By Sarah P. Sportman and David E. Leslie

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Spring 2020

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

Archaeologists recently discovered the oldest known archaeological site in Connecticut. This 12,500-year-old Paleoindian site, the Brian D. Jones Site, is located five feet below a bank of the Farmington River in Avon.

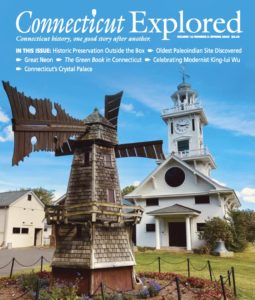

Paleoindians, the first inhabitants of North America, lived here at the end of the last ice age, approximately 10,000 to 13,000 years ago, when Connecticut was a cold, dry tundra. The Connecticut Department of Transportation (DOT) contracted Archaeological and Historical Services, Inc. (AHS) in 2019 to excavate the site in advance of construction of a new bridge over the river, as required by state and federal laws.

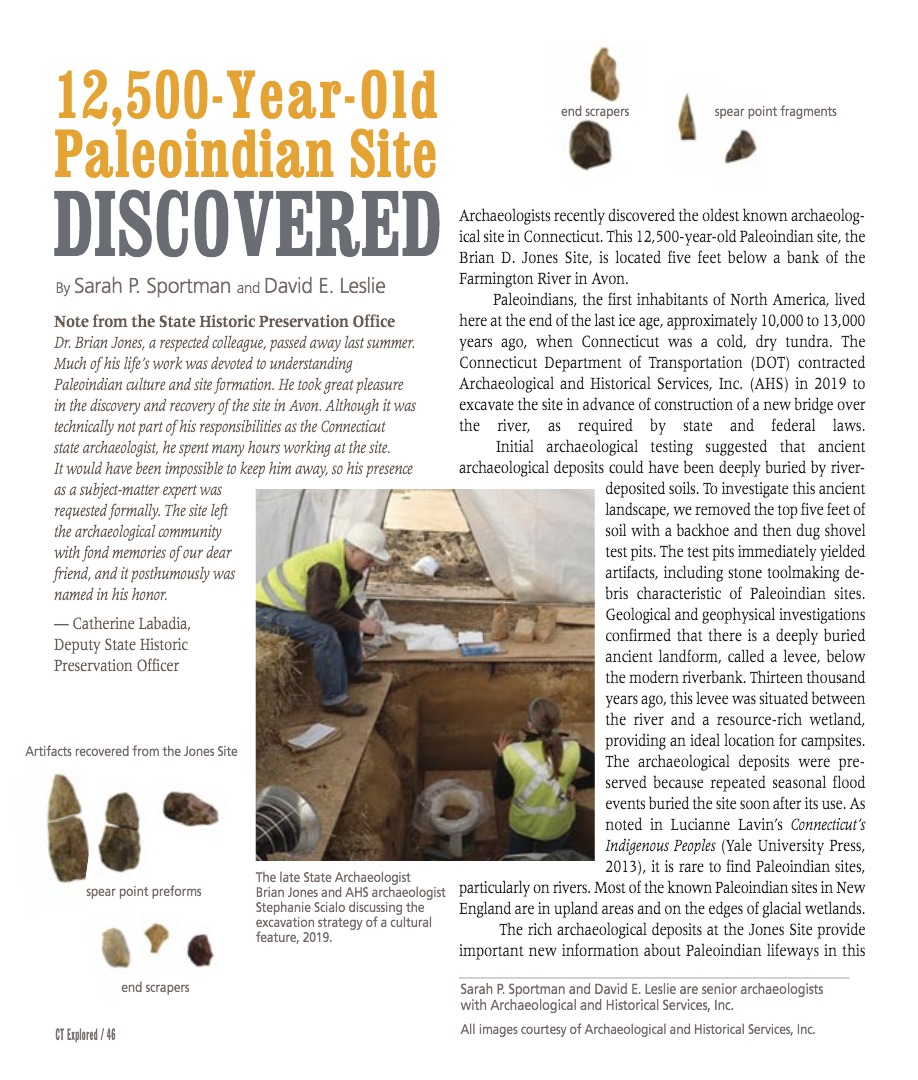

Initial archaeological testing suggested that ancient archaeological deposits could have been deeply buried by river-deposited soils. To investigate this ancient landscape, we removed the top five feet of soil with a backhoe and then dug shovel test pits. The test pits immediately yielded artifacts, including stone toolmaking debris characteristic of Paleoindian sites. Geological and geophysical investigations confirmed that there is a deeply buried ancient landform, called a levee, below the modern riverbank. Thirteen thousand years ago, this levee was situated between the river and a resource-rich wetland, providing an ideal location for campsites. The archaeological deposits were preserved because repeated seasonal flood events buried the site soon after its use. As noted in Lucianne Lavin’s Connecticut’s Indigenous Peoples (Yale University Press, 2013), it is rare to find Paleoindian sites, particularly on rivers. Most of the known Paleoindian sites in New England are in upland areas and on the edges of glacial wetlands.

