By Yohuru Williams

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Winter 2019-2020

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

In the summer of 1970 the people of New Haven, Connecticut braced for the start of what local journalists billed as the trial of the century, the legal proceedings against members of the New Haven chapter of the Black Panther Party for the murder of a 24-year-old New York Panther named Alex Rackley. The murder and trial shifted attention away from efforts by the Panthers and a host of other local civil rights and Black Power organizations to address issues of economic and political equality in the city of New Haven.

Founded in Oakland, California in 1966 by Huey Newton and Bobby Seale, the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense soon emerged as a national organization. The founders drafted a 10-point program that laid out the party’s basic aims, ready-made for export beyond Oakland. Consistent with point number 5, which called for an end to police brutality, the Panthers also began armed patrols monitoring police.

After several high-profile confrontations with police, including the incarceration of Party co-founder Huey Newton for the shooting of an Oakland police officer in 1967, in 1968 the Party dropped self-defense from its name and embarked on a series of “Serve the People” initiatives designed to soften its image and highlight its community-service programs. The change in focus did little to deflect law enforcement’s interest in the party, most notably at the Federal Bureau of Investigation. FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover would, in March 1968, refer to the Panthers as “the single greatest threat to the internal security” of the United States.

Fear and paranoia within the Panther organization led to efforts to ferret out suspected police informants, often with tragic consequences. In New York, national Panther “Field Marshal” George Sams Jr. recruited local Party-member and Florida native Alex Rackley to accompany him on an inspection visit to New Haven. In New Haven Sams accused Rackley of providing information to New York City police about New York Panthers accused in a bombing plot against the city. Over the next three days, the New Haven Panthers tortured Rackley in the hopes of extracting a confession, resulting in his murder. Sams ordered the titular head of the New Haven Party, Ericka Huggins, to tape the interrogation for national headquarters.

