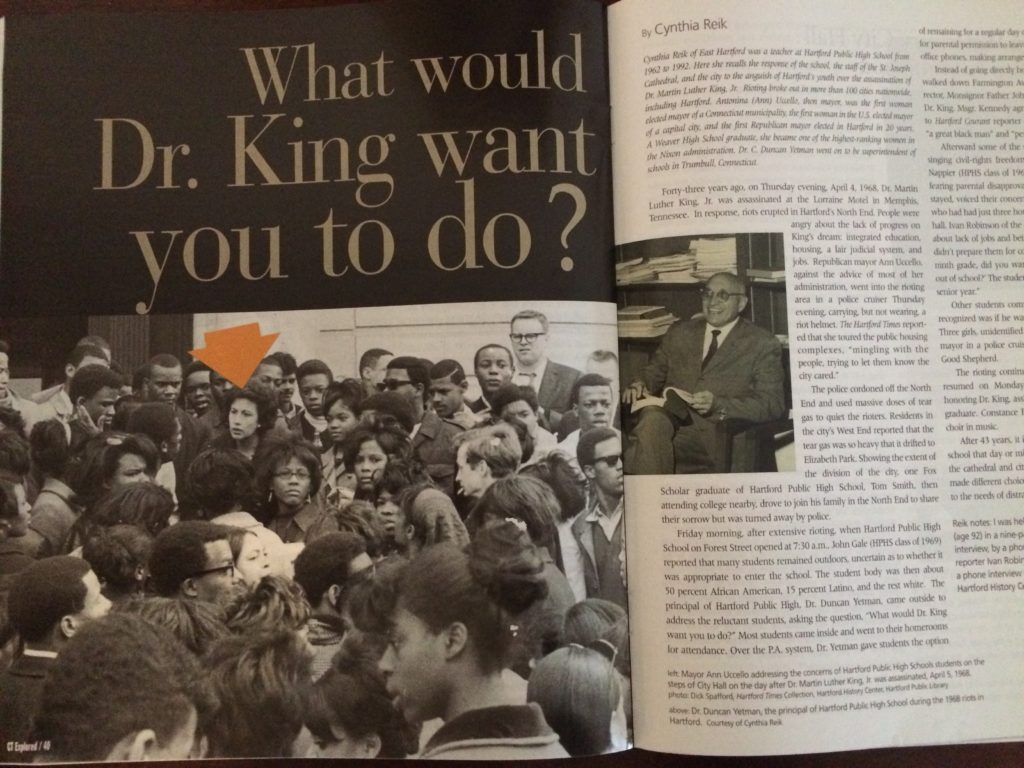

Mayor Ann Uccello addressing the concerns of Hartford Public High Schools students on the steps of City Hall on the day after Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. was assassinated, April 5, 1968. photo: Dick Spafford, Hartford Times Collection, Hartford History Center, Hartford Public Library. Right: Dr. Duncan Yetman, principal of Hartford Public High School during the 1968 riots in Hartford. courtesy of Cynthia Reik

By Cynthia Reik

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Fall 2011

SUBSCRIBE/BUY THE ISSUE

Cynthia Reik of East Hartford was a teacher at Hartford Public High School from 1962 to 1992. Here she recalls the response of the school, the staff of the St. Joseph Cathedral, and the city to the anguish of Hartford’s youth over the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Rioting broke out in more than 100 cities nationwide, including Hartford. Antonina (Ann) Uccello, then mayor, was the first woman elected mayor of a Connecticut municipality, the first woman in the U.S. elected mayor of a capital city, and the first Republican mayor elected in Hartford in 20 years. A Weaver High School graduate, she became one of the highest-ranking women in the Nixon administration. Dr. C. Duncan Yetman went on to be superintendent of schools in Trumbull, Connecticut.

Forty-three years ago, on Thursday evening, April 4, 1968, Dr. Martin Luther King was assassinated at the Lorraine Motel in Memphis, Tennessee. In response, riots erupted in Hartford’s North End. People were angry about the lack of progress on King’s dream: integrated education, housing, a fair judicial system, and jobs. Republican mayor Ann Uccello, against the advice of most of her administration, went into the rioting area in a police cruiser Thursday evening, carrying, but not wearing, a riot helmet. The Hartford Times reported that she toured the public housing complexes, “mingling with the people, trying to let them know the city cared.”

The police cordoned off the North End and used massive doses of tear gas to quiet the rioters. Residents in the city’s West End reported that the tear gas was so heavy that it drifted to Elizabeth Park. Showing the extent of the division of the city, one Fox Scholar graduate of Hartford Public High School, Tom Smith, then attending college nearby, drove to join his family in the North End to share their sorrow but was turned away by police.

Friday morning, after extensive rioting, when Hartford Public High School on Forest Street opened at 7:30 a.m., John Gale (HPHS class of 1969) reported that many students remained outdoors, uncertain as to whether it was appropriate to enter the school. The student body was then about 50 percent African American, 15 percent Latino, and the rest white. The principal of Hartford Public High, Dr. Duncan Yetman, came outside to address the reluctant students, asking the question, “What would Dr. King want you to do?” Most students came inside and went to their homerooms for attendance. Over the P.A. system, Dr. Yetman gave students the option of remaining for a regular day or coming down to the office to phone home for parental permission to leave school. For two hours students tied up the office phones, making arrangements to leave.

Instead of going directly home, however, four hundred or more students walked down Farmington Avenue to St. Joseph Cathedral and asked the rector, Monsignor Father John S. Kennedy, to hold a memorial service for Dr. King. Msgr. Kennedy agreed. During his impromptu service, The Hartford Courant’s reporter David Rhinelander wrote that Kennedy said, “the Rev. Dr. King was a great black man. He was ‘perhaps the greatest man of his generation.’”

Afterward some of the students continued down Farmington Avenue singing civil-rights freedom songs, arriving at noon at city hall. Donna Nappier (HPHS class of 1969) reported that some went home on the bus at this point fearing parental disapproval, as downtown was filled with rioters. Others stayed, voiced their concerns, and asked to see Mayor Uccello. The mayor, who had had just three hours sleep, greeted the students on the steps of city hall. Ivan Robinson of The Hartford Times reported the students “complained about lack of jobs and being given courses that, they suddenly discovered, didn’t prepare them for college. The mayor responded, ‘When you were in ninth grade, did you want to go to college or were you just dying to get out of school?’ The students admitted they didn’t think of college until their senior year.”

Other students complained that the only time a person of color was recognized was if he was good at sports or he was elected to a class office. Three girls, unidentified in the Hartford Times report, then accompanied the mayor in a police cruiser to a service for Dr. King at the Church of the Good Shepherd.

The rioting continued for most of the weekend. When high school resumed on Monday, Dr. Yetman conducted an all-school assembly honoring Dr. King, assisted by Msgr. Charles Daly, himself a Hartford High graduate. Constance Price, the choral director at the high school, led the choir in music.

After 43 years, it is unclear how many students may not have gone to school that day or might have joined the proactive group that marched to the cathedral and city hall. What is clear is that the students might have made different choices if it weren’t for the way the adult leaders responded to the needs of distraught young people.

Note: I was helped with this article by accounts given by Dr. Yetman (age 92) in a nine-page letter, by Ann Uccello (age 89) in a lunchtime interview, by a phone interview with David Rhinelander, an article by reporter Ivan Robinson, interviews with John Gale and Donna Nappier, a phone interview with Constance Price, and by resources provided by the Hartford History Center, Brenda Miller, and Martha Ray.

Explore!

Read more stories about childhood and the African American experience on our TOPICS page.