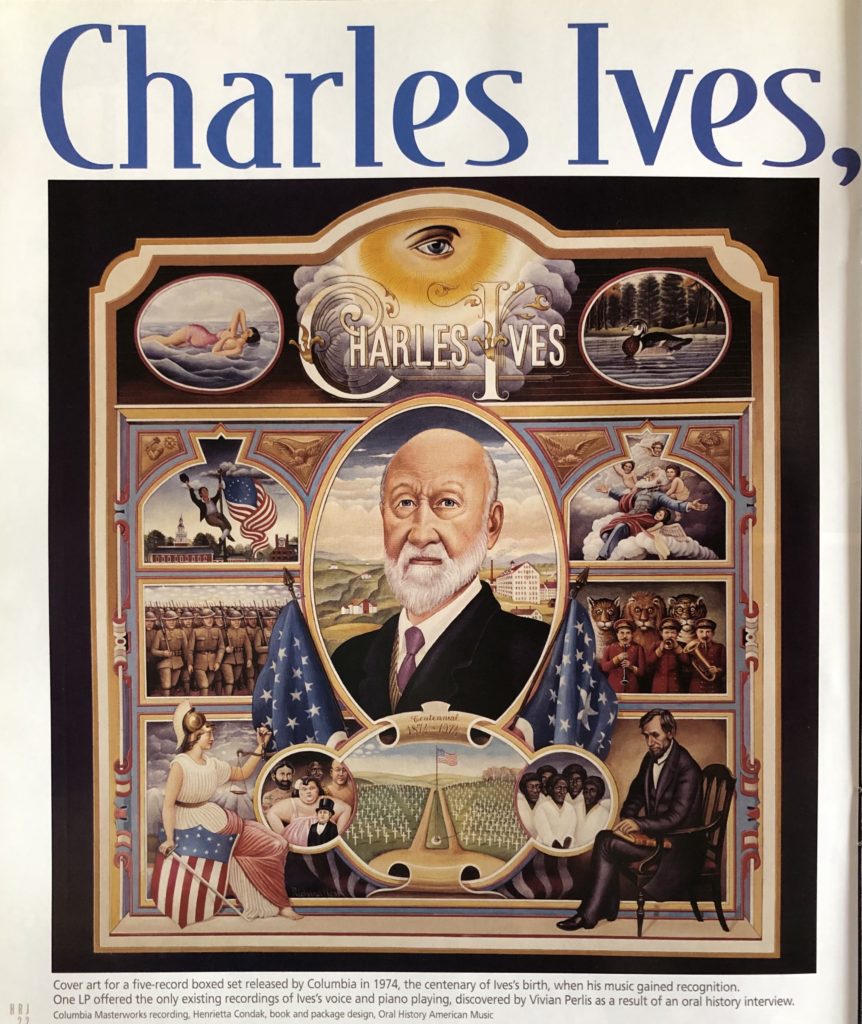

Cover art for a five-record boxed set released by Columbia, 1974. Columbia Masterworks recording, Henrietta Condak, book and package design, Oral History American Music, Yale University

By Libby Van Cleve

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Fall 2008

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

The brilliant innovative composer Charles Ives is widely considered the father of American experimental music. Ives was a true product of Connecticut: he was born in Danbury in 1874, educated at Yale, and lived in West Redding. While a student, he held a position as organist for New Haven’s Center Church on the green, and he even named a movement from his important orchestral work Three Places in New England after the Revolutionary War General Israel Putnam’s camp near Redding. Ives won a Pulitzer Prize, and his work is esteemed by musicians and scholars. Yet this remarkably imaginative composer’s music is still not well known by the general public.

When Ives was growing up in Danbury, it was a small town primarily noted for manufacturing men’s hats, but the townspeople enjoyed an active musical life. Ives’s father, George, as the town bandmaster, was considered the best all-around musician in the area. Charlie’s natural talent, perhaps inherited from his father, was nurtured by George as soon as his boy showed an interest in music. Around town, Charlie was simply his father’s son, following in Dad’s footsteps. If he was known for anything special, it was for his baseball playing. He was shy, perhaps ashamed, about his music. According to the Ives expert John Kirkpatrick, when Ives was asked about what he played, he responded: “shortstop.” At that time, music was entertainment, not a serious occupation, and Charlie must have perceived that his father’s work was not admired by the family or the town. The male members of the respectable Ives family were meant to be lawyers or businessmen; music was a nice hobby for women and girls.

George Ives, however, was not an ordinary musician. He had a vivid imagination and was interested in sounds and how they changed in reaction to various conditions. He experimented with space: a horn sounded over water or from a church tower, a fire truck’s bells, and bands playing different tunes as they marched toward each other from opposite directions. He built his own instruments that made sounds different from the norm, like an ironing board on which he stretched 24 strings to make a violin that could produce quarter-tones. He brought his family into his experiments, teaching them to “stretch their ears”; he would have them sing “Swanee River” in one key while he played it in another. As the major influence on his gifted son, George made sure his boy had a solid music education, but he left the door open to the many places music could go beyond the traditional pathways. Charlie absorbed everything his father taught him, and either took part in or witnessed his father’s diverse activities in the music world Danbury, including forays with band, church, gospel, ragtime, and theater.

