Witness to Gettysburg: Horatio Dana Chapman

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. 2003 Nov/Dec/Jan 2004/ Vol 2, No. 1

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

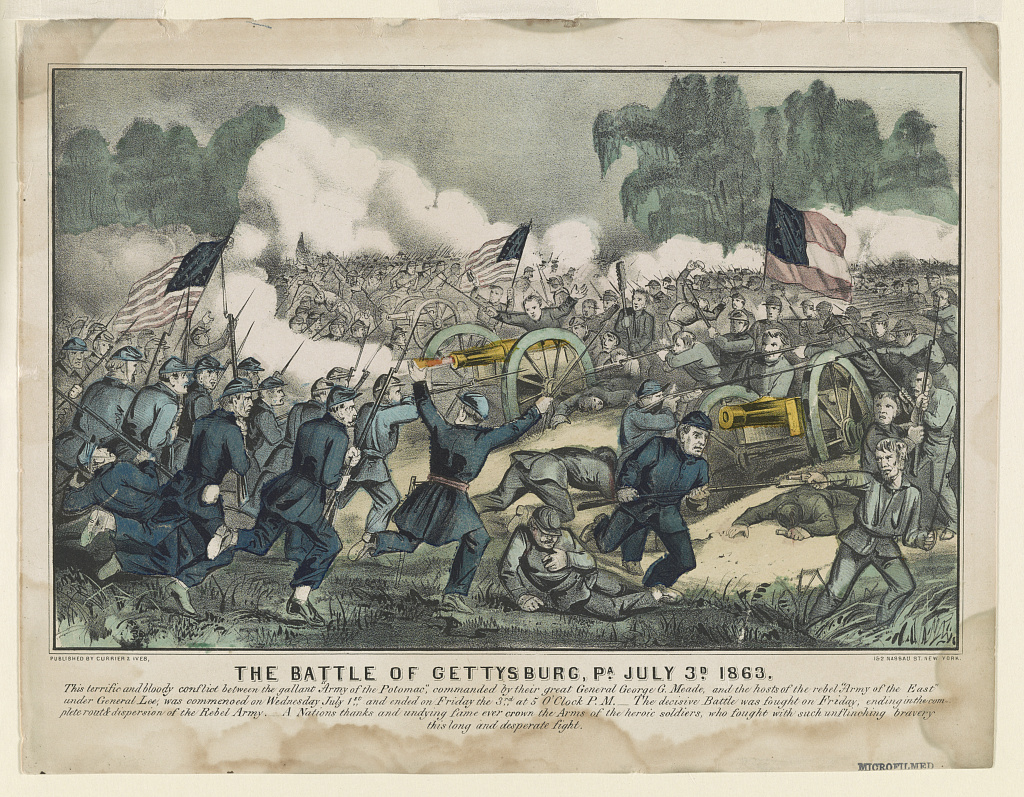

Horatio Dana Chapman (1826 – 1910), of East Haddam and East Hampton, enlisted in the army on August 6, 1862, and served in the Twentieth Connecticut Volunteers. He was 36 when he enlisted. He fought at Chancellorsville (April 30 – May 6, 1863, a Confederate victory) and Gettysburg two months later (July 1 – 3, 1863.) The Battle of Gettysburg was a Union victory and a turning point in the war.

The following diary excerpts describing the Battle of Gettysburg are taken from Civil War Diary—Diary of a Forty-Niner by Chapman, published posthumously in Hartford by Allis Publishing in 1929. The book and original diary are in the collection of the Connecticut State Library.

Note: Paragraph separations have been added for ease of reading.

June 30, 1863. We have been marching quite rapidly all day and sometimes at a double quick. It is again reported that Lee’s army is north of us and has entered the state of Pennsylvania and that the advance of our army is very near the Confederate army, and that before long the two armies will meet and in all probability a terrible battle will ensue, and I am willing with thousands and tens of thousands of others of my fellow soldiers to do, to dare, to sacrifice and suffer, if by any means this war will be brought to a termination. We hope to capture or so cripple the Confederate army here on northern soil that the South will give up the contest and an honorable peace be restored. But time will determine.

July 1. Resumed our march at an early hour in a northly direction and marched rapidly all day and encamped for the night. Nothing of any particular importance transpired this day.

July 2. Were ordered to fall in at an early hour this morning and to forward march. The booming of cannon was heard, apparently several miles distant from us in a northerly direction, and we were pretty sure that the advance of our army had engaged the enemy. The booming of cannon as we advanced became more and more rapid and we were ordered at a double quick which we continued at intervals until noon, when we came upon the scene of action in the State of Penn., near the Town of Gettysburg.

