By Steven Slosberg

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Summer 2012

Subscribe/Buy the Issue

In January 1814, the Connecticut Gazette of New London carried a dispatch from Washington, D.C. about a clamor in Congress to investigate a maddening wartime phenomenon surrounding what came to be known as “blue lights.” Six months earlier, U.S. Commodore Stephen Decatur and his squadron of three ships had dodged the British blockade of New London’s harbor and taken safe haven a few miles up the Thames River. Each of his stealthy attempts to escape his confined position had been thwarted by the appearance of warning signals in the form of two blue lights, which were dramatically described in the Gazette’s January 24 report from Washington as “these wicked lights, these torches of treason.” Who was lighting these “torches of treason,” and why?

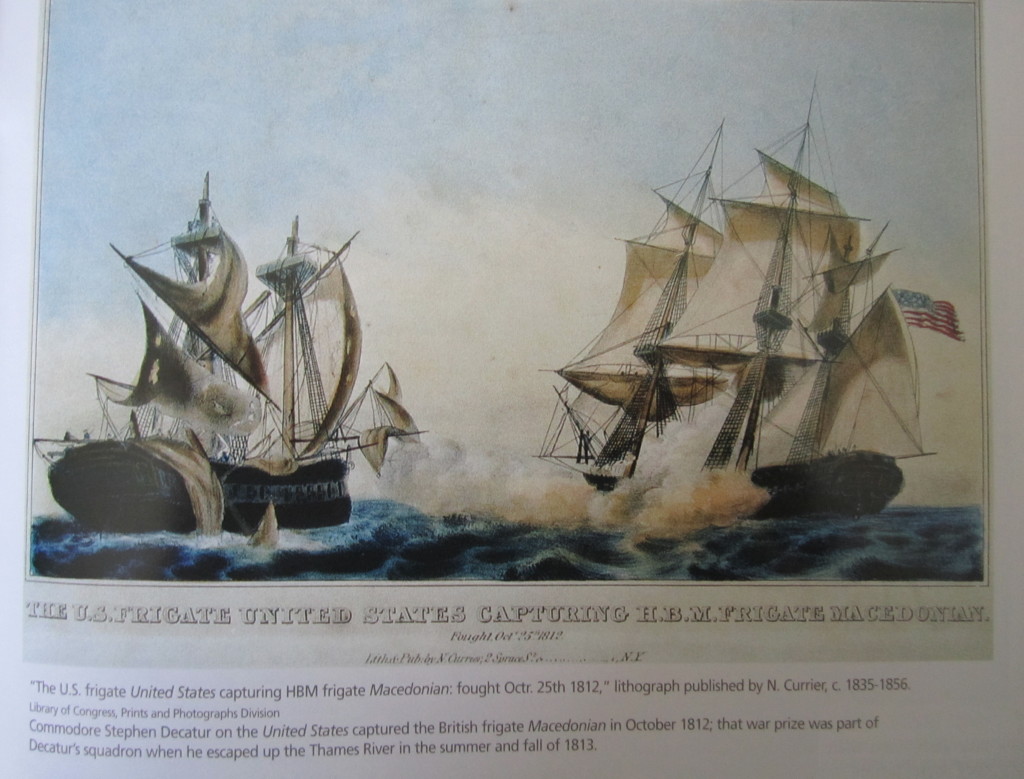

The US frigate United States capturing HBM frigate Macedonian, October 25, 1812. N. Currier, c. 1835-1856. Library of Congress

In 1813, U.S. Secretary of the Navy William Jones had dispatched Decatur, hero of Barbary wars at Tripoli in 1803-1804 and conqueror of the British warship Macedonian in 1812 off the Canary Islands, to draw off blockaders along the eastern seaboard by attacking British commerce in the West Indies. According to Joseph A. Goldenberg in “Blue Lights and Infernal Machines: The British Blockade of New London,” (in Mariner’s Mirror, November 1985), Decatur sailed out of New York in June aboard his frigate United States, accompanied by the refitted prize Macedonian and the sloop Hornet. But he didn’t get far. He encountered British warships off Block Island and Montauk Point and elected to duck into New London, protected by two forts on opposite sides of the Thames River, Fort Griswold in Groton and Fort Trumbull in New London. After grounding on the river bottom at the start of his passage, Decatur maneuvered the three ships eight miles upstream to Allyn’s Point in Gales Ferry. He bargained that the heavy British warships wouldn’t risk pursuit. But his action also insured that those same warships would remain vigilant off New London. In short, Decatur was safe, but stuck.

As a result, “The city of New London and its environs, dependent largely upon an infant whaling industry and seaborne commerce of all types, fell upon extremely hard times,” writes Navy Lieutenant Commander Douglas S. Jordan in his article “Stephen Decatur at New London: A Study in Strategic Frustration” (Proceedings, U.S. Naval Institute, October 1967). Instead of being treated as heroes, Jordan writes, “… As the focal point of the local blockade, Decatur and his crews found themselves the subject of scathing remarks implying cowardice, duplicity, and other invectives of the like.”

Fearing the British might come after him by land, Decatur had teams of oxen lug weapons up a hill overlooking the river to what became known as Fort Decatur (see sidebar). With the arrival of autumn and longer hours of darkness, Decatur began making preparations to try to run the blockade. In October the three ships began moving downstream, and by mid-November they were anchored in New London Harbor. Decatur chose the night of December 12 to make his run.

