By Jon Blue and Henry Cohn

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Fall 2018

SUBSCRIBE/BUY THE ISSUE

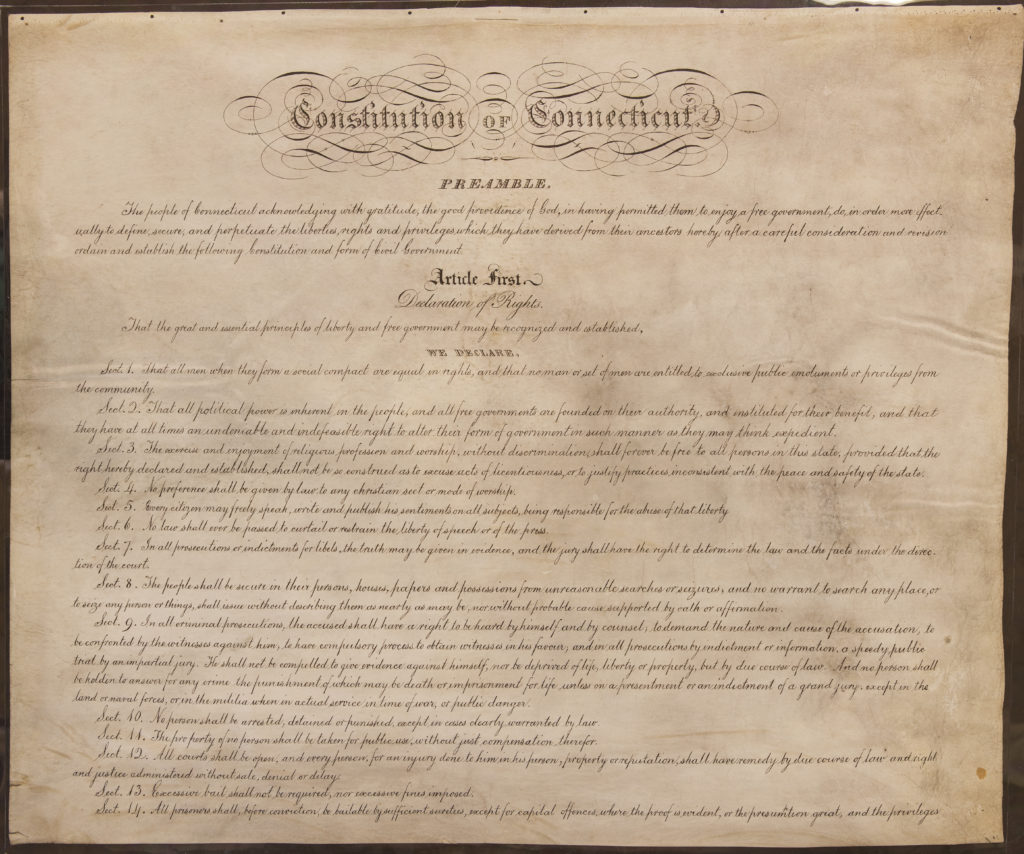

1818 was an important year in Connecticut. That was the year in which we adopted a state constitution. Although the Connecticut Constitution has been amended many times in the past 200 years, its basic protections remain pretty much unchanged. Because the constitution protects us all, it’s important not just for lawyers and judges but for ordinary citizens to understand. This very brief introduction to the Connecticut Constitution focuses on four things: what happened in 1818, the Declaration of Rights, our rights involving religion, and our rights involving education. Thanks to our constitution, every citizen of Connecticut enjoys these fundamental rights.

What Happened in 1818?

Unlike most of the original colonies, Connecticut did not adopt a constitution when it became a state. Instead, it continued to operate under a charter granted by King Charles II to the Connecticut Colony in 1662. Under the charter the general assembly had pretty much unchecked power. Although in other respects the way the state operated was extremely democratic in principle (elections were held every six months, for example), it didn’t quite work that way in practice.

As a practical matter, prior to 1817, Connecticut was governed by the Federalist Party under what was then called the Standing Order. The Standing Order was closely intertwined with the Congregational Church. States were not prohibited from having established churches at the time, and Connecticut was a prime example. The Congregational Church was supported by taxpayer money and was heavily involved in politics. Its ministers marched in processions, drank rum, and decided who got to be governor.

