By Sandra P. Ulbrich

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Spring 2019

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

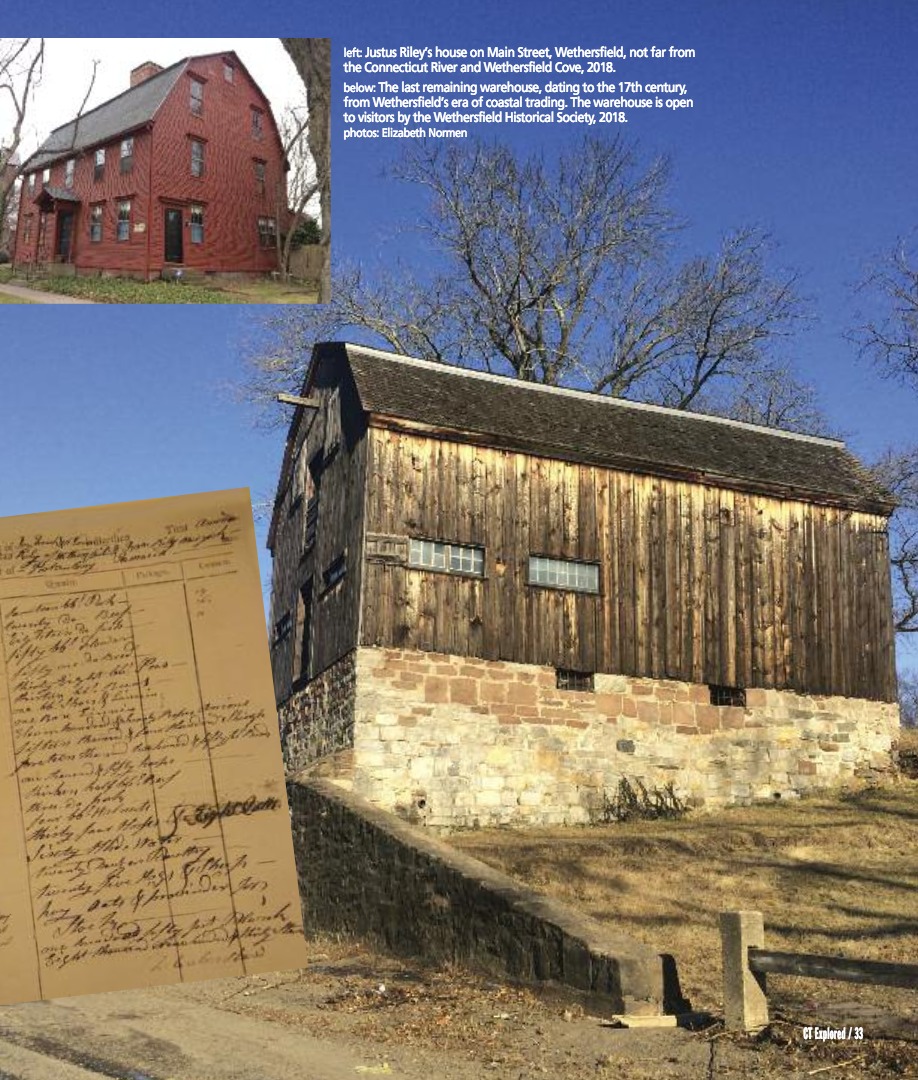

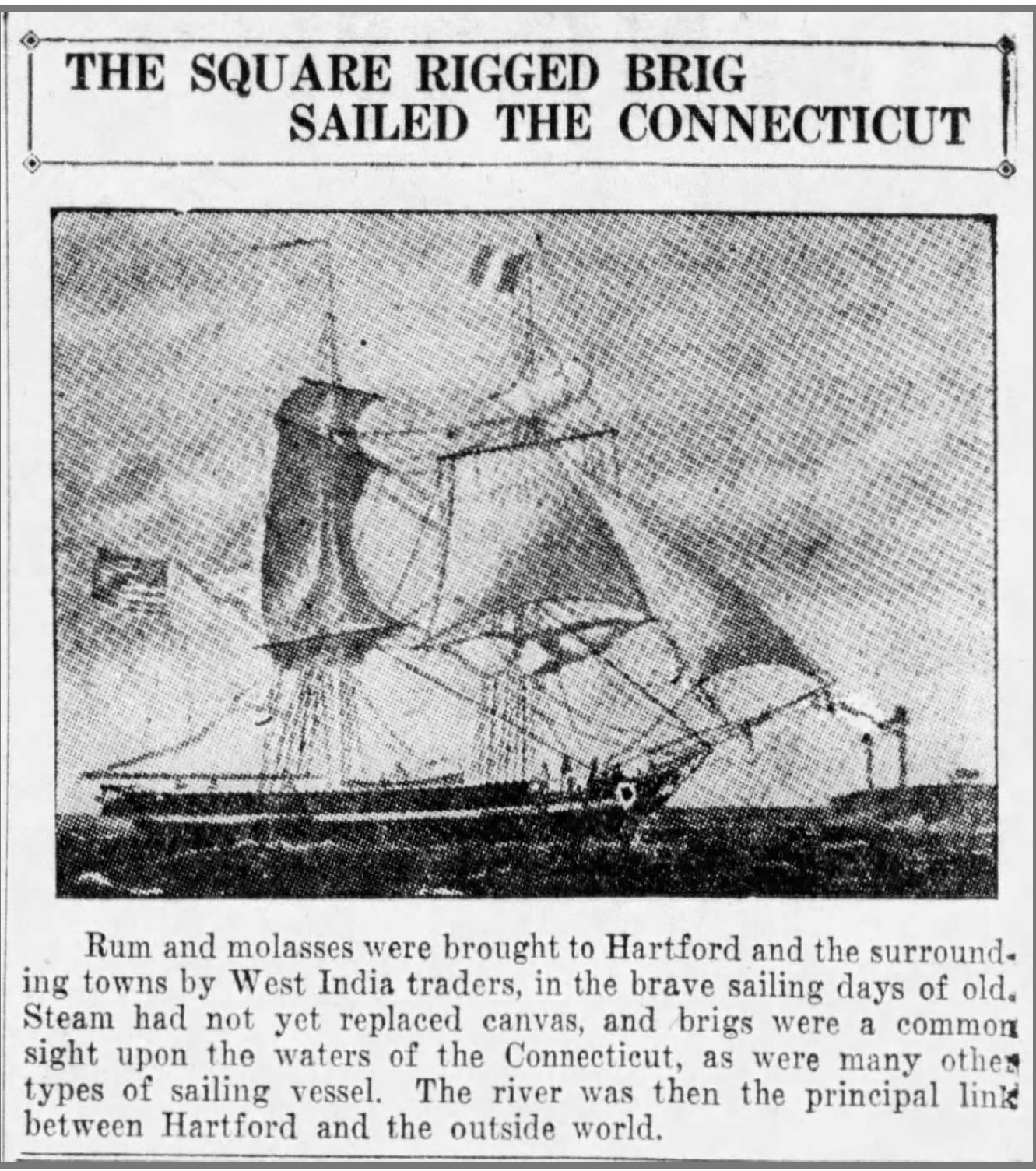

The Connecticut River brigantine Patty sailed right into a war in 1796, protected only by an American neutral policy. Her owner, Justus Riley of Wethersfield, expected his New England exports to make a tidy profit by capitalizing on the latest war between England and France, declared in 1793. Both adversaries needed supplies, and he was only too happy to satisfy their needs. Yet the outcome of the Patty voyage was quite different from the one he anticipated. Instead of collecting Caribbean imports at a Connecticut wharf, he found himself stuck in an interminable quagmire of international diplomacy, untried federal law, disruption of wars, congressional impasses, and presidential vetoes.

The New London customhouse cleared the Rocky Hill-built Patty for departure on July 31,1796, according to the Norwich Packet. Her figurehead pointed her 75-feet-2-inches-long hull out of the mouth of the Thames River into Long Island Sound and out to the Atlantic Ocean. Once upon her southerly course, she bore down with a swiftness that belied her carrying weight of 146 tons. The square-tucked sails of her twin masts drew full, shielding sheep, hogs, cattle, and horses on her deck. In her hold were oak-stave barrels stuffed with New England goods.