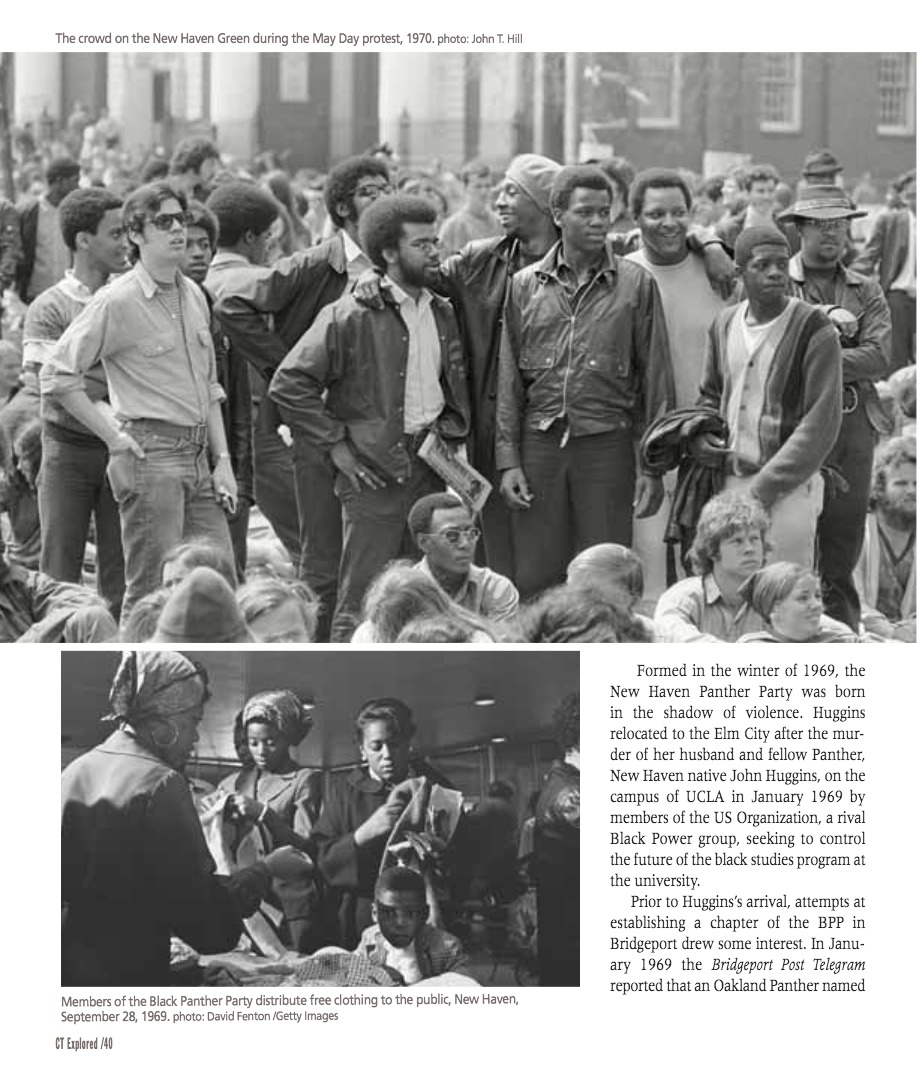

Formed in the winter of 1969, the New Haven Panther Party was born in the shadow of violence. Huggins relocated to the Elm City following the murder of her husband and fellow Panther, New Haven native Jon Huggins, on the campus of UCLA in January 1969 by members of the US organization, a rival Black Power group, seeking to control the future of the Black Studies program at the university.

Formed in the winter of 1969, the New Haven Panther Party was born in the shadow of violence. Huggins relocated to the Elm City following the murder of her husband and fellow Panther, New Haven native Jon Huggins, on the campus of UCLA in January 1969 by members of the US organization, a rival Black Power group, seeking to control the future of the Black Studies program at the university.

Prior to Huggins’s arrival, attempts at establishing a chapter of the BPP in Bridgeport drew some interest. In January 1969, the Bridgeport Post Telegram reported that an Oakland Panther named Jose Gonzalez had organized a chapter of the Party in that city. With Huggins’s arrival, a majority of the would-be Panthers in Bridgeport merged with similarly interested recruits in New Haven and went to work implementing the BPP’s programs in earnest. Selling the party newspaper, community service work, and political education classes occupied most of their time. Although the national offices would later claim that Huggins was the only acknowledged Panther in New Haven, the Party made strong inroads recruiting a small cadre of activists amplified by dozens of volunteers who helped staff the Panthers’ programs and who also regularly attended political-education classes.

The Panthers’ community work furthered the efforts of earlier Black Power organizations in the city such as the Hill Parents Association (HPA), which had also focused on community service initiatives as the key to improving the condition of blacks and Latinos within the city. After a riot took place in the city in the summer of 1967, the Hill Parents Association was virtually driven out of existence by a campaign of police harassment, leaving a void that the BPP would later help to fill.

Like the HPA, the New Haven BPP would also be the subject of intense scrutiny by local, state, and federal law enforcement. In areas where the BPP was active, the FBI, along with various state and local law enforcement agencies, had been closely monitoring the activities of the Party and had been recruiting informants to infiltrate its ranks. The FBI seized upon these efforts as part of its counterintelligence program that targeted groups like the Panthers whom FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover labeled as “Black Nationalists and Hate type organizations.” Unfortunately for all parties in New Haven, these efforts would have tragic results.

Like the HPA, the New Haven BPP would also be the subject of intense scrutiny by local, state, and federal law enforcement. In areas where the BPP was active, the FBI, along with various state and local law enforcement agencies, had been closely monitoring the activities of the Party and had been recruiting informants to infiltrate its ranks. The FBI seized upon these efforts as part of its counterintelligence program that targeted groups like the Panthers whom FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover labeled as “Black Nationalists and Hate type organizations.” Unfortunately for all parties in New Haven, these efforts would have tragic results.

Among those arrested for the Rackley murder were New Haven Panther recruits Warren Kimbro and Lonnie McLucas. New Haven Prosecutor Arnold Markle also sought to implicate Ericka Huggins and national Party chairperson Bobby Seale, claiming that the Panthers executed Rackley on Seale’s orders. Kimbro, who had been one of the local Party’s dedicated organizers, turned state’s evidence and agreed to testify against the Panthers. He joined Sams, who claimed he had orchestrated the torture of Rackley at Seale’s behest, as one of the prosecution’s star witnesses. The state elected to try McLucas first. Jury selection began in May 1970 against the backdrop of growing national interest in the case.

