By Barbara Sicherman

Summer 2011 (c) Connecticut Explored

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

Harriet Beecher Stowe wrote Uncle Tom’s Cabin out of a burning need to “do something” about the infamous Fugitive Slave Law of 1850 that required Northerners to assist in returning enslaved men, women, and children to their owners. By any measure she succeeded. Published first as a magazine serial, Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1852) galvanized anti- slavery sentiment in the north and in England and became the best-selling book of the century after the Bible. Its success made Stowe the most powerful voice in the anti-slavery movement.

Writing was Stowe’s principal form of activism. Other Connecticut women before and since have found their own ways to obey the dictates of conscience. Here are the stories of six women who have been inducted into the Connecticut Women’s Hall of Fame and, like Stowe, made the most of the opportunities available in their time and place to further social justice.

Prudence Crandall (1803-1890) of Canterbury tried to advance the prospects of African-American girls by educating them, only to encounter intense hostility to blacks and those who sided with them.

Prudence Crandall

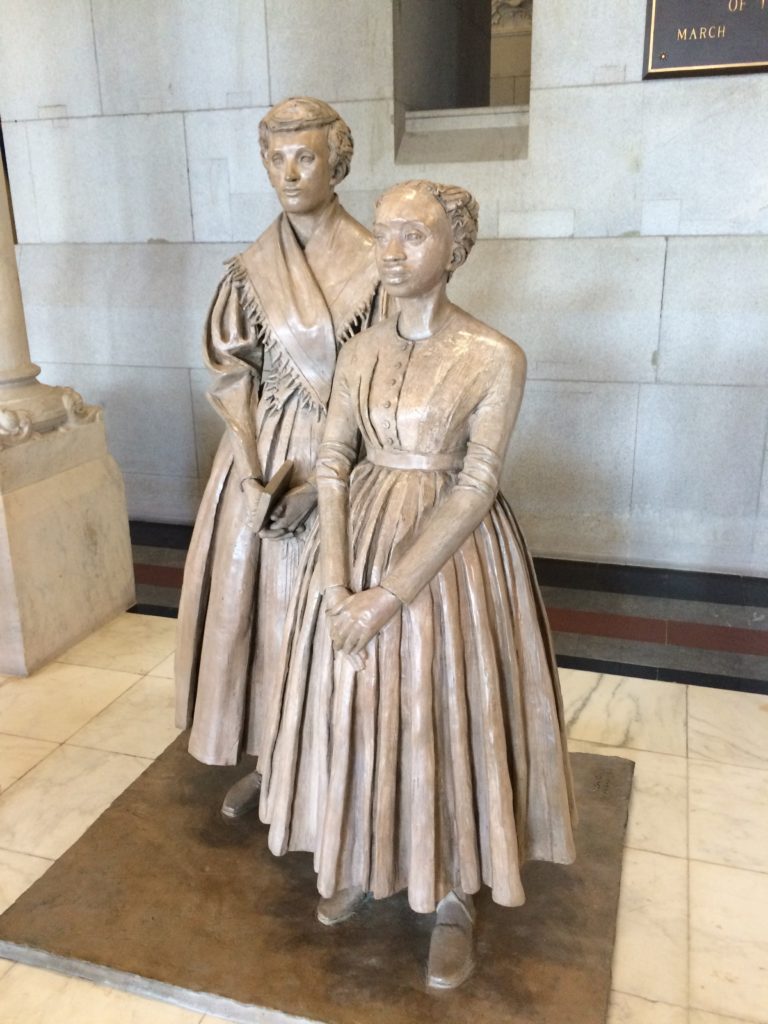

Prudence Crandall braved the wrath of the townspeople of Canterbury by taking a bold stand against racism in the early 1830s. Convinced that “the prejudice of whites against color was deep and inveterate,” as she wrote in an 1833 letter to the Windham County Advertiser, she admitted the daughter of a local African-American farmer to the Canterbury Female Seminary, which she had recently opened with the aid of the town’s leading citizens.

When parents objected, she approached William Lloyd Garrison and other abolitionists; with their support she reopened the school in April 1833 as a teacher- training institution for “young Ladies and little Misses of color,” as the advertisement announcing its opening noted. Crandall was twice arrested and tried under a new law that prohibited teaching blacks who were not state residents. Despite the indignity and concerted opposition—including a suspicious fire and pollution of the water supply—Crandall kept the school open until September 1834, when harassment of her students and a mob attack forced its closing.

Her subsequent life was peripatetic, her marriage unhappy, and her circumstances straitened. Finally, in 1886 the Connecticut state legislature sought to make amends by voting her a small pension. A supporter of temperance and woman suffrage in her later years, Crandall remained a woman of deep conviction. Her time in the limelight was short, but her story attests to the power of conscience in a just cause.

