(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Winter 2012/2013

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

“…let your Petitioners rejoice with your Honours, in the Participation, with your Honours, of that inestimable Blessing, Freedom”

In 1779, Prime and Prince, two men enslaved in Fairfield, petitioned the Connecticut General Assembly to end slavery in the state.

“Your Honours who are nobly contending, in the Cause of Liberty, whose Conduct excites the Admiration, and Reverence, of all the great Empires of the World, will not resent our thus freely animadverting, on this detestable Practice;. Altho our Skins are different in Colour, from those who we serve, yet Reason & Revelation join to declare, that we are the Creatures of that God who made of one Blood, and Kindred, all the Nations of the Earth; we perceive by our own Reflection, that we are endowed, with the same Faculties, with our Masters, and there is nothing, that leads us to a Belief, or Suspicion, that we are any more obliged to serve them, than they us […] we have Endeavoured rightly to understand, what is our Right, and what is our Duty, and can never be convinced, that we were made to be Slaves.”

Although the petition was denied, it stands as eloquent testimony to the tension between slavery and freedom in revolutionary Connecticut. In 1784, after rejecting other emancipation proposals, Connecticut lawmakers passed a law providing for the gradual end of slavery in the state. It did not free any living slaves but stated that children born into slavery after March 1 of that year would become free when they reached the age of 25 (later changed to 21). Connecticut would not fully abolish slavery until 1848, making it the last New England state to do so.

A hundred years after the Emancipation Proclamation was signed, Martin Luther King, Jr. stood before civil rights marchers at the Lincoln Memorial and invoked that document as both a “beacon of hope” and an unfulfilled promise. A year later, Robert Kennedy purchased one of the 48 copies signed by Lincoln to raise money for the war effort for his home, perhaps seeking inspiration as he worked on implementing the Civil Rights Act of 1963. In 2010, Barack Obama hung a copy of the Proclamation on a wall in the Oval Office, next to a bust of King. In 2011, the original was displayed for 36 hours at the Henry Ford Museum near Detroit. More than 21,000 people waited in line for hours (some overnight) to see it, and others had to be turned away.

The Emancipation Proclamation is revered in our time as a key document of American freedom. But it is also dismissed on the grounds that it did little to end slavery. The Proclamation was partial, affecting only areas then in rebellion against the Union, and narrowly written, justified in terms of military necessity rather than the ideal of freedom. It would take the 13th Amendment to truly abolish slavery in the United States, and—as King eloquently reminded his audience—it would be more than a 100 years before the Emancipation Proclamation’s promise of freedom would start to be fulfilled. Rather than hailing Lincoln as the “Great Emancipator,” historians in the past few decades have stressed the complexity of securing freedom, focusing especially on the actions of slaves who seized their own liberty by running to safety behind Union lines.

In reading the document, it’s easy to wonder whether Lincoln’s heart was really in it. Compared to Lincoln’s more quotable writings, author Lerone Bennett observed in Forced into Glory: Abraham Lincoln’s White Dream (2000), “There is no hallelujah in it. There is no new-birth-of-freedom swagger, no perish-from-the-earth pizzazz.” Its leaden, legalistic prose led historian Richard Hofstadter, writing in The American Political Tradition and the Men Who Made It (1948), to ridicule it as having “all the moral grandeur of a bill of lading.”

Perhaps the best contemporary assessment of the Proclamation was offered by Massachusetts Governor John Andrews, who called it “a poor document but a mighty act.” Indeed, the most recent scholarship—including Lou Masur’s Lincoln’s Hundred Days, Harold Holzer’s Emancipating Lincoln, and Alan Guelzo’s Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation—underscores the importance of Lincoln’s act as it explains why Lincoln shaped the document as he did. The Proclamation was the catalyst for, not the final chapter in, the ending of slavery. It immediately freed tens of thousands of slaves in Union-occupied areas and ensured that as Union forces took control of more territory, more widespread emancipation would follow. By committing the nation to ending slavery, it transformed the Civil War into a war for freedom, pushing the United States closer to its ideals of liberty and equality. By inviting African Americans to enlist in the military, it paved the way for their inclusion in the nation and the civil and voting rights that were granted under the 14th and 15th amendments.

When the Fairfield Museum and History Center set out to create an exhibition commemorating the 150th anniversary of the Emancipation Proclamation, we knew we wanted to help visitors connect to this landmark document from which we are distanced by time, language, and political context. We looked for different ways the exhibit could help people view the Proclamation through a contemporary lens, explaining the forces that shaped it and highlighting the ways it resonates today.

