By Cathy J. Schlund-Vials

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Fall 2013

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

On December 7, 1941, a date that would “live in infamy,” the Imperial Japanese Navy launched a surprise military strike against the United States. The bombing of Pearl Harbor signaled the official start of U.S. involvement in World War II. It also marked a profound change in fortunes for Japanese Americans in California, Oregon, and Washington.

Though Curtis B. Munson’s “Report on Japanese on the West Coast of the United States” (1940) stressed that first- and second-generation Japanese Americans posed no security threat, on February 19, 1942, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066. The order enabled the forced relocation and incarceration of an estimated 110,000 Japanese Americans. Two-thirds of those interned were U.S. citizens; the remaining third were first-generation immigrants. The Japanese American internment (1942-1946) remains a potent reminder of racialized wartime anxiety.

Though Curtis B. Munson’s “Report on Japanese on the West Coast of the United States” (1940) stressed that first- and second-generation Japanese Americans posed no security threat, on February 19, 1942, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066. The order enabled the forced relocation and incarceration of an estimated 110,000 Japanese Americans. Two-thirds of those interned were U.S. citizens; the remaining third were first-generation immigrants. The Japanese American internment (1942-1946) remains a potent reminder of racialized wartime anxiety.

In March 1942, President Roosevelt formed a new civilian agency: the War Relocation Authority (WRA). The WRA was charged with the administration of the so-termed “evacuation” effort, which included documenting—by way of film and photography—the en masse relocation of Japanese Americans.

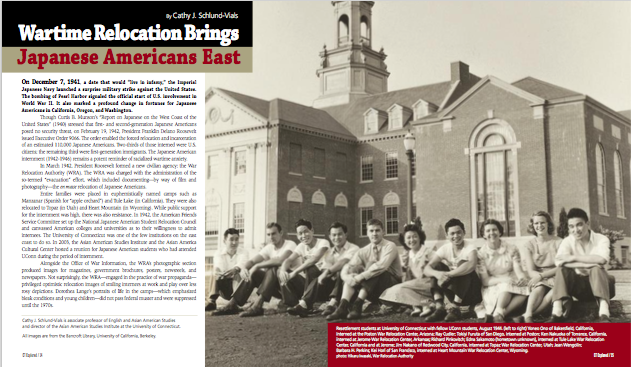

Entire families were placed in euphemistically named camps such as Manzanar (Spanish for “apple orchard”) and Tule Lake (in California). They were also relocated to Topaz (in Utah) and Heart Mountain (in Wyoming). While public support for the internment was high, there was also resistance. In 1942, the American Friends Service Committee set up the National Japanese American Student Relocation Council and canvassed American colleges and universities as to their willingness to admit internees. The University of Connecticut was one of the few institutions on the east coast to do so. In 2003, the Asian American Studies Institute and the Asian America Cultural Center hosted a reunion for Japanese American students who had attended UConn during the period of internment.

Alongside the Office of War Information, the WRA’s photographic section produced images for magazines, government brochures, posters, newsreels, and newspapers. Not surprisingly, the WRA—engaged in the practice of war propaganda—privileged optimistic relocation images of smiling internees at work and play over less rosy depictions. Dorothea Lange’s portraits of life in the camps—which emphasized bleak conditions and young children—did not pass federal muster and were suppressed until the 1970s.

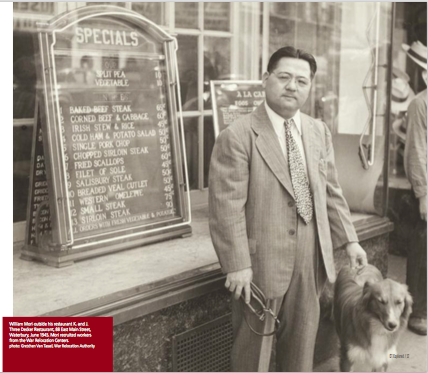

William Mori outside his restaurant in Waterbury, June 1945. photo: Gretchen Van Tassel, War Relocation Authority

As Japan’s military might began to fade in the Pacific Rim, the U.S. government launched a phased resettlement program in 1943. According to historian Lane Ryo Hirabayashi in Japanese American Resettlement Through the Lens: Hikaru Carl Iwasaki and the WRA’s Photographic Section, 1943-1945 (University Press of Colorado, 2009), during this phase, “the focus shifted from removal and concentration to resettlement.” Japanese Americans would fulfill labor demands at home and abroad as per the ongoing war effort. In January 1943, Japanese American men were allowed to enlist in the U.S. Army, and almost 6,000 volunteered for the war effort. In February 1943, all internees aged 17 and older were required to answer a “loyalty questionnaire” wherein applicants swore “unqualified allegiance” to the United States. Upon proving their loyalty, men, women, and children were allowed to leave the camps.

Created under the aegis of the WRA, the wartime images on the following pages highlight the “fair” treatment of Japanese Americans in contrast to fascist authoritarianism in Europe and Japan. Some Japanese Americans chose to relocate to Connecticut and other states in the Midwest. Some ventured back to their West Coast homes, only to find them vandalized or destroyed.

Between 1943 and 1945, WRA photographed “all aspects of resettlement,” including images of “Japanese students, workers, and soldiers.” As the images here make clear, Connecticut figures prominently in the history of Japanese American resettlement. In an interview with Hirabayashi, WRA photographer Kikaru Iwasaki, who took more than 1,300 resettlement pictures (including the UConn portrait included here), stressed that he wanted to provide a counter-narrative to the internment by providing uplifting, hopeful images of post-camp Japanese American life. Other photographers likely concurred, and their images reflect smiling, seemingly happy people such as the former internees recruited by William Mori, a successful restaurateur in Waterbury, Connecticut. From Bridgeport to Fairfield, from Old Lyme to Storrs, Japanese Americans worked in hotels, on estates, and in factories.

Mr. & Mrs. Shigeko Sakamoto and their son Shirori, Fairfield, June 1945. photo: Gretchen Van Tassel, War Relocation Authority

Though the WRA photos were intended to promote the war effort at home and abroad, it is important to acknowledge their emotional value outside the strict confines of wartime propaganda. The trauma of forced relocation, along with the depressing conditions of camp life, were largely absent from the public discourse. Thus, positive resettlement images were in some cases intended to boost morale for those still “in camp” while highlighting to the nation at large the extent to which Japanese Americans were “model” Americans.

Cathy J. Schlund Vials is associate professor of English and Asian American Studies and director of the Asian American Studies Institute at the University of Connecticut.