Ann Petry

Ann (Lane) Petry grew up in a warm, extended, and story-telling family in Old Saybrook, “a picture-postcard kind of town,” as she described it in a 1988 autobiographical essay. But African Americans were scarce, and racism shadowed family members, including Ann, who was stoned by some older boys on the first day of school. Petry took a degree in pharmacy (following in the tradition of her father and a maternal aunt; see “Destination: James Pharmacy,” Spring 2007, connecticutexplored.org/issues/vo5no2/pharmacy.htm), but she felt drawn to writing. Her goal took shape when she worked as a reporter and took writing classes in New York City, where she moved after her marriage. Her shock at conditions in Harlem is manifest in her first novel, The Street (1946), the searing story of Lutie Johnson, who seeks a better life for herself and her son but is defeated by the poverty and violence around her. In some respects the street was for Petry what the plantation was for Stowe: a brutal environment that deprived African Americans of freedom and destroyed their families.

The Street became a best seller and brought not altogether welcome fame to its author. Petry returned to Old Saybrook, where she wrote short stories, poems, and two more novels. She also wrote books for children and young adults to provide positive role models for her readers. Unlike “the walking wounded” who populate her adult fiction, these books feature “survivors,” among them Harriet Tubman, who helped slaves escape from bondage.

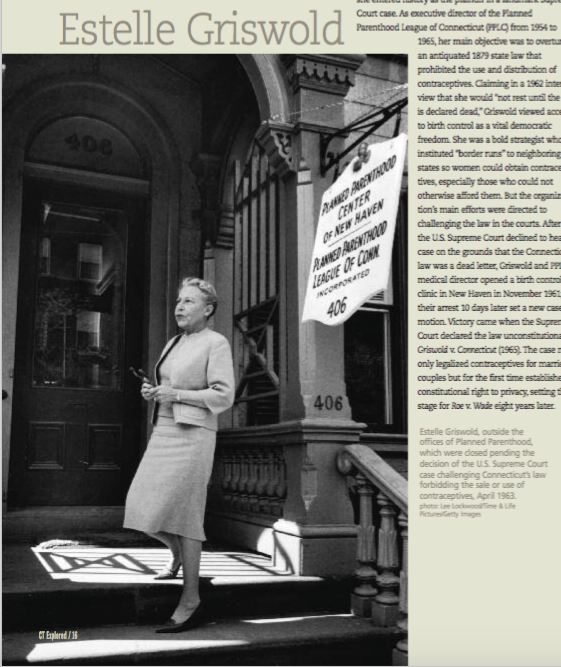

Estelle Griswold

Estelle (Trebert) Griswold set out to become a singer, but she entered history as the plaintiff in a landmark Supreme Court case. As executive director of the Planned Parenthood League of Connecticut (PPLC) from 1954 to 1965, her main objective was to overturn an antiquated 1879 state law that prohibited the use and distribution of contraceptives. Claiming in a 1962 inter-view that she would “not rest until the law is declared dead,” Griswold viewed access to birth control as a vital democratic freedom. She was a bold strategist who instituted “border runs” to neighboring states so women could obtain contraceptives, especially those who could not otherwise afford them. But the organization’s main efforts were directed to challenging the law in the courts. After the U.S. Supreme Court declined to hear a case on the grounds that the Connecticut law was a dead letter, Griswold and PPLC’s medical director opened a birth control clinic in New Haven in November 1961; their arrest 10 days later set a new case in motion. Victory came when the Supreme Court declared the law unconstitutional in Griswold v. Connecticut (1965). The case not only legalized contraceptives for married couples but for the first time established a constitutional right to privacy, setting the stage for Roe v. Wade eight years later.

See also, “Birth Control & Zones of Privacy,” Fall 2014

Catherine Roraback

Catherine Roraback views the law as a means of protecting individual rights and bringing about social change, commitments inspired in part by her feminist and pro-labor professors at Mount Holyoke College. After graduating from Yale Law School in 1948, she became a trial lawyer who took great delight in helping her clients. No case was too controversial. She defended Communists prosecuted under the Smith Act that made membership in the party illegal, a courageous stand during the McCarthy era. Her skillful representation of Black Panther Party leader Ericka Huggins, on trial for murder, ended in dismissal of the charges, an unexpected outcome in this high-profile case in the tense racial climate of New Haven in 1971. A passionate civil libertarian, Roraback was a founder of the Connecticut Civil Liberties Union, a board member of the ACLU, and president of the National Lawyers Guild.

She was also a feminist who helped advance women’s reproductive rights and the right of privacy, most notably as chief Connecticut litigator of the Planned Parenthood cases that culminated in Griswold v. Connecticut; she collaborated as well on a successful challenge to Connecticut’s anti-abortion law in 1971, two years before Roe v. Wade. An inspiration to many young women lawyers in her later years, Roraback delighted in encountering them in the formerly all-male bastion of the court.

