by Ruth Glasser (c) Connecticut Explored, Fall 2002

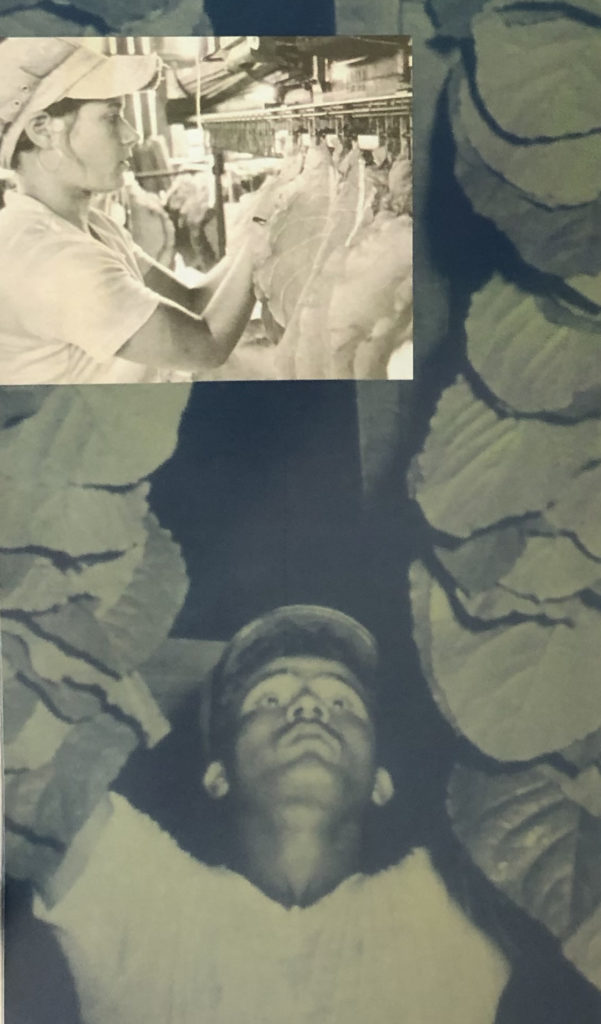

Inset: Sonye Davis sews tobacco leaves, Windsor, 1975. photo: N. Roy, The Hartford Times archives, Hartford History Center, Hartford Public Library

“If there’s a harvest, you’ve got Puerto Ricans working there,” observes Néstor Morales. Morales knows what he’s talking about-he first came to Connecticut from his native Cataño to work on a tobacco farm.

It was 1964. Morales was a veteran of the United States Army. He was a trained cook, but unemployment was high in Puerto Rico and he couldn’t find a job. So he went to his regional employment office in Bayamón and filled out an application to be a farm worker on the United States mainland.

Morales didn’t know where he would be going until he was on the plane. “It could be Florida, it could be Chicago, it could be New Jersey. I wound up in Connecticut.” But he and his companions were so desperate that, “We didn’t care where they sent us. We just wanted to work.”

In late April, Morales and his fellow recruits arrived at the Hartford/Windsor Locks airport. Buses took them to a camp surrounded by barbed wire and patrolled by armed guards. From there, the workers were sent to different tobacco farms in northern Connecticut and southern Massachusetts.(1)

Néstor Morales was just one of tens of thousands of Puerto Rican farm workers who came to Connecticut in the post-World War II era. Why did Morales and so many others feel a desperation that made them leave their homes, families, and friends behind in Puerto Rico? What was it like to be an agricultural contract worker in Connecticut?

Agricultural Upheavals

Before the Spanish-American War of 1898, most Puerto Ricans were struggling small farmers or plantation workers. The defeat of the Spanish and the beginning of United States occupation of Puerto Rico only made their situation worse. Puerto Rico’s coffee farmers were not protected by United States tariff laws and could not compete in the world market against other coffee producers. When Hurricane San Ciriaco hit the island in 1899, it destroyed that year’s crop and put many farmers over the edge financially.

| En términos de quienes venían a las fincas, el emigrante de los años 40 era un hombre más avanzado en edad que tenía mucha experienca en el cultivo. Y eran más propensos a ir y venir. Al envejecer, menos de ellos venían, y eran reemplazados por hombres más jóvenes, quienes frecuentemente buscaban viviendas y asentamiento en el área. Pienso también que las mujeres comienzan a llegar a partir de los años 70. Antes de eso la inmensa mayoría eran hombres.