Broad parallels are not hard to find. Close examination of the evolution of the Emancipation Proclamation raises questions that are familiar to anyone who follows national politics today: When is the right time to act? How does a leader shape public opinion or respond to it? How does an outsider group become included in the nation? What are the limits of presidential authority during wartime? What course of action is clearly constitutional? How can ordinary people influence political decisions?

The Fairfield Museum’s exhibition Promise of Freedom, on view through February 24, 2013, explores these questions. To show how the Emancipation Proclamation fits into the broad sweep of America’s history, the exhibit begins with a focus on the ways in which, from the beginning, America’s promise of freedom, showcased in an early print of the Declaration of Independence, existed alongside the reality of slavery. Throughout his political career, Lincoln frequently invoked the Declaration, insisting that its promise of “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness” apply to all. The Declaration is accompanied by a copy of the U.S. Constitution that was printed in the Connecticut Courant during debates over its ratification in 1787; the paper matter-of-factly carried a runaway-slave advertisement alongside the nation’s founding document.

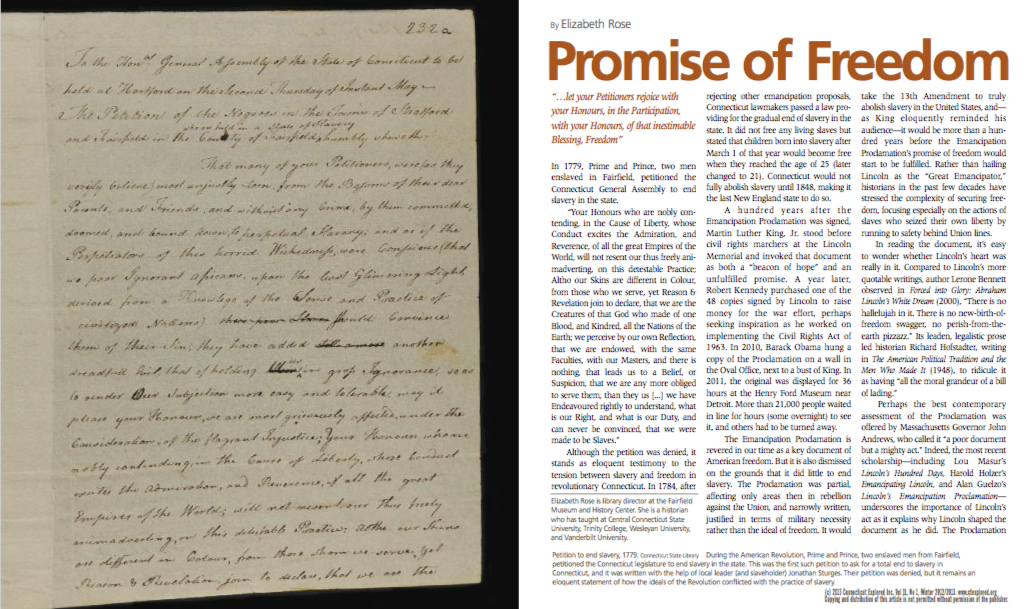

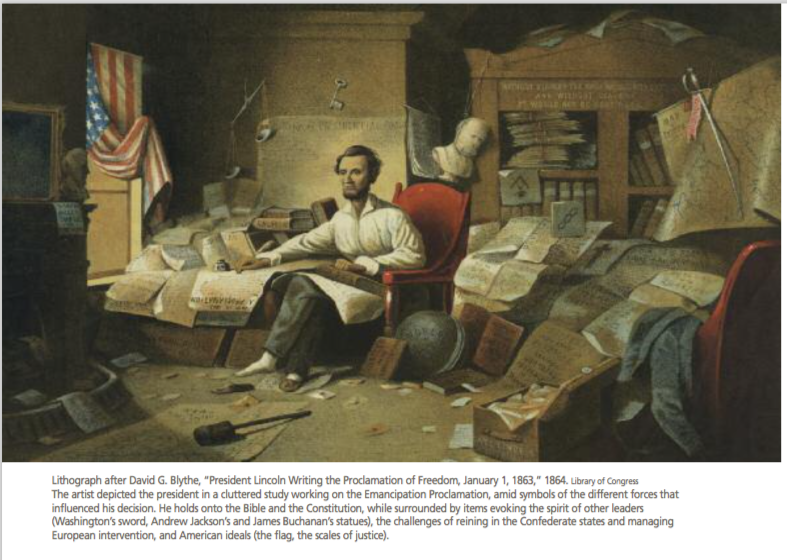

Like every important political issue in our democracy, the Emancipation Proclamation was deeply contested in its own time, drawing criticism from those who thought it did too little as well as from those who thought it did too much. To show how the Proclamation was regarded by different people in its own time, we have surrounded the copy we are displaying—one of a set that Lincoln signed in 1864 to raise money to aid Union soldiers—with images created by artists and political cartoonists at the time.

