(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Fall 2006

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

The Colt Armory fire of 1864 embodied all the characteristics of a modern conspiracy thriller. It occurred in a factory producing needed war materiel and spread with lightning speed. These conditions, combined with the fact that the armory’s water reservoirs, intended for fighting fires, were dry and the cause of the fire unknown, immediately gave rise to rumors of arson or sabotage. Yet in many respects it was typical of any industrial fire.

Upon its completion in early 1856 the Colt’s Patent Fire Arms Manufacturing Company’s three-story armory dominated the skyline immediately south of Hartford. Measuring some 500 feet in length with a width of 60 feet, the armory physically reflected both the wealth of its builder, Samuel Colt, and the prosperity of his business. Shortly after the beginning of the Civil War, the armory was substantially enlarged by the addition of a matching building located on the western side of the original.

Though the company was ostensibly a public firm, the majority of its stock was held by Samuel Colt. Following his death at age 47 in January 1872, control passed to his widow, Elizabeth Hart Jarvis Colt (1826 – 1905). Minority stock holdings were held by various relatives and trusted associates of the late owner, but none of these was significant enough to affect Elizabeth’s decisions. Mindful of her late husband’s wishes, she appointed the factory’s superintendent, Elisha K. Root, as president as her brother Richard Jarvis as vice president. These two men were to guide the firm’s operations throughout the war.

A Sudden Blaze

The first indications that something was amiss were noticed about an hour and a quarter after the February 4, 1864 shift had begun work at 7 a.m., when workers outside the armory spotted smoke wafting from an attic ventilation window near the southern end of the structure’s riverside wing. Employees within the works were immediately dispatched to the attic, and hoses were brought up to douse the fire, However, having discovered the company’s water reservoirs were dry, the workers were forced to flee when the fire exploded from a room used to dry wood for pistol and rifle stocks and ignited the leather pulley belts that drove the machinery in the floors below.

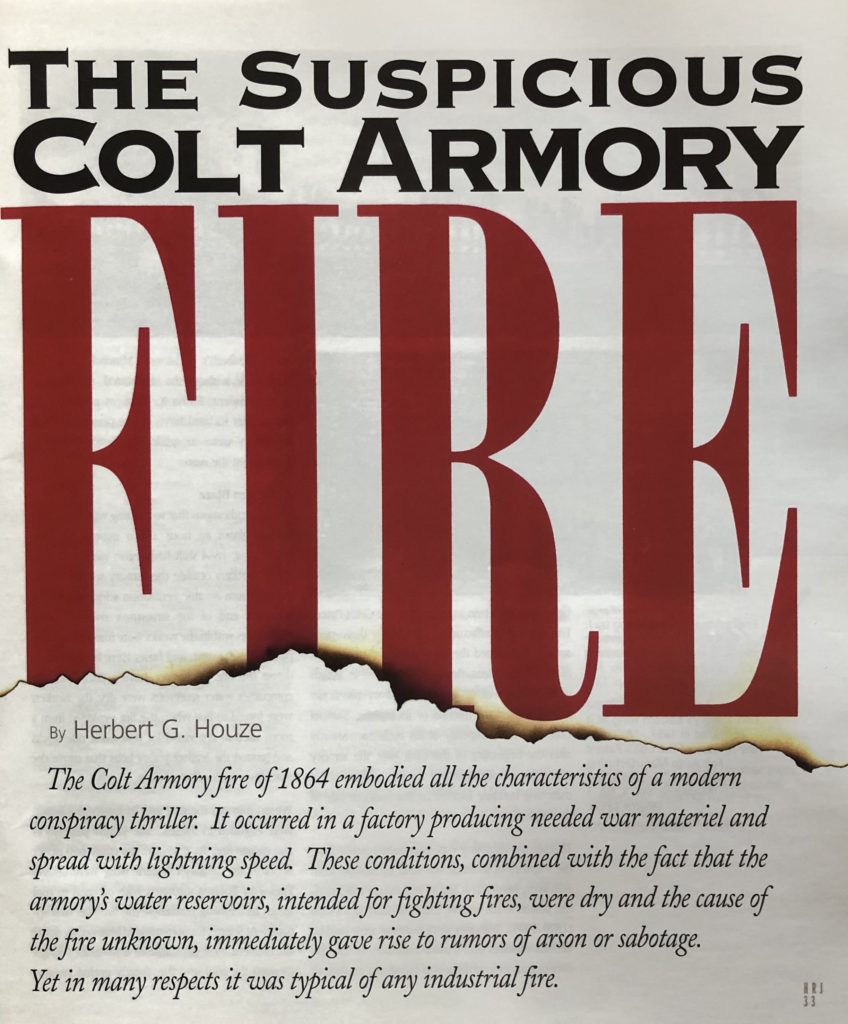

top: Engraving after a drawing by J. B. Russell, Jr. of the armory fire at its height. Harper’s Weekly, Vol. VIII, No. 373 (February 20, 1864), p. 125. bottom: An interior view of the Colt armory’s eastern wing as it appeared in 1857. “A Day at the Armory of the Colt’s Patent Fire Arms Manufacturing Company.” United States Magazine, Vol. 4, No. 3 (March 1857).

