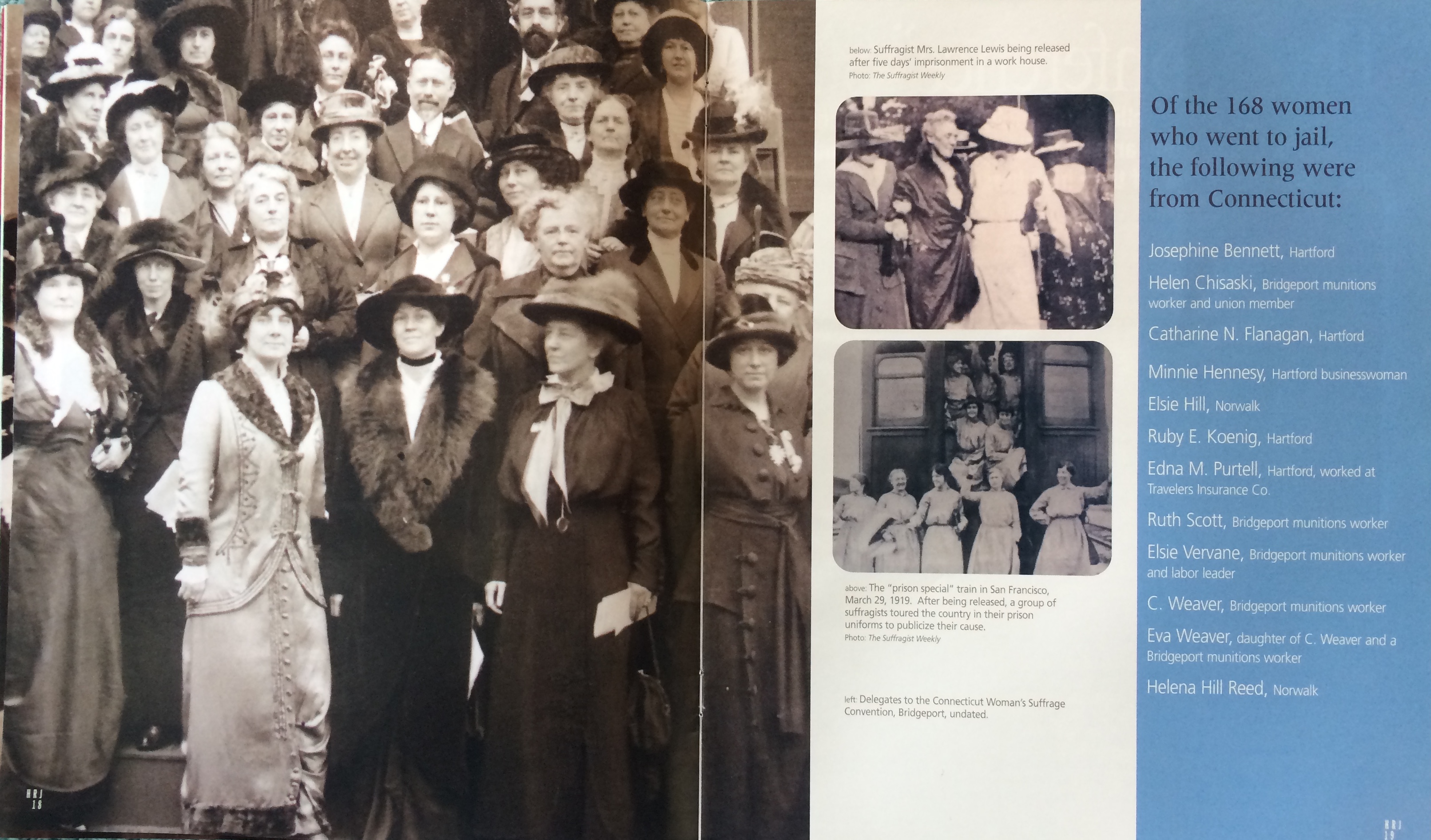

Josephine Bennett and daughters Frances and Katherine Bennett of Hartford, undated. State Archives, Connecticut State Library

By Mark Jones and Nancy O. Albert

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Fall 2005

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

All photographs from the Connecticut Women’s Suffrage Association, Connecticut State Library, State Archives, except where noted.