But the Federalists fell out of favor as a result of the War of 1812. They publicly opposed the war at the Hartford Convention of 1814 (see “The Notorious Hartford Convention,” Summer 2012). After Andrew Jackson won the Battle of New Orleans, the war became very popular, and the Federalists were sunk. In 1817 Oliver Wolcott Jr. was elected governor as the candidate of the Toleration Party. The Toleration Party wanted to disestablish the Congregational Church, and Governor Wolcott pushed for a constitutional convention to make this possible. In 1818 he got one.

The convention met in the Old State House in Hartford from August 26 to September 16, 1818. There were about 200 delegates, one or two from each town in the state. Governor Wolcott was elected president of the convention.

There was a 24-member drafting committee (3 members from each county), chaired by Pierpont Edwards, son of the great theologian Jonathan Edwards. The committee worked quickly, using a draft submitted by Governor Wolcott, the Charter of 1662, and the United States Constitution as models for its work. There were debates, just as in Philadelphia in 1787 (although not as dramatic). The convention made some changes to the committee’s draft on the floor and, on September 15, 1818, approved the finished product by a vote of 134 to 61.

The constitution had to be approved by a majority vote of the state’s electors. The vote was close. On October 5, 1818, the electors ratified the constitution by a vote of 13,918 to 12,364. The vote was pretty much along party lines, with Tolerationists voting yes and Federalists voting no. But as a result of the process the promise of the Preamble to the Connecticut Constitution was realized. The constitution was established by “the people of Connecticut.”

The Declaration of Rights

The Connecticut Constitution begins with a Declaration of Rights. The Declaration has remained surprisingly intact during the last 200 years. Although there is a substantial overlap with the Bill of Rights to the Federal Constitution adopted in 1791, the overlap isn’t complete. Connecticut’s Declaration of Rights contains some rights not provided in the federal version, and some rights that are provided in both versions have been treated more expansively by the Connecticut courts than by the federal courts.

Our Declaration of Rights contains three important rights not found in the Federal Bill of Rights. Section 1 provides “that all men when they form a social compact are equal in rights; and that no man or set of men are entitled to exclusive public emoluments or privileges from the community.” Section 10 provides that “No person shall be arrested, detained or punished, except in cases clearly warranted by law.” Section 12 provides that “All courts shall be open, and every person, for an injury done him in his person, property or reputation, shall have remedy by course of law, and right and justice administered without sale, denial or delay.”

So far, these additional rights have made surprisingly little difference in Connecticut judicial decisions. The big player, so far, has been the provision of Section 10 that “No person shall be arrested, detained or punished except in cases clearly warranted by law.” Connecticut courts have interpreted this provision as referring to rights set forth in statutes passed by the legislature. Neither this provision nor the social compact provision of Section 1 or the open courts provision of Section 12 have been construed to confer additional rights protected by the constitution itself.

In our view, this is a missed opportunity by our modern courts. Remember that the 1818 constitution was designed to break up the monopoly of a small clique of insiders running the state. The constitution was intended to achieve political and legal equality. The drafters of the state constitution lived in a relatively homogenous, largely agricultural society relatively free from the animosities caused by the extremes of wealth or poverty of today’s urban society. An elite Standing Order had controlled the state, but that coterie had been swept from political power. A recognition by our courts that the Connecticut Constitution was designed to address issues of inequality would be faithful to the document’s historical roots.

The real workhorses of the Connecticut Declaration of Rights have been a small group of important rights found in both the Connecticut and federal versions. These rights include the right to counsel in criminal cases, the right against unreasonable searches and seizures, and the rights to due process and equal protection of the law. (The right to equal protection was added in 1965.) We’ll give three examples.

In State v. Stoddard, decided in 1988, the Connecticut Supreme Court interpreted Connecticut’s right to counsel to require the police to tell a suspect being held for interrogation in a criminal case that his lawyer is trying to see him. The police had lied to Stoddard’s lawyer, telling him that Stoddard was not on the premises. Although federal law allows the police to engage in such trickery, the Connecticut court did not. Instead, the court cited Connecticut history and held that “this state’s commitment to securing the right to counsel has not diminished since 1818.”

While the Stoddard decision is mainly known to lawyers, many ordinary citizens have had their lives changed by Kerrigan v. Commissioner of Public Health, a 2008 decision allowing same-sex couples to marry. Kerrigan ruled that the protections of Connecticut’s equal protection clause go beyond that provided by its federal counterpart. (The United States Supreme Court had not yet held that same-sex marriages are allowed by the Federal Constitution.) It explained that “The drafters of our constitution carefully crafted its provisions in general terms, reflecting fundamental principles, knowing that a lasting constitution was needed.” Consequently, “our conventional understanding of marriage must yield to a more contemporary appreciation of the rights entitled to constitutional protection.”