Within minutes the roof and its supporting beams were engulfed in flames. The yellow pine floors also caught fire. By 8:45 a.m. the entire two upper floors of the armory’s eastern wing were ablaze. Fueled by flooring saturated with oil used to cool lathes and milling machines, the fire was unstoppable. At 9 a.m., the star-studded blue onion dome surmounted by a gilt statue of a rampant colt fell through the roof into the already gutted interior. Soon the fire spread from the eastern wing by a covered bridge to the armory’s office building. This building too would be lost.

By mid-morning, less than two hours after smoke had first been seen, the front half of the armory was a flaming ruin.

The powerhouse and several less important buildings were lost, but the factory’s workers and the volunteer Hartford Fire Department managed to prevent the fire from engulfing the west wing, where rifle muskets were being made. Completely destroyed, though, were the areas devoted to producing pistols and revolving rifles, severely crippling the factory’s future output.

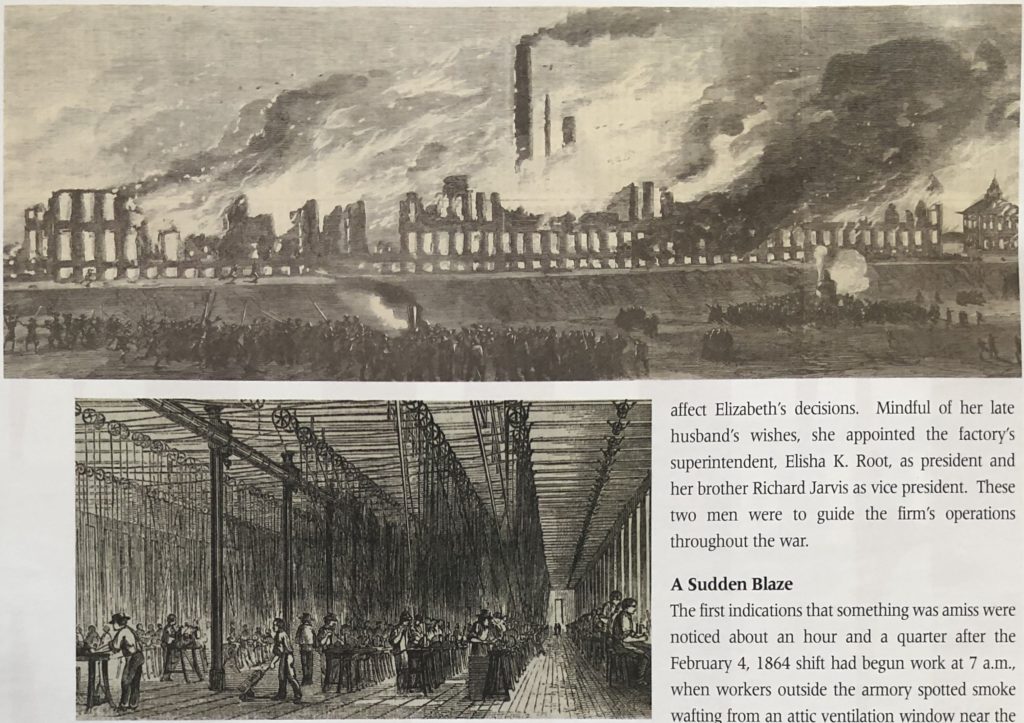

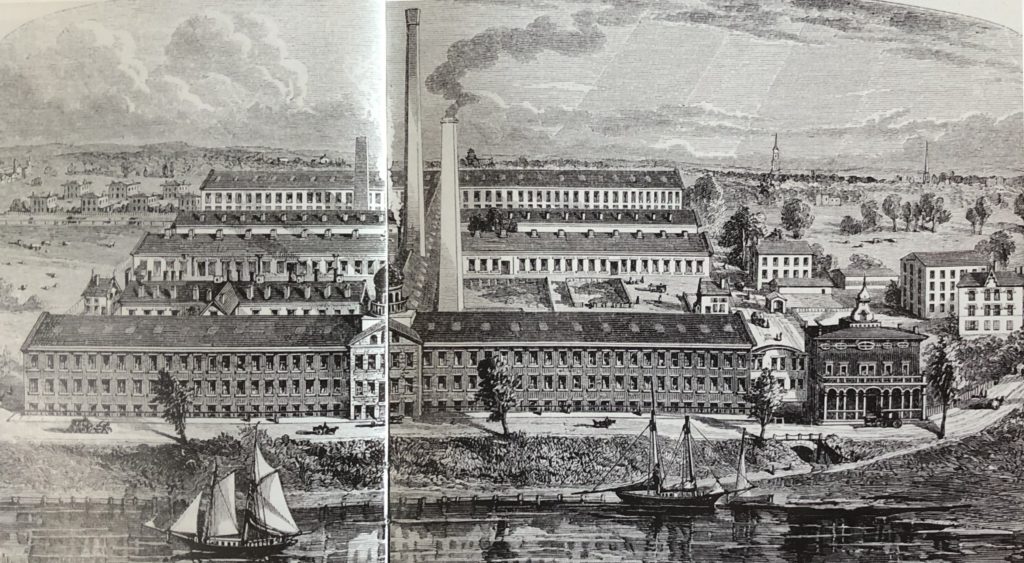

inset: Engraving of the Colt’s Patent Fire Arms Manufacturing Company’s Hartford factory c. 1857. The portions destroyed in the 1864 fire were the eastern or riverside wing, the office building to the right, and the power plant located by the chimney to the rear. “A Day at the Armory of the Colt’s Patent Fire Arms Manufacturing Company,” United States Magazine, Vol. 4, No. 3. (March 1857). Below:

The Colt armory after the fire of February 4, 1864. Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art

Colt’s workmen behaved with great calm and, in some instances, considerable heroism throughout the early stages of the fire. When it became apparent that the conflagration could not be contained, employees began removing whatever tooling and essential machinery they could. It was during this process that E. K. Fox, the only fatality, lost his life. After retrieving numerous items, he had returned to the victory for more when he was trapped by the collapse of the second floor. Before the office caught fire, workers threw as many records as they could out of its windows, saving troves of corporate documents and correspondence.

