Rebels in Law. Smith was referring to the little known stories about trailblazing African American women who practiced law—stories I call hidden historical treasures. These stories include those of women such as Charlotte E. Ray, who in 1872 became the first female African American lawyer in the United States, admitted to practice law in Washington, D.C. During the 19th century four African American women were admitted to the legal profession. In addition to Ray, Mary Ann Camberton Shadd Cary was admitted to practice law in Washington, D.C. in 1883, Ida Platt was admitted to practice law in Chicago in 1894, and, Lutie A. Lytle was admitted to practice law in Kansas and Tennessee in 1897.

Legal historian Barbara Babcock in “A Real Revolution,” (University of Kansas Law Review, vol. 49, 2001) explained, “Of all the professions that women sought to enter, the law was the most intransigent. Women could explain and excuse their presence in other professions by reference to their manly nature. Doctors could treat other women, thus preserving female modesty. Teachers were only extending the role of mothers as moral instructors. Even ministers could build on beliefs about women’s spirituality, but there was no way to sugarcoat the meaning of being a lawyer.” Babcock and Virginia Drachman have written extensively about women who entered the legal profession during the 19th and early 20th centuries. Little attention, however, has been given to the stories of African American women who faced the dual jeopardy discriminations related to race and gender in their pursuit of a profession in the law.

By 1922 there were 20 African American women practicing law in the United States. By 1950 there were 83 sprinkled throughout 19 states, primarily practicing in the more populated areas such as New York City, Chicago, and the District of Columbia. For example, by 1950 there were 19 African American female lawyers in New York, 10 in the District of Columbia, and 13 in Illinois.

The Emergence of African American Women Practicing Law in Connecticut

In 1882 Mary Hall became the first woman of any race (she was white) admitted to practice law in Connecticut. The judicial decision rendered by Chief Justice John Duane Park of the Connecticut Supreme Court in the case In Re Hall held that, “We are not to forget that all statutes are to be construed, as far as possible, in favor of equality of rights.” Hall had passed the licensing examination after studying law, and the applicable 1875 Connecticut statute on licensing made reference to “persons,” indicating no specific exclusion of women. The In Re Hall judicial decision was one of the first of its kind in the United States to support a woman’s right to practice law based on statutory interpretation.

Two years earlier, in 1880, the first African American male lawyer, Edwin Archer Randolph, a Yale University law graduate, was licensed to practice in Connecticut. Randolph was followed in 1881 by Walter Scott, another Yale University law graduate. Both Randolph and Scott relocated to Virginia, where there was a larger and potentially lucrative black client base. George W. Crawford, another Yale University law graduate, was the first African American to sustain a law practice in Connecticut. He established a New Haven law office in 1903. After winning several legal cases, Crawford was able to attract a racially diverse clientele.

Although there were still no African American women lawyers in Connecticut by 1950, there were two prominent African American women practicing in New York City who had Connecticut ties.

In 1931, Jane Bolin, born in Poughkeepsie, New York in 1908, was the first African American woman to graduate from Yale University’s law school. By her own admission her days as a Yale law student were challenging. Found among her papers at the Schomberg Center for Research and Culture are her reflections on her experience at Yale: “In law school there were a few who took pleasure in letting the swinging classroom door hit me in the face.”

After graduating from Yale, Bolin returned to Poughkeepsie and worked in her father’s law practice. By 1937 she moved to New York City and was appointed assistant corporation counsel for the City of New York. In 1939 she was appointed a judge in the Domestic Relations Court for the City of New York by Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia.; she was the first African American woman to serve as a judge in the United States. After her death on January 8, 2007, a New York Times obituary (January 10, 2007) referred to her as an “experienced judge” describing her as a “lady judge” with a combination of legal talent and impeccable style in fashion. Bolin’s portrait now hangs at Yale University’s law school.

Constance Baker Motley was born in New Haven, Connecticut on September 14, 1921. She attended Columbia University’s law school from 1943 to 1946. She interned with the NAACP Legal Defense Fund in 1945 and was hired by Thurgood Marshall, then chief counsel of the NAACP Legal Defense Fund. In her autobiography, Equal Justice Under Law, Baker Motley describes her experiences as a civil rights attorney: “I was on the ground level of the civil rights movement without even knowing it.” During her 20 years as a civil rights lawyer Baker Motley worked on many cases including Brown v. Board of Education (1954), which is credited with desegregating public schools, and Meredith v. Fair (1962). On January 25, 1966 Baker Motley was nominated by President Lyndon Johnson to serve on the United States District Court for the Southern District of New York, becoming the first African American woman to receive such a federal appointment. [See “Constance Baker Motley’s Chester (Connecticut) Retreat,” Summer 2021.]

The Story of Bessye Anita Warren Bennett

In 1960 there were 142 African American women practicing law in the United States. Yet when I entered the University of Connecticut’s law school in 1969 there were still no African American women practicing law in Connecticut. There were also no other female African American students at the University of Connecticut law school. My feelings of isolation are best described by one of my earliest experiences in Connecticut: finding housing in close proximity to the law school. I was from Virginia, and was unfamiliar with the West Hartford neighborhood. However, the law school provided first-year students with a list of neighboring homes that rented rooms to law students—a tradition, I was told. My father and I knocked on several suggested doors, but homeowner after homeowner responded that they had no rooms available or that they were no longer renting rooms to law students. Only with further assistance from the school was I eventually able to locate housing.

