SoHldier’s

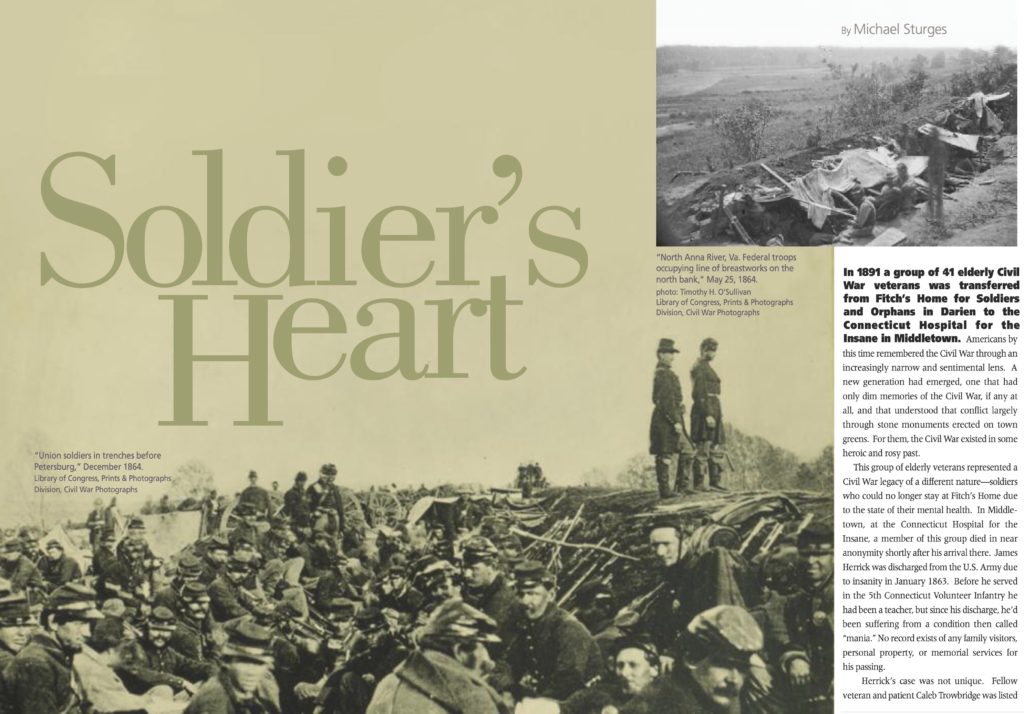

“Union soldiers in trenches before Petersburg,” December 1864. Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, Civil War Photographs; inset: North Anna River, Va. Federal troops occupying line of breastworks on the north bank,” May 25, 1864. photo: Timothy H. O’Sullivan Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, Civil War Photographs

By Michael Sturges

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Spring 2011

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

In 1891 a group of 41 elderly Civil War veterans was transferred from Fitch’s Home for Soldiers and Orphans in Darien to the Connecticut Hospital for the Insane in Middletown. Americans by this time remembered the Civil War through an increasingly narrow and sentimental lens. A new generation had emerged, one that had only dim memories of the Civil War, if any at all, and that understood that conflict largely through stone monuments erected on town greens. For them, the Civil War existed in some heroic and rosy past.

This group of elderly veterans represented a Civil War legacy of a different nature—soldiers who could no longer stay at Fitch’s Home due to the state of their mental health. In Middletown, at the Connecticut Hospital for the Insane, a member of this group died in near anonymity shortly after his arrival there. James Herrick was discharged from the U.S. Army due to insanity in January 1863. Before he served in the 5th Connecticut Volunteer Infantry he had been a teacher, but since his discharge, he’d been suffering from a condition then called “mania.” No record exists of any family visitors, personal property, or memorial services for his passing.

Herrick’s case was not unique. Fellow veteran and patient Caleb Trowbridge was listed in the records of more than one institution as an “inebriate.” He had been expelled from Fitch’s Home and sent home but was subsequently readmitted nine times for alcohol and opium possession. He apparently also had a violent disposition toward staff. During the periods when he was home, Trowbridge was arrested four times and returned to Fitch’s after each arrest, presumably unfit for life outside. Both Herrick and Trowbridge represent a population of Connecticut Civil War veterans who have been largely edited out of the shared memory of the Civil War.

Assessing the toll of the Civil War on veterans’ mental health is a relatively new area of study, pioneered by Eric T. Dean, Jr. in Shook Over Hell: Post-Traumatic Stress, Vietnam, and the Civil War (Harvard University Press, 1997) and in the recent HBO documentary Wartorn: 1861-2010. In Connecticut, we know that Trowbridge and Herrick were not the state’s only troubled Civil War veterans. The extent to which their mental illness—and that of an unknown number of other veterans—was understood by the doctors who treated them is yet to be fully determined.

