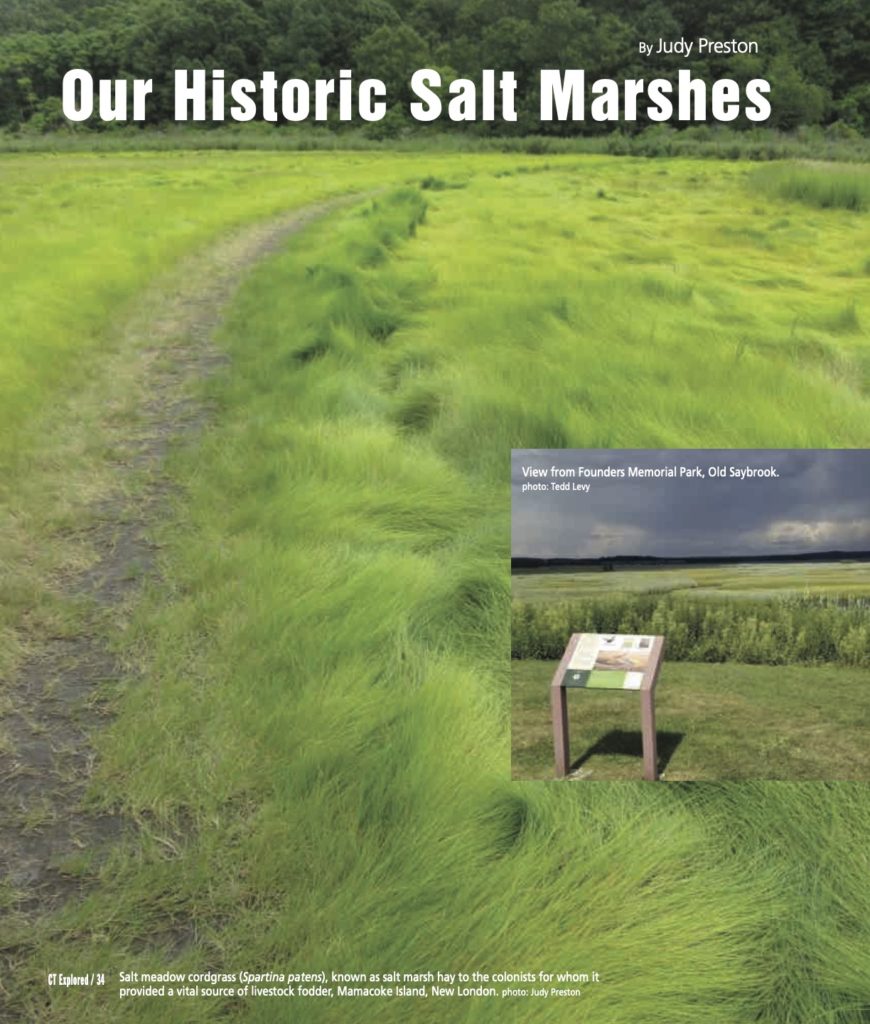

Salt meadow cordgrass (Spartina patens), known as salt marsh hay to the colonists for whom it provided a vital source of livestock fodder, Mamacoke Island, New London. photo: Judy Preston; inset: View from Founders Memorial Park, Old Saybrook. photo: Tedd Levy

By Judy Preston

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Spring 2021

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

In 2003 a new park called Founders Memorial Park was dedicated in the coastal town of Old Saybrook. With enough elevation to overlook the Connecticut River, broad expanses of tidal salt marshes, and Long Island Sound beyond, it may well offer the best view in the entire estuary region. Few know the story of how the site came to be: part of it sits atop an old town dump that had been built on the salt marsh. How coastal wetlands such as this have been valued through time is a part of our history and may well inform the future of these unique places.

