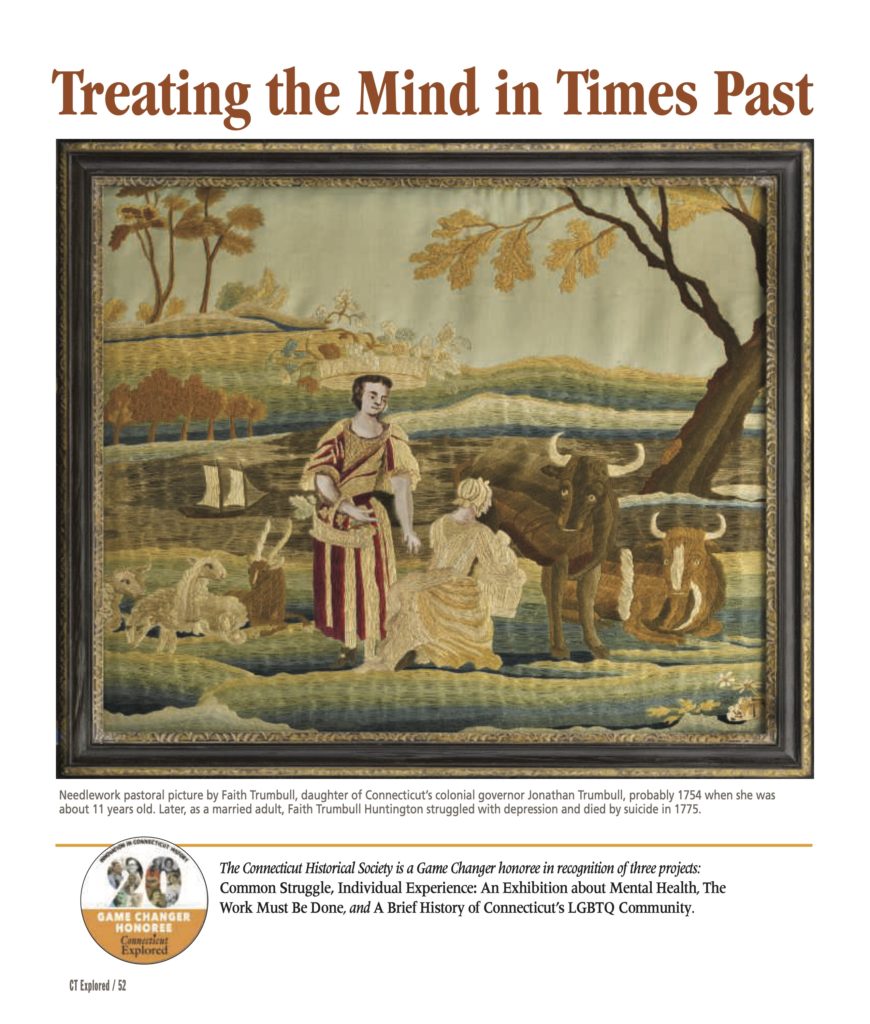

Needlework pastoral picture by Faith Trumbull, daughter of Connecticut’s colonial governor Jonathan Trumbull, probably 1754 when she was about 11 years old. Later, as a married adult, Faith Trumbull Huntington struggled with depression and died by suicide in 1775. Connecticut Historical Society

By Ben Gammell

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc., Fall 2022

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

On January 13, 1771, Mary Fish Noyes, a 34-year-old widow and mother, wrote in her diary about the weather. “So stormy I could not go out and had a comfortable day in my mind but in the evening my burden returned. O when will it please the lord to set me free!” Of course, she wasn’t writing only about the weather. Between 1770 and 1771, following the death of her young daughter, Noyes struggled with “melancholy,” which we might today call depression. During this time Noyes moved with her two sons from New Haven to her parents’ home in Stonington, where she kept a “spiritual diary,” as Julius Rubin, in Religious Melancholy and Protestant Experience in America (Oxford University Press, 1994), called it, a firsthand account of her “inward journey from despair to rekindled faith and health.”

