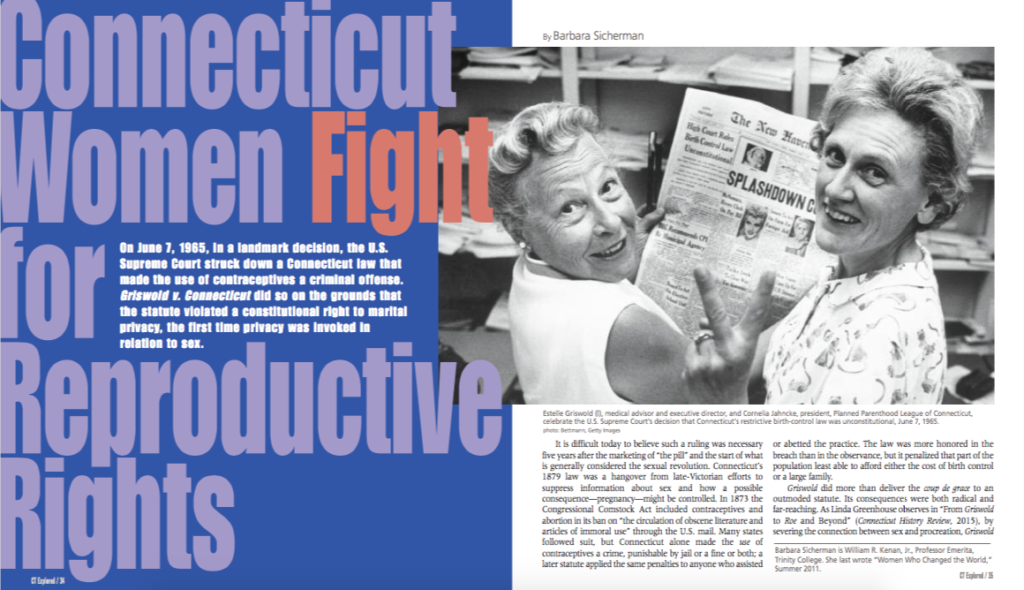

Estelle Griswold (l), medical advisor and executive director, and Cornelia Jahncke, president, Planned Parenthood League of Connecticut, celebrate the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision that Connecticut’s restrictive birth-control law was unconstitutional, June 7, 1965. photo: Bettman, Getty Images

By Barbara Sicherman

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc., Fall 2017

On June 7, 1965, in a landmark decision, the U.S. Supreme Court struck down a Connecticut law that made the use of contraceptives a criminal offense. Griswold v. Connecticut did so on the grounds that the statute violated a constitutional right to marital privacy, the first time privacy was invoked in relation to sex.

It is difficult today to believe such a ruling was necessary five years after the marketing of “the pill” and the start of what is generally considered the sexual revolution. Connecticut’s 1879 law was a hangover from late-Victorian efforts to suppress information about sex and how a possible consequence–-pregnancy-–might be controlled. In 1873 the Congressional Comstock Act included contraceptives and abortion in its ban on “the circulation of obscene literature and articles of immoral use” through the U.S. mail. Many states followed suit, but Connecticut alone made the use of contraceptives a crime, punishable by jail or a fine or both; a later statute applied the same penalties to anyone who assisted or abetted the practice. The law was more honored in the breach than in the observance, but it penalized that part of the population least able to afford either the cost of birth control or a large family.

Griswold did more than deliver the coup de grace to an outmoded statute. Its consequences were both radical and far-reaching. As Linda Greenhouse observes in “From Griswold to Roe and Beyond” (Connecticut History Review, 2015), by severing the connection between sex and procreation, Griswold paved the way for decisions that guaranteed constitutional rights to abortion (Roe v. Wade, 1973) and same-sex marriage (Obergefell v. Hodges, 2015). These decisions collectively limited the state’s role as moral police in matters pertaining to sex and reproduction.

By gaining the right to control their fertility, women were primary beneficiaries of the new freedoms. Their freedoms were hard-won. For four decades, the Connecticut affiliate of Planned Parenthood waged a “polite but persistent campaign,” as John W. Johnson calls it in Griswold v. Connecticut: Birth Control and the Constitutional Right of Privacy (University Press of Kansas, 2005), to repeal the anti-contraception law, both in the legislature and in the courts. A few years later, a younger generation waged a less-polite campaign, this one to overturn the state’s anti-abortion law. In a political landscape dramatically changed by the women’s liberation movement, they had smoother sailing: a federal court declared Connecticut’s anti-abortion law unconstitutional in 1972.