In terms of who was coming to the farms, the migrant of the 40s was an older man who had a great deal of experience in farming. And they were more likely to go back and forth. As they got older, fewer of them came, and they were replaced by the younger men, and it was the younger men very often who then sought housing and settling into the area. I think also that in the 70s you have women coming. Prior to that it was overwhelmingly men. JULIO MORALES |

In the meantime, the island’s huge sugar industry was increasingly controlled by United States companies. During the first half of the 20th century, United States sugar plantations swallowed up many acres of land formerly belonging to small farmers. As these big growers used more sophisticated machinery to cultivate, harvest, and process the sugar, they also hired fewer and fewer workers. Small farmers and plantation workers displaced by the decline of coffee production and the corporatization of the sugar industry poured into Puerto Rico’s cities.

Industrialization & Migration

Operation Bootstrap was a post-World War II economic development program formulated by the Puerto Rican government. It attracted manufacturing concerns, mainly from the United States, with the promise of land, tax breaks, and cheap labor. But the companies coming to Puerto Rico did not provide nearly enough jobs. Even Puerto Rican government officials admitted that Operation Bootstrap could not alleviate unemployment unless as many as 60,000 people left the island each year.(2)

There was a strong precedent for such a migration. In the early part of the 20th century, Puerto Ricans had worked in agriculture and industry in places as far flung as Ecuador, Hawaii, Venezuela, and Arizona. Since becoming United States citizens in 1917, many had come to the mainland in search of jobs. Most settled in New York City. By 1947, the New York daily press sounded an alarm over the tens of thousands of Puerto Ricans flowing into the city. They claimed that there would not be enough jobs and social services to accommodate the migrants.

In the meantime, large-scale United States farmers were looking for workers. Since the 19th century, they had benefited from an almost unrestricted flow of overseas labor to work their low wage, undesirable jobs. But beginning in the 1920s, a series of federal laws severely limited the number of immigrants into the United States. By the post-World War II era, there were few United States residents willing to labor in agriculture.

It was not surprising, therefore, that both island and mainland government officials would see Puerto Ricans as a solution to the labor needs of United States growers. In 1947, the Department of Labor of Puerto Rico established its Migration Division to arrange contracts between mainland farmers and unemployed Puerto Ricans. Division recruiters traveled the winding island roads in cars with bullhorns, distributed leaflets, and placed ads in newspapers announcing good jobs in the United States. By 1955, the Migration Division had also established offices in Pennsylvania, New York, New Jersey, Massachusetts, Ohio-and Hartford, Connecticut.

| Llegamos a Connecticut (en 1958) porque mi padre fue contratado como capellán para los trabajadores migrantes por el Greater Hartford Council of Churches (Concilio de Iglesias de la Región de Hartford). Cuando mi padre iba a los campamentos, llevaba la familia entera, a nosotros cinco, porque los hombres estaban tan aislados y esos campamentos eran tan estériles, eran horribles. No tenían a donde ir, no tenían carros, imagínate, un campamento de tabaco en Windsor, ahí no hay nada que hacer.

We came to Connecticut (in 1958) because my father was hired as a chaplain for the migrant workers by the Greater Hartford Council of Churches. When my dad went to the camps, he would take the whole family, the five of us, because the men were so lonely and the camps were so barren, they were awful. They had nowhere to go, they had no cars, I mean a Windsor tobacco camp, there’s nothing to do. EDNA NEGRóN |

Thus, in 1948, 4,906 Puerto Ricans came to the United States to work under contracts with the Puerto Rican Department of Labor. By 1968, 22,902 workers came to 14 states, mostly on the East Coast. By the mid-1960s, 25% of these workers went to Connecticut, second only to New Jersey at 45%. Tens of thousands of other workers came through illegal private contracts or with no contract at all.(3)

Most of the Connecticut-bound were hired by local growers to work from spring to fall. This extended season coincided with the tiempo muerto, or “dead time,” of the sugar industry, enabling migrants to work half a year on U.S. mainland farms and then return to the island to labor in cane fields or sugar mills.