Although 251 years and an 18th-century religious and colonial worldview stand between Noyes’s experience and today, her diary entry feels familiar. With a few different word choices, someone in 2022 might write the same thing—or email or tweet: “Today was rainy and I stayed in, I felt OK. Tonight was tough. Oh God, will this ever end?” Our understanding of mental health and illness—and how to maintain or treat it—has changed, though, and continues to change over time. Noyes’s melancholy appears to have been temporary, perhaps a period in life dominated by grief that passed or was helped by religious faith and practice or some other unknown factor. Time, prayer, medication, and therapy (in different forms) are among the sources of mental health treatment sought by people in the past as well as today. This continuity—mental health challenges faced by those in different times and places—is at the center of the Connecticut Historical Society’s (CHS) Common Struggle, Individual Experience: An Exhibition about Mental Health, on view through October 16.

With documents, images, and artifacts from the CHS collection and from other lenders, this exhibition explores important milestones in the history of mental health treatment in Connecticut, such as the founding of the Connecticut Retreat for the Insane in 1822, one of the first hospitals of its kind in the United States and known today as the Institute of Living. Other significant events include the 1868 opening of Connecticut’s first state mental institution, the Connecticut Hospital for the Insane in Middletown (now Connecticut Valley Hospital). Mental healthcare reformer Clifford Beers exposed mistreatment at these institutions and founded the National Committee for Mental Hygiene in 1909 (now Mental Health America) and the Clifford Beers Clinic in New Haven in 1913, the first outpatient mental health clinic in the United States.

But the primary structure, flow, and content of the exhibition focuses on the personal experiences of those with mental health challenges. These stories appear in letters, photographs, medical records, and books reaching back to the 1700s and in contemporary interviews with Connecticans who shared their struggles with and perspectives on mental health with the CHS during the winter of 2020 – 2021. Mary Fish Noyes wrote in her diary about her stormy day in 1771. Clifford Beers wrote in his 1908 book A Mind That Found Itself, “Until some one tells just such a story as mine and tells it sanely, needless abuse of helpless thousands will continue.” And Terese Mayer, in a 2021 interview with the CHS, shares, “I can hide it really well. From the outside it may appear that I’m functioning great, but I could be falling apart inside.”

The CHS interviewed 21 people, and excerpts from these interviews appear on video kiosks throughout the exhibition. The diversity of participants and viewpoints helps convey the topic’s complexity and relevance. Kathy Flaherty is the executive director of Connecticut Legal Rights Project, an agency in Middletown that provides legal services to low-income individuals with mental health conditions. She served on the exhibition’s advisory board and shared her own struggles in an interview. The interviews are personal and moving, and they reflect the feeling of many of the interviewees that conversations about mental health should be commonplace. “A lot of times,” said Flaherty, “I think the biggest challenge is that people shy away from difficult conversations because we don’t like to see anybody in pain. We don’t like to be in pain ourselves, but we don’t like seeing that in somebody that we love. But if we don’t talk about it, if we keep it hidden, nothing good comes from that.”

To present mental health-related stories from the past, the CHS exhibitions team looked for evidence in the museum’s collection. Some stories are well documented, such as that of Faith Trumbull Huntington, daughter of Connecticut’s colonial governor Jonathan Trumbull. Huntington struggled with depression and died by suicide in 1775. Letters between Huntington and family members, including her parents, brothers, and husband Jedidiah, reveal an extended family’s witnessing the mental and physical deterioration of a loved one as they do everything they can, within the understanding of depression at the time, to provide help, including hiring professional care. Despite the loving attention of her family, their attempts at home remedies such as travel and socializing, and the assurances and medicinal prescriptions of top doctors, Huntington wrote of “Some Anxiety I Can’t Shake [off]” and eventually hanged herself following a family Thanksgiving celebration. The family letters and several framed needlework pieces by Huntington (a talented needlework artist) are preserved in the CHS collection, including some on view in the exhibition.

Common Struggle, Individual Experience: An Exhibition about Mental Health on view at the Connecticut Historical Society, Hartford, 2022.