See also, “Birth Control & Zones of Privacy,” Fall 2014

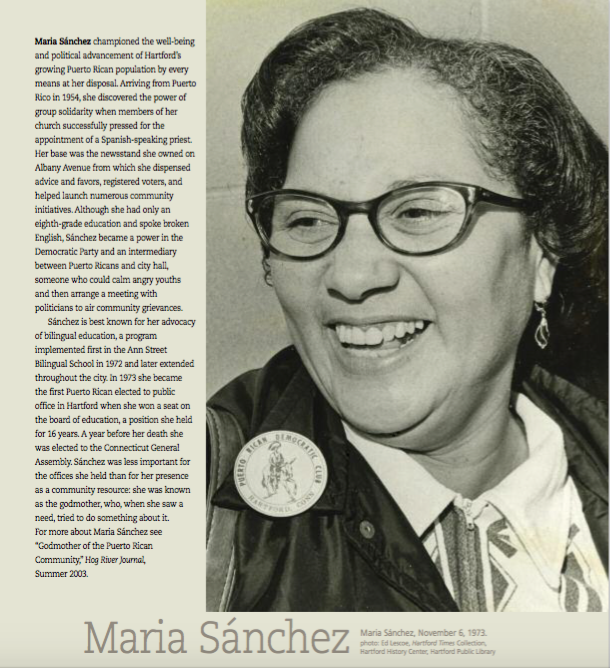

Maria Sánchez

Maria Sánchez championed the well-being and political advancement of Hartford’s growing Puerto Rican population by every means at her disposal. Arriving from Puerto Rico in 1954, she discovered the power of group solidarity when members of her church successfully pressed for the appointment of a Spanish-speaking priest. Her base was the newsstand she owned on Albany Avenue from which she dispensed advice and favors, registered voters, and helped launch numerous community initiatives. Although she had only an eighth-grade education and spoke broken English, Sánchez became a power in the Democratic Party and an intermediary between Puerto Ricans and city hall, someone who could calm angry youths and then arrange a meeting with politicians to air community grievances.

Sánchez is best known for her advocacy of bilingual education, a program implemented first in the Ann Street Bilingual School in 1972 and later extended throughout the city. In 1973 she became the first Puerto Rican elected to public office in Hartford when she won a seat on the board of education, a position she held for 16 years. A year before her death she was elected to the Connecticut General Assembly. Sánchez was less important for the offices she held than for her presence as a community resource: she was known as the godmother, who, when she saw a need, tried to do something about it.

For more about Maria Sánchez see “Godmother of the Puerto Rican Community,” Summer 2003.

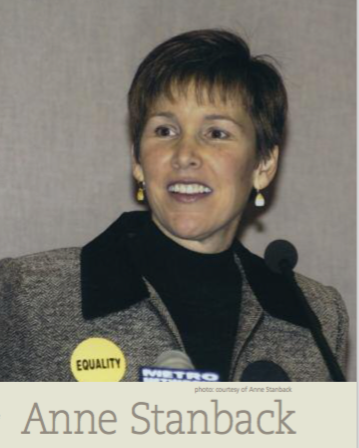

Anne Stanback

Anne Stanback has been an activist at least since her junior high school days in North Carolina, when she pressed for women’s tennis facilities that were equal in quality to those for men. She waged a similar campaign at Davidson College (also in North Carolina). Transplanted to Connecticut in 1982, she spent three years at Yale Divinity School, where she acquired the tools she needed for her future work as an advocate for social justice. She came out as a lesbian at this time. Stanback served as executive director of CT-NARAL, the Connecticut affiliate of the national abortion-rights organization, and the Connecticut Women’s Education and Legal Fund before becoming founding executive director of Love Makes a Family in 2000. After successfully lobbying for a co-parent adoption law, the organization focused on its primary goal: securing marriage equality for same-sex couples. Its tactics included grassroots organizing, community education, and house visits with legislators that aimed to demonstrate the humanity of gay and lesbian couples and their families by revealing the ordinariness of their lives and the harm done by denying them the right to marry. A tireless speaker and able strategist, Stanback personally helped to undermine negative perceptions by her persistence, persuasive logic, and gracious manner. Victory came in 2008 when the Supreme Court of Connecticut ruled that it was unconsti- tutional to deny same-sex couples the right to marry. Its objective achieved, Love Makes a Family disbanded the following year. Stanback is currently board chair of Freedom to Marry, an organization working to win marriage equality nationwide.

Barbara Sicherman is William R. Kenan Jr., Professor Emerita, Trinity College, where she taught history, Americanstudies, andwomen’s studies. Her most recent book, Well-Read Lives: How Books Inspired a Generation of American Women, was published in 2010 by the University of North Carolina Press. She has been a long-time trustee of the Harriet Beecher Stowe Center.

To learn more about the Connecticut Women’s Hall of Fame, visit www.cwhf.org.