The story of Griswold v. Connecticut is then both a story of women activists’ struggle to do away with laws limiting control of reproduction and of the decision’s importance in the judicial extension of privacy rights. In demonstrating that rights must be fought for, it is also a story for our own time.

Griswold and the Road to Reproductive Rights

In 1923 Katharine Houghton Hepburn and other former suffrage leaders founded the Connecticut Birth Control League (CBCL), an affiliate of Margaret Sanger’s American Birth Control League. They were joined by other women of standing and means who had access to contraceptives from private physicians but wanted to make them available to women who could not afford them. With support from progressive physicians and liberal Protestant and Jewish clergy, the volunteers were dedicated and efficient organizers determined to get rid of the offending law.

In July 1935, immediately after its seventh unsuccessful campaign, the CBLC opted for direct action by setting up a birth-control clinic in Hartford. Operating as the “Maternal Health Center,” the clinic proceeded cautiously, accepting only married women who were referred by unimpeachable sources and who had given birth to at least one child. (Many had four or five.) Initially at least, the two part-time physicians prescribed contraceptives only for reasons of health. “Now as I think of it,” the clinic’s medical director Hilda Crosby Standish observed years later in an interview with Carole Nichols (Connecticut State Library, 1980), “it was just ghastly to have been so strict.” The patients were mainly working-class and immigrant women, the majority of them Catholic; Jews and some African Americans sought out the clinic as well. Fees were based on income and waived for the poorest, many of them on relief. The clinic idea caught on and by 1939 there were nine scattered across the state.

But the clinics came to an untimely end. Following public denunciation by the Catholic clergy, the Waterbury clinic was raided by local law enforcement in June 1939, two doctors and a nurse arrested, and its records seized. A vigorous campaign on behalf of the defendants ensued, but in March 1940 the Connecticut Supreme Court of Errors found no implied medical exception in the original law. The CBLC shut down the clinics, which had collectively served some 9,000 patients. By 1950, many fruitless campaigns later, Connecticut was a true outlier: the Comstock Act had been effectively nullified in the 1930s when a federal court allowed the transport of contraceptives for medical use, and state laws now regulated advertising and dissemination. Only neighboring Massachusetts still prohibited sales.

Things looked up in the mid-1950s after Estelle Griswold became director of the Planned Parenthood League of Connecticut (PPLC, formerly CBCL). As a working-class Catholic who had trained to be a singer, she seemed an unlikely choice. But she was a woman of strong convictions who observed in a 1976 interview with Jeannette B. Cheek (Schlesinger Library) that she considered the law “ridiculous” and the campaign to legalize birth control on a par with the anti-slavery and pro-suffrage movements.

A daring leader and bold strategist, Griswold orchestrated a legal assault on the law, drawing together a stellar medical and legal team. C. Lee Buxton, chairman of Yale University’s Obstetrics and Gynecology Department and head of its infertility clinic, deplored the class inequities of the law and blamed it for the death of two patients. Fowler V. Harper, a professor at Yale Law School, and Catherine Roraback, a progressive trial lawyer with a Yale law degree, were the chief legal consultants; after Harper’s death, Thomas I. Emerson, a professor of constitutional law at Yale, argued Griswold before the Supreme Court.

The team hoped that the law would be declared unconstitutional or at least inapplicable in cases considered dangerous by physicians. Starting in 1958 they initiated suits on behalf of anonymous married couples: in one case, pregnancy endangered the woman’s life, another entailed economic hardship, while a third woman had experienced several unsuccessful pregnancies and could not face another. The cases went nowhere in the Connecticut Supreme Court, and in June 1961 the U.S. Supreme Court refused to hear an appeal because of the availability of contraceptives and the presumed lack of enforcement in the state. Justice Felix Frankfurter’s famous dismissal in Poe v. Ullman—“This Court cannot be umpire to debates concerning harmless, empty shadows” —failed to recognize that in the absence of subsidized birth control clinics after 1940, the law had indeed been enforced—in a way that discriminated against low-income families.

