By Nancy Steenburg

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. SUMMER 2012

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

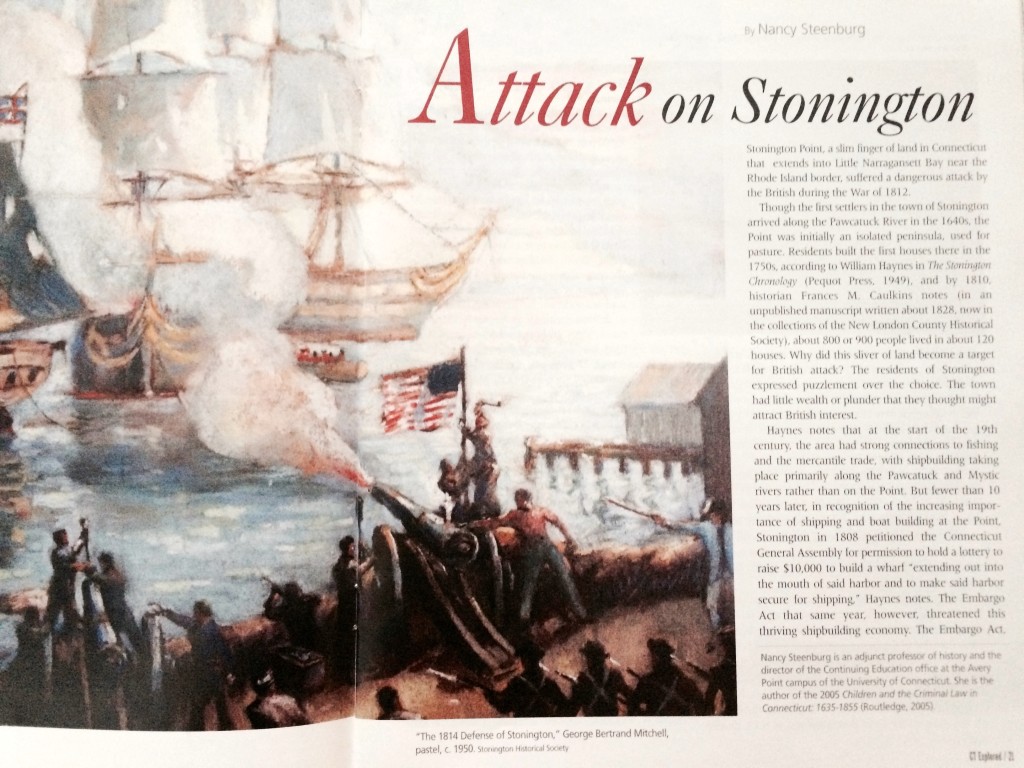

Stonington Point, a slim finger of land in Connecticut that extends into Little Narragansett Bay near the Rhode Island border, suffered a dangerous attack by the British during the War of 1812. Though the first settlers in the town of Stonington arrived along the Pawcatuck River in the 1640s, the Point was initially an isolated peninsula, used for pasture. Residents built the first houses there in the 1750s, according to William Haynes in The Stonington Chronology (Pequot Press, 1949), and by 1810, historian Frances M. Caulkins notes (in an unpublished manuscript written about 1828, now in the collections of the New London County Historical Society) about 800 or 900 people lived in about 120 houses. Why did this sliver of land become a target for British attack? The residents of Stonington expressed puzzlement over the choice. The town had little wealth or plunder that they thought might attract British interest.

Haynes notes that at the start of the 19th century, the area had strong connections to fishing and the mercantile trade, with shipbuilding taking place primarily along the Pawcatuck and Mystic rivers rather than on the Point. But fewer than 10 years later, in recognition of the increasing importance of shipping and boat building at the Point, Stonington in 1808 petitioned the Connecticut General Assembly for permission to hold a lottery to raise $10,000 to build a wharf “extending out into the mouth of said harbor and to make said harbor secure for shipping,” Haynes notes. The Embargo Act that same year, however, threatened this thriving shipbuilding economy. The Embargo Act, passed by the United States Congress, aimed to minimize potential conflict with both Britain and France by forbidding Americans from trading with any foreign ports. The Act had relatively little impact on foreign powers but nearly destroyed New England’s shipping trade. Despite that legislation’s widespread unpopularity and the devastating impact it would have on the town’s economy, on March 27, 1809 the town voted to obey the Embargo Act.