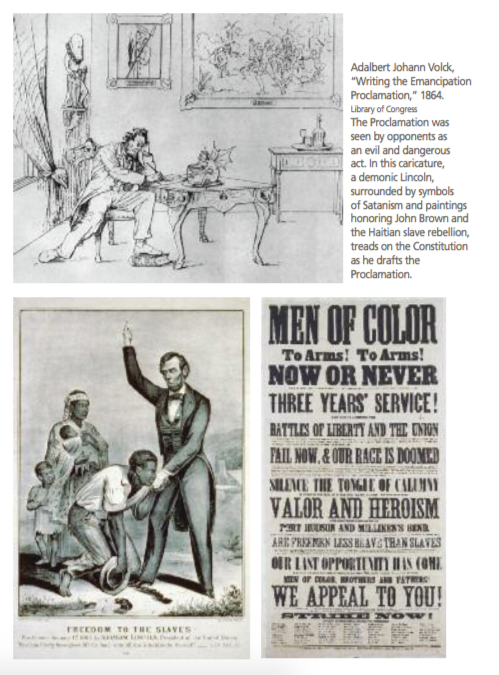

Lower left: Currier & Ives, c. 1865. Library of Congress Lower right: Broadside, 1863. The Library Company of Philadelphia

Most surprising to modern eyes are the negative depictions conveyed in these images: In one, Lincoln treads on the Constitution as he drafts the Proclamation, with a demon holding his inkwell. In another, he removes a mask to reveal a demonic face. The positive depictions show him as the “Great Emancipator” striking the chains off a kneeling slave or celebrate the moment of emancipation by contrasting the horrors of slavery with the benefits of freedom, which include schooling, wage-earning, and tranquil family life. Excerpts from newspaper editorials include some praising the Proclamation as “a second Declaration of Independence” and “a great moral landmark” and others condemning it as “grossly unconstitutional.”

One of the more jarring arguments against the Proclamation was that it would incite slave rebellions. One of the editorials warns that slaves would rise up and massacre whites “till their hands are smeared and their appetites glutted with blood.” Notably, General George B. McClellan opposed the idea of emancipation when Lincoln issued his preliminary proclamation in September 1862, saying he could not support “servile insurrection.” As it happened, it was whites who—during the worst rioting in American history—attacked and killed blacks in New York City’s 1863 Draft Riots. A letter from Fairfield resident Samuel Morehouse, who was teaching in New York City at the time, describes the violence and concludes, “I saw many things during Monday & Tuesday I hope never to see again.”

The exhibition also includes a brief explanation of what changed in the hundred days from the preliminary proclamation, issued on September 22, 1862, to the final one issued on January 1, 1863. Notably, the final proclamation dropped any mention of compensation to slave owners or of sending freed slaves to colonies in Africa or elsewhere. Both compensation and colonization had been part of Lincoln’s favored approach to emancipation. He had pushed the slaveholding border states to enact their own emancipation statutes featuring these provisions. In his message to Congress the month before the Proclamation, he proclaimed, “I cannot make it better known than it already is, that I strongly favor colonization.” In fact, the day before issuing the Proclamation, he signed an agreement to settle 5,000 blacks on an island off Haiti. But from January 1, 1863 onward, Lincoln would never again publicly advocate a policy of colonization; instead, he addressed the former slaves as potential wage earners and soldiers.

Indeed, the fact that the Proclamation invited freed slaves to become soldiers was almost as significant as emancipation itself, for serving in the military meant belonging to the nation. Lincoln became an avid proponent of black military service; by war’s end, about 180,000 African Americans had served, constituting nearly 10 percent of the Union force. Lincoln pointed to black military service when he refused to retract emancipation, saying the promise of freedom, “being made, must be kept.” To illustrate the importance of this development, the exhibit includes a rare tintype of an African-American soldier holding his gun, along with two striking recruitment posters proclaiming in bold letters, “Men of Color! To Arms! To Arms!” and “Freedom to the Slave.”

