(c) Connecticut Explored, Summer, 2023

By Karen Ali

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

In 1955 residents of Puerto Rico began coming to Windham looking for a better way of life. Word started spreading of plentiful job opportunities in Willimantic, a city that merged with Windham in the 1980s. Some came directly from Puerto Rico, while others moved from other parts of Connecticut and New York. A declining mill town in the 1950s, Willimantic was slated for urban renewal, a movement that accelerated in the 1960s with the creation of the Willimantic Redevelopment Agency in 1966 and grants from the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) to redevelop the central business district in 1969. In 1968 Willimantic applied for a Model City Initiative and included Puerto Rican voices in the process. According to historian Anna D. Jaroszyńska-Kirchmann in her 2021 article “Urban Renewal in a New England Mill Town: Willimantic’s Puerto Rican Community and Redevelopment,” published in Connecticut History Review, those responsible for redevelopment were determined that there would be “no Puerto Rican ghetto.” The people of the island did not want their community to become an island in the midst of their chosen city. They wanted instead to play a vital role in shaping the culture and economy of Windham, and in particular Willimantic, as it transformed itself.

Catina Caban-Owen at the Three Kings Festival in January in Willimantic. The event drew hundreds of residents to the event. photo: Ninoshka Alba photography

Several residents shared their memories and knowledge of how the town changed over the years. Many of their memories focus more on the growth of the community and the challenges it faced than on the urban renewal process itself. Windham resident Dr. Catina Caban-Owen, who in the 1980s became the first Latina person ever to serve on the board of education in Windham, said that in 1955 one person came to work in Willimantic from Juana Diaz, Puerto Rico, and the rest, as she puts it, was history. “And he started bringing other families,” said Caban-Owen. “And here we are.” As of 2020 about 70 percent of the school population in Windham was of Hispanic or Latino heritage, according to the Connecticut State Department of Education’s district profile. The Puerto Rican community’s efforts to become part of the larger Willimantic community focused on hard work and education. At the same time, ties to Puerto Rico itself, the place and its culture, remained close.

Early Challenges

Dr. Ricardo Pérez professor at Eastern Connecticut State University, speaking at Eastern. photo: Yolanda Negrón

In the 1950s those who began migrating to Windham and Willimantic found work with two employers: Hartford Poultry, a chicken-processing plant, and American Thread Company, then one of the largest thread manufacturers in the United States. Dr. Ricardo Pérez, who was born and raised in Puerto Rico, is now a professor of anthropology at Eastern Connecticut State University (ECSU), located in Willimantic. He remembered, “Together, those two companies employed most Puerto Rican migrants in Willimantic.” Hartford Poultry ceased operations in 1972, and American Thread Company in 1985.

Dr. Elsa Núñez, ECSU’s President, said factory managers took advantage of “Puerto Rican workers and their strong work ethic, and workers usually found themselves doing very hard work, and often very dangerous work, for little pay. And what money they did earn often wound up going back to the company officials who hired them in the first place, usually through repayment of loans, room rentals, laundry services, or even meals. Núñez emphasized that having so many Spanish speakers at the factories had the effect of discouraging workers from learning English, keeping Puerto Ricans isolated from the rest of the community.

When Hartford Poultry and American Thread Company shut down in the 1970s and 1980s, respectively, high levels of unemployment among Puerto Rican residents ensued. Pérez said, “With the onset of the post-industrial economy in Willimantic, some workers were re-trained and found employment in several factories that still operated in eastern Connecticut. Others found employment in low-skilled positions at the University of Connecticut, Eastern Connecticut State University, and the Windham Community Hospital.”

Promotion Day at North Windham Elementary School 2018. Approximately 70% of Windham Public Schools students’ population is Latino. photo: Yolanda Negrón

Pérez added that “some of the major challenges faced by the initial Puerto Rican migrants in Willimantic related to the cultural and linguistic differences” between the two. “Learning the English language was surely difficult.” Yet some hurdles were more basic, Pérez explained, including “adapting to the harsh winters in the United States and the inability to keep constant communication with their families back in Puerto Rico.” Pérez recalled, “Many Puerto Rican homes at the time lacked telephones, and mail service between the United States and Puerto Rico was slow-paced.” Perhaps the most difficult obstacle was the crowded and inadequate housing stock available to them in downtown Willimantic.