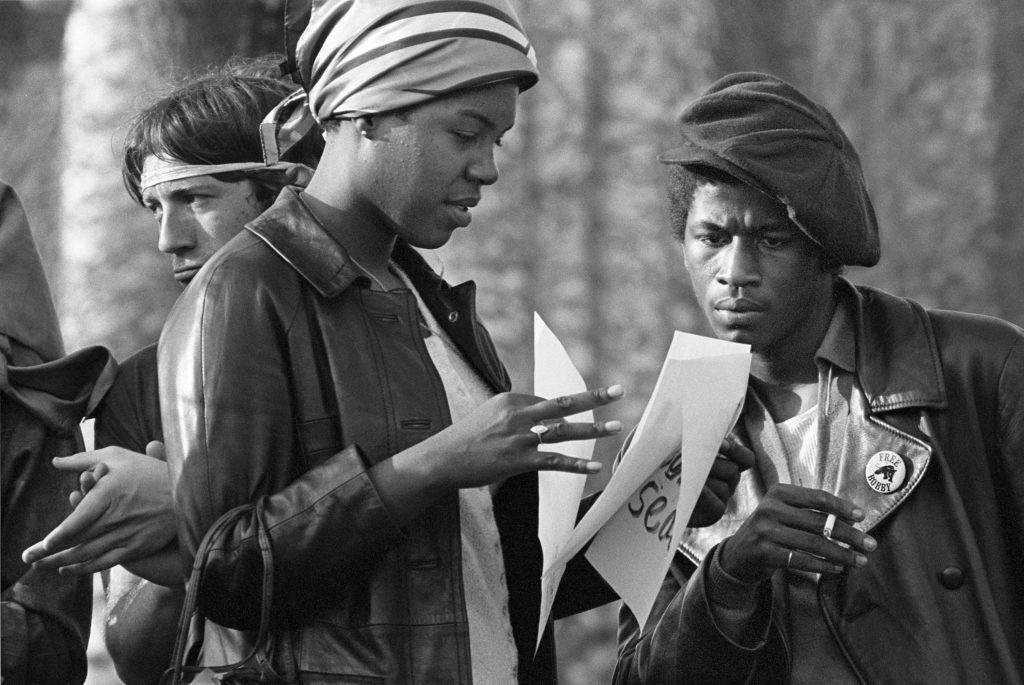

“Artie” Seale, wife of BPP co-founder Bobby Seale, and Michael Tabor, a captain in the New York branch of the BPP, May Day, New Haven, 1970. Photo: John T. Hill