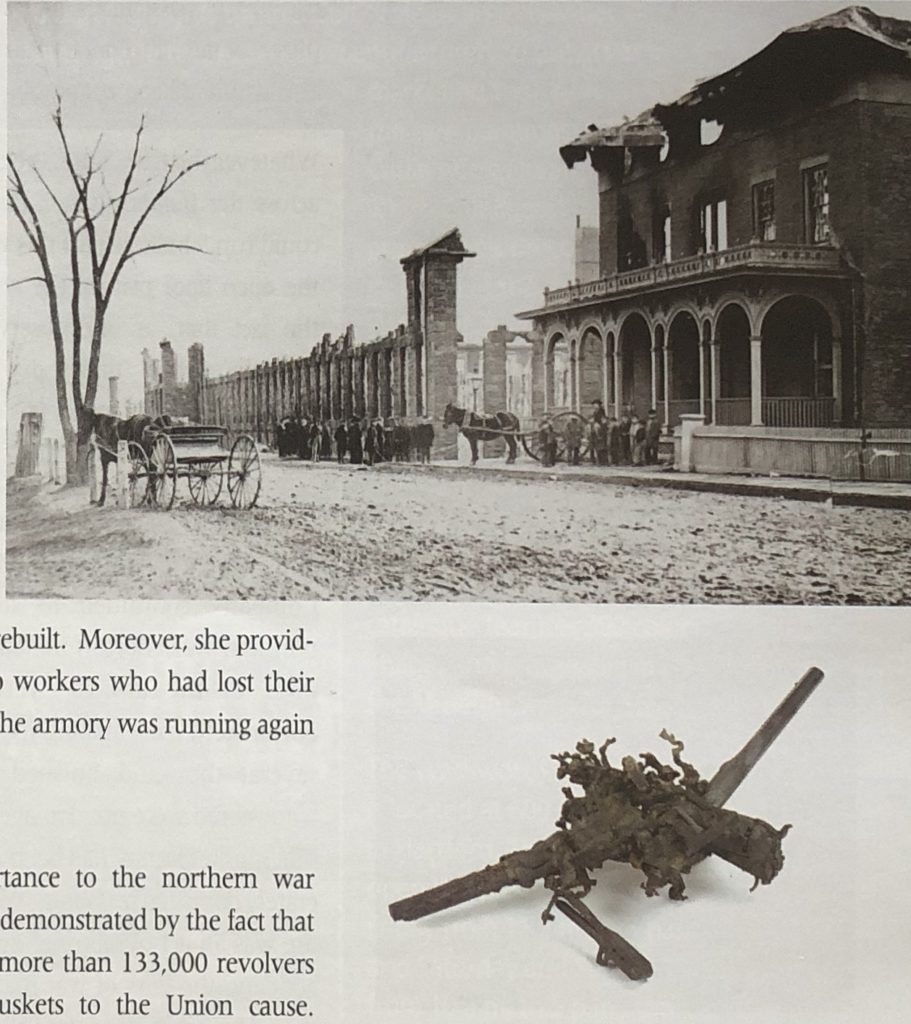

The fire was essentially contained by noon on February 4, though it would not be completely extinguished for two days. Photographs taken immediately thereafter illustrate the extent of the devastation. The eastern wing and the factory’s office building were just shells, and all the machinery that had been in place on the factory’s floors was a mass of jumbled iron in what had been the basement. A fused conglomeration of revolver parts recovered from the site demonstrates the severity of the heat generated by the fire. Workers recovered this hunk of metal, consisting of iron bullet molds, loading rods, miscellaneous pistol parts, and complete revolvers. Elizabeth Colt kept it as a remembrance of the calamity.

Enormous Losses