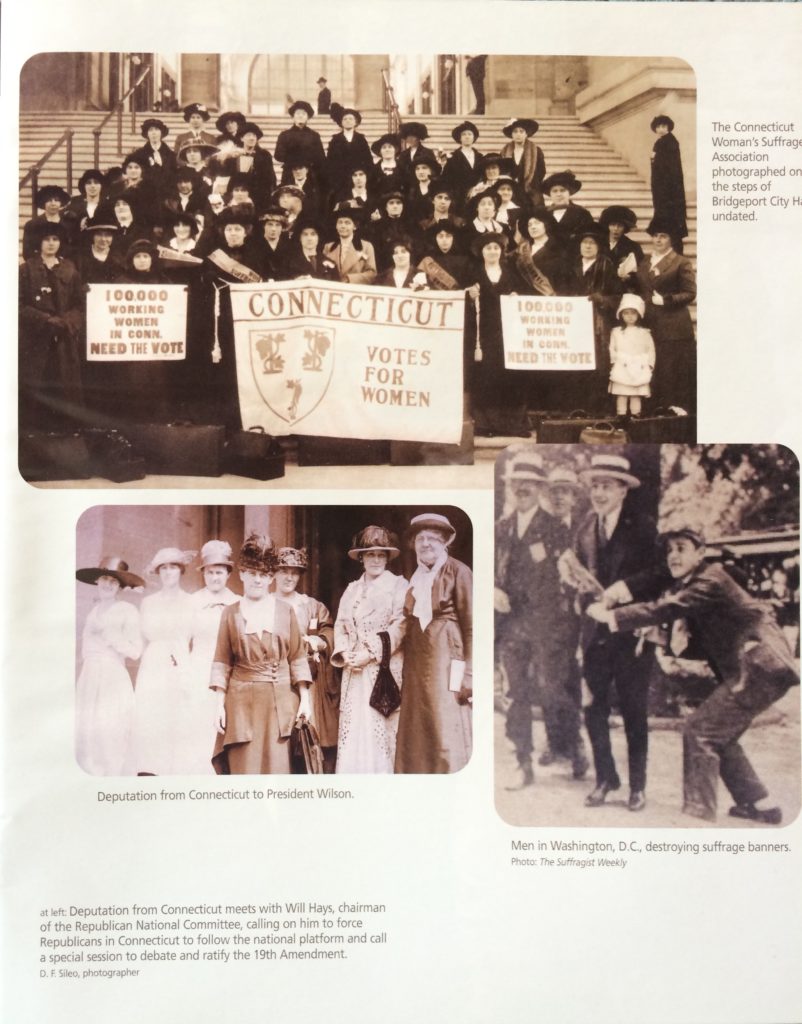

While World War I raged abroad, bitter battles were being waged here at home as women sought the right to vote. The National Woman’s Party (NWP) and National American Woman’s Suffrage Association were pursuing different tactics to accomplish the same end: passage of the 19th Amendment to the federal Constitution. The latter group hoped to achieve ratification by concentrating on a state-by-state strategy. The former chose non-violent civil disobedience in a highly visible location, the nation’s capital. Connecticut women played a leading role in this struggle.

Since 1917, under the leadership of founder and president Alice Paul, the NWP had staged daily demonstrations in front of the White House to focus national attention on what suffragists argued was the duplicity of President Woodrow Wilson. Wilson, they said, spoke of freedom and self-determination in the world yet took no action in the fight for the right of women to vote back home.

