© Connecticut Explored Inc. Winter 2018-2019

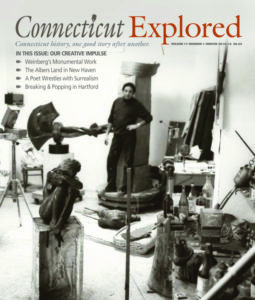

The Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art’s exhibition Monsters and Myths: Surrealism and War in the 1930s and 1940s, on view through January 13, 2019, provides an occasion to examine the impact of surrealism on Connecticut’s greatest poet, Wallace Stevens (1879 – 1955). The years covered by the exhibition, the 1930s and 1940s, mark the crucial transitional period in Stevens’s poetic career, when he transformed himself from the aesthete of his first book, Harmonium (1923), to the more ambitious poet of “the act of the mind.” The surrealist movement played an important part in this self-transformation.

Stevens moved to Hartford from New York in 1916 and lived here for the rest of his life, working as a lawyer for the Hartford Accident and Indemnity Company, where he became a vice president in 1934. He dressed the part of an insurance executive, too, wearing his customary grey, three-piece suit even when watering his garden at 118 Westerly Terrace or relaxing in nearby Elizabeth Park.

It may seem strange to think of such a conventional character in the context of surrealism. But this staid, buttoned-up exterior masked a wild imagination. Harmonium shares many characteristics with surrealism. The nose-thumbing humor of “A High-Toned Old Christian Woman, (“fictive things / Wink as they will. Wink most when widows wince”), the brash color combinations of “Disillusionment of Ten O’Clock” (“purple with green rings, / Green with yellow rings, / Or yellow with blue rings”), and the outrageous sound effects of “Bantams in Pine-Woods” (“Chieftain Iffucan of Azcan in caftan / Of tan with henna hackles, halt!”), all might be labeled surreal. Stevens was predisposed to appreciate surrealism.

The surrealist movement was officially launched in Paris in 1924 when André Breton declared, in the First Manifesto of Surrealism, “I believe in the future resolution of these two states, dream and reality, which are seemingly so contradictory, in a sort of absolute reality, or surreality.” In keeping with that notion, the surrealists sought to free the irrational powers of the unconscious.

The first surrealist exhibition in the United States—“Newer Super-Realism”—took place at the Wadsworth Atheneum in 1931. Stevens attended that exhibition “not just once, but quite a number of times,” according to Hartford art collector James Thrall Soby in Peter Brazeau’s Parts of a World: Wallace Stevens Remembered (North Points Press, 1985). Surrealism soon took the whole country by storm, acquiring a good deal of notoriety along the way. Stevens was deeply ambivalent about the movement. Although he was inspired by its youthful energy, praising the work of Joan Miró as “miraculous,” for instance, he deplored the flamboyant, publicity-grabbing stunts of Salvador Dalí, who once arrived in New York wearing a loaf of bread as a hat. Stevens also feared being classified as a surrealist himself, and with good reason: in 1936, an editor rejected a group of his poems as “tainted with surréalisme.” How could he develop his own, distinctive poetic voice amid the distracting din of the surrealist juggernaut?

Stevens solved this problem in writing his breakthrough poem, “The Man with the Blue Guitar” (1937). The title image clearly evokes Pablo Picasso’s The Old Guitarist (1903), which Stevens saw at the Atheneum in 1934. The man with the blue guitar is both Picasso and Stevens. But it was really the surrealist Picasso of the 1930s that inspired this poem. In Minotauromachia (1935), an etching from Picasso’s surrealist period that Stevens saw in the French art magazine Cahiers d’art, the mythological figure of the minotaur—half man, half bull—represents the artist himself. The bull’s head stands for the irrational forces of the unconscious mind. Stevens plays with a similarly monstrous conception in his poem when he transforms the traditional dichotomy of body and soul into “person” and “animal” (section xvii):

The person has a mould. But not

Its animal. The angelic ones

Speak of the soul, the mind. It is

An animal. The blue guitar—

On that its claws propound. . . .

As he explained in a letter to his Italian translator, Renato Poggioli, “Anima = soul = animal. . . . The soul is the animal of the body.”

As he explained in a letter to his Italian translator, Renato Poggioli, “Anima = soul = animal. . . . The soul is the animal of the body.”

Breton demanded strict adherence to surrealism’s core principles. But he made an exception in the case of Picasso, the undisputed leader of modern art. So Stevens, by identifying with Picasso in “The Man with the Blue Guitar,” was asserting his own superiority to the narrow restrictions of the movement. This bold, imaginative gesture resulted in his most successful long poem to date. It was a crucial step toward the great poetry of his later career.

Glen MacLeod is professor of English at the University of Connecticut. He has published Wallace Stevens and Company (1983), Wallace Stevens and Modern Art (1993), and Wallace Stevens in Context (2017).