By Brian Jones and Kevin McBride

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Summer 2019

From the early 1600s through the mid-17th century, the region we know today as Connecticut was a hotly contested landscape where international economic power struggles unfolded—some influenced by local factors and others by international considerations. Three main actors were involved: the Native Americans, the Dutch, and the English. All had different but overlapping interests in the area that became Connecticut—and in its resources.

The original Native inhabitants found themselves fighting among themselves over control of new European resources, which ultimately could be used to expand their economic and political power. The Dutch focused on the trade of beaver pelts and wampum to strengthen their global economic position and legitimize control of New Netherland. The English had some interest in that trade, too, and in limiting Dutch sovereignty in the region, but they saw Connecticut primarily as a place where overcrowded Massachusetts Bay towns could vent their numbers during a mass migration from the English homeland.

The original Native inhabitants found themselves fighting among themselves over control of new European resources, which ultimately could be used to expand their economic and political power. The Dutch focused on the trade of beaver pelts and wampum to strengthen their global economic position and legitimize control of New Netherland. The English had some interest in that trade, too, and in limiting Dutch sovereignty in the region, but they saw Connecticut primarily as a place where overcrowded Massachusetts Bay towns could vent their numbers during a mass migration from the English homeland.

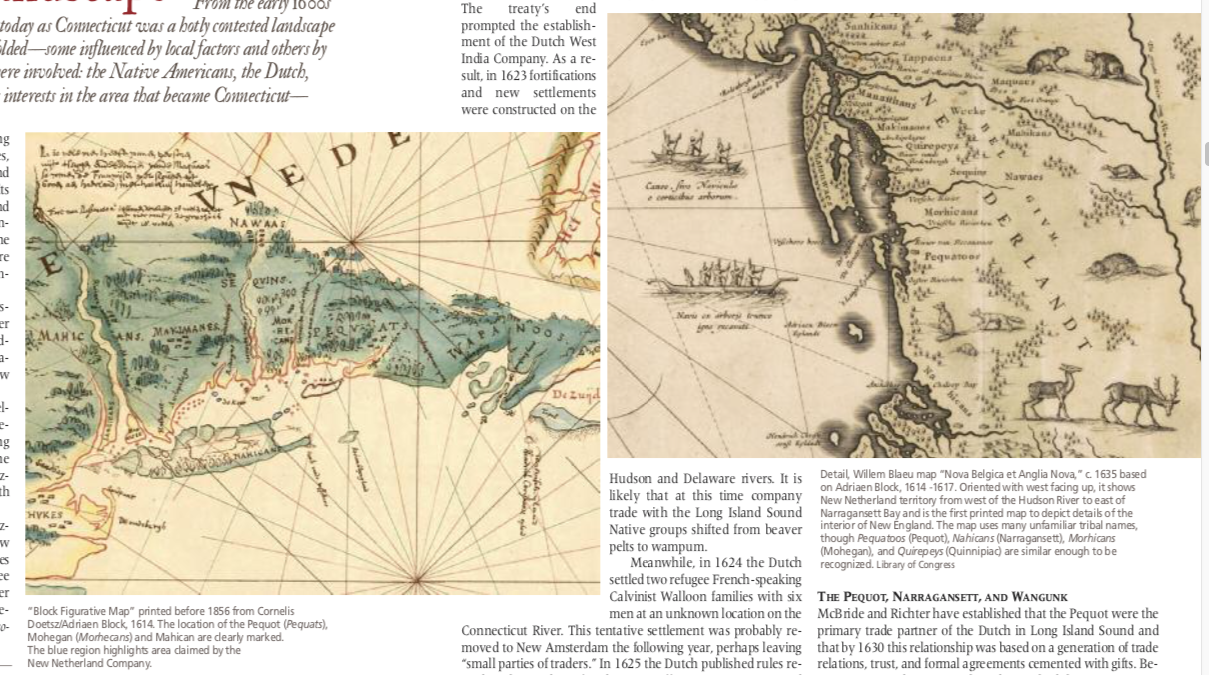

The Dutch initiated the first focused exploration of Long Island Sound and its rivers between 1611 and 1614, likely after Basque, Norman, and Dutch free traders and fishermen, according to James Bradley in “Before Albany: An Archaeology of Native-Dutch Relations in the Capital Region 1600-1664” (New York State Museum Bulletin, 2007).