The rich archaeological deposits at the Jones Site provide important new information about Paleoindian lifeways in this region. People repeatedly visited the site over hundreds of years to hunt and gather plant and animal foods, collect stone for toolmaking, and make and repair their toolkits. We found more than 100 stone tools, thousands of pieces of stone toolmaking debris, a drilled stone pendant fragment, and grinding stones for processing nuts, tubers, and possibly pigments such as ochre. We also found 27 cultural features: non-portable artifacts such as fire pits and the remains of wooden posts. Such features are incredibly rare on sites of this age; only a handful have been found in New England. Several of the fire pits contained the burned remains of cattail, pin cherry, strawberry, acorn, sumac, water lily, and dogwood, along with burned animal bones. Charcoal from one of the features was radiocarbon dated to between 12,568 and 12,410 years ago. The site is one of only a few well-dated Paleoindian sites and among the earliest sites in the Northeast. The distribution of artifacts, fire pits, and posts across the site is suggestive of several individual living spaces and activity areas.

The stone (lithic) artifacts from the Jones Site are made from a variety of materials found across the Northeast, including chert from the Hudson Valley of New York and northern Maine, jasper from eastern Pennsylvania, and rhyolite from northern New Hampshire. While Paleoindians seem to have preferred these high-quality exotic materials, people at the site also made tools out of local chalcedony, siltstone, and quartz. According to Jonathan Lothrop and his colleagues in “Early Human Settlement of Northeastern North America” (Paleoamerica, 2016), Paleoindian sites in the Northeast usually contain this wide range of materials, which archaeologists interpret as evidence of large territories and long-distance seasonal migration.

The Jones Site contained tools typically found at Paleoindian sites, including part of a fluted spear point. Only Paleoindians made fluted points, which are considered a diagnostic artifact of the period. No complete points were recovered, but numerous channel flakes, a byproduct of spear-point production, were found, so we know the points were made on site. While spear points clearly indicate hunting, the other tools such as scrapers, perforators, and grinding stones were used to butcher animals, grind plant foods, make wood and bone tools, and process animal skins for clothing and tents. The drilled stone pendant fragment and chunks of ochre provide the earliest known evidence in Connecticut for personal ornamentation and artistic expression.

The Jones Site contained tools typically found at Paleoindian sites, including part of a fluted spear point. Only Paleoindians made fluted points, which are considered a diagnostic artifact of the period. No complete points were recovered, but numerous channel flakes, a byproduct of spear-point production, were found, so we know the points were made on site. While spear points clearly indicate hunting, the other tools such as scrapers, perforators, and grinding stones were used to butcher animals, grind plant foods, make wood and bone tools, and process animal skins for clothing and tents. The drilled stone pendant fragment and chunks of ochre provide the earliest known evidence in Connecticut for personal ornamentation and artistic expression.

Due to the significance of the Jones Site, the DOT committed to 100 percent excavation of the site and is supporting a series of specialized scientific analyses to better understand Paleoindian lifeways and local environmental conditions in this period. DOT’s diligence facilitated the full investigation of the site while maintaining the bridge construction schedule. The Jones Site provides a key piece of the puzzle in the search for information about the lives of Connecticut’s first people.

Sarah P. Sportman and David E. Leslie are senior archaeologists with Archaeological and Historical Services, Inc.

In Memoriam

by Catherine Labadia, Deputy State Historic Preservation Officer

Dr. Brian Jones, a respected colleague, passed away last summer (2019). Much of his life’s work was devoted to understanding Paleoindian culture and site formation. He took great pleasure in the discovery and recovery of the site in Avon. Although technically not part of his responsibilities as the Connecticut state archaeologist, he spent many hours working at the site. It would have been impossible to keep him away, so his presence as a subject-matter expert was requested formally. The site left the archaeological community with fond memories of our dear friend, and it posthumously was named in his honor.

Explore these other Archaeology Stories!

“Underwater Archaeology: Finding Isabel,” Spring 2018

“Rediscovering Albert Afraid-Of-Hawk,” Summer 2014

“Waste Not, Want Not: What a Colonial Midden Can Tell Us,” Fall 2012

“Exploring and Uncovering the Pequot War,” Fall 2013

“Nick Bellantoni: Right Down the Street, and Right Beneath Your Feet,” Summer 2014