Inviting a test case, Griswold and Buxton opened a birth control clinic at 79 Trumbull Street in New Haven on November 1, 1961. Ten days later, following a complaint from a Catholic father of five who considered a birth control clinic “like a house of prostitution,” New Haven authorities shut down the clinic. During the clinic’s brief life, 42 married women had received contraceptive services. Three of them agreed to testify against Griswold and Buxton, who were charged and convicted for aiding and abetting the users—who, by prearrangement, were not charged.

Four years later, the U.S. Supreme Court dismissed the case against Griswold and Buxton—and with it Connecticut’s anti-contraception law—by a vote of 7 to 2. Speaking for the Court, Justice William O. Douglas held that marriage was a form of association that fell within a “zone of privacy” that was constitutionally protected from government intrusion. “[O]lder than the Bill of Rights,” this right of privacy protected marriage, which Douglas described as “a coming together…intimate to the degree of being sacred” and “an association for as noble a purpose as any involved in our prior decisions.” A law forbidding the use of contraceptives threatened to have “a maximum destructive impact upon that relationship” and could not stand.

Griswold was a fitting apotheosis of the sanctification of marriage in the 1950s. It took another seven years for the court to extend the right of privacy to individuals, married or single. In Eisenstadt v. Baird (1972), the court held by a 6-to-1 vote that a Massachusetts law criminalizing the distribution of contraceptives to unmarried individuals was a denial of their equal protection rights.

Griswold v. Connecticut was alternately hailed as a constitutional breakthrough for individual rights and condemned as judicial overreach. It was unquestionably a triumph for Estelle Griswold and PPLC. Freed from its prior constraints, the organization reopened the clinic; others offering contraceptive and basic health services to lower-income women followed, bringing Connecticut in line with practices in other states.

Controversy over control of reproduction did not end with Griswold. From the start Planned Parenthood had taken pains to distinguish contraception from abortion, which was illegal in every state; some, including Connecticut, allowed exceptions to save a woman’s life. Change came in the 1960s from two directions, as Linda Greenhouse and Reva Siegel document in Before Roe v. Wade: Voices That Shaped the Abortion Debate Before the Supreme Court’s Ruling (2d ed. 2012, documents.law.yale.edu/before-roe). Physicians and clergy, concerned about deaths from illegal abortions, favored legal changes that allowed “therapeutic” abortions to preserve the physical or mental health of the woman; by 1970 thirteen states had reformed their laws accordingly. By contrast, supporters of women’s liberation, who viewed anti-abortion laws as a signal mark of women’s social subordination and highlighted their harm to women (rather than to doctors), favored repeal rather than reform; four states had made this leap by 1970.

Young women activists from New Haven were among those pushing intellectual and political boundaries. Making women’s need to control reproduction central to their program, they hoped to educate and mobilize large numbers of women to end abortion restrictions. In the process they developed a new model of activism, a “lawsuit as organizing tool,” in Amy Kesselman’s words (“Women versus Connecticut,” Abortion Wars: A Half Century of Struggle, 1950-2000, ed. Rickie Solinger, University of California Press, 1998). The group, known as Women versus Connecticut, filed a lawsuit in 1971 to which 858 women signed on as plaintiffs. (The number later climbed to 1,700.) With an all-female legal team, led by Catherine Roraback, they challenged the anti-abortion law on multiple grounds, including denial of the rights to privacy, to life, liberty and property, and—for poor women—to equal protection.

Two of the three federal judges who heard the case declared the state’s anti-abortion law unconstitutional—twice! Following their decision in April 1972, the legislature, at the urging of Governor Thomas Meskill, passed a new anti-abortion statute that exacted harsher penalties. In September, the same judges—both appointed by Republican presidents—declared that statute unconstitutional as well. The decision, Abele v. Markle, cited the rulings on privacy in Griswold and Baird (the latter decided earlier in the year), with Judge Edward Lumbard giving considerable weight to the harms the laws imposed on women and Judge Jon O. Newman suggesting that the state might not have a legitimate interest in the fetus until viability. Their opinions influenced the majority decision in Roe v. Wade a few months later.