As James Tertius de Kay recounts in The Battle of Stonington: Torpedoes, Submarines and Rockets in the War of 1812 (Naval Institute Press, 1990), “On 12 December an overcast sky and lack of moon guaranteed the total darkness Decatur needed.” The squadron, along with smaller guard boats, cautiously moved out. Not far from the harbor was the palatial New London home of British consul James Stewart and his wife, Elizabeth Coles Stewart. The Stewarts’ residence, set on a rise at Winthrop’s Neck with a view of the length of Winthrop Cove to Fishers Island Sound, was the venerable Winthrop Homestead, built in the 1750s by descendants of New London’s founder, John Winthrop, Jr.

Decatur’s squadron approached the mouth of the river. “As the guard boats rounded the point,” writes de Kay, “a whispered word from the after watch caused one of the officers to turn back toward Fort Trumbull, where he saw the one thing he most dreaded seeing … a small but unmistakable blue signal light.” A second blue light appeared on the other bank of the Thames, near Fort Griswold. “An angry, embittered, miserable commodore ordered his ships back up the Thames…. Mrs. Stewart and her people had earned their pay that night.”

De Kay asserts that James and Elizabeth Stewart kept the British apprised as to what was afoot on land and that federal officials eventually ordered James Stewart out of town for suspected espionage. “After the abrupt departure of Mr. Stewart,” wrote de Kay, “Mrs. Stewart took over his position as spy master, and she and her agents made New London the conduit for an almost endless stream of American intelligence reaching the entire [British] fleet.” Could Elizabeth have been behind the “the wicked lights, the torches of treason?”

“Blue lights,” the term Decatur used in his damning letter to the Secretary of the Navy, dated December 20, 1813, are defined by the Oxford Companion to Ships and the Sea (Second Edition, Oxford University Press, 1976) as “A pyrotechnical preparation … used at night, in conjunction with gunfire, to transmit orders of the admiral of a squadron or fleet. By counting the number of gunshots fired, and observing the blue lights shown, the captain of a man-of-war could interpret through his night signal book what order the admiral was making.”

“Blue lights,” the term Decatur used in his damning letter to the Secretary of the Navy, dated December 20, 1813, are defined by the Oxford Companion to Ships and the Sea (Second Edition, Oxford University Press, 1976) as “A pyrotechnical preparation … used at night, in conjunction with gunfire, to transmit orders of the admiral of a squadron or fleet. By counting the number of gunshots fired, and observing the blue lights shown, the captain of a man-of-war could interpret through his night signal book what order the admiral was making.”

To Decatur, the situation was clear: His squadron’s movement had been betrayed to the British. But not everyone supported his conclusion. In the U.S. Congress, Connecticut representatives Lyman Law and Jonathan Moseley, members of the Federalist Party, pushed for a congressional investigation. The Gazette’s account suggests that the two lawmakers were irked not only by reports that the “blue lights” episode had actually occurred but by the implication that the citizens of New London might have been party to such an outrageous betrayal. They sought the probe mostly to salvage New London’s good name. In the end, despite a smattering of support from mid-Atlantic and southern congressmen, the motion to launch an inquiry was tabled. Congressman John C. Calhoun of South Carolina, one of the “War Hawks” who had agitated for what became the War of 1812, declared that it was much ado about nothing. “Too diminutive” were the words attributed to Calhoun in the newspaper account.

But in New London, the “blue lights” controversy burned on.

Because many members of the Federalist Party opposed the war and advocated peace with Britain, those party members were soon labeled, derisively, “Blue Light Federalists,” and there were suggestions they were behind the signals. Samuel Green, the editor of the Connecticut Gazette, confronted by angry townspeople who refused to believe in lights or traitors, was sympathetic to Decatur and chastised the nay-sayers in his newspaper: “Some petulant scribblers of this place continue through the Boston prints to trouble the public and disturb good neighbors with their whim-whams about the blue lights.”

But in his Proceedings piece, Jordan seems swayed by the skeptics: “… many believed the lights were shown from fishermen pursuing their peaceful trade, or perhaps were merely the reflection of the setting sun.… It was said that similar signals were again displayed in January and answered by the British ships, but no one was ever accused of the crime, and no proof was offered on either side to support or disprove the Commodore’s report.” Perhaps Decatur, once a hero, had proven inept and had hatched an excuse to mitigate his failure to run the blockade.

In April 1814, Decatur moved the United States and Macedonian back up river, dismantled them, and returned to New York by land where he was given another command, the President. The British blockade of New London would sustain until early March 1815, when British ships finally departed after the February 22 official celebrations of the signing of the Treaty of Ghent, which ended the war. Decatur, after the war, served again at sea in North Africa. In 1820, he died in a duel in his home state of Maryland.

James and Elizabeth Stewart had a protracted departure from New London, including lengthy separations and intervention with the U.S. government on Mrs. Stewart’s behalf by Captain Sir Thomas Hardy, commander of the British blockade flagship Ramillies. Once reunited, the Stewarts retired to Great Britain, where, as de Kay wrote, “a grateful crown provided [Stewart] and his wife with a pension, chiefly in recognition of Mrs. Stewart’s outstanding espionage work during the war.”

What Commodore Stephen Decatur vowed his fellow officers and crew members saw, or didn’t see, on that dark December night in 1813, and what Elizabeth Stewart and other loyalists in New London did, or didn’t do, remain the stuff of conjecture, debated in Congress a month after the episode and argued still by contemporary historians. But what has been established is that the war was hardly popular in a port city such as New London, which was dependent on a free-flowing harbor for much of its commerce and chafed under the Decatur-centric blockade. Whether politics or pyrotechnics, the “blue lights” do, indeed, burn on.

Steven Slosberg, a journalist and columnist who worked for The Day of New London for three decades, lives in Stonington.

Explore!

Site Lines: Fort Decatur, Summer 2012

Read all of our stories about Connecticut in the War of 1812 in our Summer 2012 issue

Read all of our stories about Connecticut at War on our TOPICS page