By Lauren Borsa-Curran

(c) Connecticut Explored, Summer, 2023

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

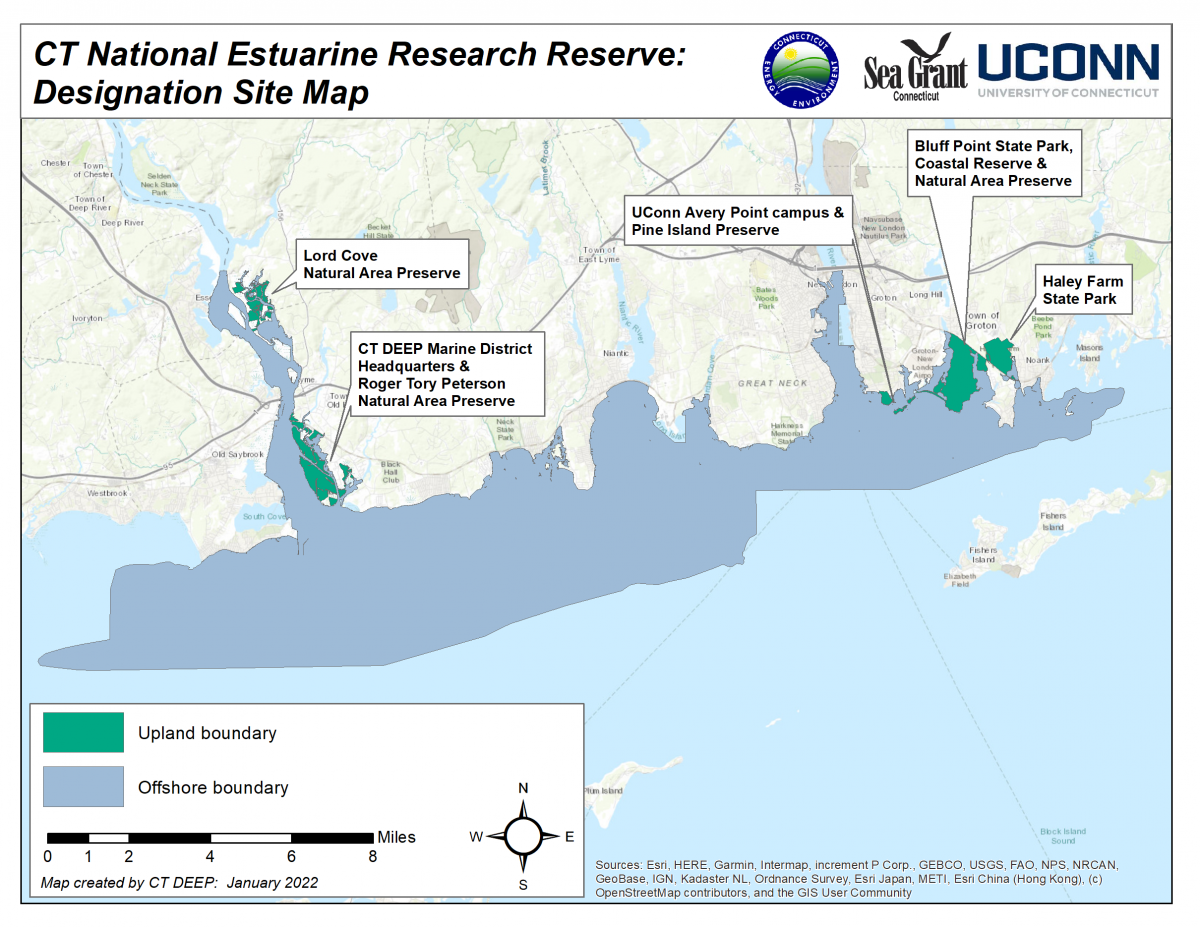

Just a quarter of a mile off the coast of Groton, near the University of Connecticut’s Avery Point campus, sits a small, uninhabited island covered with old stone walls and brambles. The ebb and flow of the tide is the only sign of life on this nearly 15-acre landform, a testament to an industry that once thrived here that was reliant on the tiny, silver fish that did and still do swim its waters. Pine Island, now owned by the University of Connecticut and named for the tree species that grew there in colonial times, was once home to a summer retreat, a fish oil company, a fertilizer factory, and a gun battery during World War II. It is also a Connecticut State Archaeological Preserve. In her 1852 History of New London, Connecticut from the First Survey of the Coast in 1612 to 1852, Frances Manwaring Caulkins noted that during the 17th century “plow maker John Cole” received “‘the marsh upon pyne island.’” She added, “This island, or islet, which lies on the Groton shore, still retains its designation, though long since denuded of the original growth of pines from which it was derived.”

