Watercolor illustration

of the Foreign Mission School from Henry Martyn A’lan’s friendship album, 1824. Cornwall Historical Society

By Zachary Keith and Katherine Hermes

(c) Connecticut Explored, Inc. Winter 2016-2017

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

In 1824 Henry Martyn A’lan of Whampoa, China made a friendship album for Cherry Stone of Cornwall, Connecticut. A’lan, originally named Wu Lan, was a student, along with Cherokee and Choctaw people, Hawai’ians, and numerous people native to the Pacific Islands or North America at the Foreign Mission School in Cornwall. These young men, there to train as Protestant missionaries in order to evangelize their homelands, met young New England women and sometimes fell in love, an unintended consequence of geographic and cultural expansion.

Founded in 1817 by graduates of Williams College who had formed the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions in Boston in 1810, the Foreign Mission School was tucked away in the small town of Cornwall. The school garnered much public support for its mission to Christianize and educate foreign, “heathen” students. It thrived on donations, monetary and in kind, including the buildings and land for the school, according to John Demos in The Heathen School (Alfred A. Knopf, 2014).

The board was a product of a theological school, known as The New Divinity, populated by former students of theologian Jonathan Edwards. Timothy Dwight, president of Yale at the time of the Second Great Awakening and Edwards’s grandson, was instrumental in bringing students to the school. Religion was the core curriculum, and when students studied other subjects, they did so with biblically based texts.

Christian newspapers proudly reported the progress of the school. In October 1819, the Connecticut Journal announced that “four natives” would sail west to the Sandwich Islands (as Hawaii was then known) with several white missionaries to evangelize the people there.

Other than attendance at church services, or when the students were put to work in neighboring fields to support the operation of the school, students were not supposed to fraternize with locals. However, when student John Ridge became ill, he was cared for by the Northrup family. Ridge, the son of a prominent Cherokee family in Georgia, fell in love with Sarah Northup.

As James W. Parins relates in John Rollin Ridge: His Life and Work (University of Nebraska Press, 2004), neither the Northrups nor the Ridges were pleased. Ridge returned to Georgia, but their love persisted. Both families acquiesced and the couple married in 1824. School officials and town residents objected to the marriage, preferring instead marriages such as the one covered in the Haverhill (Massachusetts) Gazette between Thomas Hopoo, a graduate of the school, and Delia (last name unknown), a Christianized native of the Sandwich Islands.

One year later another student, John’s cousin Elias Boudinot, proposed to Harriet Gold. Several newspapers, including The Independent Chronicle and Boston Patriot, announced, “Another Marriage of an Indian with a White Girl Contemplated” and made clear their opposition. Reverend Lyman Beecher, a prominent evangelical minister, called the negotiations leading to the marriage “criminal.” The public backlash was swift and costly as Theresa Strouth Gaul, ed., notes in To Marry an Indian: The Marriage of Harriett Gold and Elias Boudinot in Letters, 1823-1839 (North Carolina Press, 2005). Donations dried up. Public support collapsed under the weight of two intermarriages between “heathen” students and local women. Boudinot and Gold married in 1826.

Ridge and Boudinot were perhaps the most famous graduates of the school for other reasons. Ridge used his education and standing in the Cherokee Nation to cultivate relationships with congressmen and President Andrew Jackson, after whom he named one of his sons. Boudinot became editor of the Cherokee Phoenix, a newspaper that was published in both Cherokee and English.

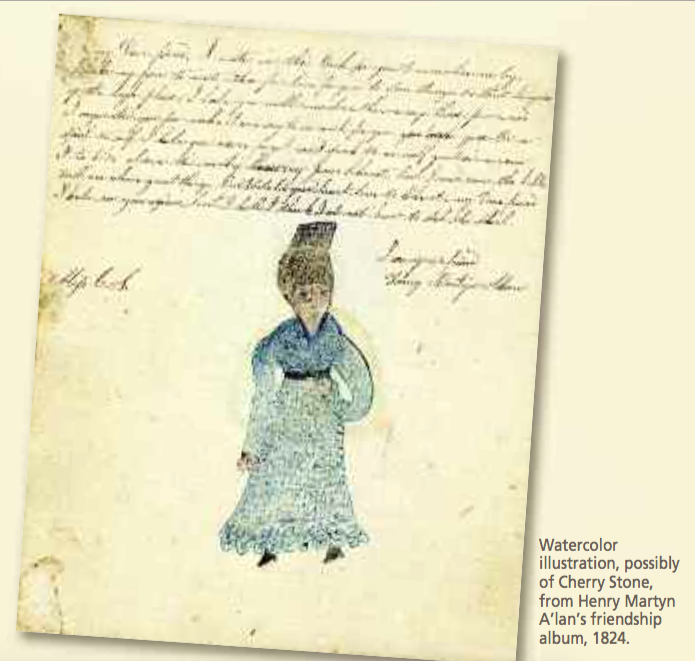

Watercolor illustration, possibly of Cherry Stone, from Henry Martyn A’lan’s friendship album, 1824. Cornwall Historical Society

Yet Ridge and Boudinot paid dearly for their education and familiarity with white society. As signatories of the Treaty of New Echota in 1835 that ceded Cherokee lands to the U.S. government and as advocates of Indian removal to Oklahoma, they became deeply unpopular. Their actions led to the long march known as the Trail of Tears, during which 4,000 Cherokee died.

Harriet died shortly after childbirth in 1836 and is buried in Georgia. Ridge and Boudinot took their families westward to Oklahoma but were assassinated there by fellow Cherokee in 1839. Sarah Northrup Ridge moved with her seven children to Arkansas.

The board closed the Cornwall school in 1826 following the scandals and decreases in funding. Their ambitious experiment affected the lives of 100 mostly indigenous pupils over the course of 10 years. Missionization, and particularly the foreign mission school movement, played a critical role in American westward expansion across the continent and beyond. The notion of manifest destiny embodied the values of cultural superiority and imperialism, but these couples were seen as undermining the process of assimilation.

Zachary Keith is pursuing a Masters in public history at Central Connecticut State University.

Zachary Keith is pursuing a Masters in public history at Central Connecticut State University.

Katherine Hermes is chair of the history department at Central Connecticut State University and has published works about Native Americans and the law in colonial New England.

Purchase the Issue