We were immediately formed in line of battle on the extreme right of our line on Culp’s Hill and commenced throwing up breastworks in our immediate front, and about 5 p.m. we had a very good protection from the bullets of the enemy. As yet there had been no fighting on this end of the line. But on the left and left center the battle had been raging with great fury by both infantry and artillery, and especially the left center of our army was being hardly pushed by the enemy.

Our brigade, consisting of the 5th and 20th Connecticut, 3rd Maryland, 46th Pennsylvania, 123rd and 145th New York, were ordered to leave our breastworks and go to their support and we started on a double quick. We were shelled by the rebels but not turned back. We met some battery boys on the retreat, among whom was Cousin Frank. He told hurriedly that our army was defeated, that they had killed a great many of their horses, knocked their battery into a cocked hat and taken some of the battery boy prisoners. They seemed to be somewhat panic-stricken but were somewhat reassured when they saw so many of our soldiers passing to the front where they were fleeing from.

The battery was re-taken with a good many rebel prisoners, and our brigade was ordered back to our breastworks. It was now quite dark. When we were within twenty or thirty rods of our breastworks, a volley of musketry was poured into our ranks from our immediate front and we came to a halt instantaneously in a cornfield, and some of us went forward to reconnoiter very cautiously, and found that the rebels had taken possession of our breastworks in our absence and were of course securely [e]ntrenched behind them.

The battery was re-taken with a good many rebel prisoners, and our brigade was ordered back to our breastworks. It was now quite dark. When we were within twenty or thirty rods of our breastworks, a volley of musketry was poured into our ranks from our immediate front and we came to a halt instantaneously in a cornfield, and some of us went forward to reconnoiter very cautiously, and found that the rebels had taken possession of our breastworks in our absence and were of course securely [e]ntrenched behind them.

It was of no use to attempt anything by way of re-taking them in the darkness, and we spent the night as best we could in the muddy cornfield. A little incident in the night happened in this wise: as it was very warm and we all were quite thirsty, a few of us had permission to take a few canteens and go to a large spring, near our breastworks, where we had gotten water when we were building it in the afternoon. There were quite a large number at that spring and it was so dark that we could not tell who was or which from t’other, and although all was still and not a word spoken, yet we well knew that they were rebels, and they also knew that the Yanks were there. We filled our canteens and returned, much to the joy of our thirsty comrades.

July 3. About 3 this morning, as it began to grow light, a strong skirmish line was formed and we were ordered forward and to align ourselves and go slowly and cautiously, and see if we could retake our works. After going through a strip of woods we came to an opening beyond which were our works. About four or five rods from our breastworks the rebels had also a strong line of skirmishers.

We poured a volley into them and it was returned vigorously and the firing along the whole line of skirmishers became more and more rapid and incessant. In about an hour as there had been no advance on either side by the skirmishers from the position first taken, although some were killed and many wounded on both sides, a second line of rebel skirmishers more numerous than the first came over the breastworks and joined their first line and advanced rapidly upon us. We were forced to retreat as fast as possible back through the woods.

We went and met our brigade advancing in line of battle. One volley was poured into them and it checked them instanter and they about faced and retreated, leaving many dead and wounded. We continued to advance, passed their dead and wounded until within short range of our works, and from our own breastworks, which was now their protection, they poured such a withering fire into our ranks and which was followed by volley after volley that our brigade was forced to retreat back through the woods and out of range of their musketry; and so it was a continued fight of advance and retreat, advance and retreat.

The rebels were in large force behind these works which we had built for our own protection and we could not start them, and so the fight continued until about 3 in the afternoon, the dead and wounded on both sides mixed together indiscriminately. All at once it seemed as if all the artillery in the universe had opened fire and was belching forth [missiles]of death and destruction to friend and foe. The thundering of the artillery was rapid and loud on both sides and the solid shot and shells of both armies going over our heads, the infantry enjoyed a state of rest.

For two or three hours this terrible artillery warfare raged and then the guns of the enemy began to slacken and ours to grow less and less—and then ceased altogether—and we were ordered forward and continued to advance up to our breastworks and took possession, not a rifle being fired, the rebels having retreated, leaving their dead and wounded on the field of battle. Pickets were thrown out in front and a strong body behind our works, to guard against surprises during the night.