Riley would have preferred to sell the Patty or rent her out. In May 1796 his son Ezekiel, acting as his New York agent, advertised the two-year-old Patty for “sale, freight, or charter” in the New York Daily Advertiser at Lupton’s Wharf in Manhattan. No interested party came forward, so she returned to Connecticut and Riley prepared to send her out, largely with his own cargo. A July clearance at Middletown’s port and the collection of 19 shipping horses, recently shod at a New London blacksmith, signaled that she would sail once again. Captain Josiah Hempsted of Hartford, a nephew of Riley’s through marriage, contracted with Riley to sail her to the Swedish island of St. Bartholomew’s in the Caribbean. He stood to reap a profit of $1,567.60 from the sale of a portion of her exports, while Riley claimed the remaining exports, valued at $7,250.75, according to estate records for both men now held at the Connecticut State Library.

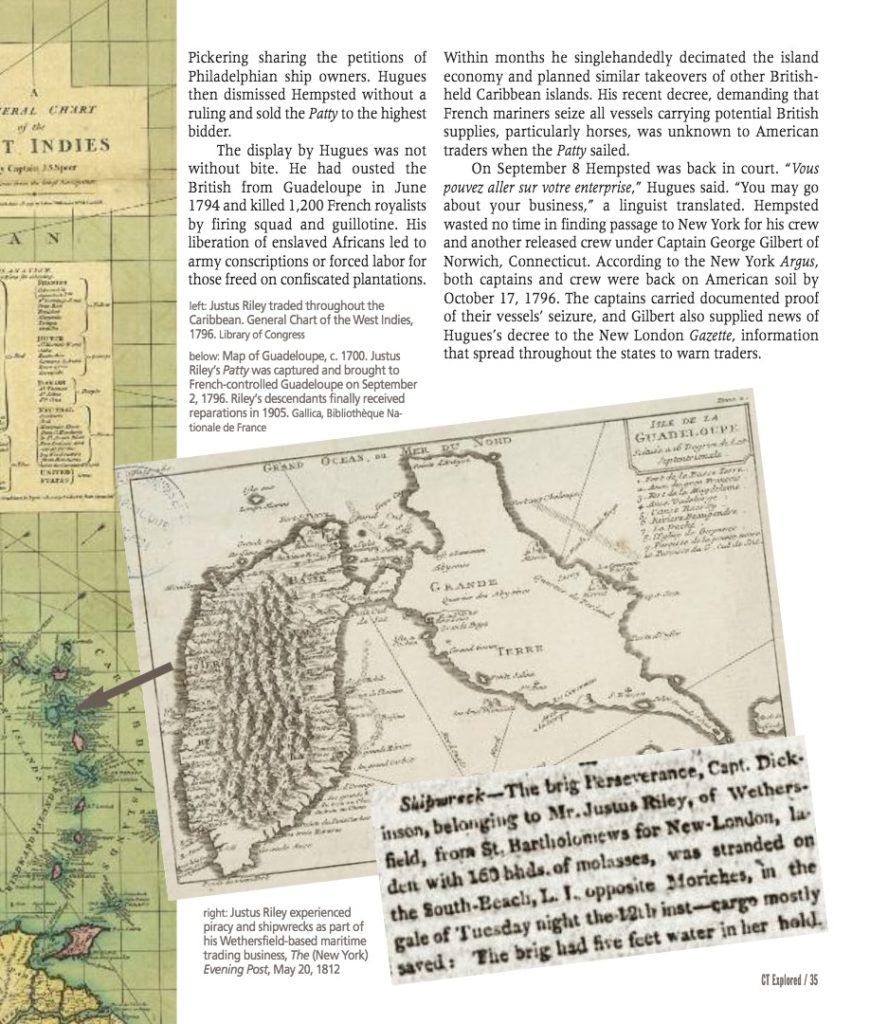

Hempsted skirted the Patty around Antigua’s coral reefs on her approach to St. Bartholomew’s, where he planned to sell all of the horses for a total of about $1,000 to eager buyers. Both British and French traders might vie for his cargo, since St. Bartholomew’s main port at Gustavia was an “emporium” of clandestine trade, according to the October 12, 1795 edition of Charleston’s City Gazette. However, on September 2, 1796, the French crushed those plans. At latitude 17 degrees and 24 minutes north of the equator, the Iris, a well-armed French cruiser, pounced on the defenselessPattyand commandeered her to Guadeloupe.