The War of 1812 became a reality for Connecticut citizens living along the coast in the summer of 1813, when a British squadron began patrolling Long Island Sound, seizing fishing and merchant ships, and generally blocking coastal communities from pursuing their livelihood on the sea. Several times that summer Stonington militia members marched to New London to help repel attacks, none of which materialized there.

Caulkins asserts that no one in Stonington anticipated a British attack because the town was small and had little of interest that the British might want to plunder. Still, in June 1813, the State of Connecticut sent two 18-pound cannons for the defense of the harbor. Caulkins describes the breastworks where the cannons were mounted as a small semi-circular stone wall, three or four feet high, built by local residents, who also erected a flagpole by the battery. All was quiet on the Point during the rest of 1813, despite the British troops’ seizing many ships that were trying to escape the blockade on Long Island Sound.

In May1814 the town of Stonington increased its defenses, setting up a tar-barrel signal pole at a high point in the northern part of town (now north of state Route 95) and maintaining a militia guard of 41 men. The townspeople were on edge, living in anticipation until the first act of war occurred on July 30. According to Haynes, ships of the British squadron chased a privateer into Stonington Harbor, but the militia drove the British off, killing British midshipman Thomas Powers. The town allowed his burial with honors in the Stonington Cemetery. Less than two weeks later, full-scale war arrived at the Point.

In mid afternoon on August 9, 1814, four British ships anchored off Stonington Point: H.M.S. Ramillies with 74 guns, Pactolus with 44 guns, Dispatch with 22 guns, and the bombship Terror, all under the command of Captain Thomas M. Hardy. Hardy sent an ultimatum to the town: “Not wishing to destroy the unoffending inhabitants residing in the town of Stonington, one hour is granted them from the receipt of this to remove out of town.” The time on Hardy’s note was 5:30.

Some people did leave, according to Caulkins. Women and children carrying hastily collected possessions fled the village, many of them crying in fear and anxiety. Most took shelter in the neighboring fields, woods, barns, and farmhouses. Some went as far as Montauk Hill, where many stayed in the open. Caulkins noted that the mild August weather allowed the fleeing families to remain nearby, where they anxiously awaited the outcome of the British attack. The timorous may have fled, but according to Haynes, some Stonington men stayed behind and set the tar-barrel signal smoking to alert the militia in nearby towns.

The first defenders rushed to the breastworks, small protection against the combined firepower of four ships of the British Navy. Town residents William Lord, Asa Lee, George Fellows, and Amos Denison manned the three cannons. By 6 p.m. 16 volunteers from Mystic joined the original 4, including Captain Jeremiah Holmes, a vital addition to the ranks of the defenders. Holmes, a Mystic native, had suffered impressment at the hands of the British navy several years earlier. It had taken more than three years for him to prove that he was an American with valid seaman’s papers and gain his release. Unfortunately for the British who attacked Stonington, during his service in the British Navy, Holmes had become an expert, accurate gunner. Caulkins notes that the defenders were all “self-impelled and self-directed.” Town officials sent messengers to all neighboring towns seeking powder and reinforcements, but an uneasy silence endured for two more hours as the town’s defenders waited for the fighting to begin. The Terror started bombarding the Point at 8 p.m. The defenders fired back with its 18-pounder. Congreve rockets and bombs showered the village, lighting up the night like fireworks. The band of volunteers manned the cannons and used the light of fire from the British ships to aim their returning cannonade. The bombardment continued until midnight.

Though there was no organized effort to fight any fires that first night, enough people dared the shower of bombs and rockets to put out any fires that started. Amazingly, not a single building burned to the ground, according to Caulkins. Also in Caulkins’s manuscript she described the luck of one young man who had promised a widow that he would protect her house from fire and plunder. When the shelling stopped, he fell asleep. Awakened by the renewal of the attack the next morning, he rushed outside. Returning to the house, he discovered a smoking shell had fallen through the roof onto the bed he had occupied. The feather mattresses had smothered it, reports Caulkins, whose description of the battle cites eyewitness and participant recollections.