Promise of Freedom includes a rare copy, signed by Lincoln and congressional leaders in 1865, of the 13th Amendment as an important companion to the Proclamation. Lincoln, concerned that his Emancipation Proclamation could be overturned in court, had advocated behind the scenes for passage of the amendment, which was defeated in the House of Representatives in 1864 and finally passed in 1865. Lincoln, of course, he did not live to see it ratified, but he would have been gratified to know that it freed nearly a million slaves still held in bondage.

The freedom that the Proclamation helped bring about was incomplete, and the struggle for full liberty would continue for more than a hundred years. Promise of Freedom explores this phenomenon by displaying Thomas Nast cartoons critiquing Reconstruction politics, a Ku Klux Klan robe, and 1950s-era signs for segregated water fountains. An interactive area allows visitors to explore what freedom meant to former slaves in the 1860s and how aspects of freedom changed over time. Finally, an excerpt from Martin Luther King, Jr.’s speech during the 1963 March on Washington, with his call to fulfill the promise of freedom made a hundred years earlier, connects the modern civil rights movement with the Emancipation Proclamation.

Promise of Freedom includes an ancillary exhibition of iconic photographs from the civil rights movement of the 1960s. The work of documentary photographers Bruce Davidson, Bob Adelman, Gordon Parks, Ernest Withers, and others, on loan from the Howard Greenberg Gallery in New York City, includes images of everyday segregation and violence and of efforts to bring about change. These images underline the fact that the end of slavery was only the beginning of a very long quest for equality.

Although scholars, educators, and journalists have worked hard in recent years to uncover and share the history of Connecticut slavery, the popular perception of slavery as a Southern phenomenon remains. Promise of Freedom reminds visitors that slavery is part of Connecticut’s—and Fairfield’s—story as well.

Promise of Freedom features items connected to Fairfield history, such as the 1779 petition from Fairfield slaves excerpted above. Fairfield had one of the largest slave populations in Connecticut during the 18th century, and scattered throughout the Fairfield Museum’s archives are legal documents reflecting that slavery was a fact of life during this time. These include straightforward documents regarding the sale of slaves, including Amos, age 8, Gin, age 6, and Nell, age 12. It also includes Connecticut’s laws regulating slave behavior, along with documents shedding light on what it was like to live through Connecticut’s period of gradual emancipation. For instance, a slave named Jeffrey was born a few years too early to be affected by the gradual emancipation law. He was sold twice before finally being freed by his owner in 1812, at age 34.

Promise of Freedom explores the ways in which local residents were engaged with the struggles over slavery’s fate in the 19th century. Abolitionists in the area sometimes faced violent resistance, as when a mob blew up a church in the Georgetown section of Wilton after it hosted abolitionist speakers. Perhaps because of their history of slaveholding, Fairfielders were not prominent in the abolitionist movement in the state. Several Fairfield residents did play key roles in the Connecticut Colonization Society, whose goal of sending freed slaves to create colonies in Liberia and elsewhere was less controversial than outright abolition. Among those active in this effort was local judge Roger M. Sherman (nephew of Roger Sherman, Connecticut’s well-known signer of the Declaration of Independence). Sherman’s American Colonization Society certificate, signed by Secretary of State and Speaker of the House Henry Clay, demonstrates the wide appeal of this movement, which is rarely remembered today. Finally, the exhibition showcases a collection of artifacts showing ways in which people in the Fairfield region were touched by the Civil War, whatever their views on slavery.

Elizabeth Rose, Ph.D. is library director at the Fairfield Museum and History Center. She is a historian who has taught at Central Connecticut State University, Trinity College, Wesleyan University, and Vanderbilt University.

Explore!

Read more stories about the Emancipation Proclamation in the Winter 2012/2013 issue.

Read stories about the African American experience in Connecticut and the Civil War in Connecticut on our TOPICS pages.

Promise of Freedom: The Emancipation Proclamation was on view at the Fairfield Museum and History Center, 370 Beach Road, Fairfield through February 24, 2013. For more information visit fairfieldhistory.org.

Promise of Freedom was developed with guest curator Louis Masur of Rutgers University and assistance from Seth Kaller, Inc. and was made possible through the generous support of Connecticut Humanities, People’s United Bank, the Fairfield County Community Foundation, Newman’s Own, and Fairfield University.