The 1614 formation of the New Netherland Company developed from merchant and primary investor Lambert van Tweehuysen’s explorations. Three years of exploration and mapping by Adriaen Block and three other ships’ captains defined the New Netherland territory between the Delaware River and Buzzards Bay and initiated a period of regular trade contact with the Native Americans.

Fort Nassau was established at modern-day Albany, emphasizing the importance of this location to the beaver trade. The New Netherland Company’s monopoly on trade, provided by the States General of the Netherlands, expired in 1618, and Dutch free traders regained access to the region. An estimated 10,000 beaver pelts were taken annually from the Connecticut River Valley between 1614 and 1624, notes Daniel K. Richter in Before the Revolution: America’s Ancient Pasts (The Belknap Press, 2011).

In 1620 a group of Leiden-based English Puritans settled Plymouth Plantation just beyond New Netherland territorial claim. The Dutch likely saw this resource-starved group as a trade opportunity rather than a threat. This would soon change: 1621 marked the end of the 12-year-old Dutch peace treaty with Spain, after which Atlantic seagoing became increasingly risky. The treaty’s end prompted the establishment of the Dutch West India Company. As a result, in 1623 fortifications and new settlements were constructed on the Hudson and Delaware rivers. It is likely that at this time company trade with the Long Island Sound Native groups shifted from beaver pelts to wampum.

Meanwhile, in 1624 the Dutch settled two refugee French-speaking Calvinist Walloon families with six men at an unknown location on the Connecticut River. This tentative settlement was probably removed to New Amsterdam the following year, perhaps leaving “small parties of traders.” In 1625 the Dutch published rules regarding the conduct of traders in an effort to insure peace (and prosperity) with their important Native partners, according to Kevin McBride in his essay in the forthcoming Dutch and Indigenous Communities in 17th-Century Northeastern North America: What Archaeology, History, and Indigenous Oral Traditions Teach Us About Their Intercultural Relationships (SUNY Press). By 1627 the Dutch also provided most of the European goods used by the Plymouth colony to trade with their own Native allies, according to Richter.

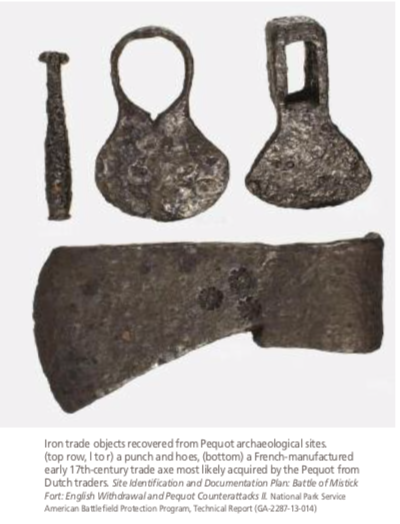

The Pequot, Narragansett, and Wangunk

McBride and Richter have established that the Pequot were the primary trade partner of the Dutch in Long Island Sound and that by 1630 this relationship was based on a generation of trade relations, trust, and formal agreements cemented with gifts. Between 1609 and 1630, Dutch trade enriched the Pequot in European material goods that the tribe in turn traded with Native peoples farther inland and used as raw materials for producing their own repurposed goods, such as brass arrow points and iron-bladed celts. Their economic enrichment placed the Pequot socially and militarily in a dominant position over neighboring tribes.

