by Elizabeth J Normen

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. SUMMER 2011

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

When Mark Twain built his dream house in Hartford’s Nook Farm neighborhood in 1874 his next-door neighbor was Harriet Beecher Stowe, the most famous American woman in the world. Twain was on the verge of international fame and would, while living in Nook Farm, write his most noteworthy books.

When Mark Twain built his dream house in Hartford’s Nook Farm neighborhood in 1874 his next-door neighbor was Harriet Beecher Stowe, the most famous American woman in the world. Twain was on the verge of international fame and would, while living in Nook Farm, write his most noteworthy books.

Twain described his first impressions of Nook Farm and Hartford in a letter to the San Francisco Alta California, January 25, 1868:

I am in Hartford, Connecticut, now…. I think this is the best built and handsomest town I have ever seen. … This is the centre of Connecticut wealth. Hartford dollars have a place in half the great moneyed enterprises of the union. All those Phoenix and Charter Oak Insurance Companies … are located here. The Sharp’s rifle factory is here; the great silk factory of this section is here; the heaviest subscription publishing houses in the land are here; and last and greatest, the Colt’s revolver manufactory is a Hartford institution.

Twain and Stowe brought unusual literary firepower to the neighborhood. But they took their place among an unusual enclave of citizens who were themselves well known on the national stage in politics and reform.

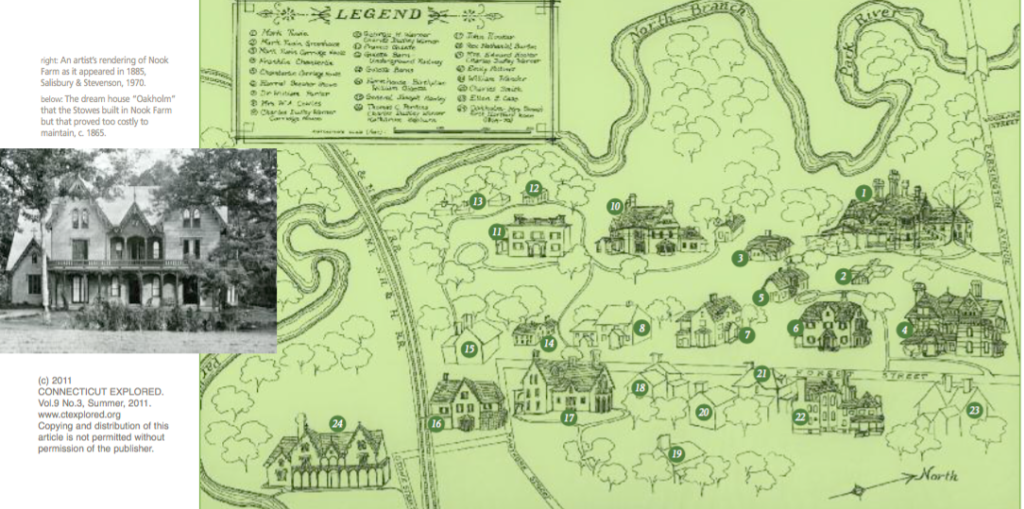

In 1853, Nook Farm was a 140-acre farm on the city’s western edge, bordered by Farmington Avenue, Sigourney Street, and the Hog (or Park, as it was later renamed) River. The Hartford and New Haven Railroad, built in the late 1830s, cut through the southern third of the parcel.

John Hooker of Farmington, a direct descendant of Hartford’s founder Thomas Hooker, and his brother-in-law Francis Gillette, descendant of a settler of Windsor, purchased the property that year from William Imlay with plans to develop it. Hooker was a lawyer married to suffragist and reformer Isabella Beecher Hooker. William Gillette, an abolitionist and fellow lawyer who later served as a one-term U.S. Senator, was married to Hooker’s sister Elizabeth.

Nook Farm developed into a tight-knit community through a web of family and business connections. It was both an oasis apart from the bustling city and a place that bubbled over with ideas about politics and reform during a time of great tumult in the nation.

Insert: Oakholm, c. 1865; Artist’s rendering of Nook Farm as it would have appeared in 1885, Salisbury & Stevenson, 1970. Harriet Beecher Stowe Center

In Nook Farm: Mark Twain’s Hartford Circle (Harvard University Press, 1950), Kenneth Andrews describes a neighborhood characterized by an easy and congenial lifestyle in which houses appeared scattered in a vast park rather than built on separate lots. Doors were always open; paths and shortcuts led through the woods from house to house, and homes were designed and furnished for frequent and informal visiting. Andrews observes that “Given swift current by independent points of view, through the parlors and studies of their houses flowed the main stream of national thought, with eddies of eccentricity forming in the corners.”

John and Isabella Beecher Hooker built the first new house in Nook Farm in 1853. Remarkably, this house still stands behind the apartment buildings on the corner of Forest and Hawthorne streets. The Gillettes remodeled the original Imlay farmhouse. Their son, the actor William Gillette (of Gillette’s Castle fame), was born there in 1853. In 1857, the young family built a large home a short distance northwest, with extensive grounds leading down to the river.

Isabella’s sister Mary Beecher Perkins and her husband Thomas—a lawyer under whom Hooker had studied—were the next to move to Nook Farm, building a house across Hawthorne Street, in 1855. Their sister Harriet and her family moved to the neighborhood in 1864 after Harriet’s husband Calvin retired from the Andover Theological Seminary—creating a female stronghold of the nationally prominent Beecher family. That year Harriet completed her Gothic-revival dream house “Oakholm” in the southern part of the neighborhood but was forced later to abandon it for a cottage on Forest Street, as the poorly built Oakholm turned out to be too expensive to maintain.