The younger Ives also absorbed his father’s natural leaning toward Transcendentalism. For example, George responded to complaints about a local workman’s singing terribly off-key, saying: “Look into his face and hear the music of the ages. Don’t pay too much attention to the sounds—if you do, you may miss the music. You won’t get a wild, heroic ride to heaven on pretty little sounds.” Transcendental philosophy, particularly as Charles learned it from his father and the writings of philosopher and poet Ralph Waldo Emerson, was to be central to Ives’s thinking throughout his life.

When Charlie was 14, the local paper noted he was the youngest organist in the state. By the time Ives went to Yale (where he graduated with the class of 1898), he had years of performing experience, and as a composer he had already written a number of marches and other short pieces. Notable among them was Variations on “America” for organ, which included several interludes written simultaneously in two keys, composed when Ives was only 17.

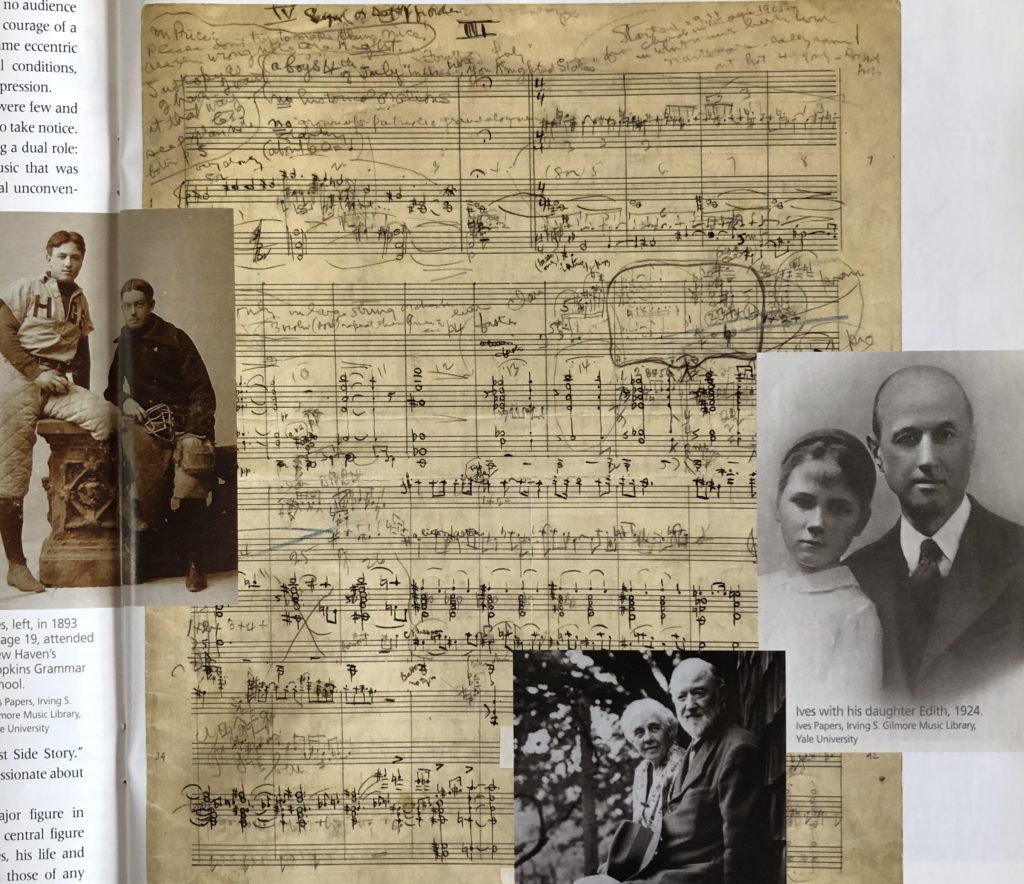

Left: Charles Ives (left) at age 19, 1893. center: Manuscript for “The Fourth of July,” a movement from A Symphony: New England Holiday, c. 1918. bottom: Ives with his wife Harmony, West Redding, c. 1948; right: Ives with his daughter Edith, 1924. Ives Papers, Irving S. Gilmore Music Library, Yale University

With the death of his father during his freshman year at Yale, Ives lost his strongest supporter. His subsequent studies with the celebrated Yale professor Horatio Parker fell short of success. It has been said that Ives was writing his father’s music, which must have not held up well under Parker’s conservative approach. Ives soon learned to keep his more adventurous compositions away from the classroom. To graduate from Yale, Ives composed his first symphony in compliance with Parker’s rules and suggestions.

After graduation Ives went to New York City to find his way in the world of commerce. He decided he would avoid the humiliation of working in the music profession that his father had endured. He applied his intelligence and imagination to the insurance business but continued to compose music at night and on weekends. Ives always insisted that his work in business helped his music, and his music helped his business.