Meanwhile, the English at Plymouth had developed trade relations with the Narragansett. William Wood, writing from Plymouth in 1634, described the Narragansett as the “most rich also, and the most industrious, being the storehouse of all such wild merchandise as is amongst them.” He also describes the tribe as the “mintmasters” of wampompeag (wampum). He continues, “Since the English came, they have employed most of their time in catching of beavers, otters, and musquashes, which they bring down into the bay, returning back loaded with English commodities, of which they make a double profit by selling them to more remote Indians who are ignorant at what cheap rates they obtain them in comparison of what they make them pay, so making their neighbors’ ignorance their enrichment.”

This statement describes the mechanism through which the coastal wampum-producing tribes, through access to European goods, increased their own wealth and standing. It also suggests that the English appear to have initiated trade and diplomacy with the Narragansett by the early 1630s, threatening the Dutch monopoly on trade in the region. In 1636 the Dutch responded by establishing a trading post at Dutch Island in Narragansett Bay, underscoring the growing international competition over wampum and marking the beginnings of the political divisions between southern New England tribal communities that would soon have significant repercussions.

The Wangunk and related tribes occupied a number of villages in the central Connecticut River Valley between present-day Windsor Locks and East Haddam (referred to hereafter as River Tribes). In 1631 three wars between the Pequot and River Tribes resulted in Wangunk subjugation to the Pequot, as McBride and colleagues discuss in Site Identification and Documentation Plan:Battle of Mistick Fort: English Withdrawal and Pequot Counterattacks II (National Park Service American Battlefield Protection Program,Technical Report, 2017). This effectively allowed the Pequot to control trade on the Connecticut River with the Dutch and required the River Tribes to make tribute payments to the Pequot.

The 1631 expedition of the Connecticut River sachem Wahquimacut to the Plymouth and Massachusetts Bay plantations was a direct result of the Pequot- Wangunk wars. Wahquimacut entreated the English to settle among his people. This was clearly an effort to provide an English buffer to the belligerent Pequot and perhaps to free the River Tribes of their tribute obligations. Wahquimacut offered 80 beaver pelts per year to the English colonial leaders as an enticement to settle. Only Plymouth expressed interest. Massachusetts Bay considered the venture too risky, Henry R. Stiles suggests in his 1859 The History of Ancient Windsor, Connecticut.

The 1631 expedition of the Connecticut River sachem Wahquimacut to the Plymouth and Massachusetts Bay plantations was a direct result of the Pequot- Wangunk wars. Wahquimacut entreated the English to settle among his people. This was clearly an effort to provide an English buffer to the belligerent Pequot and perhaps to free the River Tribes of their tribute obligations. Wahquimacut offered 80 beaver pelts per year to the English colonial leaders as an enticement to settle. Only Plymouth expressed interest. Massachusetts Bay considered the venture too risky, Henry R. Stiles suggests in his 1859 The History of Ancient Windsor, Connecticut.

Governor Edward Winslow of Plymouth appears to have visited the River Tribes’ territory that year, as did John Oldham and others of the Massachusetts Bay settlements. Oldham was a Plymouth outcast and trader. His party received gifts of beaver and native hemp from Wahquimacut before returning home. It is likely that this initiated increased trade in the valley during the next two years, especially by Oldham and his men, but settlement would take longer.

King Charles of England signed a maritime treaty with Spain in 1632, effectively ending years of tacit English support of the Dutch Republic. Part of this political change appears to have stemmed from increased English interest in the Dutch claims in New Netherland. Probably in response, Dutch West India Company’s Governor Wouter van Twiller purchased land at Saybrook on which he erected the arms of the States General as a territorial marker for the English. This was followed in June 1633 by the Dutch West India Company’s purchase from the Pequot of a one-mile-by-one-third-mile tract of land at Hartford and his erection there of the House of Good Hope. In October the English provided Governor van Twiller with a document stating King Charles’s grant of Connecticut lands. The Dutch requested that the English refrain from settlement until the dispute over territorial claims could be resolved between the two countries.