Vacation Spot

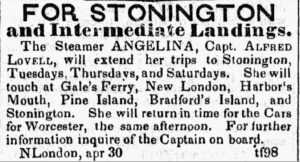

An ad for the steamer Angelina, Morning News, April 30, 1846, image: America’s Historical Newspapers

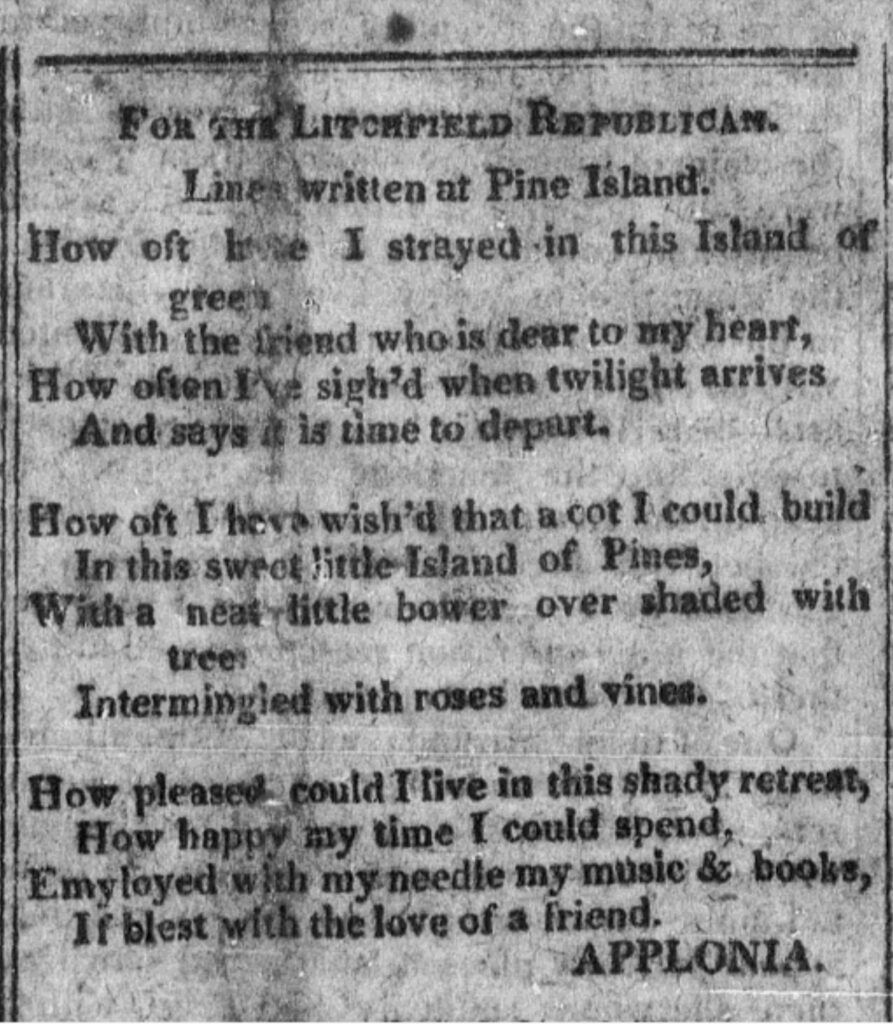

The Stoddard family launched the island’s time as a vacation spot, buying it in 1823 and building a resort “so popular that the steamer Angelina made regular stops there on its route between New London and Stonington,” according to Ross K. Harper in his article “Pine Island, Groton, Connecticut, Archaeological Preserve” published by the Council for Northeast Historical Archaeology in June 2013. The Morning News on April 30, 1846 and in subsequent issues published Angelina’s schedule of frequent stops on Pine Island, showing how the island was connected to the shoreline community: “The Steamer Angelina, Capt. Alfred Lovell, will extend her trips to Stonington, Tuesdays, Thursdays, and Saturdays. She will touch at Gale’s Ferry, New London, Harbor’s Mouth, Pine Island, Bradford’s Island, and Stonington.” The island’s beauty attracted people, as evidenced in this line from a poem written about it by someone named Apolonia and published in the Litchfield Republican on April 24, 1820: “How oft I have wish’d a cot I could build in this sweet little Island of Pines.”

“Lines Written at Pine Island,” The Litchfield Republican, April 24, 1820. image: America’s Historical Newspapers

By 1847 John G. Spicer and his wife Clarissa, the widow of Orin Stoddard, owned Pine Island. The 1846 U.S Coast Survey Map of the island shows “a house, several outbuildings and a wharf.” According to Dave D. Davis and Jeffrey Maymon in “Pine Island: A Coastal Islet’s Storied Past” (published in January 2019 through the State Historic Preservation Office within the Connecticut Department of Economic and Community Development with funds from the National Park Service), Hubbard D. Morgan purchased the island from the Spicer family in 1862, ushering in what would become the island’s major industry, the commercial extraction of oil from menhaden. Morgan became “one of the first entrepreneurs in the region to extract oil commercially from menhaden.”