Puerto Rican farm workers labored in many parts of Connecticut. They pruned trees and watered plants in nurseries in Meriden, weeded tomatoes in Cheshire, and picked mushrooms near Willimantic. Most, however, came to work tobacco in the Connecticut River Valley. The region, known as “Tobacco Valley,” once extended from Hartford, Connecticut, to Springfield, Massachusetts, covering an area 30 miles wide and 90 miles long. Changes in tobacco growing at the end of the 19th century had created a great demand for workers. In 1899, one year after United States troops stepped onto Puerto Rican soil, the same year that Hurricane San Ciriaco devastated the island’s coffee crop, Connecticut farmers were experimenting with new ways of cultivating tobacco. For centuries, the rich soil of their valley had produced a good crop. Now tobacco farmers tried to duplicate tropical conditions by growing their plants under white netting. This process shielded plants from direct sunlight, created a humid atmosphere, and produced high quality leaves. After an elaborate cutting, sorting, and curing process that took several years, these “shade tobacco” leaves were then used to wrap the most expensive cigars.

A group of men and women workers riding behind a tractor, July 1967. photo: Ellery Kingston, The Hartford Times archives, Hartford History Center, Hartford Public Library

Chronic shortages of labor plagued Connecticut’s tobacco industry. During the early part of the 20th century, growers employed many Polish, Lithuanian, and Italian immigrants. But post-World War I immigration restrictions and the lure of factory jobs depleted that workforce. The growers began to recruit African-American college students from the South. Among those coming in 1944, in fact, was the young Martin Luther King, Jr. During World War II, this student labor force was joined by thousands of Jamaican contract workers.(4)

While the peak years for Connecticut shade tobacco cultivation were in the 1920s, close to 200 farms were still growing it in the post-World War II era.(5) Three giant companies and several smaller ones made up the Shade Tobacco Growers Association. The Association petitioned the Puerto Rican Department of Labor for workers who were “strong in physical stature, in good health, free from communicable diseases, accustomed to hard work.”(6)

As the growers’ request for laborers implied, the work was strenuous. Tobacco plants and leaves were fragile and had to be handled carefully. Moreover, both the tenting process and the curing of leaves in heated sheds made the work unbearably hot and humid. A high level of stress and accidents resulted from the constant pressure to work faster. Although the growers were supposed to abide by a Puerto Rican Department of Labor contract that was renegotiated every year, they often violated contract terms. The 1969 contract, for example, said that the workers were to be paid at least $1.60 per hour for work in the fields and warehouses of the tobacco companies. They would work 40 hours per week, with time-and-a-half pay for overtime. The contract required three “adequate” daily meals at a cost of $2.20 per day.(7)

In reality, however, a farm worker’s day of labor might be 10 to 14 hours, 6 or even 7 days a week, with no overtime pay. Moreover, exorbitant deductions for plane fare from Puerto Rico (to be reimbursed only if the workers completed their contracts), meals, health care, and other expenses whittled down already modest wages by as much as two-thirds.