In all, more than a thousand lathes and milling machines were lost. The plant’s primary power sources, two 300- and 400-horsepower engines, were destroyed, as was the main boiler. Factory officers estimated that at least a million dollars’ worth of work in progress, as well as tooling and buildings worth roughly that same amount, had been consumed. Not counted in this assessment were the employees who had lost their jobs and the personal tools of their respective trades.

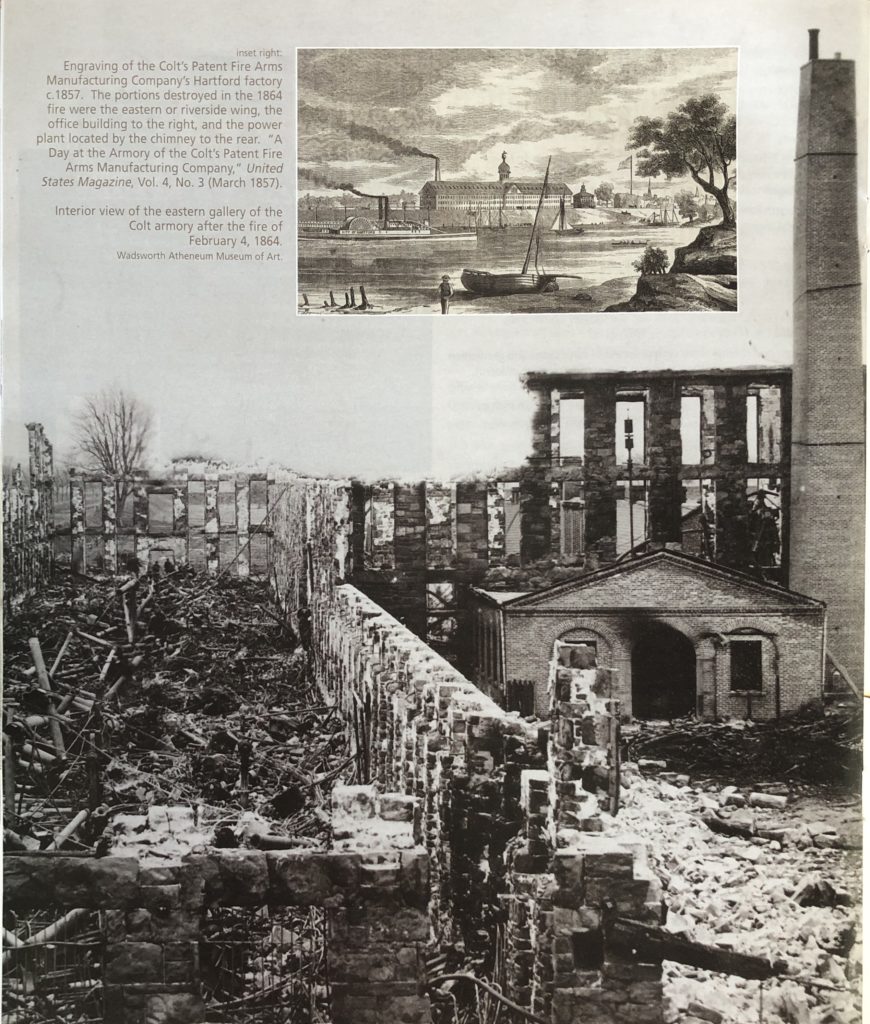

Perhaps more frightening to the concern’s owners was the fact that the factory had only been insured for $600,000. While one of less fortitude might have walked away at this point, Elizabeth Colt ordered the armory rebuilt. Moreover, she provided funds to re-equip workers who had lost their tools. By late 1866, the armory was running again at full capacity.