Menhaden

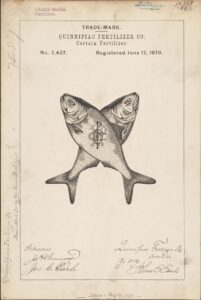

Fatback, Bunker, Pogie, Mossback. You might recognize these names given to the boney, oily fish known as menhaden. It was this herring-like fish, a native of Connecticut waters, with the tiny, dark spot behind its gill opening, that was the mainstay for the livelihood of those who owned and worked for the Pine Island Oil Company. Morgan formed the Pine Island Oil Company with business partner Franklin Gallup. The Quinnipiac Company of Hamden, which had developed new processes for using menhaden for commercial products, purchased a controlling interest in 1864 and in 1871 renamed its operations the Quinnipiac Fertilizer Company.

View of a scoop net loading fish onto an unidentified menhaden steamer. Fish are pouring from the net into the hold. Fish can also be seen on the deck. image: Mystic Seaport Collections, Connecticut Digital Archive

To process the fish, the factory was equipped with two boilers, two hydraulic presses used to extract the oil, and two guano mills that ground up dried remains from the fish. John Frye described the company in his book The Men all Singing: The Story of Menhaden Fishing (Norfolk, VA: Donning, 1978) as a “pioneer” in another aspect of the steam process: use of a floating factory, which helped with one negative aspect of the industry, foul odor. Frye notes the fate of many menhaden: “It is not hard to surmise the menhaden’s place in nature; swarming our waters in countless myriads, swimming in closely-packed, unwieldy masses, helpless as flocks of sheep, close to the surface and at the mercy of any enemy, destitute of means of defense or offense, their mission is unmistakably to be eaten.”

Trademark registration by Quinnipiac Fertilizer Co. for Two fish logo brand Certain Fertilizer. 1879. photo: Retrieved from the Library of Congress

The use of the fish as fertilizer predated its use for oil. Native people in the area, including the Pequot, Niantic (Nehantic), Mohegan, Quinnipiac, and Wangunk, all harvested this very oily fish as fertilizer for planting. According to the National Wildlife Foundation’s blog, “Menhaden: Why We Should Be Thankful for this Tiny Fish,” the word “menhaden” is derived from an Algonquian word for “fertilizer.” It contains high concentrations of nutrients, but it is smelly and almost inedible. Thus, it could only be consumed as food when it was very fresh. It decays quickly, however, making it more suitable for the production of other foods like maize.

Menhaden fisheries were not important just to New England but spanned the Atlantic seaboard and the Gulf of Mexico. Commercial fishing for Atlantic menhaden occurred as early as the mid-1800s. Connecticut’s shoreline and the islands in Long Island Sound were dotted with menhaden processing plants, including the one on Pine Island. In 1880 more than 600 people were employed in the labor-intensive menhaden fish industry in the state, according to “Pine Island: A Coastal Islet’s Storied Past.” As the new nation industrialized, but before electricity was on the horizon, New Englanders turned to less expensive menhaden oil to heat their homes when whale oil became limited due to overfishing. Pine Island’s Quinnipiac Fertilizer Company took advantage of both uses of the fish.

At the end of the 19th century, Quinnipiac Fertilizer ceased operations and the wealthy Morton F. Plant purchased it. He built a mansion known as Branford House on Avery Point, where UConn’s Avery Point campus is now located. According to Groton town historian Jim Streeter’s June 12, 2018 article in The Day of New London, “History Revisited: Pine Island Small in Size, Substantial in History,” there are two headstones amid the bramble on Pine Island, both belonging to the same man, James Baley, who drowned at age 37 in 1788. While one headstone made note of his death, the other, added by Plant, acknowledged Baley’s service in the Revolutionary War. Before he died Baley had been given the eastern section of Pine Island under “a resolution for grants of properties to the people of Groton and the City of New London for their pain and suffering following the Battle of Groton Heights in 1781,” according to the article “Pine Island Soldier,” written by Ken Beatrice and Bonnie Beatrice and published in the Friends of The Office of State Archaeology, Inc. member newsletter in Fall 2005. Plant used the island’s rich topsoil for his own gardens at Bradford House.

In January 2022 the National Oceanic & Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) established Pine Island and another 52,160 acres of Connecticut coastal sites as the nation’s 30th National Estuarine Research Reserve (NERR), a network of coastal sites designated to protect and study estuarine systems. As time passes, the little island continues to rest quietly as nature takes hold. It’s hard to imagine that its sandy shores were once bustling with fishermen and an industry based on a tiny fish that still swims today. Ralph H. Gabriel, in his 1920 article “Geographic Influences in the Development of the Menhaden Fishery on the Eastern Coast of the United States,” Geographical Review 10, no. 2, recalled how elderly Long Islanders could remember a time when a massive school of menhaden swimming near the ocean’s surface was a “spectacle” to see.

Sea birds, flora, and fauna are all that remain on Pine Island’s shore now. While the menhaden fishing industry disappeared long ago, the menhaden remain in the islet’s waters, continuing to nourish marine life and clean the ocean with their filtering capabilities as they have always done.

Lauren Borsa-Curran is a journalist who writes about career development and higher education. She is a former reporter for The Associated Press.