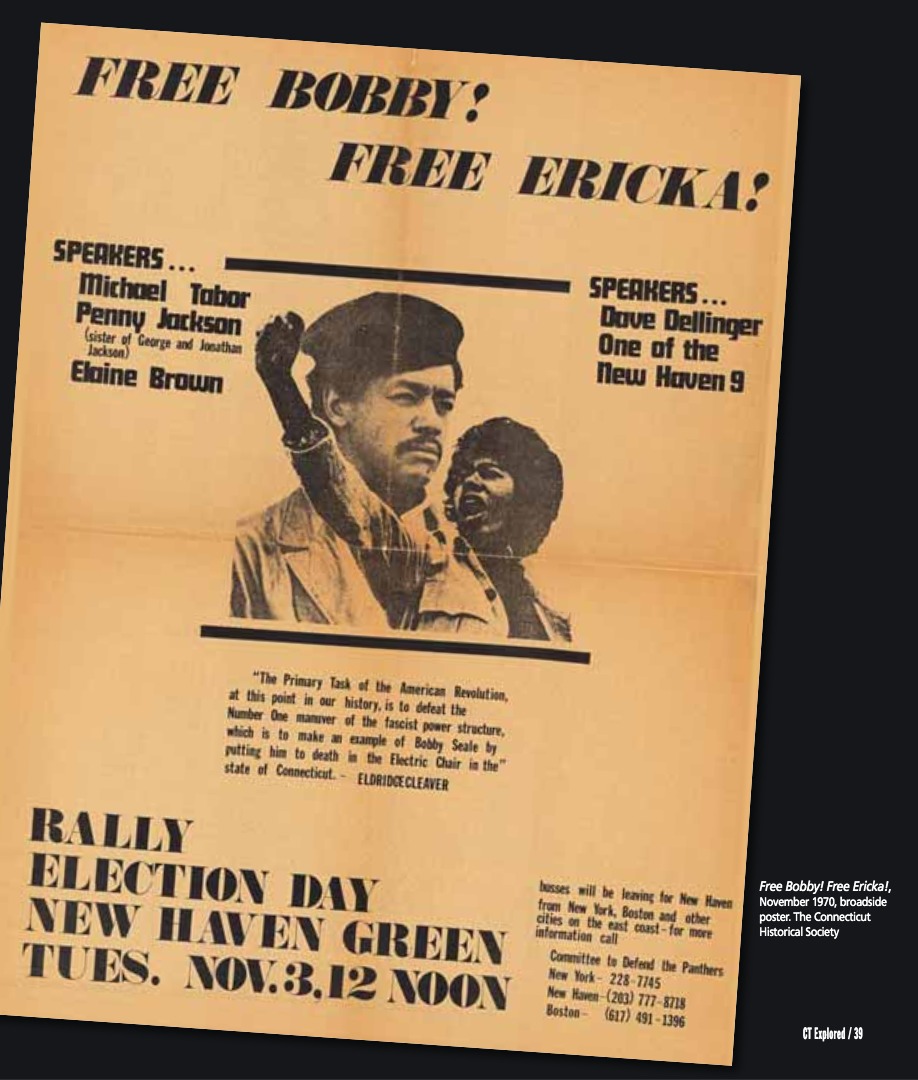

Capitalizing on this interest, and in an effort to help pay for the defense of those accused, the BPP disclosed plans for a three-day fundraising campaign on the New Haven Green set to commence on May Day. In an effort to drum up support, the BPP invited a slate of nationally recognized speakers to appear, including Youth International Party leader Abbie Hoffman and anti-war activist Dr. Benjamin Spock. Panther supporters planned to descend on the Elm City on May Day weekend to protest the impending trial. Fearing the potential for violence and stoked to a certain extent by the rhetoric of activists like Hoffman, who claimed the protesters’ intent would be to “Free Bobby” and “burn Yale,” and Panther Chief of Staff David Hilliard, who made similar statements, state and local authorities teamed with federal law enforcement to prepare for battle.

In advance of reports that anticipated anywhere from 50,000 to 500,000 demonstrators, Connecticut Governor John Dempsey mobilized the Connecticut National Guard, while U.S Attorney General John Mitchell asked the Pentagon to deploy 4,000 Marines and Army paratroopers to armories on the outskirts of the city, The New York Times reported April 30, 1970. Yale University President Kingman Brewster publicly expressed reservations that a Black revolutionary could receive a fair trial in the United States. While encouraging faculty to cancel classes, he also kept the university open as a resource to house and feed protesters. Aside from a few minor skirmishes, however, the protests remained peaceful even as radical students, antiwar protesters, and a variety of other activists swelled the ranks of the Panthers’ supporters.

During the McLucas trial that began in July, Kimbro and Sams emerged as the state’s star witnesses. Neither proved especially convincing on the stand, though. Kimbro acknowledged that he had fired the fatal shot that killed Rackley after Sams handed him a gun telling him that orders had come down from national to “ice” Rackley. While both testified that McLucas fired a safety shot into Rackley’s chest to finish the job, neither could establish McLucas’s culpability for the murder. After the trial closed in early August, the jury took several days to acquit McLucas on all charges except conspiracy to kill, which earned him a 12-year sentence.

When the second Rackley murder trial—with Ericka Huggins and Bobby Seale as co-defendants—commenced in October 1970, the tide had turned in the Panthers’ favor. The prosecution’s lackluster performance in the first trial pointed to a similar outcome in the Seale and Huggins proceedings. Huggins and Seale were also favored with a strong legal team. Catherine Roraback, a Connecticut civil rights attorney best known for arguing the 1965 U.S. Supreme Court case that legalized the use of birth control in Connecticut [See “Connecticut Women Fight for Reproductive Rights,” Fall 2017], represented Huggins. Charles Garry, Huey Newton’s attorney from his 1967 trial for murder in connection with slaying an Oakland, California policeman, represented Seale. The seasoned barristers were accustomed to taking on radical causes and were able to mount a successful defense based on the state’s weak evidence. Prosecutor Markle, in the meantime, struggled to produce witnesses other than Sams who would testify that Seale gave the order to kill Rackley.

Given the immense publicity generated by the legal proceedings and the May Day protests, seating an impartial jury took four months. The case against Huggins and Seale was porous. The narrative of events established by the witnesses, including the prosecution’s own, contradicted the state’s case. Kimbro, who testified first, proved unable to tie Huggins to the shooting and acknowledged that he had never seen Seale at the Panther headquarters, as Sams had alleged. The defense, in the meantime, was able to call into question not only Sams’s veracity, but also his mental health. Garry was able to show that Seale had expelled Sams, a diagnosed mental patient with a long history of violence, from the Party for beating up several members. In spite of his expulsion, and underscoring the organizational shortcomings of the national Black Panther Party, Sams was still able to pass himself off as a Panther field marshall. Shortly before Seale’s scheduled arrival in New Haven to deliver a speech at Yale’s Battell Chapel on May 19, 1969, Sams and several other emissaries from the national offices showed up on the inspection visit. Testimony for both sides clearly illustrated that Sams initiated the torture of Rackley and that he ordered it recorded on tape for national headquarters. More importantly, only Sams testified to Seale’s alleged directive to kill Rackley.