Unlike during the peaceful maiden voyage of the Patty to then-British-controlled Guadeloupe, her sailors now feared for their lives in the deplorable conditions surrounding confinement to a French prison jail cell. A guard marched Hempsted past a guillotine in Basseterre Square on September 3 and to the makeshift courtroom of the Tribunal de Commerce et des Prises. The presiding magistrate was Commissioner Victor Hugues, the Robespierre of the West Indies and a Jacobin appointee of the First French Republic. Hugues railed his clenched fists close to the face of Hempsted and spewed vicious words against Americans and their government for their abandonment of treaty obligations. “I have confiscated your vessel and cargo, you damned rascal,” a linguist translated. The account was later included in a February 27, 1797 report by U.S. Secretary of State Timothy Pickering sharing the petitions of Philadelphian ship owners. Hugues then dismissed Hempsted without a ruling and sold the Patty to the highest bidder.

Unlike during the peaceful maiden voyage of the Patty to then-British-controlled Guadeloupe, her sailors now feared for their lives in the deplorable conditions surrounding confinement to a French prison jail cell. A guard marched Hempsted past a guillotine in Basseterre Square on September 3 and to the makeshift courtroom of the Tribunal de Commerce et des Prises. The presiding magistrate was Commissioner Victor Hugues, the Robespierre of the West Indies and a Jacobin appointee of the First French Republic. Hugues railed his clenched fists close to the face of Hempsted and spewed vicious words against Americans and their government for their abandonment of treaty obligations. “I have confiscated your vessel and cargo, you damned rascal,” a linguist translated. The account was later included in a February 27, 1797 report by U.S. Secretary of State Timothy Pickering sharing the petitions of Philadelphian ship owners. Hugues then dismissed Hempsted without a ruling and sold the Patty to the highest bidder.

The display by Hugues was not without bite. He had ousted the British from Guadeloupe in June 1794 and killed 1,200 French royalists by firing squad and guillotine. His liberation of enslaved Africans led to army conscriptions or forced labor for those freed on confiscated plantations. Within months he singlehandedly decimated the island economy and planned similar takeovers of other British-held Caribbean islands. His recent decree, demanding that French mariners seize all vessels carrying potential British supplies, particularly horses, was unknown to American traders when the Patty sailed.

On September 8 Hempsted was back in court. “Vous pouvez aller sur votre enterprise,” Hugues said. “You may go about your business,” a linguist translated. Hempsted wasted no time in finding passage to New York for his crew and another released crew under Captain George Gilbert of Norwich, Connecticut. According to the New York Argus, both captains and crew were back on American soil by October 17, 1796. The captains carried documented proof of their vessels’ seizure, and Gilbert also supplied news of Hugues’s decree to the New London Gazette, information that spread throughout the states to warn traders.

Hempsted had the unpleasant task of delivering the documentation of the Patty’s seizure to Riley, adding to Riley’s long list of losses. The British had robbed Riley of cargo of his sloop Dove in 1789, 1793, and 1794 and brigs Anne in 1793, Recovery in 1794, and Nabby in 1796. These vessels carried insurance, leaving the risks of their loss to insurance companies to shoulder, but high insurance rates due to increases of depredations led Riley to forgo insurance for the Patty.That regrettable decision now set him back $15,512.75, the cost of the ship and the cargo. Banking on a December 1793 promise by President George Washington that “measures would be taken to obtain redress…if documents be furnished,” Riley dispatched Hempsted to the federal capitol building in Philadelphia.

In the first-floor court chambers at Philadelphia’s City Hall on November 9, 1796, Hempsted gave sworn testimony about the Patty’s voyage for a formal deposition before Mayor Hilary Baker. The deposition passed to Secretary of State Timothy Pickering, who included it in his February 27, 1797 report about Philadelphian ship owners imploring government action to stop maritime depredations. In May 1797 the 4th Congressional Executive Papers show President John Adams to be sympathetic when he promised to seek “equal measures of justice from France” to counter the shipping attacks. Congress, though, was slow to back the president’s words. A year passed before Congress suspended trade with France, funded the completion of 10 federal ships to protect Americans traders, nullified American-French treaties, and authorized letters of marques and reprisals to merchants desiring to arm their vessels. Congress also ignored the issue of financial redresses sought by ship owners.

