(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Fall 2021

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

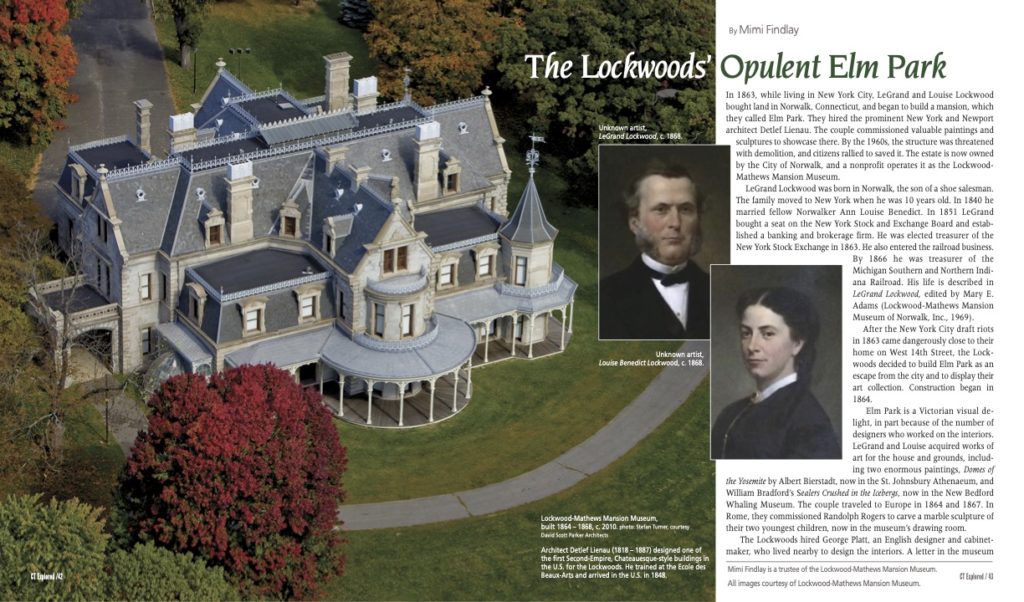

In 1863, while living in New York City, LeGrand and Louise Lockwood bought land in Norwalk, Connecticut, and began to build a mansion, which they called Elm Park. They hired the prominent New York and Newport architect Detlef Lienau. The couple commissioned valuable paintings and sculptures to showcase there. By the 1960s, the structure was threatened with demolition, and citizens rallied to saved it. The estate is now owned by the City of Norwalk, and a nonprofit operates it as the Lockwood-Mathews Mansion Museum.

LeGrand Lockwood was born in Norwalk, the son of a shoe salesman. The family moved to New York when he was 10 years old. In 1840 he married fellow Norwalker Ann Louise Benedict. In 1851 LeGrand bought a seat on the New York Stock and Exchange Board and established a banking and brokerage firm. He was elected treasurer of the New York Stock Exchange in 1863. He also entered the railroad business. By 1866 he was treasurer of the Michigan Southern and Northern Indiana Railroad. His life is described in LeGrand Lockwood, edited by Mary E. Adams (Lockwood-Mathews Mansion Museum of Norwalk, Inc., 1969).

After the New York City draft riots in 1863 came dangerously close to their home on West 14th Street, the Lockwoods decided to build Elm Park as an escape from the city and to display their art collection. Construction began in 1864.

Elm Park is a Victorian visual delight, in part because of the number of designers who worked on the interiors. LeGrand and Louise acquired works of art for the house and grounds, including two enormous paintings, “Domes of the Yosemite” by Albert Bierstadt, now in the St. Johnsbury Athenaeum, and William Bradford’s “Sealers Crushed in the Icebergs,” now in the New Bedford Whaling Museum. The couple traveled to Europe in 1864 and 1867. In Rome, they commissioned Randolph Rogers to carve a marble sculpture of their two youngest children, now in the museum’s drawing room.

The Lockwoods hired George Platt, an English designer and cabinet-maker, who lived nearby to design the interiors. A letter in the museum archives reveals, though, why other prominent decorators got involved. In Paris in 1867, Louise wrote to her daughter-in-law before a visit to the L’Exposition International, complaining,

Yesterday morning Mr. Marcotte called, having just arrived from America bringing with him, a plan of our library saying that he had received instructions to go on with the furnishing of that room, so I suppose Mr. Platt would not agree to Papa’s terms. I am sorry, and have felt a good deal vexed with Mr. Platt, that he has not written us in the matter, as I could not decide about buying articles for the house until I know something about it.

Platt appears to have been contracted to decorate and furnish the dining room and Louise’s bedroom while Leon Marcotte, formerly in partnership with Lienau, was hired to furnish and decorate the library. The library’s wallpaper was selected from the Pierre Balin booth at the L’Exposition, where Balin had just been awarded a prize. In the library, two painted canvas panels flanked the clock and sculpture above the fireplace executed by Pierre-Victor Galland, decorator for Empress Eugenie and Napolean III of France. Gustave Herter’s New York City company was already working on the interior woodwork of the entrance hall and rotunda; his step-brother, Christian designed the remainder of the formal rooms in a French revival style, plus LeGrand’s bedroom and the guest suite. The architect and decorators artfully integrated new technology into the house, such as hot-air registers and returns, a battery-activated burglar alarm system wired under carpeting to all the exterior doors and windows, gas piping for wall sconces and gasoliers with elaborate rosettes, hot water, cold water, and drinking water and drains for every sink and bathtub, and piping for at least eight flush toilets using water from an attic cistern.

The family moved in in 1868 and then Black Friday arrived on Wall Street in October 1869. The gold market crashed and LeGrand was ruined. He was forced to mortgage Elm Park; he sold his stock in the Lake Shore & Michigan Southern Railroad (as it was now called) to Cornelius Vanderbilt. The family moved to Elm Park full time, but in 1872 LeGrand died suddenly of pneumonia. Louise was forced to sell the art collection at auction and all the furnishings. In 1873 Vanderbilt foreclosed on the house, and Louise and her children moved to New York City.

The family moved in in 1868 and then Black Friday arrived on Wall Street in October 1869. The gold market crashed and LeGrand was ruined. He was forced to mortgage Elm Park; he sold his stock in the Lake Shore & Michigan Southern Railroad (as it was now called) to Cornelius Vanderbilt. The family moved to Elm Park full time, but in 1872 LeGrand died suddenly of pneumonia. Louise was forced to sell the art collection at auction and all the furnishings. In 1873 Vanderbilt foreclosed on the house, and Louise and her children moved to New York City.

In 1876 Charles D. Mathews, a retired dry-goods merchant, and Rebecca Thompson Mathews bought the estate, and spent three years refurnishing it. Charles died of a stroke in 1879 and Rebecca died in 1911. Their oldest son, the New York architect Charles Thompson Mathews, and his sister, Florence Mathews, lived there in the summer until they died in 1934 and 1938, respectively. In 1941 the house was purchased by the City of Norwalk for “park purposes.” The house was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1971.

Mimi Findlay is a trustee of the Lockwood-Mathews Mansion Museum.

Explore!

Lockwood-Mathews Mansion Museum

295 West Avenue, Norwalk

lockwoodmathewsmansion.com

GO TO NEXT STORY

SUBSCRIBE/BUY THE ISSUE!