By Linda Hocking

(c) Connecticut Explored inc. Fall 2018

SUBSCRIBE/BUY THE ISSUE

This age of bitter partisanship seems the perfect time to reflect upon the career of Connecticut’s statesman Oliver Wolcott Jr. (1760 – 1833), who rose above the bitter rancor of party politics to preside over the creation of a state constitution in 1818.

The oldest surviving child of Oliver Wolcott Sr. (1726-1797) and Lorraine (Laura) Collins of Litchfield, Wolcott was born to a family of prominence and means. His paternal grandfather, Roger Wolcott, was deputy governor of the Connecticut Colony from 1741 to 1750. His father was a member of the Continental Congress throughout the Revolutionary War and signed the Declaration of Independence. He was also commissioner of Indian affairs and a major general in the Connecticut militia. Laura took charge of family affairs. Samuel Wolcott’s The Memorial of Henry Wolcott, One of the First Settlers of Windsor, Connecticut and of Some of His Descendents (Randolph and Company, 1881) notes that, “During [Oliver Sr.’s] almost constant absence from home while engaged in the arduous service of the Revolutionary War, [Laura] educated their children and conducted the domestic concerns of the family, including the management of a small farm, with a degree of fortitude, perseverance, frugality, and intelligence, equal to that which in the best days of ancient Rome distinguished her most illustrious matrons.”

Young Oliver entered Yale College in 1774. His ideas were barely formed and his education not yet complete when the outbreak of war took his father from home. Because various skirmishes took place not far from Yale, he joined the conflict, too, without abandoning his studies, participating in the Battle of Ridgefield in April 1777.