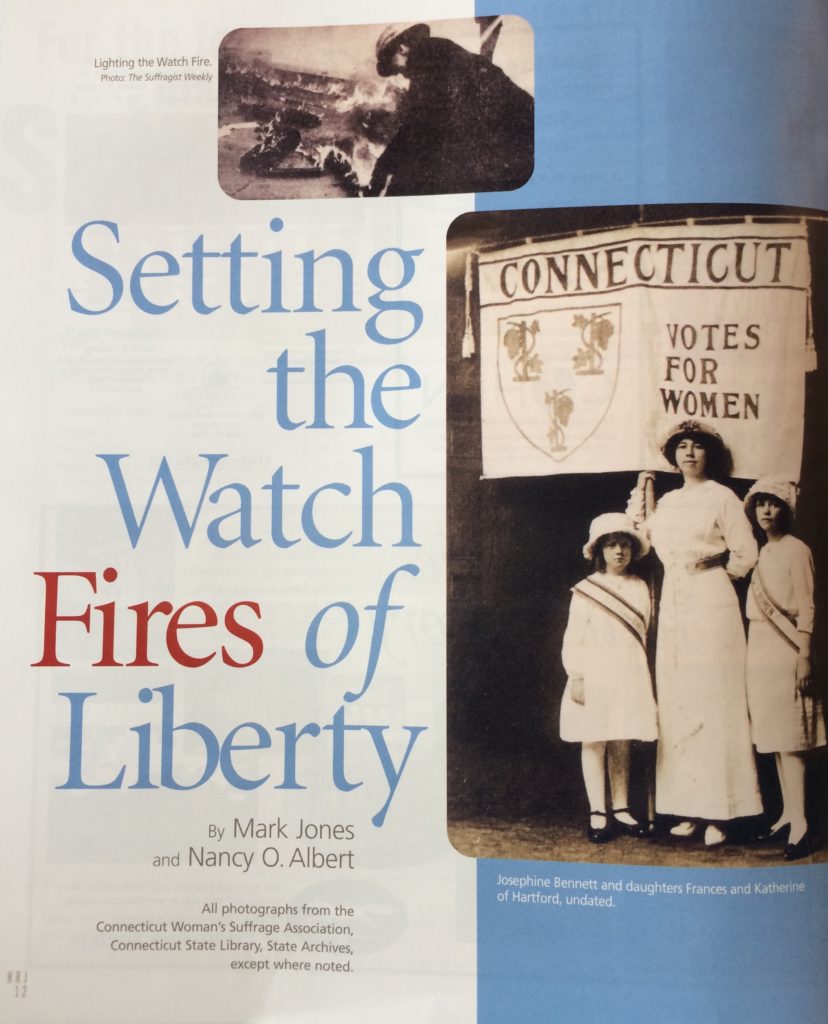

NWP volunteers marched every day from the party’s Washington, D.C. headquarters to the sidewalk in front of the White House carrying purple, white, and gold banners. Even after the nation’s entry into the European war in April, Alice Paul and her colleagues kept marching and picketing. Newspapers accused them of being unpatriotic. They braved angry crowds of men that pushed and shoved and ripped their banners while police stood by. Often the police themselves “roughed up” the women. Arrested on charges of obstructing traffic, the demonstrators could pay a fine or serve time in jail. One hundred sixty-eight heroines chose prison and many went on hunger strikes. Of these, 12 were from Connecticut.

Connecticut’s suffragists were led by ladies of wealth and standing, including Katharine Houghton Hepburn, Annie Poirritt, Frances Day and her daughter Josephine Bennett. Josephine Day married M. Toscan Bennett, son of a former insurance company president, corporate lawyer, and supporter of women’s suffrage and organized labor. Josephine Bennett served as treasurer for both the Connecticut Woman’s Suffrage Association and the Connecticut Woman’s Party; she also served on the NWP’s national advisory council. It was not usual for Bennett to drive Hepburn in her chauffeured automobile to country fairs in Connecticut, where the pair would campaign for women’s suffrage.

Though the organizations were largely led by upper-class women, munitions workers were brought to Washington to participate in the protest and were among the dozen state women arrested. In Connecticut, at least for a time, the suffrage movement crossed class lines and was a cause for all women. In addition to the suffrage, Bennett was active in founding the Hartford branch of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, assiting black leader Mary Townsend Seymour in forming a black female tobacco worker’s union [See “Audacious Alliances,” Sumer 2003], and opposing prostitution in the city.

Late in 1918, Bennett first participated in the Washington demonstrations. On December 26, she marched in the parade from the NWP headquarters to Lafayette Park across the street from the White House. Bennett was the first speaker, and she set the tone for what followed:

It is because we are moved by a passion for decency that we are here to protest the President’s forsaking the cause of freedom in America and appearing as a champion of freedom in the whole world. We burn with shame and indignation that President Wilson should appear before the representatives of nations who have enfranchised their women, as chief spokesman for the right of self-government while American women are denied that right. We are held up to ridicule to the whole word.

We consign to flames the words of the President which have inspired women of other nations to strive for their freedom while their author refuses to do what lies in his power to do to liberate women of his own country. Meekly to submit to this dishonor would be treason to mankind. Mr. President, the paper currency of liberty which you hand to women is worthless fuel until it is backed by the gold of action.

In January 1919, the NWP decided to start “Watch Fires of Liberty,” burning copies of Wilson’s speeches on the sidewalk in front of the White House as activists denounced the president’s words. Sometimes the police and other men scattered the few burning pieces of wood, and the female demonstrators would gather them back into a pile.