Accurate news of the attack was hard to come by. On August 10, a New London paper reported, “It is confidently reported that the British fleet have taken possession of the Point and ordered the families who lived there to retire ten miles from the point.” The truth was that on the morning of August 10, Stonington still continued its defense.

At dawn the British again fired on the town. The Dispatch had moved in closer to shore overnight, within half a mile of the coast. Its guns laid down a withering broadside. Caulkins, again citing eyewitness accounts, wrote that it seemed impossible for anyone to survive the British firepower. She claimed that the shells blasted the flag from its pole, shattered the barricade, and tore up dirt around the little fort. Yet the tiny group of defenders stayed at their posts until they ran out of powder. The men rescued their downed flag, spiked their cannon, rendering them inoperable should the British try to capture them, and retreated amidst the taunts of the British Navy carrying across the water: “We want balls; can’t you spare us a few?” The defenders shouted back, “When the powder comes, you shall have enough.” Caulkins, again citing eyewitness accounts, described the retreating men: Many had lost their hats, their clothes were begrimed with powder and dirt, their faces were blackened, and their eyes were burning.

For more than an hour the British fired, unimpeded, on the hapless village. The defenders became a fire crew. At 8 a.m., fresh powder arrived from New London. The original 20 defenders, their number now increased by a half dozen more, returned to the barricade. They nailed their flag back to the flagpole, drilled out the cannon, and set about defending the village. The firing continued between shore and ship, nonstop, for four hours. The volunteers managed to damage the Dispatch severely, hitting it below the water line, damaging the rigging, killing a number of British sailors, and forcing it to withdraw out of their range.

Although this was not the end of the fight, the young defenders celebrated as though they had already won. They shouted in victory; they leapt from stone to stone in the barricade; they climbed on fences and fence posts; they waved their hats in exultation. The flag, shot through seven times by British shells, still waved in defiance over the tiny breastworks.

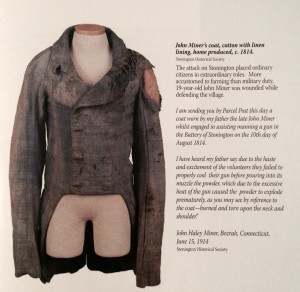

The celebration was short-lived. Survivor Jesse Deane later described helping a fellow defender stagger away from the barricade. The clothes of Frederick Denison, age 19, bore blood from his wounded knee, caused by flying debris from the shattered walls of the breastworks. Denison’s wound seemed minor at first, but infection set in, and just a few months later he died, the only American fatality of the attack. Young John Miner suffered a powder burn to his face and eyes from a premature ignition of one of the cannon. Initially totally blinded, he later recovered the sight in one eye.

Not only did the defenders have to cope with their wounded after their triumph over the Dispatch, but they had to resume fighting as the British returned to the attack. The Ramillies, the largest ship of the attacking squadron, now approached as close as it could to shore and seemed ready to take up the unfinished job of the Dispatch. The Pactolus also drew nearer and anchored. Stonington’s end appeared near.

Hoping to forestall this dreadful outcome, the town magistrates sent two men to meet with Captain Hardy. Under a flag of truce they rowed out to the Pactolus to find out why the British had attacked poor Stonington and to try to save it. Hardy, who had been the commanding officer of Lord Horatio Nelson’s flagship Victory during the Battle of Trafalgar, was said to have welcomed them politely, even pointing out the couch where, he said, “Lord Nelson lay in his death after I had given him my parting embrace.” Hardy then accused the men of Stonington of providing torpedoes that Americans had used against British ships in Long Island Sound and refusing to release the wife of the British vice-consul James Stewart at New London. (See page xx for more on the Stewarts.) The men of Stonington received these charges, according to Caulkins, “with surprise, contempt, and indignation.” They had launched no torpedoes, and they did not have Mrs. Stewart. According to Caulkins’s manuscript, the men of Stonington believed that Hardy had absolutely no reason to believe Mrs. Stewart was in Stonington and was merely using that as a pretext for his assault. Hardy gave the town until 8:00 the next morning to deliver Mrs. Stewart. If it did not, he promised to destroy the town. The men then rowed back to the town to prepare for additional attacks.