Prosecutor Markle’s attempt to call a New Haven police detective to the stand to support Sams’s claim that Seale had entered the headquarters backfired when a diagram displaying where the detective had been parked on the night in question disputed his testimony. The prosecution finally rested in late April. The case went to the jury on May 29. After five days of intense deliberation, the jury reported that it was hopelessly deadlocked 11 to 1 in favor of an acquittal for Seale, and 10 to 2 in favor of an acquittal for Huggins.

As Lonnie McLucas’s counsel Michael Koskoff conceptualized the problem, the prosecution’s downfall was its attempt to implicate Seale. “They already had a confession from two shooters,” Koskoff explained. “They could do no better than that. [State’s Attorney] Markle … got sucked in by the politics.” Citing the prejudicial nature of the publicity generated by both trials, on May 25 Judge Harold Mulvey dismissed the charges against Huggins and Seale. “I find it impossible to believe,” he explained in issuing his ruling, “that an unbiased jury could be selected without superhuman efforts—efforts which this court, the state, and these defendants should not be called upon to either to make or to endure,” the Eugene (Oregon) Register-Guard reported on May 26, 1971.

Although the trial ultimately ended in acquittals, the legacy of the New Haven trials is mixed. The trial revealed the vast array of law enforcement techniques and resources used against the Panthers, from paid informants to illegal electronic surveillance.

While the New Haven police force was celebrated for keeping New Haven calm during May Day, it was later discovered, for example, that the police had extensive wiretaps on the Panther headquarters in violation of state and federal law. Moreover, the New Haven police may have failed to act to prevent the Rackley murder and facilitated the transport of Rackley to the place of his execution via the use of a paid informant’s car in the hopes of making a strong case against the Panthers. In the early 1980s the city settled a massive lawsuit with the victims of the wiretaps, including several members of the Black Panther Party.

The legacy of the trial for the Panthers is also mixed. The trial brought national attention to New Haven, and the Panthers committed resources to make New Haven a model chapter, implementing a range of community-service programs, including a free health clinic that endured beyond the Panthers’ stay. While in prison awaiting their trials, both Seale and Huggins brought awareness to prisoner abuses. Seale organized prisoners at the Montville jail, where he threatened a hunger strike to bring attention to the treatment of those incarcerated there. Huggins likewise used her time in prison to highlight the treatment of female prisoners, especially mothers. Nevertheless, the trial also exposed the problems inherent in the Party’s organizational structure and the willingness, even if prodded by informants and agent provocateurs, of members to kill, even one of their own, in the name of advancing their revolutionary aims.

The Party’s links with such acts further hurt it in the public eye and provided many opportunities for law enforcement to justify its campaign of harassment that continued to bear deadly fruit. The FBI hunt for George Sams in connection with the Rackley murder, for instance, had set off a series of confrontations between police and the Black Panthers in Chicago that culminated in the December 4, 1969 pre-dawn raid on Party headquarters there. That raid resulted in the police killings of Chicago BPP leaders Fred Hampton and Mark Clark. Police were able to execute the raid with a floor plan of the apartment where the Panthers were staying, drawn by Chicago BPP Minister of Defense William O’Neal, a paid informant with the FBI.

The reverberations of the Panther trials within New Haven also had significant impact. The city briefly captured the national spotlight as the epicenter of radical protest. George Sams, Warren Kimbro, and Lonnie McLucas received sentences for their roles in the murder of Alex Rackley. After pleading guilty to second-degree murder and agreeing to turn state’s evidence, Kimbro ultimately served four years of a life sentence, earning time off for exemplary behavior. He dedicated the rest of his life to trying to make a difference through community-outreach initiatives. Also paroled after four years, Sams has been in and out of prison for a variety of charges. Granted release on an appeal bond in 1974, McLucas served the longest sentence of all those convicted. With the threat of having his bail revoked in 1977, he refused to denounce his work with the Party. He nevertheless told reporters, “But I deeply regret those three days” the South Mississippi Sun reported on October 12, 1977.

On the positive side, the activities surrounding the trials demonstrated the organizing capabilities of the Panthers and the party’s ability to inspire radical change. They also illustrated how the quest for Black Power need not exclude white supporters, as black and white activists joined together in a variety of initiatives inspired by the Panther trials to address political inequality, health care, and prisoners’ rights issues.

Yohuru Williams is the author of Black Politics/White Power: Civil Rights, Black Power, and the Black Panthers in New Haven (Blackwell Press, 2000). This story first appeared in African American Connecticut Explored (Wesleyan University Press, 2014).

Explore!

“The Hartford Chapter of the Black Panthers: Interview with Butch Lewis,” Fall 2004

Read all of our stories about the African American experience in Connecticut on our TOPICS page.