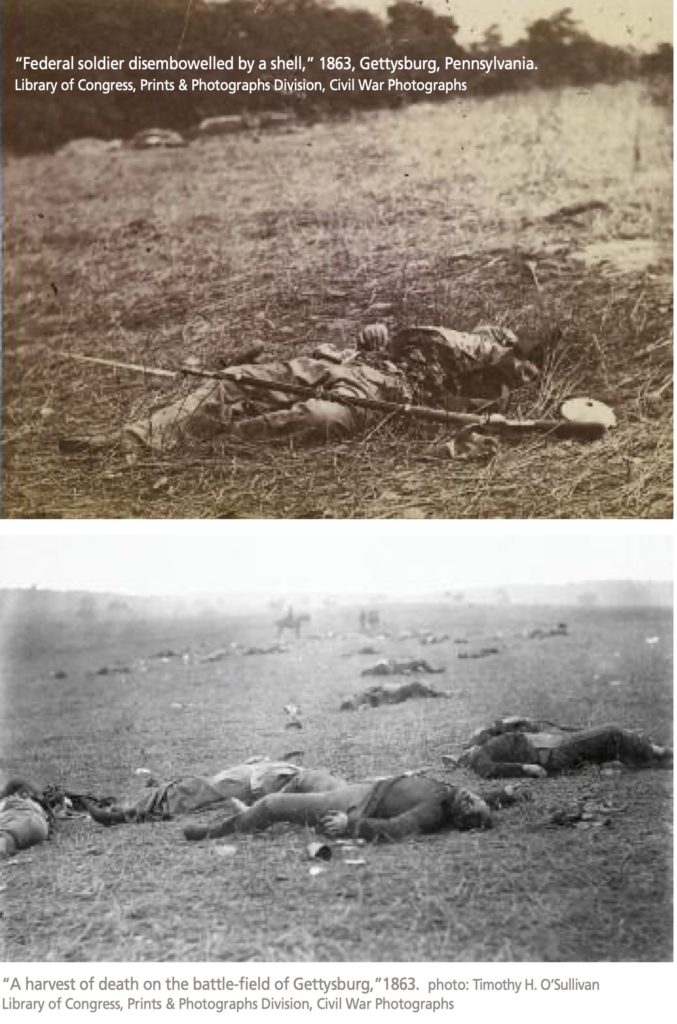

top: “Federal soldier disembowelled by a shell,” 1863, Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, Civil War Photographs; bottom: “A harvest of death on the battle-field of Gettysburg,” 1863. photo: Timothy H. O’Sullivan Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, Civil War Photographs

This piece is the product of research conducted in the fall of 2008 for a graduate course at Central Connecticut State University. The purpose of the project was to investigate what records are available in Connecticut relating to the psychological casualties of the Civil War and to attempt an educated guess as to how many Civil War veterans in the state suffered long after the shooting stopped. The documentary record includes information about who received disability pensions in the state, where these men were housed, what diagnoses they received, and what proportion of their lives were spent in institutional care. For example, in 1880, the State of Connecticut supplemented its decennial census with a special “Census of Defective, Dependant, and Delinquent Persons.” The census takers who visited the Connecticut Hospital for the Insane took note of when the patients had entered the facility, when they first had suffered the current “attack” that brought them to the institution, and a general diagnosis. Records such as these can be cross-referenced with pension records provided by the federal or state government, which also state the injury or ailment that entitled the veteran to a pension. This project focused on such ailments as “nervous disease,” “nervous irritability,” and “insanity.”

Before modern psychology shed light on the workings of the human mind, insanity was attributed to physical damage to the brain, an imbalance of the body’s systems, moral deficiency, or intemperate behavior. Society did not recognize as we do today that experiences of trauma, independent of physical wounds, can cause psychological damage.

With the advent of modern medicine and deeper understanding of the human brain, today we understand that soldiers returning from war can bear psychological scars that require care. In World War I, the condition was called “shell shock,” in World War II “combat exhaustion,” in the Korea War “battle fatigue.” Though the condition was little understood at the time, it had its own name during the Civil War: “Soldier’s Heart.” In the aftermath of the Vietnam War, though, our knowledge of the impact of the trauma of war grew exponentially, and the phenomenon received a new name, complete with a modern psychological pathology and a set of treatments: Post Traumatic Stress Disorder or PTSD. As a result of that recognition, soldiers coming home from Iraq or Afghanistan who experience persistent symptoms of mental trauma receive more support for and recognition of their psychological wounds than have any previous Americans (though some would argue that they still do not receive the full measure of help they need).