The Plymouth Trading Company sent Captain William Holmes up the Connecticut River to establish a trading post of its own. Holmes’s bark sailed past the threats and cannon of the Dutch at Good Hope and rapidly constructed a palisaded trading house at Plymouth Meadow in present-day Windsor. Stiles wrote that Holmes had with him the Wangunk Sachem Attanwanott “and other Indian sachems” from whom he purchased the land. The Dutch sent a formal letter of complaint signed October 25, 1633. Holmes refused to respond, resulting in the arrival of a force of 70 Dutch soldiers in December. After a brief parley, the Dutch left the English in peace. That winter another Plymouth trader, Jonathan Brewster, reported from the trading post that many local Indians were dying. This probable smallpox outbreak, Andrew Lipman asserts in The Saltwater Frontier: Indians and the Contest for the American Coast(Yale University Press, 2015), led to a significant reduction in the Native population in the Connecticut River Valley and encouraged subsequent English settlement.

McBride suggests that the Dutch soldiers who arrived at Windsor may have been mobilized shortly afterward during a poorly documented Dutch-Pequot War in 1634. These Dutch hostilities may be related to a Pequot attack against other (possibly Narragansett) Indians who had come to trade with them. There is evidence that the Dutch allied with the Narragansett in this campaign against the Pequot. The Dutch retaliation resulted in the death of captive Pequot Sachem Tatobem, despite the Pequot’s payment of a high ransom in wampum. The Pequot appear to have retaliated by killing Captain John Stone and his crew of eight on the Connecticut River. Stone was an English trader, outlaw, and miscreant but also a friend of the Dutch governor. Afterward the Pequot approached Governor Winthrop in Massachusetts Bay for aid and opportunities for trade. McBride notes contradictory details regarding the exact sequence of the above events, but the result was a Dutch-Pequot War that left the political economy of Connecticut in turmoil. The death of Stone would eventually play an important role in the justification of the English-Pequot War three years later.

The Settlement of Wethersfield and the Pequot War

On May 6, 1635 the Massachusetts Bay Court passed an order allowing “the inhabitants of Watertown to remove themselves to anyplace they shall think meet to make choice, provided they continue still under this government.” Most historians agree, however, that about 10 adventurers from Watertown and their families did not wait for approval but settled Wethersfield in August 1634. They were followed by about 32 additional heads of households from Watertown in 1635. Shortly thereafter additional settlements were established at Windsor and Hartford.

At settlement, the area of Wethersfield was known as Pyquaug, perhaps meaning cleared or open lands, Sherman W. Adams and Henry Stiles suggest in The History of Ancient Wethersfield, Volume 1 – History (1904). It would be called Watertown and finally Wethersfield. The land was purchased by the plantations’ proprietors directly from Sowheage, a sachem of the River Tribes. The tract was six miles north-south along the river and extended five miles to the west and three miles on the eastern side. As part of this agreement, Sowheage and, though not recorded, presumably his tribe were permitted to live among the English for protection. For reasons lost to history, the proprietors did not keep their end of this bargain and, under pressure, Sowheage moved to Mattebasset (now Middletown). His anger over this is generally understood to have led him to encourage the Pequot attack against Wethersfield on April 23, 1637.

Relations between the English and Pequot had been deteriorating. Oldham, who had visited Wahquimacut in 1631 and was one of Wethersfield’s principal settlers, was killed in his trading vessel off Block Island on July 20, 1636, probably by the Manisses tribe. A month laterMassachusetts Bay launched a retaliatory expedition of 90 soldiers under John Endicott and John Underhill against the Manisses, Lipman chronicles. Associated English raids, justified by the earlier murder of Captain Stone, on a nearby Pequot village resulted in reprisal attacks against the English fort at Saybrook from the fall of 1636 through spring of 1637. These attacks and ambushes resulted in a number of English deaths and curtailed traffic on the Connecticut River, cutting off the young settlements at Wethersfield, Hartford, and Windsor.