In the first three decades of the 1900s, Ives composed an extraordinary amount of music, much of it anticipating developments to come later in the century. His innovations include multi-layering of unrelated music ideas, use of unusual instruments, quotation of a wide range of musical material, and experimentation with polyrhythm, polytonality, microtonality, and spatial music. Considering that he held a demanding full-time position as partner in the insurance offices of Ives & Myrick, the scope and size of his output is impressive. His catalogue includes large orchestral works, chamber orchestra pieces, keyboard works culminating in the two large-scale sonatas, and more than two hundred songs. The songs alone are a huge achievement and have been described as the greatest collection of art songs by an American composer. (See Sidebar on the Ives Vocal Marathon.) Ives did not, however, completely abandon tonality or established forms. Some of his songs are traditional, harking back to the sentimental ballads of post-Civil War America. He used whatever music imagery he could that would best serve to conjure the image of an idea, place, or person in music.

In 1908 Ives married Harmony Twichell, daughter of the Reverend Joseph Twichell of Hartford’s Asylum Hill Congregational Church. She was considered a great catch and referred to as “the prettiest girl in Hartford.” The young couple lived in New York City; in 1912 they built a country place in West Redding, Connecticut. Three years later they adopted a daughter, Edith.

Outwardly, Ives was a successful family- and businessman. Inwardly, he was a frustrated composer with big ideas and important things to say—but without an audience to hear them. Between 1902, when Ives gave up playing church organ, and 1925, when his “Three Quarter-tone Pieces” were performed by Pro Music at New York’s Town Hall, there were virtually no public performances of Ives’s music.

By 1920, when he was 46 years old, Ives was disabled by illness that had plagued him since about 1908. He could no longer compose. What energy he had was directed toward revising scores and privately publishing and distributing his “Sonata No.2: Concord, Massachusetts, 1840-60” and “114 Songs.” Aaron Copland wrote, “how I wondered, does a man of such gifts manage to go on creating in a vacuum, with no audience at all… . To write all that music and not hear it one would have to have the courage of a lion.” Ives had the courage, but neglect and criticism took their tool. If Ives became eccentric in his later years, he had good reason. He suffered from various physical conditions, including diabetes. He also showed signs that are symptomatic of underlying depression.

Things slowly began to turn around for Ives and his work. Performances were few and far between, but younger composers and a few supporters of new music started to take notice. Ives became part of the movement for modern music after World War I, playing a dual role: as patron, he financed many new music efforts; as composer, he wrote music that was performed by the groups he supported. Ives attracted the admiration of several unconventional figures, among them the innovative composers Henry Cowell, Lou Harrison, and Carl Ruggles; the scholar and performers John Kirkpatrick; and the conductor and lexicographer Nicolas Slonimsky.

Through the valiant efforts of these and a few other younger composers and performers, the public finally began to pay attention to Ives. John Kirkpatrick’s performance of the “Concord Sonata” in 1939 at New York’s Town Hall was a landmark in Ives’s career. Lou Harrison’s conducting the Third Symphony in 1946 (the composition for which Ives won the Pulitzer Prize in 1947) was another. Leopold Stokowski’s attention to the Fourth Symphony and Leonard Bernstein’s to the Second Symphony were highlights that shone all the brighter in the dim atmosphere surrounding public acceptance of Ives and innovative music in general.

top: Ives Papers, Irving S. Gilmore Music Library, Yale University. bottom: Oral History American Music, Yale University

By the time of his death in 1954, Ives was gradually gaining recognition as a composer, but to most of the public he remained an obscure figure. He had spent the last years of his life in seclusion. Many who had known him were themselves growing old and fragile. It seemed that much information about this seminal American composer would be lost. About 15 years later, though, an oral history project was initiated to illuminate and preserve many details of Ives’s life and career.

Today, 30 years after completion of the Ives oral history project, Charles Ives remains an enigma. Performances and recordings have become more common, increasing public awareness of his work, but his music is still not considered mainstream. The experimental pieces still sound “modern” to audiences, who continue to be perplexed. “The Unanswered Question” and “Three Places in New England” are programmed frequently, but they do not reach as broad a public as does, for example, Copland’s “Fanfare for the Common Man” or Bernstein’s “West Side Story.” Ives remains an acquired taste, and as with such tastes, those who have it are passionate about it, while those who do not are in the majority.

Whatever his image with the general public, Ives’s status as a major figure in the history of American music is assured. He is universally recognized as a central figure bridging the 19th and 20th centuries. Since the earliest publications on Ives, his life and works have been examined, dissected, discussed, and published more than those of any other concert composer in American music history.

Libby Van Cleve is associate director of the Oral History American Music Project (OHAM) at Yale University. She is co-author of Composer’s Voices from Ives to Ellington (Yale University Press).

Explore!

Read more stories about Connecticut art, theater, music, and literary history on our TOPICS page.

Read about other Notable Connecticans on our TOPICS page.