When the concept of PTSD first emerged, many observers believed that the Vietnam War, by its very nature, had produced far more psychological casualties than other American wars. The terror of jungle warfare, the isolation of soldiers in combat, and the intense fear of death from a hidden and seemingly merciless enemy were believed to have placed greater emotional strain on soldiers than the more straightforward stresses of earlier conflicts. One of the earliest and most common theories explaining Vietnam veterans’ plight was rooted in politics: It posited that the moral dilemma posed by America’s conduct of the war, and the war’s ambiguous outcome, contributed to the unappreciative manner in which returning veterans were received at home. The corresponding lack of the kind of nationalism and societal gratitude—and relief—that had followed World War II, the argument went, left Vietnam vets with no perspective on their sacrifice, no positive reinforcement to balance the equation of their experience.

We now see that psychological combat disorders (of which PTSD is the most widely known) have resulted from every U.S. war. So what does that mean for the men who fought in the nation’s most traumatic conflict—the Civil War? That war’s death toll of 620,000 exceeds the losses from every other American war combined. The battle at Antietam saw twice as many men die or suffer injury in one day than the combined death toll from the War of 1812, the Mexican War, and the Spanish-American War, and four times more than at the Normandy beaches on D-Day.

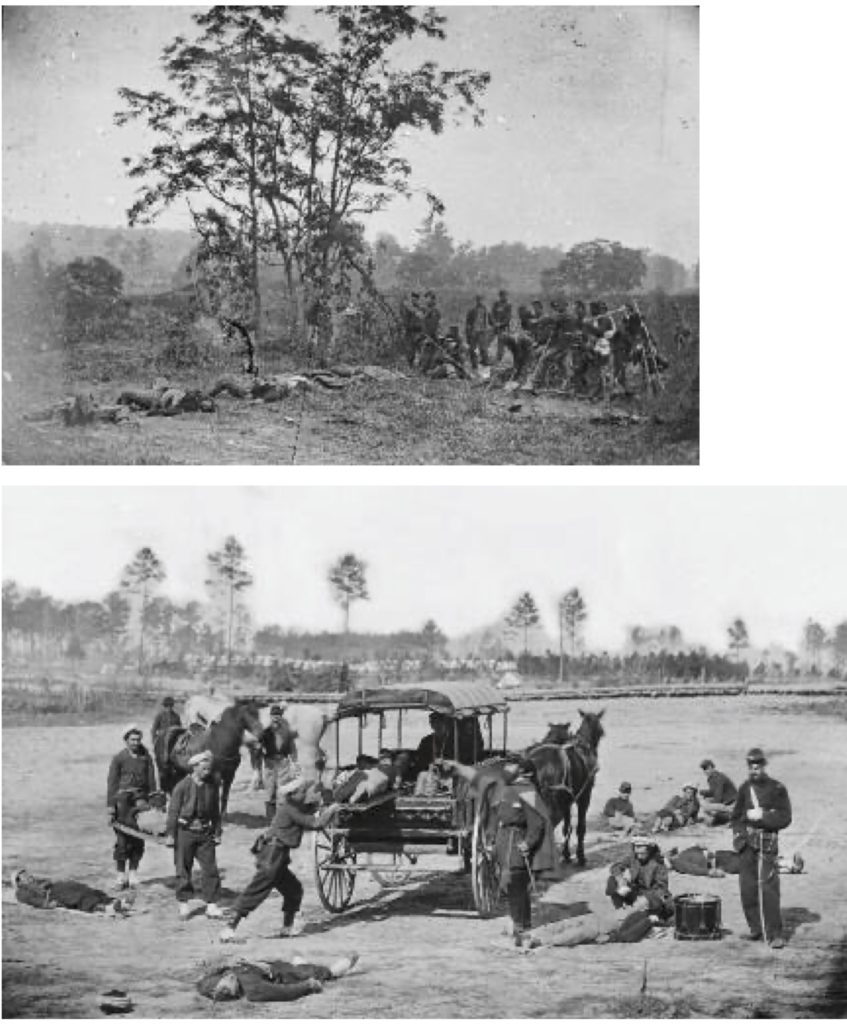

top: Antietam, Maryland. Burying the dead Confederate soldiers,” September 1862. photo: Alexander Gardner

Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, Civil War Photographs; bottom: “Zouave ambulance crew demonstrating removal of wounded soldiers from the field,” location unknown, c.1860s.

Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, Civil War Photographs

But numbers alone do not tell the story. As Dean notes in Shook Over Hell, “of the field at Shiloh, a Hoosier noted that dead men seemed to be everywhere: ‘You could find them in every hollow, by every tree stump—in open field and under copse—Union and Rebel, side by side….’ The psychological effect of these scenes could be devastating.” The carnage was great, as was the deprivation of a soldier’s life. The hundreds of miles marched by the average foot soldier, the primitive conditions in camp, and the poor food in short supply were just prelude to the terror of brutal pitched battles in which atrocities were committed by both sides, villages were burned and pillaged, and days capped by gruesome burial details.

Research is making it increasingly evident that what we now call PTSD existed and was a factor in the lives of perhaps thousands of veterans in the aftermath of the Civil War. To date, however, no nationwide attempt has been made to measure the impact of psychological wounds on the Civil War generation. But portions of the bigger picture are beginning to be uncovered at the state level, including findings here in Connecticut.

For several reasons, it’s hard to piece together an understanding of Connecticut’s experience with the psychological wounds of its Civil War veterans. First, it’s difficult to apply 20th-century medical concepts to 19th-century understanding. Many symptoms now associated with combat-related psychological trauma were not recognized or measured during the late 19th century. Some symptoms now recognized as associated with PTSD such as dissociation, depression, hyper-vigilance, and an increased sensitivity to certain stimuli (such as narrow spaces or fireworks) might in the late 19th century have been lumped into one of three large and vague categories: mania, melancholia, and dementia. Some symptoms may not have been recorded at all, while others may have been described in unfamiliar terms. A good example is “nostalgia,” a term that could be used variously to mean depression or flashbacks. At times patients would be referred to as stricken or suffering from severe nostalgia. To conduct an investigation of Civil War veterans today requires considerable translation of 19th-century psychological diagnoses into those that a modern professional would use to diagnose PTSD.

Despite these difficulties, it’s very clear that there was a population of Civil War Connecticut veterans who suffered from psychological ailments. In 1883, the state of Connecticut commissioned a census of its disabled veteran pensioners. The data included the veterans’ names, their date of injury, the disability that caused the pension to be awarded, and the monthly payment each pensioner received. This document is an excellent starting point because it establishes several interesting facts regarding the psychological casualties in Connecticut. The census shows that there were between 10 and 65 Connecticut veterans receiving federal pensions exclusively for military-service-related conditions that are now associated with PTSD. A liberal interpretation, which includes all possible conditions we now relate to PTSD, would find that 65 veterans in Connecticut suffered varying degrees of psychological combat-related trauma including “nervous diseases,” alternately listed as “nervous agitation,” “nervous exhaustion,” “neurasthenia” (a 19th-century name for depression or anxiety), or simply “nervous disorder” (which particular malady affected 55 of the soldiers listed). If we accept, then, that 65 of the veterans listed in the state’s census suffered from some form of mental disability that we now associate with PTSD, that number amounts to nearly 1 percent of the more than 7,000 disabled veterans listed.

Even the most conservative reading of the document suggests that at least eight of the pensioners were suffering from psychological disorders caused by their war experiences and that their suffering was severe. Six of the men had “insanity” listed as their sole disability. That “insanity” is listed as the reason for their receiving pensions is clear evidence that the U.S. government recognized that these men became disabled as a result of their war experiences, since the Pension act of 1862 required that the disability warranting compensation be sustained during the war. It is also interesting to note that veterans with insanity diagnoses received pension payments comparable to those awarded veterans who had lost limbs or eyes. Four of the six “insane” veterans received $50 a month, the same amount given to men who had lost either both legs or their dominant arm. The other two received $72 a month, the same amount as soldiers who had lost both eyes or both arms.

But with no accepted concept of psychogenic trauma (psychological damage caused by experience and not necessarily connected to any physical damage) there was no standardized vocabulary to accurately express the war-wrought changes observed in the soldier. It is therefore much harder to estimate how many genuinely suffered from psychological wounds but were turned away from pension offices. This population, for whom the only existing documentation is pension rejection records, can only be studied in an indirect manner.

There is, however, another valuable source of evidence that indirectly suggests PTSD in Civil War veterans. Whether pensioned or not, veterans who were disabled or lacked the means to support themselves did have a place to go: Fitch’s Home in Noroton Heights (Darien), which was the first soldiers’ home in the nation. In the records of Fitch’s and its successor organization, the Connecticut Veteran’s Home, alcohol and opium abuse were rampant. Although alcoholism and opium abuse, the two most common forms of substance abuse in the late 1800s, were by no means evidence of PTSD on their own, they would today be associated symptoms that co-occur frequently with PTSD.