Relations between the English and Pequot had been deteriorating. Oldham, who had visited Wahquimacut in 1631 and was one of Wethersfield’s principal settlers, was killed in his trading vessel off Block Island on July 20, 1636, probably by the Manisses tribe. A month laterMassachusetts Bay launched a retaliatory expedition of 90 soldiers under John Endicott and John Underhill against the Manisses, Lipman chronicles. Associated English raids, justified by the earlier murder of Captain Stone, on a nearby Pequot village resulted in reprisal attacks against the English fort at Saybrook from the fall of 1636 through spring of 1637. These attacks and ambushes resulted in a number of English deaths and curtailed traffic on the Connecticut River, cutting off the young settlements at Wethersfield, Hartford, and Windsor.

On April 23, 1637 a large Pequot force attacked English settlers working their fields at Wethersfield. Though accounts vary, the Pequot likely killed six men and three women and captured two girls, according to Adams and Stiles. The girls were eventually rescued by the Dutch, highlighting the complex political environment of the times. The raid on Wethersfield led to the May 1, 1637 declaration of war against the Pequot. On May 26 the English, with Mohegan and Narragansett allies, attacked Mistick Fort; that attack was followed by the destruction of other Pequot villages and the capture of Pequot prisoners and their subsequent sale into slavery. (For more about the Pequot War, see “Exploring and Uncovering the Pequot War,” Fall 2013 and available online.)

The war ended with the Treaty of Hartford on September 21, which stipulated that any surviving Pequot were to be dispersed among the Mohegan and Narragansett and were no longer to be called Pequot or to occupy their former territories. These harsh conditions were later mitigated with the establishment of a Pequot reservation in Noank in 1651 and another at Mashantucket in 1666. While the Pequot War terrified the English settlers between 1635 and 1637, its end established increased political and economic stability in the region. It also effectively undermined the Dutch West India Company’s territorial claims and trading monopoly in Connecticut.

Aftermath

The Pequot War did not mark the end of international and Native contests over territory in Connecticut. While the 1650 Treaty of Hartford officially reestablished the Dutch-English border 50 miles west of the mouth of the Connecticut River, the Dutch stubbornly held onto their sliver of eastern New Netherland territory, maintaining the Fort of Good Hope in Hartford. The fort finally fell without a fight to none other than Underhill in 1653 during the First Anglo-Dutch War, according to William DeLoss Love in his 1914 The Colonial History of Hartford: Gathered from the Original Records. The war was ultimately rooted in the increased strength of the English naval and commercial fleet under Oliver Cromwell and the passage of the 1651 Navigation Acts forbidding Dutch middlemen to sell wares in England. Tensions in the colonies would continue, with the critical loss of New Netherland to the English in 1664.

Despite some small-scale threats of conflict with Connecticut’s Native people, and certainly a continued degree of fear and distrust, the Connecticut Colony did not suffer significant Native assaults. This was in part a result of the strong alliance between the Connecticut Colony leaders and their Mohegan and Pequot neighbors. The losses in Connecticut in the 1675 King Philip’s War paled beside those experienced by the Massachusetts Bay Colony. With the close of that war, Native communities were gradually stripped of their remaining claims to Connecticut territory and were increasingly confined to reservations, forced to take refuge in the northwest hills or do their best to survive at the margins of English society. Never again would a dominant Native economic and military power like that of the Pequot have an opportunity to arise. English towns mushroomed and multiplied, and any lingering international and tribal territorial claims were soon drowned by the relentless tide of the growing Anglo population.

Brian Jones was the Connecticut state archaeologist. Kevin McBride is an associate professor in the anthropology department at University of Connecticut, Storrs. McBride last wrote “Exploring and Uncovering the Pequot War,” Fall 2013.