On January 22, 1973, the U.S. Supreme Court legalized abortion by striking down two state statutes, each by a 7-to-2 vote: in Roe v. Wade, a Texas law that criminalized abortion except to save the woman’s life, and in Doe v. Bolton, a Georgia law that allowed therapeutic abortions. Writing for the majority in Roe, Justice Harry Blackmun cited Griswold as a precedent, holding that the right of privacy “is broad enough to encompass a woman’s decision whether or not to terminate her pregnancy.” In recognizing the potential physical and psychological harms that life-threatening or unwanted pregnancies could impose, Roe acknowledged women’s special need to control reproduction. But the language and approach were largely medical. The decision to terminate was a private matter between the woman and her physician, with emphasis on the physician. Privacy was absolute only in the first trimester; as pregnancy progressed, the decision held, the state had a growing and eventually compelling interest in protecting the woman’s health and “potential life.” Controversial though Roe later became, in 1973 the majority of Americans agreed that abortion should be a private matter between a woman and her physician (as they had agreed with the central premise of Griswold eight years earlier and would agree about same-sex marriage in 2015).

On January 22, 1973, the U.S. Supreme Court legalized abortion by striking down two state statutes, each by a 7-to-2 vote: in Roe v. Wade, a Texas law that criminalized abortion except to save the woman’s life, and in Doe v. Bolton, a Georgia law that allowed therapeutic abortions. Writing for the majority in Roe, Justice Harry Blackmun cited Griswold as a precedent, holding that the right of privacy “is broad enough to encompass a woman’s decision whether or not to terminate her pregnancy.” In recognizing the potential physical and psychological harms that life-threatening or unwanted pregnancies could impose, Roe acknowledged women’s special need to control reproduction. But the language and approach were largely medical. The decision to terminate was a private matter between the woman and her physician, with emphasis on the physician. Privacy was absolute only in the first trimester; as pregnancy progressed, the decision held, the state had a growing and eventually compelling interest in protecting the woman’s health and “potential life.” Controversial though Roe later became, in 1973 the majority of Americans agreed that abortion should be a private matter between a woman and her physician (as they had agreed with the central premise of Griswold eight years earlier and would agree about same-sex marriage in 2015).

Griswold’s Legacy

Opinion over abortion is more divided today, although support for the basic right has remained remarkably stable over the decades. Since Roe, the U.S. Supreme Court has chipped away at the degree of privacy allowed in the first trimester by upholding state-imposed restrictions such as parental consent and waiting periods. But the justices have continued to employ the standard set in Planned Parenthood v. Casey (1992) that such regulations should not pose an “undue burden” on a woman’s right to an abortion, most recently in Whole Woman’s Health v. Hellerstedt (2016), which invalidated a Texas law requiring clinic facilities to meet hospital standards and clinic doctors to hold admitting privileges at nearby hospitals.

Still, the freedoms advanced in Griswold and Roe are under threat today. Following cuts in state funding to abortion providers, many public clinics have closed, reducing options for low-income women, a situation that will get worse if the U.S. Congress makes good on its repeated threats to defund Planned Parenthood. Even birth control has again become controversial. In Burwell v. Hobby Lobby (2014), the court exempted certain corporations from adhering to a federally mandated contraceptive provision if the owners objected on religious grounds—a different kind of freedom than the privacy granted in Griswold.

In view of the unsettled state of politics and law today, just what kind of breakthrough was Griswold? Limiting the right of sexual privacy to married couples was probably inevitable given Griswold’s origins in 1950s family values. So was its failure to recognize women’s unique relation to reproduction. (There was not even a common public language for understanding this in 1965.) Nevertheless, by establishing a right to sexual privacy and removing government restraints on regulating family size, Griswold has been of momentous consequence for women. As Justice Ruth Bader Ginsberg passionately argued in a 2007 dissent, control of reproduction is of core importance to “a woman’s autonomy to determine her life’s course, and thus to enjoy equal citizenship stature.”

Griswold is best viewed as a point along a spectrum, a beginning and a resting place, rather than an end in itself. As Rosemary A. Stevens, a historian and witness in the case, observed in“Being There” (Connecticut Historical Review, 2015), it was “a point of resolution along the road to reproductive rights.” We have yet to reach the end of that road. And we still need Griswold and its progeny to get there.

Barbara Sicherman is William R. Kenan, Jr. Professor Emerita, Trinity College. She last wrote “Women Who Changed the World,” Summer 2011.

Explore!

“Women Who Changed the World,” Summer 2011

“Birth Control and Zones of Privacy,” Fall 2014