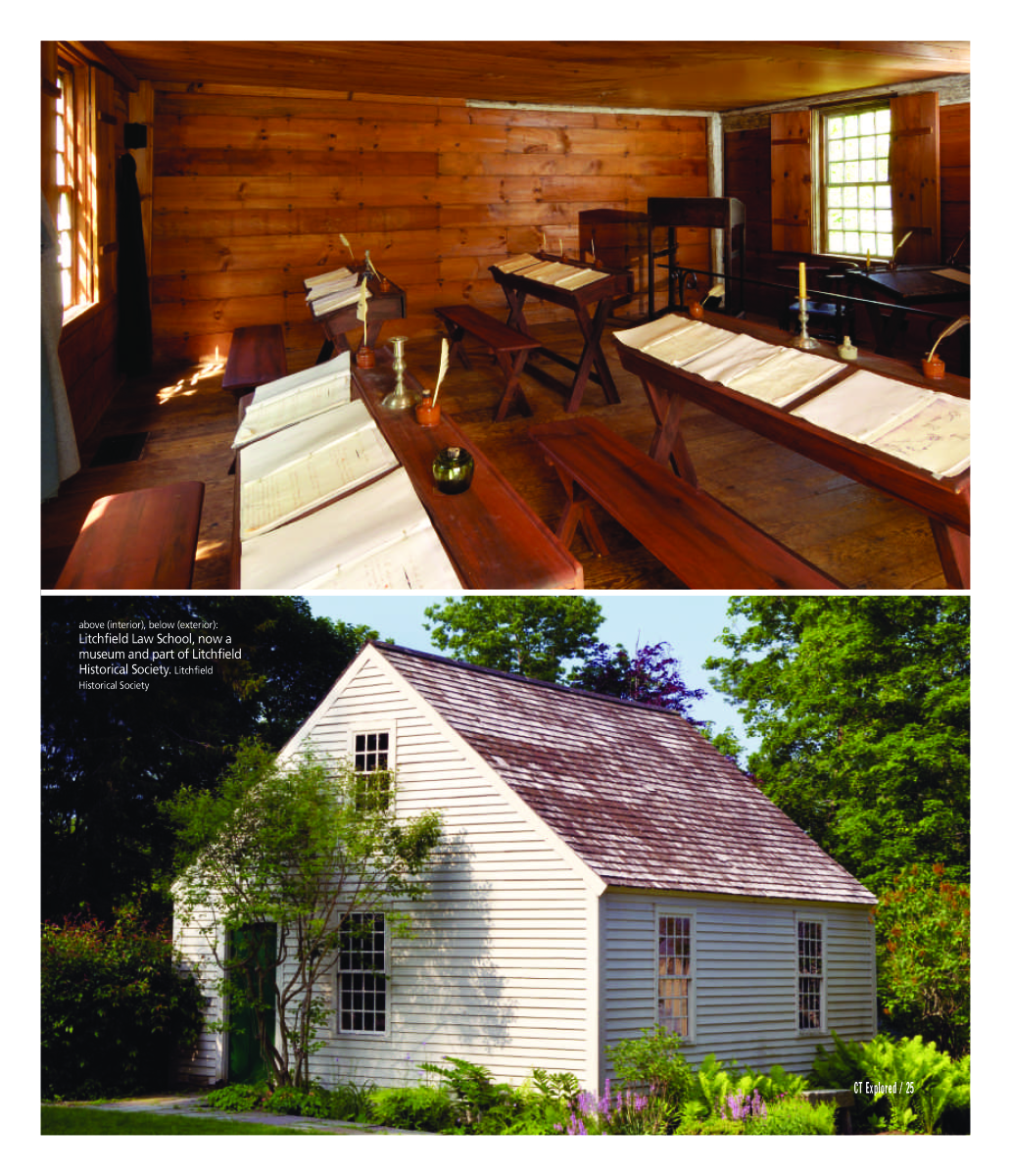

Tapping Reeve Law School, now a museum and part of the Litchfield Historical Society. Courtesy of Litchfield Historical Society

Wolcott graduated from Yale in 1778 and took up the study of law with Tapping Reeve, whose Litchfield Law School was across the street from his family home. He simultaneously served in various capacities in the Continental Army. Because Litchfield was at a major crossroads and served as a supply depot during the war, he had the opportunity to meet many notable people, including George Washington and Alexander Hamilton, who were guests at his home.

In 1781 Wolcott was admitted to the bar and left for Hartford, where he became a clerk for the Committee of the Pay Table, a group that oversaw the state’s military expenses for the Revolutionary War. In the same year, he earned a master’s degree from Yale. His diligent and hardworking habits did not go unnoticed. In 1782 he was promoted to membership on the Committee of the Pay Table and, just two years later, named a commissioner for the State of Connecticut to oversee the settlement of accounts with the federal government.

Wolcott continued serving the state until 1789, when he was offered a position as auditor of the Federal Treasury, working closely with Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton. According to The U.S. Department of Treasury website (treasury.gov), “Beginning in 1789, Oliver Wolcott Jr. played an important role in the organization of the nascent Treasury Department.” Meanwhile, his father was elected lieutenant governor of Connecticut in 1786. (He would serve one year as governor in 1796 before dying in office the following year.)

Alexander Hamilton had great confidence in young Wolcott’s abilities and lobbied for his appointment as comptroller of the United States Treasury in 1791. He wrote to President George Washington on April 17,

Indeed I ought to say, that I owe very much of whatever success may have attended the merely executive operations of the Department to Mr. Wolcott; and I do not fear to commit myself when I add, that he possesses in an eminent degree all the qualifications desirable in a Comptroller of the Treasury; that it is scarcely possible to find a man in the United States, more competent to the duties of that station than himself—few who could be equally so… In addition to the rest, Mr. Wolcott’s experience in this particular line pleads powerfully in his favour. This experience may be dated back to his office of Comptroller of the State of Connecticut, and has been perfected by practice in his present place.

After Hamilton resigned in 1795, Washington appointed Wolcott as secretary of the treasury. Wolcott continued in that role under President John Adams, though he was frequently at odds with the Adams administration. Historian Neil A. Hamilton, in Mercantilist Economics: The Life of Oliver Wolcott, Jr.(University of Tennessee, Knoxville, 1988), argues that Wolcott “generally supported Hamilton’s program of funding, assumption, and the national bank which intended especially [to]boost financial and commercial activities.” Wolcott remained steadfast in his convictions that the government should assist industry, commerce, and agriculture. Rather than blindly follow party allegiances, he expressed areas of discord with the Adams administration and gave preference to his economic views over views of any one political party.

Wolcott resigned in 1800 “under a storm of criticism from Jeffersonians in Congress,” according to treasury.gov. He urged a congressional investigation of the U.S. Treasury Department in 1801 to clear his name.