These are valuable records of personal struggles with mental health, which are not always easily found in historical archives. Official medical records are more likely to be preserved, and several 19th-century documents from the Retreat for the Insane, such as a physician’s report listing patients’ diagnoses and their causes, are on view in the exhibition. But access to medical records can be restricted. Evidence of personal struggles with mental health in the past are often fragments of a story.

Sometimes a single letter in a collection of papers opens a window into a person’s struggle. In a letter written in 1847 by Cemanthia Horn (hometown unknown) to a relative named John Pierce in Massachusetts, Horn describes the exhausting and isolating experience of caring for her children while witnessing her husband William lose his battle with an unknown mental health condition. In the winter of 1846 – 1847, Horn trekked through the woods in a foot of snow to find her husband in a tree, alive, but with a rope around his neck. She pleaded and convinced him to come back home. Four weeks later Horn “went away a little while,” leaving a 14-year-old boy to watch William. When she returned, William had hanged himself in the house. Horn wrote, “It don’t seem as though he was dead, but it is reality. There is no one knows or realizes the loss of a near and dear husband or companion but them that has the trial of it, but the poor creature is dead, he was an unhappy creature for three months before he died. His making way with himself was nothing more than what I expected, but still I did not realize that he would do it until he did it. But oh, the lonesome days and hours that I had when he was in that situation. There was scarce a person that came into the house during the time he was in that situation. It seemed to me that I was forsaken entirely, I was all alone with my children most of the time.”

Cemanthia Horn’s experience may be similar to that of many caregivers who, unlike the wealthy Trumbull family, had few resources and tried to care for loved ones on their own. Throughout history, even with the establishment of asylums and hospitals, most people struggling with their mental health were cared for at home by family members. After her husband’s death, it appears that Horn moved in with her father and took in boarders to “pay my way and take care of my children.” But “I am so tired of living so,” she writes, “I am so discontented, if I could have a home of my own where I could get settled down I would not care how hard I had to work, I would be content.” (The spelling in this letter has been modernized for clarity.)

Another letter in the CHS collection offers a narrow but nonetheless shocking window into professional treatment in the 1830s. In 1839, not long after the opening of the Connecticut Retreat for the Insane (a privately-run institution), a commission began investigating the need for a state-run facility (the eventual Connecticut Hospital for the Insane) and administered a survey to town physicians to evaluate the number of people in need of professional mental health treatment. In response to this survey, Voluntown selectman Dr. Harvey Campbell wrote about 53-year-old Patrick Bentum, an impoverished Black man who had been “insane” for 20 years and had been “chained and handcuffed for the first 3-4 years” before Campbell took charge of him.

Campbell documented his treatment. To control Bentum, Campbell “bled him frequently as punishment, and often too applied the rawhide.” Bloodletting remained a medical treatment for many ailments into the late 1800s. Dr. Benjamin Rush (1746-1813) believed “madness to be a disease of the blood-vessels of the brain” and prescribed bloodletting, purging, and recreation. Of course, in this case Campbell’s bloodletting can’t be excused simply as medical treatment. According to Campbell, Bentum could not afford the hypothetical two dollar weekly fee at an institution, and neither Campbell nor the town offered to pay. Besides a brief mention of Bentum’s sister, Mary, whom Campbell described as a mild case who could support herself, the story ends there. Patrick’s and Mary’s voices are unheard.

Bentum’s and other stories in Common Struggle, Individual Experience point to recurring themes in the history of mental health: the need for more funding and access to treatment (including beds and facilities for patients), barriers to treatment such as racism and poverty, the need for compassion and empathy, the reality that mental health challenges are all around us and always have been, and the importance of simply talking about it.