Inexplicably, Hardy held his fire the following morning. The town magistrates, under another flag of truce, informed Hardy at 8 a.m. that they could not effect a release of Mrs. Stewart. Hardy extended the ceasefire until noon, saying that if the authorities did not bring Mrs. Stewart on board by then, he would demolish Stonington.

At noon, the British launched the renewed assault with bombs from Terror. She was able to launch her bombs from so far off shore that fire from the cannon at the Stonington battery couldn’t reach her. The defenders again retreated from the protection of the battery walls and served as a fire brigade in the village.

That night the British bombardment stopped, but it began again early on the 12th. Both the Pactolus and Ramillies had worked their way even closer to the Point overnight. According to Caulkins, at 8 a.m. the two ships “opened a cannonade with the design of raking the village and sweeping it, as it were, from the earth.” Fortunately for the village, most of the balls fell short or overshot the town. The firing stopped at noon, and the two ships drew away from the shore. The next morning, the 13th, the British squadron set sail from Stonington without firing another shot, returning to its position at the mouth of the Thames River off New London.

The attack by the British was a horrible assault on the peaceful denizens of Stonington, yet despite hours and days of bombardment, damage to the town was surprisingly light. Haynes claimed that the real reason for the lack of damage was that the British aimed at the Stonington Congregational Church steeple near the current Wadawanuck Square, believing it marked the center of the village. In fact, he wrote, the majority of the Borough’s 100 houses actually were clustered near the barricade near the Point, with the result that most of the British shells landed harmlessly in fields beyond the town center.

Nevertheless, Caulkins reported, the British assault damaged about 40 buildings but none beyond repair. On the Stonington side casualties were also surprisingly light. Aside from the wounds suffered by young Denison and Miner, four other defenders had minor injuries. Residents lost a horse and one or two other farm animals, but the total damage amounted to only about $3,500.

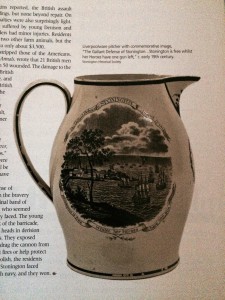

Liverpoolware pitcher with commemorative image, “The Gallant Defense of Stonington…”, c. early 19th century. Stonington Historical Society

British losses far outstripped those of the Americans. Caulkins, citing Holmes’s Annals, wrote that 21 British men were killed and more than 50 wounded. The damage to the Dispatch and some of the British landing barges was severe, and the report estimated the British used 50 tons of metal in the bombs, rockets, and shells they fired at the town. For many years after the assault, one Stonington home-owner adorned his gatepost with remnants of a large shell. Inscribed on the shell were the words: “Bomb-ship Terror, Aug. 10th, 1814, W. 215 lbs.” Etched on the other side were the words, “Stonington will be defended while its heroes have one cannon ball.”

Chroniclers of the defense of Stonington have focused on the bravery and recklessness of the original band of defenders, mostly teenagers who seemed oblivious to the dangers they faced. The young men leapt from rock to rock of the barricade, waving their hats over their heads in derision and defiance of the attackers. They exposed themselves to British fire to drag the cannon from place to place and to put out fires or help protect property. Yet foolhardy or foolish, the residents of the little coastal village of Stonington faced down the might of the British Navy, and they won.

Nancy Steenburg is an adjunct professor of history and the director of the Continuing Education office at the Avery Point campus of the University of Connecticut. She is the author of the 2005 Children and the Criminal Law in Connecticut: 1635-1855.

Explore!

Read all of our stories about Connecticut in the War of 1812 in our Summer 2012 issue

Read all of our stories about Connecticut at War on our TOPICS page