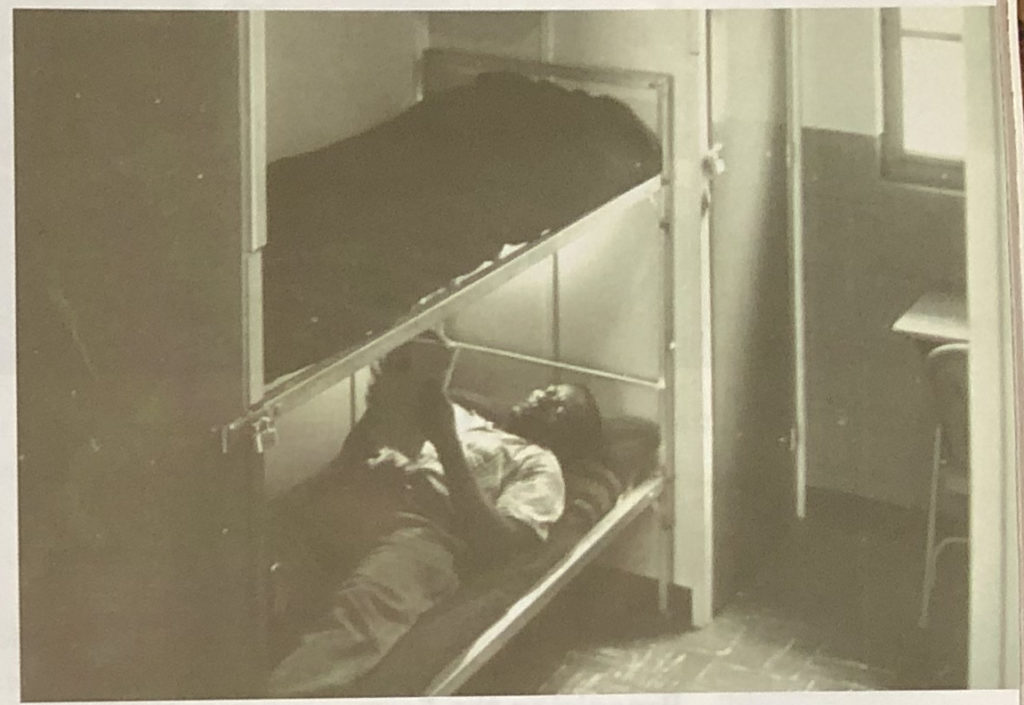

| Los que vivían en la finca propiamente, vivían en condiciones pésimas. Eran como unas barracas y allí pues, habían doce o catorce hombres en unos catres uno encima del otro. No había calefacción, a veces no había agua potable.

Those who lived on the farm lived in the most horrible conditions. There were like barracks with 12 or 14 men in cots that were on top of one another. There was no heat, sometimes there was no drinkable water. José La Luz |

Accommodations usually consisted of large barns or barracks where as many as 50 or 60 men slept on flimsy cots. In the still-cold nights of April or the growing chill of October, the workers frequently suffered from lack of heat and adequate blankets. Plumbing and sanitation were often rudimentary at best.

Workers who protested such conditions were labeled “troublemakers,” unceremoniously ejected from their camps, with no money, food, or way to get to the nearest town. While some accepted the situation with resignation, many workers’ anger over their treatment was intense, based not only on Connecticut conditions but also on prior experiences in Puerto Rico. Tobacco had been cultivated for centuries in Puerto Rico’s own version of Tobacco Valley, an area flanked by the east-central towns of Comerío, Caguas, and Cayey. While most tobacco growers were Puerto Rican small farmers, after 1898 cigar production was dominated by United States companies. Many of Connecticut’s Puerto Rican tobacco workers came from those areas and had worked for companies such as General Cigar and Consolidated Cigar, two of Connecticut’s giants. Maintaining strictly anti-union and low wage policies in their Puerto Rican fields and processing plants, these companies earned huge profits and paid no corporate tax.

The ties between the tobacco giants and Puerto Rico may have had something to do with the Migration Division’s apparent inability or unwillingness to enforce contract provisions. Officials likely feared that if the cigar manufacturers were pressured, they would both close their operations on the island and stop bringing migrant workers to Connecticut.

Organizing the Farm Workers

In the absence of government protection, other groups stepped in to help the farm workers. Several coalitions of church, union, and political groups formed to improve camp and work conditions. CAMP, the Comité de Apoyo al Migrante Puertorriqueño (Puerto Rican Migrant Support Committee), formed in Puerto Rico in 1969 by the Industrial Mission of the Episcopal Church. By the early 1970s, Connecticut’s farm worker advocates included a spectrum of local churches, the Young Lords (a radical Puerto Rican youth group inspired by the Black Panthers), the Puerto Rican Socialist Party of Connecticut, and Legal Services lawyers from around the state.