Having lost faith in Adams’s ability to lead the government, Wolcott joined Hamilton in supporting South Carolina’s Charles Pinckney as the Federalists’s candidate for president in 1800. Despite this, in the final days of his presidencyAdams appointed Wolcott judge to the Second Circuit of the United States under the Judiciary Act of 1801. In a letter dated April 6, Adams wrote a reply to Wolcott’s letter of thanks for the nomination: “Twenty years of able and faithfull services on the Part of Mr. Wolcott remunerated only by a simple subsistence, it appeared to me constituted a claim upon the Public which ought to be attended to…I wish you much Pleasure and more honor in your Law Studies and Pursuits and doubt not you will contribute your full share to make Justice run down our Streets as a Stream.”

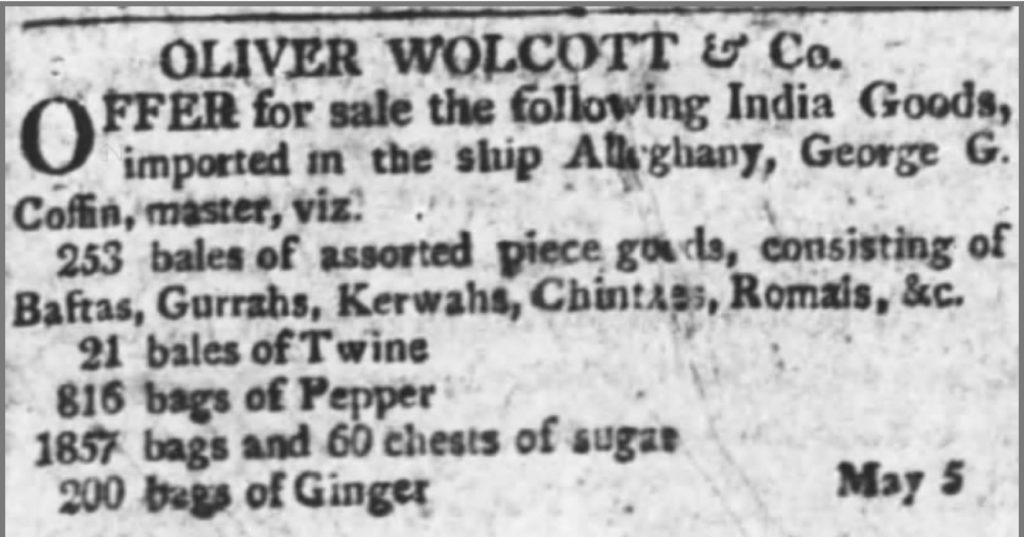

Wolcott’s judicial career was brief. In 1802 the U.S. Congress repealed the Judiciary Act, leaving him without an income. He established a short-lived mercantile venture in New York, Oliver Wolcott & Company, which closed in April 1805.

Around that time Wolcott began a new enterprise, the Litchfield China Trading Company. Though Wolcott was still based in New York, his investors were all from Litchfield. They included his brother, Frederick Wolcott, and merchant Benjamin Tallmadge. Another Litchfield merchant, Julius Deming, later joined the firm.

Wolcott procured the Trident, a nearly-new vessel, to carry out the trade. It completed its first voyage in 1804, and by 1805 a second ship, the Virginia, set sail for India. The partners signed an agreement to finance four successive voyages to China, beginning in the spring of 1806. Wolcott advertised the availability of newly imported items at the firm’s storefront in New York, including several varieties of tea, yellow and white nankeen, silks, and pearl-handled combs. China and lacquered ware were later added. Their imported goods were also sold in Litchfield and by Belden, Dwight & Company in New Haven.

When President Thomas Jefferson signed the Embargo Act of 1807 in an attempt to retaliate against British and French impressments of American seamen and ships, foreign trade was effectively halted. To allay his brother’s fear of their firm’s failing, Wolcott wrote Frederick in January 1808,

It is natural for you to feel concern respecting our China Trade. I can assure you, that the danger is less than appears at your distance. No Merchants have failed, who were not insolvent before the Embargo. Large sums are due our concern, but in general they are due from the best men in the City…There is no immediate danger of War& the Ship & Cargo out, are not embraced by any of the decrees of either of the Parties to the War. The Ship & Cargo are insured against all risques even War, in the best offices here & in Philadelphia…Tell Mr. Demming what I write & Keep yourself cool, for I assure you that we are not in any new danger, unless the British perfidiously swept our Commerce from the Ocean, which is not in the least probable.

Yet in April Wolcott announced to Frederick, “…we have concluded to send out the Trident with a moderate Investment & to close the existing concern with the depending voyage.” After this voyage to China in 1810, the Trident was sold and The Litchfield China Trading Company was dissolved.