On “Connecticut Day,” January 8, 1919, Josephine Bennett and others started a Watch Fire with wood from Connecticut. Bennett addressed the crowd as she burned a speech President Wilson had given in Genoa, Italy as he laid a wreath at the foot of a statue of Christopher Columbus. She noted, as The Hartford Courant reported (January 9, 1919), “President Wilson said … that Columbus had discovered a land of freedom and that being free, America desired to secure freedom for other nations. Women resent the claim that America is free, while 20,000,000 of her citizens are still demanding enfranchisement.”

The police arrested Bennett and others and took them in police wagons to court, where they were tried and convicted of illegally starting a fire in front of the White House. The defendants were given a choice: pay a five-dollar fine or spend five days in jail. Bennett chose the latter. When she learned that 11 suffragist prisoners already in jail had begun a hunger strike, she joined them.

Bennett was unapologetic about the NWP’s tactics. “Belonging as I do to a disenfranchised class,” the told the court, “I hold that I have the right under the Constitution and Declaration of Independence to do anything necessary to remedy that condition. I consider the watch fires and the burning of President Wilson’s speeches on democracy a very mild form of protest which I shall continue to make.” Disenfranchisement was a greater “indignity” than jail. “If I am permitted visitors in jail,” the Courant reported her saying after her sentencing, “and they ask me why I am here, I shall say what Thoreau said: ‘Why remain on the outside when injustice is to be remedied,’”

Bennett was unapologetic about the NWP’s tactics. “Belonging as I do to a disenfranchised class,” the told the court, “I hold that I have the right under the Constitution and Declaration of Independence to do anything necessary to remedy that condition. I consider the watch fires and the burning of President Wilson’s speeches on democracy a very mild form of protest which I shall continue to make.” Disenfranchisement was a greater “indignity” than jail. “If I am permitted visitors in jail,” the Courant reported her saying after her sentencing, “and they ask me why I am here, I shall say what Thoreau said: ‘Why remain on the outside when injustice is to be remedied,’”

Back home, the Hartford Times was not sympathetic. It reported January 9, 1919:

Mrs. Toscan Bennett could probably burn and orate quite a lot around here without getting any of us very much disturbed or excited. … It is unfortunate that so many of the suffrage sisters have to make themselves ridiculous. Should many more of them go into it some of us will begin to feel there is some truth in the argument that women are mentally and temperamentally unfitted for the ballot.

On the other hand, a pro-suffrage newspaper, the Hartford Evening Post, defended the suffragists’ tactics (January 14, 1919):

The time may, and undoubtedly will come, when the next generation or the one after will marvel that there was any question … when it will seem impossible that women have had to submit to being thrown into vermin-ridden jails before they could convince the men.

One of Bennett’s jailhouse visitors was Connecticut’s U.S. Senator George McLean, a Republican who had voted against the 19th Amendment along with his Connecticut colleague, Republican Senator Frank Brandegee [See “Senator Brandegee Stonewalls Women’s Suffrage,” Spring 2016). Senator McLean emphatically told Bennett that she did not belong in jail and offered to pay her fine, but she refused. In fact, she blamed McLean for her jail sentence, claiming that if he had voted for the amendment, she would not have had to join her sisters in picketing the president.

On January 13, after Bennett and other suffragists were released, co-workers took them to the NWP headquarters in Washington for medical care, rest, and food. On Wednesday, Bennett arrived back in Hartford, where several suffragists greeted her. She was quoted in the Hartford Times (January 16, 1919) describing the conditions of the jail: “We of course refused to eat, but in any case the food was vile, and unfit for human consumption. The jail was unbelievable filthy. The rats used to run across my bed and roaches and bedbugs were plentiful.”

Connecticut women meet with Will Hays, chairman of the Republican National Committee, calling on him to force Republicans in Connecticut to follow the national platform and call a special session to debate and ratify the 19th Amendment. Photo: D. F. Sileo. State Archives, Connecticut State Library

In June 1919, the president and Democrats in Congress brought the amendment to a vote, in part because of pressure exerted by the NWP and activists like Josephine Bennett. In the summer of 1920, Tennessee passed the amendment and became the 36th state to do so—the last needed to ratify the amendment. On August 26, 1920, the 19th Amendment became law.

Mark Jones was Connecticut State Archivist, frequent contributor to CT Explored, and a member of its editorial team. Nancy O. Albert was CT Explored’s photo editor.

Read More!

Read all of our storied about Women’s Suffrage: 100th Anniversary of Women’s Suffrage