Isabella Beecher Hooker was prominent in her own right. A leader in the women’s suffrage movement, she organized a convention of the National Women’s Suffrage Association in Hartford in 1869 and in Washington, D.C. in 1871. She served as president of the Connecticut Women’s Suffrage Association (1871 to 1890) and invited national leaders such as Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Susan B. Anthony, and Victoria Woodhull to Nook Farm. In 1877, after a seven-year battle, she secured passage of a Connecticut bill establishing women’s legal right to hold property.

In 1860, John Hooker attracted a colleague, Joseph R. Hawley, and his wife Harriet Foote (a Beecher cousin) to an existing house on Hawthorne Street. Hawley began his career as a lawyer in Hooker’s firm but rose to prominence in Connecticut politics, organizing the Republican Party in the state in 1856. He founded the Hartford Evening Press (the Republican party organ) in 1857, and purchased The Hartford Courant in 1867, merging the two papers. He was a general in the Civil War and a war hero and narrowly won election as governor of Connecticut in 1866. He later served as a U.S. representative and, from 1881 to 1905, a U.S. senator. A year after he was elected governor he moved to nearby Sigourney Street.

In 1866, Hawley invited school chum and writer Charles Dudley Warner to Hartford to write for the Press and later the Courant. Warner had another connection to Nook Farm: His brother George had moved to the neighborhood after marrying Gillette’s daughter Elizabeth (Lilly) in 1864.

Playing croquet at the John & Isabella Hooker House, c. 1870. Harriet Beecher Stowe Center

Charles Warner gained national fame after publication of his My Summer in a Garden (1870). But today Warner is perhaps best known as co-author with Mark Twain of The Gilded Age (1873), the novel that gave the era its name. Marvin Felheim, in the introduction to the 1994 Meridian edition of The Gilded Age, relates how the book came to be: Over dinner one evening in 1872, the Clemenses and the Warners argued over the then-dominance of women in fiction writing by such authors as Harriet Beecher Stowe and Louisa May Alcott; Olivia Clemens and Susan Warner challenged their husbands to write a better novel.

Charles and Susan first lived in the Perkins house (the Perkinses had moved to nearby Woodland Street) but later moved into his brother’s house, built in 1873, when George and Elizabeth moved into her late parents’ house. The Perkins house would later be the childhood home of actor Katharine Hepburn.

Samuel Clemens visited Hartford in 1871 to arrange publication of his first book, Innocents Abroad, staying with John and Isabella Hooker, who were friends of Olivia’s mother. In 1872, he bought three acres of land in Nook Farm, eventually amassing eight acres. In 1873 and 1874, architect Edward Tuckerman Potter, architect of Elizabeth Colt’s Church of the Good Shepherd in Hartford, was kept busy with two commissions: the Clemenses’ 19-room, 5-bath house on Farmington Avenue, and the George Warners’ house to the rear. The Clemenses moved in in 1874. Their three daughters, Susie, Clara, and Jean, were all born in Nook Farm. During his time in Hartford, Twain wrote seven books, including The Adventures of Tom Sawyer (1876), Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (1885), and A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court (1889).

Lawyer and state representative Franklin Chamberlin built the two houses that are now part of the Stowe Center: the 1871 cottage where Harriet Beecher Stowe lived until her death, and the Chamberlin-Day House (1884). The Hartford Architecture Conservancy called the Day House “Hartford’s most fully developed example of the Queen Anne style.” It now houses the offices, archives, and program space for the Stowe Center.

Nook Farm was not just home to politicians and literary figures. Charles Boardman Smith, whose father had founded the Smith-Worthington Saddlery Co. in 1794 (see “Saddles Fit for a Shah,” Winter 2010/2011), and Newton Case, of Case Lockwood & Brainard printers, had large estates there. Today the Smith house serves as offices for the Mark Twain House staff.

Nook Farm’s golden age was over by the 1890s. Twain’s bad business speculations had ended his romance with Hartford, and the family moved away in 1891. Stowe, whose health had been in steady decline, died in 1896 at age 85. Farmington Avenue became an increasingly busy artery and was paved with asphalt in 1899, a sign that Nook Farm was becoming an urban neighborhood. The factories in the growing industrial area to the south belched smoke and pollutants into the Hog River. Lots were subdivided and houses and then apartment buildings erected. The Hog River was buried in concrete conduits up to Farmington Avenue in the early 1940s, and I-84 was built through the property in 1960. The Warner and Gillette houses, and nine others built after 1885, were taken by eminent domain to make way for the new Hartford Public High School, built in 1963 (the old one having also been torn down to make way for I-84). The Twain mansion housed apartments and a public library branch for a time.

Today we can get a sense of Nook Farm at its best through visits to the Mark Twain and Harriet Beecher Stowe houses and a self-guided walking tour of the neighborhood. We have another Nook Farm-style activist, Isabella’s granddaughter (and Harriet’s grandniece) Katharine Seymour Day, the ardent preservationist who founded the Stowe Center, to thank for that.

Elizabeth Normen is publisher of Connecticut Explored.

Explore!

Read “Saving Mark Twain’s House,” Spring 2013.

Read more Historic Preservation stories and stories about Notable Connecticans on our TOPICS pages.