Concerns over the Embargo Act led Federalists in New England to consider seceding from the union, but Wolcott remained committed to protecting the republic established by the Revolutionary War. Wolcott again split from the Federalists when he supported James Madison for president and the War of 1812, believing, according to Neil Hamilton, that the war would help preserve New England manufacturing, in which he had invested. He quotes Wolcott, writing to Rufus King in July 1812, “I am by habit and education, both a Whig and a Federalist and I know that these characters are not incompatible.” He would not be constrained by dictates of party.

His political views caused perpetual problems with his business interests, however. Merchant’s Bank asked him to become its president in 1803 but then failed to receive a charter from the State of New York until 1805. As Neil Hamilton notes, when, a decade later, Wolcott began openly supporting candidates who favored the war, he lost the approval of the Federalists, who removed him from his role as president of the Bank of America. The Newark, New Jersey Centinel of Freedom wrote on May 10, 1814,

Oliver Wolcott, Esqr (formerly Secretary of the Treasury under the administration of President Adams,) was one who took part in favor of the Washington federal ticket, in the late election in the city of New York. He was at that time President of the Bank of America. Since that time an election of Directors has taken place, and Mr. W. is left entirely out of the Board of Directors. We leave the reader to guess the cause!

After the War of 1812 ended, Wolcott returned to Litchfield, where he entered into a woolen manufacturing pursuit with his brother Frederick. His continued financial struggles must have helped shape his views of the troubles plaguing Connecticut. Emigration to the North and West threatened to remove young workers from Connecticut’s economy. Wolcott saw high taxation as a detriment to business growth and believed the answer to the state’s problems could be found in supporting agriculture and expanding industry.

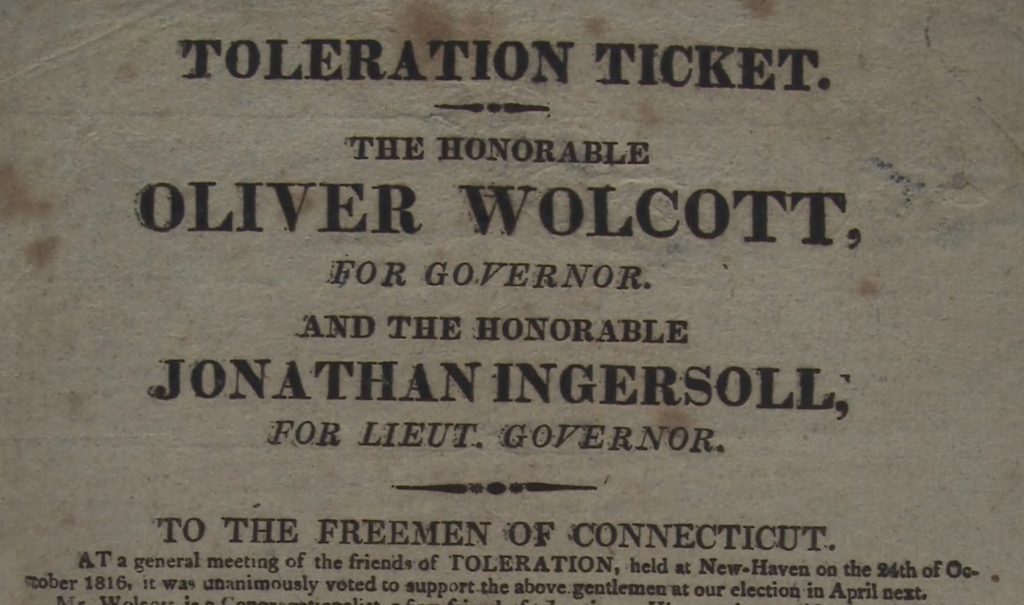

Having spent little time in Connecticut in recent years, Wolcott was a surprising choice in 1816 to lead the newly formed Toleration Party ticket in Connecticut’s elections, according to historian Richard J. Purcell in Connecticut in Transition: 1775 – 1818 (Wesleyan University Press, 1963). Seeking to capitalize on the disgrace of the Federalists in the wake of the Hartford Convention, a new coalition political party was forming to unite the state’s many disgruntled minority factions. Purcell called Wolcott “a compromise between the old order and the new; an ideal man to work out the state’s transition.” The Toleration Party, which included Republicans, Baptists, and Methodists, eagerly courted Episcopalians and realized the potential benefits a gubernatorial candidate with the name Wolcott could bring to the new party.

