he Mystic-built William H. Hopkins, nicknamed the “Centennial Schooner,” at dock in Mystic, 1876.

© Mystic Seaport Museum, 1938.537

By Rebecca Bayreuther Donohue

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Fall 2021

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

On a beautiful August day, a party set sail from Mystic, Connecticut aboard the William H. Hopkins for Philadelphia to see the splendors of the 1876 Centennial Exposition. These weren’t the first Mystic residents to make the journey to the exhibition, which had opened in May, nor would they be the last before it closed in November. But they were sailing on a special vessel, built at the famous Greenman shipyard during an era when the phrase “Mystic built,” as identified by historian William N. Peterson in “Mystic Built”: Ships and Shipyards of the Mystic River, Connecticut, 1784-1919 (Mystic Seaport Museum Inc., 1989), symbolized remarkable speed and beauty the maritime community.

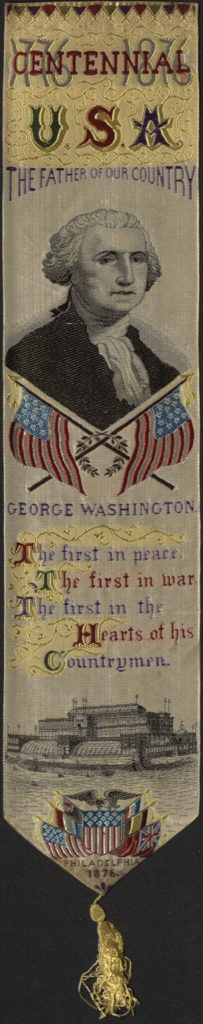

Commemorative bookmark owned by the Greenman family, builders of the “Centennial Schooner.” © Mystic Seaport Museum, 1994.123

1876 marked an enormous turning point for the United States as it celebrated its first 100 years of independence from Britain. The Centennial Exposition was planned as a major part of that celebration, but it was set against the backdrop of political upheaval. Journalist Erin Blakemore, on Nationalgeographic.com (January 5, 2021), called the year’s presidential election between Ohio’s Governor Rutherford B. Hayes (R) and New York’s Governor Samuel J. Tilden (D) “the most divisive in U.S. history.” Hayes’s shady electoral college victory brokered the end of federal enforcement of Reconstruction in the South.

Mystic was changing, too. During the next few years, most of the major shipyards closed or dwindled to boatyards under the dual weights of advancing age and technology. As historian Carol W. Kimball remarked in “Centennial Schooner” (Log of Mystic Seaport, Marine Historical Association, 1968), William H. Hopkins was the last sailing ship built by Geo. Greenman & Co.

On Christmas Eve 1875, the Mystic Press announced “the building of a large schooner to be completed before the opening of the Centennial.” As it happened it was mid-June before the 134-ton vessel was in the water ready to receive her three masts, her rigging, and the donkey engine that would drive her windlass. Her official name was the William H. Hopkins (origin of the name is unknown), and her official use was to sail in the coal trade. But first, she was given a different mission: berths for 150 were installed to accommodate travel to the Centennial Exposition. A round-trip passage plus onboard accommodations during her week at the exposition cost just $10.

She was dubbed the “Centennial Schooner” everywhere from in the press to the Greenman shipyard account books, and she sailed in August with just shy of 60 passengers. The affordable rate of passage attracted an eclectic group, including recent high school graduates, their teachers, Civil War veterans, and two little boys both named Willie, according to the passenger manifest. Fully one-third of the passengers were in their teens or early twenties. A large contingent represented the Union Baptist Church, from the established Bridget Gallup Rathbun Potter and her husband Deacon William Potter, celebrating the 30th year of his work in the church, to young Francisco Sebastian, a sailor of Brazilian and Eastern Pequot descent who, though sailing alone, had just celebrated his third wedding anniversary with Shinnecock tribal member Mary McKinney.

Lucius Guernsey, the Press editor, documented the voyage, describing everything from the musical entertainments to an infestation of “Jersey sharps” mosquitoes. He gleefully noted each time the schooner outsailed another vessel, from New York to Delaware Bay and back again. And he summed up the experience in the warmest of phrases: “Thus ended the outward passage of the good schooner WM. H. HOPKINS, a trip, which though short in duration, was to many on board one of the pleasantest episodes of their life. …We started a heterogenous company—we arrived a happy family.”

Although plenty of Mystic residents made the journey to Philadelphia—the Press quipped in October that “we had better wait, and when it’s over, publish the names of the scattering few who don’t go”—the “Centennial Schooner” only made one trip. A second charter fell through, and by the end of August the yard was busily refitting the vessel for her original purpose.

Rather than regret for the Hopkins’s single voyage, however, a sense of satisfaction prevailed at having launched a voyage at all. Mystic’s proud shipbuilding legacy had been on living exhibit at the most spectacular celebration this young country could invent. Throughout the rest of the year, the Press continued its unstinting praise for the schooner’s Mystic-built lineage, reporting that “The Hopkins is proving herself one of the best sailers on the coast, making the trip from New York to Philadelphia … in 28 hours, returning … to New London in 38 hours.” The village of Mystic would ultimately prove herself a good “sailer” as well, weathering multiple storms to emerge once again as a haven of wooden ship- and boat-building in the 20th century.

Rebecca Bayreuther Donohue is a Niantic-based historian who interpreted maritime history at Mystic Seaport Museum for more than 20 years. She last wrote “The Sooner Home the Better,” Spring 2009.

GO TO NEXT STORY

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!