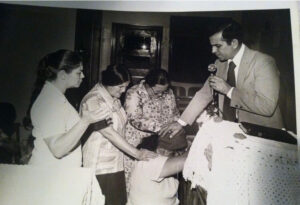

From left: Sister Doris Ríos, Sister Cecilia Feliciano, Sister Iris (Yolanda Negrón’s mother), and Rev. Ramon Luis Negrón, praying for Mariana Pedraza,

at Iglesia Cristiana Pentecostal in Willimantic, founded by Yolanda Negrón’s father Rev. Ramon Luis Negrón. photo: Yolanda Negrón

There were also instances of discrimination, said Yolanda Negrón, who moved with her family in 1974 from Hartford to Willimantic, where her father founded a Pentecostal church that still exists. In 1992 Negrón became the first Puerto Rican elected to serve on the town’s board of selectmen. She recalled a disturbing incident after she was elected: When she was grocery shopping with her father, an angry man came up to her, mentioned her name, hurled racial slurs at her, and then spit at her, telling her to go back to Puerto Rico. The event was upsetting, but Negrón recalls being gratified by the outpouring of support she received from everyone else at the store. “People started yelling at him,” she said, adding that several women took her to the bathroom to wash the spit off her face and comfort her. “What I took away was that not everyone was that way,” said Negrón, who was born in Hartford in 1963 and now lives in Willimantic. The manager called the police and told them he never wanted that man in the grocery store again, she noted. He also refused to let her and her father pay for their two carriages full of groceries.

Luis Díaz (R), pictured in the photo with his goddaughter Yolanda Negrón (L), was one of the first Puerto Rican teachers hired in the 1970s. He taught Spanish at Windham High School. The first Puerto Rican/Latino on the Board of Finance in the 1980s, he served for 10 years. photo: Yolanda Negrón

Catrina Caban-Owen moved to Willimantic in 1979 at age 25 with a Master of Social Work degree from the Graduate School of Social Work at the University of Puerto Rico. When Caban-Owen first arrived, she began working as a social worker for an agency that helped anyone who needed counseling. She left that position in 1992 to work in the public school system as a social worker. Pérez, who has been living in Connecticut since 1994 and in Willimantic since 2001, noted that “social networks already in place allowed them to bring more family members, relatives, and even neighbors from their home communities in Puerto Rico to Willimantic. Today “a good number of Puerto Ricans are homeowners, especially those who also own their own businesses, are self-employed or work in the public school system and the local government,” Ricardo Pérez said. Many Puerto Ricans also work in retail and the service sector in supermarkets, fast food franchises, gas stations, and stores, he added.

Caban-Owen, who works for ECSU and the UConn School of Social Work as part-time faculty, recalls that in 1979 there were only a handful of Puerto Rican residents of Willimantic who were educated middle-class professionals. Many were working-class poor, working manual jobs and in factories, she said. Today there are more professionals in town, many having earned four-year degrees, master’s degrees, and doctorates, said Negrón.

Puerto Rican migration to Windham continues to this day. “As it happened during the second half of the 20th century, Puerto Rico is struggling with the economic slowdowns and the fiscal crisis of the Puerto Rican government,” Pérez said, adding that the 2017 hurricane season and a series of earthquakes since 2019 have exacerbated the economic woes of many Puerto Ricans. “Taken together, the current unfavorable economic situation and the recent environmental catastrophes have pushed Puerto Ricans to migrate to Willimantic and other Connecticut cities,” Pérez said. “Over the years, the Puerto Rican community in Willimantic has maintained an important presence and influence in town.”

Despite Challenges, the Puerto Rican Spirit Lives On

Negrón remembered the Puerto Rican community as being much more tight-knit in the 1980s and 1990s, when it would organize festivals and dances. “Sadly, some of this has been lost,” she said, adding that as the generations assimilate, the cultural element is not as strong as it once was. Pérez concurred: “To me, this case is typical of immigrant communities assimilating to mainstream U.S. culture. For second- and third-generation Puerto Ricans in Willimantic, it is easy to assimilate in the absence of community organizations that can promote Puerto Rican culture. Despite the watering down of Puerto Rican culture over the years as new generations of Puerto Ricans assimilate, the culture and contribution from the Puerto Rican community remains important.

Group photo at the Three Kings Day Celebration in Willimantic in January, which hundreds of Puerto Rican residents attended. photo: Ninoshka Alba photography

Xiomara Bruder, an employee of the town of Windham who organized the town’s first Latin multicultural festival, said that the events in town such as the Windham Latin Multicultural Festival, Music Pa’l Pueblo, the Three Kings Day celebration hosted by the board of education, and the Cinco de Mayo Parade preserve the Latin heritage for future generations. The town, through its Department of Economic and Community Development, has tried to highlight Latino businesses and promote that community’s events.

“By participating in these celebrations, people of all ages are exposed to the culture, history, and tradition of the Latin American community, which helps to keep the culture alive and vibrant,” said Bruder, who came from Puerto Rico as a toddler with her family in 1981.

Núñez said that Latino culture in general, and Puerto Rican culture in particular, is reflected in local restaurants, markets, and stores, in numerous places of worship, in the music one hears throughout town, and in community events. “Puerto Rican-owned businesses have created countless local jobs throughout the area, and Willimantic may be one of the most diverse and inclusive communities of its size in all of Connecticut. The Latino community has an enormous presence here and has made a huge impact on the intangible qualities that give Willimantic its overall vibe that is part eclectic, part quirky, and a lot of fun.”

Karen Ali is a writer, editor, and media strategist. She was born and spent her childhood in Windham County.