top: View of the remains of the Colt Company’s office and eastern wing facade after the February 4, 1864 fire. Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art. bottom: A mass of fused revolver parts, accessories, and completed pistols recovered from the ruins of the Colt armory. Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art

Mysterious Cause

The armory’s importance to the northern war effort is perhaps best demonstrated by the fact that the factory supplied more than 133,000 revolvers and 96,500 rifle muskets to the Union cause. Consequently, when the armory was partially destroyed by fire in February 1864, suspicions about the blaze’s cause were immediately raised.

In the days that followed the fire many theories were advanced. The first suggested that a build-up of friction in the main drive pulley that supplied power to the eastern wing’s machines was to blame. This notion was quickly discounted, however, as the pulley, which in any case had been lubricated the morning of the 4th, ran in a heavy iron conduit that would have prevented a flash-over. THe first workers to reach the attic after smoke was discovered stated the fire was located in a room where pistol grips were dried. While this room was heated by steam, which couldn’t have sparked a flame, some suggested that cotton waste used for polishing and packing-crate excelsior stored there might have been the culprits.

Yet no one could explain why these materials would have spontaneously combusted. This in turn gave rise to the possibilities that a Confederate sympathizer or an “incendiary” (a politically motivated arsonist) had been responsible.

Whatever the true cause, the fire “swept across the building faster than a man could run.” In large part this was due to the open floor plan of the armory and the fact that, as one observer noted, everything was “tinder dry.” As a result, the fire’s progress was essentially uncontrollable.

Despite the massive destruction the Colt’s Patent Fire Arms Manufacturing Company continued to supply the northern war effort as the affected sections of the armory were rebuilt. Fortunately, the shipping rooms where several thousand finished revolvers were stored were not damaged, and the rifle musket facility had been only moderately damaged by water. Whether the fire was an act of sabotage or purely an accident, the flow of war materiel from the Colt Company to the Union continued unabated.

As this 1867 engraving illustrates, the rebuilt Colt armory mirrored the factory erected by Samuel Colt more than a decade earlier. Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art

In an ironic twist of fate, the fire proved to be a godsend to the Colt Company. Since Elizabeth Colt had banked most of the money she had received as the firm’s principal owner since her husband’s death, she was able not only to rebuild the factory but also to install the latest machinery. As a result, when the Colt’s Patent Fire Arms Manufacturing Company restarted pistol production, it used all new machinery, while its competitors continued using tooling that had been run almost to the point of exhaustion during the Civil War. This gave Colt’s concern a tremendous advantage that was to be fully exploited in the years that followed.

Herbert Houze is a firearms historian and author of numerous reference works on the subject. He is currently guest curator for the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art’s exhibition Samuel Colt: Arms, Art and Invention.

Note: the primary sources for this article are in the accounts of the fire published initially in The Hartford Courant on February 5, 1864 (p. 1) and later in The New York Times on February 7, 1864 (p. 1). The quoted material was extracted from the report that appeared in the Times.

COLT EXHIBITION ON VIEW AT WADSWORTH ATHENEUM

The Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art presents Samuel Colt: Arms, Art, and Invention September 20, 2006 through March 4, 2007. The exhibition and accompanying catalogue — written by guest curator Herbert Houze — are the first to document the Atheneum’s unsurpassed collections of Colt firearms. The show features rare handguns that were in Samuel Colt’s armory office at his death in 1862, including prototypes and examples of his manufactured designs along with 17th- and 18th-century pieces that demonstrate how far Colt advanced revolver design. The show also features the collection of firearms assembled in 1863 by Colt’s widow, Elizabeth Hart Jarvis Colt.

Beyond the firearms themselves, the exhibition highlights Samuel Colt’s role as an influential figure in 19th-century America. For instance, he was among the first American manufacturers to use art as a marketing tool. At least six of the rare paintings in George Catlin’s Colt Firearms Series, which Colt commissioned to promote his products, are included in the show. The exhibition traces the development of revolving firearms, showcases Colt’s distinctive craftsmanship and design, and explores his use of mass production.

The 352-page exhibition catalogue features 300 color images and is available in the museum shop for $65.

The Wadsworth Atheneum

600 Main Street, Hartford

(860) 278-2760

thewadsworth.org