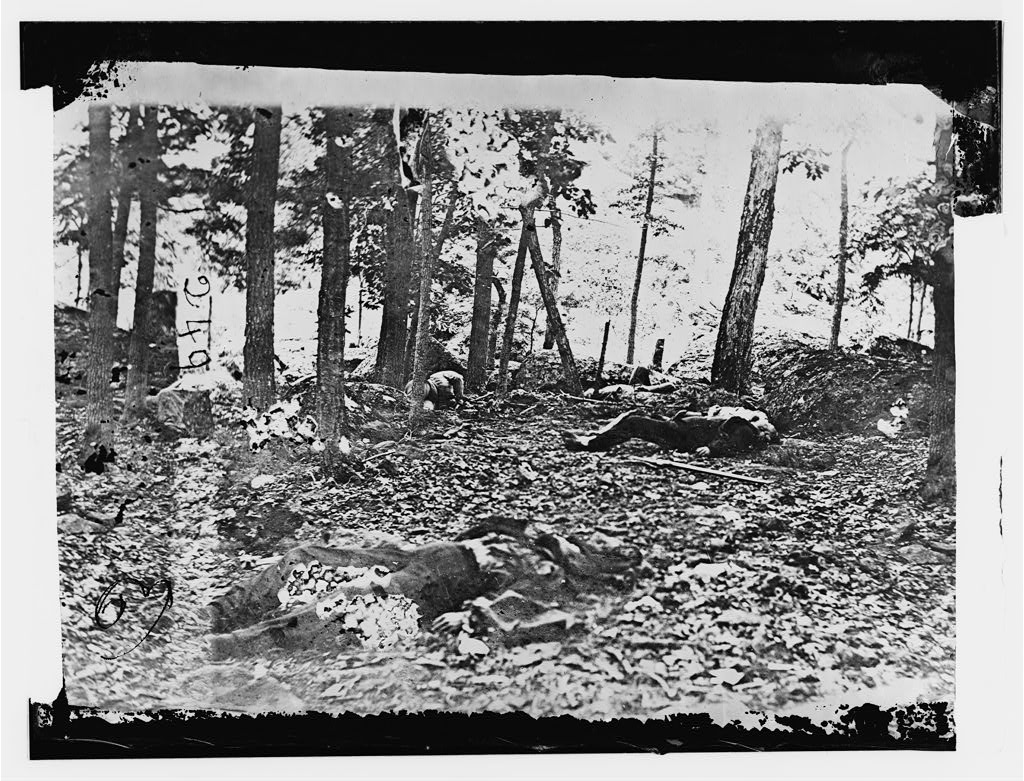

We built fires all over the battlefield and the dead of the blue and gray were being buried all night, and the wounded carried to the hospital. We made no distinction between our own and the Confederate wounded, but treated them both alike, and although we had engaged in fierce and deadly combat all day and [were]weary and all begrimed with smoke and powder and dust, many of us went around among the wounded and gave cooling water or hot coffee to drink. The Confederates were surprised and so expressed themselves that they received such kind treatment at our hands, and some of the slightly wounded were glad they were wounded and our prisoners.

But in front of our breastworks, where the Confederates were massed in large numbers, the sight was truly awful and appalling. The shells from our batteries had told with fearful and terrible effect upon them and the dead in some places were piled upon each other, and the groans and moans of the wounded were truly saddening to hear. Some were just alive and gasping, but unconscious. Others were mortally wounded and were conscious of the fact that they could not live long; and there were others wounded, how bad they could not tell, whether mortal or otherwise, and so it was they would linger on some longer and some for a shorter time—without the sight of consolation of wife, mother, sister or friend.

I saw a letter sticking out of the breast pocket of one of the Confederate dead, a young man apparently twenty-four. Curiosity prompted me to read it. It was from his young wife way down in the state of Louisiana. She was hoping and longing that this cruel war would end and he could come home, and she says, “Our little boy gets into my lap and says, ‘Now, Mama, I will give you a kiss for Papa.’ But oh how I wish you could some home and kiss me yourself.” But this is only one in a thousand. But such is war and we are getting used to it and can look on scenes of war, carnage and suffering with but very little feeling and without a shudder.

July 4. This day reminds us of our independence and what it cost to achieve it and what it is now costing to maintain it. The rebels during the night have retreated for sure, and we have gained a glorious victory and we feel elated and joyous, and start in pursuit.

Chapman served for two more years before being discharged June 13, 1865.

Explore!

Read more stories from the 2003 Nov/Dec/Jan 2004 issue

Read more stories about Connecticut in the Civil War and Connecticut at War on our TOPICS pages