In 1970 I met Bessye Anita Warren Bennett at the University of Connecticut law school. She was starting her first year, and I was in my second year. Bessye was also already married and had three children.

Bessye was born in Prairie View, Texas, on August 16, 1938, the only child of Dr. Samuel F. Warren, a college professor, and Juanita McBroom Warren, a public school teacher and librarian. My parents were also educators. Bessye and I agreed: College was expected of us.

The Warrens moved to Baton Rouge, Louisiana, then moved again in 1948 when Samuel accepted a faculty position in economics at Texas Southern University. Bessye graduated from Yates High School in Houston in 1954 at age 16; she was the class valedictorian. She decided to leave Texas to attend Radcliffe College in Boston (now part of Harvard University), joining the journey toward higher education and employment opportunities known as the great migration for African Americans, a phenomenon described by Isabel Wilkerson in The Warmth of Other Suns (Random House, 2010).

Bessye graduated from Radcliffe College in 1958 with honors and was accepted at Harvard Law School. If she had gone to Harvard law she would have been among the first African American women to attend. The first was Lila Fenwick in 1956. However, she instead married her college sweetheart, John Bennett, in June 1958. John Bennett continued his studies at Harvard University and received a doctorate in applied mathematics in 1962. “The tuition was such at Harvard that I couldn’t go with my husband in graduate school,” Bessye told me.

In 1964 the Bennetts moved to Hartford, Connecticut with their three young children: Vera, born in 1959, John Jr., born in 1960, and Margaret, born in 1962. John held several successive positions in Hartford at United Technologies, eventually becoming director of data processing. Bessye set up her family’s household, joined the League of Women Voters, and taught in the Hartford Public School System. She worked outside the home, combining career and family as her mother had done before her. She also enrolled in a master’s in education program at Trinity College, receiving her degree in 1968. Her husband John told me in an August 2007 interview that even while she was teaching, “Bessye always dreamed of becoming a lawyer.”

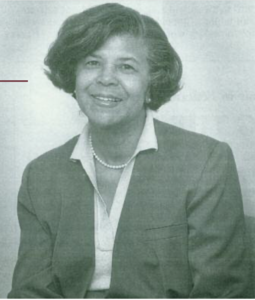

I graduated from UConn Law in 1972; Bessye graduated in 1973. She was admitted to the Connecticut bar in 1974, and I was admitted in 1975. She became the first African American woman to be licensed to practice law in Connecticut. “People were saying there was special treatment for Blacks and special programs,” she said in an article in the Connecticut Law Tribune (November 27, 1995). “That really wasn’t it. It was somehow their thinking about us that we were such an oddity.” I followed Bessye’s lead in combining work and family. By the time I graduated and passed the bar, I was also married and had a child.

By 1980 there were 4,272 female African American lawyers in the nation; according to U.S. census data, 16 of them were in Connecticut. Included in the list of the first African American women to be licensed to practice law in Connecticut between 1974 and 1979 besides Bessye and myself were Patricia Lilly Harleston, Linda Kelly, Johnese White Howard, Sheridan Moore, Curtissa Coffield, Cheryl Brown Watley, Marilyn Ward Ford, and Vanessa Bryant. “We need to nurture the sense that there is justice; that we all can participate in it,” Bessye said in an unpublished oral history (conducted in October 1999 by Alice Bruno for the Connecticut Bar Foundation’s Women and the Connecticut Bar Oral History Project).

Bessye was a woman of many firsts. In 1974 she became the first African American woman to be hired to a corporate legal position in Hartford, where she rose from affirmative action officer at Society for Savings to associate counsel and assistant vice president of that company. “At the time you really had to work so hard to get your point across, and it really always didn’t seem fair,” she said in her 1999 oral history. In 1985 she established a solo private practice. She was the first African American woman appointed deputy town counsel for the Town of Bloomfield and the first to serve on the board of Connecticut Natural Gas. Throughout her legal career she also accepted pro bono legal cases and continued serving on the boards of such organizations as Connecticut Public Television, the Commission on Victim Services, the Knox Foundation, and Hartford College for Women.

In the words of activist and law professor Mari Matsuda, African American women live a “multiple consciousness” that allows them to operate within the mainstream and within their community, aware of their race, gender, and professional and private roles. Although many women live multiple lives, Matsuda’s point was the unique status of African American women who confronted discriminations of both race and gender while still maintaining a balance between their professional and private lives. Bessye Bennett was one of those trailblazing women: one who followed her dream of becoming a lawyer while still caring for family and community. “I had to confront my inner self, my inner dreams; not whine, not cry, but to keep going,” she said in her oral history. She died on May 16, 2000.

In 2002 I attended a ceremony at the University of Connecticut law school establishing the Bessye W. Bennett ’73 Memorial Scholarship Fund. Her husband John Bennett spoke about her life to me. Bessye loved her work, he told me, and she loved her family. “We had a partnership,” he said.

Constance Anita Belton Green is the former chief diversity officer at Eastern Connecticut State University. Green received the George W. Crawford Black Bar Association 2012 Trailblazer Award. She is the author of Still We Rise: African Americans at the University of Connecticut School of Law (University of Connecticut, 2019).

Explore!

“Site Lines: Constance Baker Motley’s Chester Retreat,” Summer 2021

Read more stories about the African American experience in Connecticut on our TOPICS page.

LISTEN to our podcast about the first women admitted to Yale University, including Constance Baker Motley’s niece, Constance Royster, episode 113: Yale Needs Women

Still We Rise: African Americans at the University of Connecticut School of Law