Meanwhile, Riley pressed on. He continued to send his ships out but shied from adding armament to his vessels. During the American Revolutionary War, his privateers had captured several British supply boats near Connecticut’s coast, but confronting well-armed enemy ships in distant waters presented too great a risk. Instead he instructed his captains to seek protective convoys made up of traders and federal ships. The intermittent convoys and scattered communication for safe passages, however, brought him more heavy losses at the hands of both the French and the British. Three-quarters of his fleet, numbering as many as 15 vessels during this period, saw French and British raids of their cargo. By 1806 French captures had reduced the fleet by around 40 percent.

The 1795 Anglo-American Treaty of Amity, Navigation and Commerce slowed British depredations and offered reparations. In his journals, now held at New York Historical Society, Ambassador Rufus King included three Riley vessels in his spoliation list and marked their reparations paid by England. At the same time France escalated hostilities against American vessels in retaliation for American negotiations with England, confiscating at least 2,700 vessels, according to naval historian John R. Spears in his 1901 article “Piracies Incident to the French Revolution.”

Diplomacy with France failed, but President John Adams refrained from declaring war and dispatched federal ships to pound French privateers in the Caribbean, a posture known as the Quasi-French War. Captain Moses Tryon of Wethersfield, a former master of two Riley privateers, aided in this mission with great aplomb as the commander of the U.S.S. Connecticut, activity chronicled in his ship log for the United States Navy.

The success of federal ships and the departure of Hugues from Guadeloupe accelerated a new treaty with France. The Louisiana Purchase Treaty of 1803 included the acquisition of the Louisiana territory and “indemnities mutually due” from spoliations prior to September 30, 1800. In his haste to seal the $15,000,000 acquisition; however, President Thomas Jefferson dropped the merchant’s reparations claim of $3,750,000. This oversight sparked an uproar among merchants who demanded redress, citing the Fifth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which stated “nor shall private property be taken for public use without just compensation.” Congress was forced to acknowledge the claims of incidents between 1793 and July 31, 1801, but refused financial responsibility for the spoliations. Merchants flooded congressional offices with petitions and documents. The Library of Congress stored many of these petitions, but its destruction by the British in 1814 obliterated those documents and extinguished hope for many petitioners.

The devastating effects of the Jefferson-imposed Embargo of 1807 and the War of 1812 further reduced trade. Riley’s fleet plunged from 20 vessels in 1796 to 3 by 1814. An increase to 6 vessels in 1815 showed a modest rebound for Riley, but another loss came when his brigantine Commerce, owned with business partners, was shipwrecked off of Africa in 1815. A fruitless suit against an insurance company for compensation of Commerce’s anticipated cargo of salt may have prompted Riley to renew his redress efforts in 1823 for his Pattyloss.

In mid-January 1824 Connecticut Senator James Lanman stood before the 18thU.S. Senate and read a petition, known as a memorial, for 84-year-old Justus Riley, seeking compensation for the loss of the Patty and her cargo. The memorial went to the Committee on Foreign Relations to “consider and report thereon.” Yet no resolution came for Riley, who died three weeks after the presentation of his memorial. His widow Mabel Buck Riley, his daughter Martha Riley (later Mrs. Chester Bulkley), and his son Justus Riley II submitted another memorial to the U.S. Congress in 1829. Hempsted heirs, too, entrusted their estate executor Daniel Buck to present their petition in 1830 following the death of Josiah Hempsted.

Martha Riley Bulkley, childless and the last surviving Riley petitioner, died in 1845. Her will errantly omitted much of the extensive property once owned by her father, and her prenuptial agreement with her husband Chester Bulkley opened the door for some crafty first cousins once removed. These children of her first cousin James Fortune had recently asserted their kinship ties to legally claim the potential Hempsted reparation award. Their court victory encouraged them to sue Chester Bulkley and claim the unnamed Riley property, including the possible Pattysettlement. Inexplicably, a Connecticut court ignored other closer cousins and ruled in their favor. On February 13, 1850, Connecticut Senator Truman Smith, a champion for French spoliation reparations, read a memorial to the 31stSenate for the Fortune cousins and filed it with the French Spoliations Committee. Two days later Congressman Thomas Belden Butler of Wethersfield read the same memorial before the U.S. House of Representatives and filed it with the Committee on Foreign Affairs, according to the Congressional Record. Congress brought no satisfaction to these Fortune petitioners, though.