James Scott is a retired Connecticut State Police officer, Army National Guard veteran, and current faculty member at Albertus Magnus College in New Haven. In 2016 Scott was involved in a legally-justified police shooting and sought professional mental health treatment to help him process the aftermath of that event. In his interview with the CHS for this exhibition, Scott described his initial embarrassment at seeking help and how he visited a therapist out of state in order to avoid being recognized. His message for police colleagues and first responders reflects a broader message found throughout the exhibition, a message of hope for our ongoing and future understanding of mental health. “For any officer or first responder that’s struggling, I would remind them that there’s a lot of people that care about you. There’s people that love you, that you need to be there for. It’s okay to ask for help. And that’s why I expose myself and tell my story. I go all over the country telling this story. I’m not ashamed. There was a time where I couldn’t tell my story without a full box of Kleenex, and I might not get through the whole story, but the more I tell it, the easier it gets. And if I could help one person, that’s great.”

Common Struggle, Individual Experience: An Exhibition about Mental Health, presented by Hartford HealthCare Institute of Living, is on view at the Connecticut Historical Society through October 16, 2022. For a virtual tour of the exhibition visit chs.org/exhibition/common-struggle-individual-experience/.

Please note that nothing in this article or in the CHS exhibition is intended to diagnose the mental health condition of a person from the past or present.

Ben Gammell is director of exhibitions for Connecticut Historical Society. He last wrote “Obey Your Air Raid Warden,” Fall 2020.

The Work Must Be Done

The Work Must Be Done, a collaborative project between Dr. Brittney Yancy, assistant professor of humanities at Goodwin University, and the Connecticut Historical Society, raises up the stories of the women of color who participated in the fight for voting rights. [See “Uncovering African American Women’s Fight for Suffrage,” Summer 2020.]

The project title draws upon the words and inspiration of leading suffrage and labor rights activist Mary Townsend Seymour of Hartford. Many women of color advocated for voting rights and valued their electoral voices. They worked to protect and uplift communities of color. Annie Drury, for instance, led the Anti-Lynching Crusaders in Norwich, and Minnie L. Bradley of New Haven was a founder of the National Association of Wage Earners, a political organization for Black women workers’ rights.

The research team included Dr. Yancy, CHS Chief Curator Ilene Frank, CHS Research Historian Dr. Karen Li Miller, and assistants Chelsea Echevarria and Chianna Calafiore. They worked to uncover the names and stories of women across Connecticut, including those in Bridgeport, Norwich, New Haven, and Hartford who were involved in the fight for the right to vote.

The Work Must Be Done is a public humanities project with multiple components, including public presentations, a website, and traveling banners that are available to borrow by reservation. The project was supported by Connecticut Humanities and the League of Women Voters of Connecticut.

For more information visit research.chs.org/women-of-color-suffrage.

A Brief History of Connecticut’s LGBTQ Community

A Brief History of Connecticut’s LGBTQ Community is a traveling exhibition and online digital timeline created by the Connecticut Historical Society and Central Connecticut State University. In 2019 the CHS partnered with CCSU Assistant Professor of History William Mann, CCSU students Anna Fossi and Eve Galanis, and additional students in Professor Mann’s history class. Building upon the work of LGBTQ activist and researcher Richard Nelson, the team explored the university’s extensive archive related to gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgender history. Using additional primary sources from the CHS collection, they produced eight traveling banners that reveal how Connecticut’s LGBTQ population has moved from leading hidden, often solitary lives to claiming visible, powerful, valuable, and contributing places in society. The banners include stories about 19th-century same-sex relationships, 20th-century safe gathering spaces such as the Cedar Brook Café in Westport, and legislative fights and victories such as Connecticut’s 1991 gay rights bill. The banners are available to libraries, universities, museums, and other venues for a rental fee. In addition, the digital timeline on the CHS website includes and expands upon the historical content from the banners, and continues to grow. Visitors to the website are encouraged to submit additional images and events in Connecticut’s LGBTQ history to CHS.

For more information visit chs.org/lgbtq. William Mann wrote “A Brief History of Connecticut Gay Media,” Winter 2020-2021, and spoke to us for Grating the Nutmeg Episode 119, “Uncovering Connecticut’s LGBTQ History.”

Explore!

See all of our 20 for 20: Innovation in Connecticut History Game Changers

GO TO NEXT STORY

GO BACK TO FALL 2022 CONTENTS