The 2015 case of State v. Santiago provides a final example. Santiago, as is well known, held that capital punishment, as currently applied, violates the Connecticut Constitution. Although the Declaration of Rights does not contain an explicit protection against cruel and unusual punishment, the Connecticut courts have long held that the right to due process of law, which iscontained in the Declaration of Rights, incorporates “principles of fundamental fairness rooted in our state’s unique common law, statutory, and constitutional traditions.” It noted that the 1818 Constitution was drafted during a period of “penological reform, an emerging commitment to human rights, and the first widespread public questioning of the moral legitimacy of capital punishment.” Since then our history has evinced “a steady, inexorable devolution in the popularity and legitimacy of the death penalty.” It consequently held that our current system “fails to comport with our abiding freedom from cruel and unusual punishment.”

Whether you agree or disagree with these decisions, it is clear that the Declaration of Rights has a profound effect on the everyday lives of countless citizens of Connecticut.

Religion

The 1818 constitution addressed issues of religion in two different ways. First, Section 3 of the Declaration of Rights provided that the “exercise and enjoyment of religious profession and worship without discrimination, shall forever be free to all persons in this state” [but that right]“shall not be so construed as to excuse acts of licentiousness or justify practices inconsistent with the peace and safety of the state.” Second, Article 7 addressed taxpayer support of churches.

The language regarding free exercise was based on earlier legislation and court cases. Zephaniah Swift, in Volume I of his System of the Laws of the State of Connecticut (1795),relied on the 1784 Conscience Act. He concluded that liberty of conscience was granted to Christians of every denomination, as well as Jews, “Mehometans,” and “Brahmins.”

Abington Congregational Church, Pomfret. The Greek Revival-style church was built in 1751, making it one of the oldest standing ecclesiastical buildings in Connecticut and one of the few surviving examples of 18th-century peg-and-beam construction in New England. The steeple and bell were added in 1802, and the church was done over in the Greek Revival style in 1840. photo: Lewis Mills, Connecticut State Library

The main purpose of the 1818 Constitutional Convention was to disestablish the Congregational Church. Even the Congregationalist delegates supported Article I, Section 3. Delegate John Treadwell, a former governor and devout Congregationalist, declared at the convention that there should be free exercise of religion. “Papists, Mahommedans, Jews, or Hindoos should be allowed to meet together and tolerated.” The language of Article I, Section 3 is identical to that found in the current 1965 constitution.

The First Amendment to the United States Constitution contains a clause forbidding the establishment of religion. The drafting committee recommended a similar clause, proposing for Article I, Section 4 that “[n]o preference shall be given to any religious sect, or mode of worship.” But Treadwell and fellow delegate Pierpont Edwards won a debate in which they were opposed by Governor Wolcott and Rev. Agahel Morse, who were aligned with the Baptists and Methodists, respectively. Treadwell’s side convinced the delegates to substitute the word “Christian” for “religious.” Treadwell, in an address to the convention, advocated this change to emphasize the preferred position of the Christian over other, non-Christian religions. Treadwell, caught up in a view that he must defend a public commitment to old time “Puritanism,” actually made Section 4 meaningless. As finally adopted, this section prohibited only a Christianestablished religion. By its own words, it would permit the official establishment of a non-Christian church and because of the adoption of Section 3, Section 4 merely became a token remnant of the Standing Order and had little effect.

In any event, the incorporation of the federal First Amendment’s establishment clause made the article obsolete, and the First Amendment’s establishment clause controls today. Also, Article VII of the 1965 Constitution states that no preference should be given to any religious denomination in this state. Courts have ruled that this is equivalent to the federal establishment clause. On the other hand, Article I, Section 4 remained a part of the Connecticut law until it was repealed in the 1965 Constitution.

Article 7 of the 1818 Constitution addressed another religious issue. Under the “Standing Order” of the Connecticut theocracy, the Congregational Church benefited from town taxation. Article 7 attempted to resolve the finances and membership of the town churches once there was no longer a single, central church. Treadwell and his followers expressed fears that allowing each church to handle its own affairs would undercut all ecclesiastical societies in the state; it would amount to the end of “excellent old government.” The convention delegates debated the issue and were again influenced by Treadwell. Article 7 provided in Section 1 that since it was the duty of all to worship a supreme being in accordance with their conscience, no person would be compelled to join or support any church or religious association. But anyone now belonging to such an institution “shall remain a member thereof until he separates himself therefrom.” In addition, each Christian denomination had equal authority to support ministers and teachers of their denomination, and to build and repair houses for public worship “by a tax on members of any such society only, to be laid by a major vote of the legal voters assembled at any society meeting . . . .”