Congressional records testify to the federal government’s inaction, pointing to its reluctance to part with U.S. Treasury funds. Throughout the 19thcentury, the U.S. Senate crafted further bills, but the house of representatives or the president’s veto stymied them. Nevertheless, both individual claimants and states often pressured Congress for reparation settlements. For instance, the State of Connecticut petitioned the 28th Congress three times between 1843 and 1844 for compensation concerning all state vessels mentioned in memorials. No resolution came by mid-century. The Fortune cousins waited for congressional action, but the Civil War interrupted all deliberation of their claims. After the war several senators renewed discussions to give “satisfaction and reprieve to merchants” in various bills. Yet the U.S. House thwarted bill passage due to partisan bickering and preoccupation with an economic depression, two federal scandals, and the Second Sioux War.

The mutual cancellation of claims owedby the United States and France in 1880 was the final catalyst for Congress to consider and finally pass an indemnity bill, spearheaded by Massachusetts Senator George Frisbee Hoar, on January 20, 1885. With the signature of President Chester A. Arthur, the new act allowed for approximately 5,000 claims to receive review by the U.S. Court of Claims. President Grover Cleveland vetoed a bill for funding, but Congress overrode it. Because the Deficiency Act of 1891 required incremental disbursements, subsequent omnibus acts set aside continued payment through the first quarter of the 20thcentury, with almost $5 million doled out for reparations, a quarter of the original estimate. Congressional journals show that the Patty claimwon approval on February 15, 1902, while only one other Riley vessel, the Geneva,gained approval in 1909 for a claim by heirs of insurance underwriters and heirs of Luther Savage, the last surviving business partner of Riley.

The mutual cancellation of claims owedby the United States and France in 1880 was the final catalyst for Congress to consider and finally pass an indemnity bill, spearheaded by Massachusetts Senator George Frisbee Hoar, on January 20, 1885. With the signature of President Chester A. Arthur, the new act allowed for approximately 5,000 claims to receive review by the U.S. Court of Claims. President Grover Cleveland vetoed a bill for funding, but Congress overrode it. Because the Deficiency Act of 1891 required incremental disbursements, subsequent omnibus acts set aside continued payment through the first quarter of the 20thcentury, with almost $5 million doled out for reparations, a quarter of the original estimate. Congressional journals show that the Patty claimwon approval on February 15, 1902, while only one other Riley vessel, the Geneva,gained approval in 1909 for a claim by heirs of insurance underwriters and heirs of Luther Savage, the last surviving business partner of Riley.

Riley Fortune Goodrich of Wethersfield, the son of the Fortune claimant Prudence Fortune Goodrich, had hired Attorney George G. Sill in 1885 to represent his generation of Fortune cousins, according to Connecticut State Library court records. He would have to wait 20 years before the 58th Congress forwarded the $15,512.74 payment to Sill, who remitted it to the Connecticut State Probate Court in Hartford. On May 2, 1905 Judge Harrison B. Freeman deducted court fees ($17.05) and probate taxes ($4,981.13) and awarded $5,265.81 to Goodrich and $2,932.90 each to siblings Gertrude and Edmund Fortune, the children of an original Fortune claimant, Justus Riley Fortune. The $1,567.50 Hempsted award found resolution on September 13, 1905. Judge Freeman signed the distribution for taxes and court fees ($26.27); Sill’s legal fees ($501.60) and $1,039.63 to 18 direct Hempsted heirs.

“Justice is the end of government,” wrote James Madison in the Federalist Papers. But expedient justice was left wanting. The quagmire of international diplomacy, untried federal law, interruptions of wars, congressional impasses, and presidential vetoes had stalled a resolution of the Patty claims for 109 years.This unsatisfying conclusion of a search for justice eluded the most deserving claimants, Justus Riley and Josiah Hempsted.

Sandra P. Ulbrich is an independent historian and lecturer. This article is part of a larger work-in-progress about Justus Riley (1739 – 1824).