A salt marsh is a remarkably resilient landscape, capable of withstanding inundation by salt water at high tide and exposure to the vagaries of the season, including harsh summer sun, winter ice, and the punishing forces of wind and waves at low tide. Salt marshes are defined by a relatively small but tenacious suite of plants that can withstand these conditions—fewer than 20 species in all. By contrast, tidal marshes farther inland and outside the influence of salt water can support more than 100 plant species. But salt marshes, which are built of successive seasons of spent organic material, fuel numerous food webs and make important contributions to the nutrients that make estuaries like Long Island Sound so productive.

Connecticut’s salt marshes today occupy approximately 15,000 acres, almost 30 percent less than in the 1880s, according to R. Scott Warren, et al., in “Salt Marsh Restoration in Connecticut: 20 Years of Science and Management,” Restoration Ecology (September 2002). As science has teased out the inner workings of this ecosystem, we increasingly realize the role salt marshes play in sustaining many wildlife populations, from economically important fisheries to some of the state’s largest concentrations of resident and migratory waterfowl.

Dominant among the handful of plants that can tolerate the conditions of a salt marsh are the grasses in the genus Spartina, which includes salt meadow cordgrass—the plant once familiarly known as salt marsh hay. This grass played a key role in sustaining early European colonists by enabling the widespread introduction of grazing livestock, which before colonial settlement were unknown to the New England landscape. Initially settlers had no source for hay to feed livestock, as Connecticut was then largely forested. Salt hay became a critical resource.

In the latter part of the 19th century, though, science identified mosquitoes, which thrive in marsh land, as disease vectors, and in 1895 Connecticut passed the Nuisance Arising from Swampy Places law. The legislation explicitly targeted marshes as a threat to human health.

Under President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal initiative, the Civilian Conservation Corps dug thousands of miles of narrow ditches, laid out in a grid pattern and spaced 100 to 150 feet apart, all along the eastern seaboard, with the intention of draining salt marshes to rid them of breeding mosquitoes. By 1940, 90 percent of coastal salt marshes on the Atlantic coast had been ditched, according to the Delaware Center for the Inland Bays. The legacy of this practice remains: I clearly remember the first time I saw these straight lines from a small plane, an alarming transgression on the otherwise sinuous inlets of Great Island in the Connecticut River estuary. Great Meadows Marsh at the mouth of the Housatonic River in Stratford is the largest, and one of the only, marshes in the state to have escaped being grid-ditched, though it is the subject of ongoing restoration due to industrial contamination from nearby industry.

The practice of ditching continued until the 1960s, when it fell out of favor because it was not entirely effective. Scientists were by then beginning to understand the practice’s long-term impacts on the salt marsh ecosystem. Connecticut passed legislation protecting coastal wetlands in 1969, following Massachusetts (1963) and Rhode Island (1965).

Salt marsh ditching, tide gates (used to restrict tidal flooding), and insecticide spraying continued to be used to control mosquitoes in Connecticut marshes until 1985. By then a more nuanced technique was adopted. Shallow depressions are created on the highest marsh surfaces, connected by barely perceptible and elevation-dependent channels that permit periodic high and storm tides to flood these features. In with the tidal waters come several species of killifish, small fish that are effective predators of mosquito larvae. By generating fish habitat, this technique also attracts the shorebirds, including waders such as egrets, herons, and other waterfowl to these water features, making them productive and lively features on the marsh surface. This method, known as open marsh water management, represents a considerable improvement over historic efforts to control mosquitos.

The Connecticut coast, because of its location, weather, and geography, is particularly at risk for sea-level rise, a circumstance that puts both the low-elevation salt marsh and coastal residents at risk. How we respond to this—informed by a historical perspective—could make all the difference for both.

Judy Preston is an ecologist who has worked in nonprofit conservation for many years.

Explore!

Founders Memorial Park

100 Coulter Street, Old Saybrook

Great Meadows Marsh Unit, Stewart B. McKinney National Wildlife Refuge

Long Beach Boulevard, Stratford

fws.gov/refuge/Stewart_B_McKinney/

See related story, page 32.