Section 2 provided that a person could leave a denomination of Christians to which he belonged by giving written notice to the church clerk, at which point he would “thereupon be no longer liable for any future expenses which may be incurred by said society.” The mandatory duty to support the Congregational Church thus came to an end. The 1965 Constitution retained some of the language of the 1818 Constitution, regarding non-compulsion, but dropped the taxation grant as well as the method of resignation through the church clerk.

Education

The 1818 Constitution addressed the topic of education in Article 8. The education of children was always important for the Connecticut authorities and its citizens. In Volume 2 of his System of Laws (1796),Swift stated that “[t]he neglect of the education of children, may be deemed criminal, when so many thousand volumes have been written, to prove the importance of that duty.”

Article 8, Section 1 provided that the charter of Yale University, established in 1792 by the legislature, was confirmed. Oliver Wolcott’s suggested draft further provided that the legislature could incorporate other institutions to promote science, literature, the arts, and religion, but this draft provision was not included in the final document.

Union School, New London, as it appeared before 1830. Nathan Hale taught here briefly, from 1774 to 1775, in the schoolhouse’s first years. The schoolhouse was in use until around 1880. Connecticut Sons of the American Revolution

Article 8, Section 2 concerned the “School Fund.” The School Fund originated in 1733 when the legislature determined that proceeds from a sale of seven townships within Litchfield County be used for education purposes. The interest from the proceeds was to be applied to the support of common schools in Connecticut. In 1765 additional funds were generated from interest on taxation of certain goods.

In 1795 the school fund received major support from the sale of Connecticut’s “Western Reserve.” This was land in northern Ohio that Connecticut had claimed under its 1662 charter (see “West of Eden: Ohio Land Speculation Benefits Connecticut Public Schools,” Summer 2007). Treadwell had negotiated the sale for $1.2 million. He supported the School Fund while serving in the state legislature and was also one of the members of the board of managers to administer the fund.

The delegates were concerned—apparently from experience—that the school fund might be diverted to non-education uses. Wolcott’s draft called for the fund to be “inviolably appropriated” and for accountability for the funds by the state comptroller and the school districts benefitted by the fund. Article 8, Section 2 as adopted was succinct but similar, providing that “the fund, called the SCHOOL FUND, shall remain a perpetual fund, the interest of which shall be inviolably appropriated to the support and encouragement of the public, or common schools throughout the state, and for the equal benefit of all the people thereof.” The amount of the fund was to be recorded in the state comptroller’s office, “and no law shall ever be made, authorizing said fund to be diverted to any other use than the encouragement and support of public, or common schools, among the several school societies, as justice and equity shall require.”

In the 1970s through the 1990s, several cases, notably Horton v. Meskill(1977), arose around the duty of the state to provide free elementary and secondary public education and how to finance it. In confirming this duty, the Connecticut Supreme Court pointed to the educational requirements of Article 8.

In the 1970s through the 1990s, several cases, notably Horton v. Meskill(1977), arose around the duty of the state to provide free elementary and secondary public education and how to finance it. In confirming this duty, the Connecticut Supreme Court pointed to the educational requirements of Article 8.

Constitution of 1965

In 1965 the 1818 Constitution was replaced after the federal courts held in 1964 that the its provisions establishing the number of state representatives led to unconstitutional apportionment, based on population. For example, the small town of Union and the large city of Hartford were each allotted two state representatives. While the 1965 Constitutional Convention delegates remedied this problem, they left the other provisions of the 1818 Constitution largely intact. Today, as 200 years ago, Connecticut’s Declaration of Rights, its separation of powers into three branches, its regard for freedom of religion and education, and the right to a jury trial, made part of the 1818 Constitution, still remain and protect us all.

Jon Blue is a judge for the Connecticut Superior Court and author of The Case of the Piglet’s Paternity: Trials from the New Haven Colony, 1639 – 1663(Wesleyan University Press, 2015).Henry Cohn is a former judge of the Connecticut Superior Court and presently serves as a judge trial referee. He last wrote “Divorce Connecticut-Style” (Winter 2017-2018).

READ MORE!

For more on the Constitution of 1965, see “Reflections on the 1965 Constitutional Convention” by Larry DeNardis