In some cases the substance abuse was severe enough to result in the discharge of the veteran from the home. (Alcoholism as a disease was also not recognized at this time). Discharge records for Fitch’s Home show that between 1870 and 1900, 60 veterans were discharged involuntarily for possession of alcohol (23), drunkenness (16), alcoholism (15), or possession of opium (6). The men had multiple transgressions and received repeated warnings before being discharged and turned out to fend for themselves. It’s hard to know what to make of these numbers, though, as alcohol abuse and opium and morphine addiction were commonplace in the mid 19th-century. Such substances were widely used as painkillers by veterans and civilians alike before the advent of modern anesthesia.

“The Battle Story (The Returned Soldier),” Larkin Goldsmith Mead, c. 1860s. Originally on the grounds of Fitch’s Home for Soldiers and Orphans, now on the grounds of the Connecticut Veterans’ Home, Rocky Hill. photo: Connecticut Department of Veterans’s Affairs

Similar evidence appears in the historical roster of the Connecticut Soldier’s Home (Fitch’s Home). It records 493 residents, lists their infirmities, and for many includes physicians’ notes about special requirements for their care. Twenty-nine residents (6 percent) are listed as suffering from now-PTSD-related symptoms similar to those listed above. A second soldiers’ home housing Connecticut veterans was the National Soldiers’ Home, Central Branch in Dayton, Ohio. The records from this home are consistent with the Connecticut records regarding the incidence of substance abuse. Of the 128 soldiers from Connecticut living in the Dayton facility, 10 were involuntarily discharged for substance abuse issues, and 4 of those were also cited for violent behavior.

Further evidence of Connecticut’s psychological casualties are found in records from facilities that housed and treated the mentally ill including but not limited to veterans, such as The Connecticut Hospital for the Insane (today Connecticut Valley Hospital) in Middletown and The Hartford Retreat for the Insane (today the Institute of Living) in Hartford. In 1891, 41 veterans were transferred from Fitch’s Home to the Connecticut Hospital for the Insane. All of the patients transferred suffered from now-PTSD-related conditions: 11 from alcoholism, 5 from inebriety (a term used for intoxication apart from alcohol; most likely opium), 5 from mental paralysis, 6 from imbecility (which in the case of men who passed muster for the Union Army most likely meant some severe type of dissociative disorder, which would explain incoherence or non-responsiveness apart from mental paralysis or dementia), 4 from dementia, 8 from mania, 7 from neurasthenia, and 1 from intemperance (likely extreme irritability, given the presence of alcoholism and inebriety as separate categories). This would indicate that groups of veterans suffering from psychological wounds manifested their illness in a variety of ways, and that caregivers of the time thought their symptoms serious enough to consider them best suited for an insane asylum. Eventually, 37 of these veterans died in the asylum.

The above statistics represent only those veterans who sought or were given institutional care at the expense of either the state or federal government and who represented some of the most extreme cases. They omit any who suffered silently and alone, perhaps out of shame or fearing pity. Americans held very different views about mental illness in the 19th century, and the stigma attached to having an insane family member may have also kept many suffering veterans under the care of family members and out of official records. What little record there is provides us with an incomplete understanding of psychological casualties of the Civil War in Connecticut, though one from which an increasingly clear picture is developing. Given the military’s growing attention to brain disorders and PTSD caused by combat experiences among Iraq and Afghanistan veterans, along with rising social sensitivity to the nature and history of the phenomenon spurred by HBO’s documentary on the topic and by the work of historians such as Eric Dean, Connecticut’s story promises to become increasingly intriguing.

Note: In 2009, Michael Sturges and Dr. Matthew Warshauer filed a Freedom of Information request with the Connecticut Freedom of Information Commission to gain access to the Civil War patient records housed at Connecticut Valley Hospital. Access to these records had been denied on grounds that permitting researchers to view medical files on Civil War veterans constituted a breach of doctor/patient confidentiality. The Commission disagreed, and the records were turned over to the Connecticut State Library.

Michael Sturges is a graduate student at Central Connecticut State University and a social studies teacher at Nonnewaug High School in Woodbury, Connecticut.

Explore!

Read more about Connecticut in the Civil War

Spring 2011

Winter 2012/2013

On our Connecticut in the Civil War TOPICS page

On our War Stories TOPICS page