Although conservative, Wolcott was open to the idea of disestablishing the Congregational Church. On March 1, 1816, the New-England Palladium & Commercial Advertiser of Boston, Massachusetts reported, “The restless Democrats of Connecticut have again had a caucus, and determined Candidates for the first offices in that State. They are playing an artful game, and have had the presumption to propose to their party to vote for the Hon. Oliver Wolcott for Governor.”

Wolcott lost his first bid in 1816 to John Cotton Smith, but the Toleration Party made gains in the state legislature. The same slate of candidates was put forth the following year with better results. Though he didn’t campaign or solicit the nomination, Wolcott was elected governor. He wrote to his son-in-law George Gibbs from Litchfield on April 7, 1817,

In this Village, Gov. Smith had 222, and your humble servant 322 votes. I own that I am pleased with obtaining the majority in this Town, as every possible exertion has been made to oppose me. … I knew my ConntComrades well; when a strange animal, as they consider me, comes among them, they first attempt to knock him on the head. If they find him too strong, they will make peace on pretty fair terms, and like him the better for having resisted them. I do not want an office, but I could not decline this Contest with Honour nor with Safety.

According to the July 22, 1817 Centinel of Freedom, Tolerationists in Hartford raised an Independence Day toast in honor of “Oliver Wolcott—Governor of the State, not of a Party.” His service as governor over the next 10 years would prove that sentiment true. Purcell noted, “Wolcott expressed moderate views, encouraging cooperation and compromise…He was the people’s rather than a party governor.”

Wolcott’s first address to the Connecticut General Assembly in May 1817 called for reviews of manufacturing laws, taxation, suffrage, and religious freedom. He also led a call for prison reform. When he ran for re-election the following year, Wolcott’s moderate tone set the stage for the coming Constitutional Convention. As reported in New York’s National Advocateon May 20, 1818, he addressed the legislature, saying,

A portion of our fellow citizens … are now desirous… that the legislative, executive, and judicial authorities of their own government, may be more precisely defined and limited, and the rights of the people declared and acknowledged. It is your providence to dispose of this important subject…

A select committee of five members of the general assembly first took up the important subject. The legislature then ordered the freemen of each town to meet on July 4, 1818 to elect representatives to a convention in August. Neil Hamilton notes that although the representatives chose Wolcott as president of the convention and he submitted a draft of a new constitution, the delegates voted to select a committee of 24 members, three from each county, to draft the document.

A select committee of five members of the general assembly first took up the important subject. The legislature then ordered the freemen of each town to meet on July 4, 1818 to elect representatives to a convention in August. Neil Hamilton notes that although the representatives chose Wolcott as president of the convention and he submitted a draft of a new constitution, the delegates voted to select a committee of 24 members, three from each county, to draft the document.

The proposed constitution was voted on in October. It passed by 1,554 votes: 13,918 in favor and 12,364 opposed. The constitution disestablished the Congregational Church, expanded white male suffrage, and decreased taxes. Wolcott quickly called for a review of laws to align with the new constitution.

Wolcott continued to work with the legislature on his priorities of improving manufacturing and decreasing taxes. In 1826 he was successful in convincing the legislature to replace New-Gate Prison with a more modern facility in Wethersfield.

The following year, after 10 years in office, Wolcott was dropped from the Republican ticket amid rumors that he wished to retire, Neil Hamilton reports. A group of supporters backed him as an independent candidate, but he lost by fewer than 2,000 votes. He moved to New York City, where he died on June 1, 1833.

Linda Hocking is curator of library and archives for the Litchfield Historical Society. She last wrote “Say It With a Card,” Winter 2017-2018.

Explore!

Litchfield Historical Society, Tapping Reeve House, and Litchfield Law School

Open mid-April to November, free admission

7 South Street and 82 South Street, Litchfield

litchfieldhistoricalsociety.org, 860-567-4501

LISTEN!

Grating the Nutmeg

Episode 47: America’s First Law School, Sarah Pierce’s Academy, & “The Way We Mourned”

Episode 15: What’s It All About: Law and Order Edition. The second segment, starting at minute 17, features the Litchfield Law School

READ MORE!

The Influence of the Litchfield Law School, Fall 2016