A tobacco worker reading in his bunk, Windsor Farms Supply, no date. The Hartford Times archives, Hartford History Center, Hartford Public Library

In 1972, META, the Ministerio Ecuménico de Trabajadores Agrícolas (Ecumenical Ministry of Agricultural Workers), replaced CAMP. In August of 1973, some 100 Puerto Rican workers gathered outside of Camp Windsor and declared the formation of a union, ATA, the Asociación de Trabajadores Agrícolas (Agricultural Workers Association).(9) These organizations challenged the law giving Puerto Rico’s Secretary of Labor sole authority to negotiate with the growers on behalf of the workers and filed lawsuits against the government of Puerto Rico and the Tobacco Growers’ Association. META and ATA claimed that the yearly contract bargaining sessions between government and the growers were really “sweetheart” negotiations, that there was a “conflict of interest in [the government]negotiating contracts with the same firms they seek to attract to the Island.”(10)

Since access to the tobacco camps was restricted, organizers contacted the “day haulers” who lived in Hartford or visited workers back in Puerto Rico during the winter months. Churches gave spiritual help to the migrants, took their complaints to farm managers and tried to educate the general public about the problems on the farms. Farm workers and their allies advocated for better living conditions and health care, increased wages, sick and overtime pay, and unrestricted outsider access to the camps, threatening strikes and boycotts if their stipulations were not met.

The growers were, of course, infuriated by these activities. But the more they tried to suppress worker protest, the more it emerged. Throughout 1973, hundreds of Puerto Rican tobacco workers struck over poor food and the firing of co-workers involved in earlier actions. A Good Friday celebration in Windsor Locks, led by visiting clergy, turned into a demonstration. Later that year, growers had a minister and a nun arrested for entering Camp Windsor without permission. In turn, META filed a suit on behalf of these arrested spiritual leaders.

ATA’s and META’s attempts to get a farm workers’ rights bill passed in the Connecticut General Assembly met with frustration. The powerful Tobacco Growers Association and other farmer groups successfully lobbied against it, insisting on an anti-strike clause and threatening to close down their operations.

The Connecticut farm workers’ movement was given a boost, however, when United Farm Workers (UFW) founder César Chávez came to the state in the summer of 1974, fresh from his triumphs organizing grape and lettuce workers in California. Meeting with clergy and Puerto Rican activists throughout Connecticut, he gave his blessing and some funds to the tobacco workers’ struggle. ATA decided in 1975 to affiliate with the UFW, but that union’s own pressing financial and organizational needs in the West prevented it from working effectively in the Northeast. Without that critical UFW support, the movement for unionization of Connecticut’s Puerto Rican agricultural workers faded away.

Nevertheless, all the newspaper articles, protests, and court cases had focused a great deal of attention on the situation of Puerto Rican farm workers in Connecticut. META and ATA had successfully sued the Shade Tobacco Growers Association for the right to freely enter the workers’ camps. The Connecticut Labor Council, along with the United Auto Workers and many unions in Puerto Rico, had declared their support for the farm workers’ right to organize. The Puerto Rican Department of Labor, while still not recognizing ATA, had agreed to stop using misleading radio ads that enticed workers from Puerto Rico, to revise the contracts and to add more staff to deal with farm worker complaints. Embarrassed by charges that they were not protecting their own workers, the Department drastically shrank the agricultural contract program. In 1974, 12,760 workers came through the program, but the following year it was down to 5,639. By 1984, there were only 1,954 participants.(11) Many farmers also found that it was now easier and cheaper to get some of their tasks done by machines-or move production overseas-than to deal with a workforce that demanded better wages and treatment. Others increased the numbers of “day haul” workers, often students or Puerto Rican men and women who lived in nearby towns.

Many Puerto Rican farm workers decided to improve their conditions by “voting with their feet.” They left the fields and found factory jobs in the nearest cities. Just as surely as they had planted and tended the crops in Tobacco Valley, Puerto Rican farm workers began to put down their own roots in Hartford and other cities throughout Connecticut. Together, with other Puerto Rican migrants who had come to labor in factories, these former agricultural workers helped form the nuclei of entirely new communities. This aspect of their history is but one thread in the varied and lively tapestry of Puerto Rican experiences that is Connecticut’s legacy.

1 Interview by author, December 12, 1991.

2 Luis Nieves Falcón, El emigrante puertorriqueño (Río Piedras, Puerto Rico: Editorial Edil, 1975), 15.

3 History Task Force, Center for Puerto Rican Studies, Labor Migration Under Capitalism (New York: Monthly Review Press, 1979), 244; Michael Lapp, “Managing Migration: The Migration Division of Puerto Rico and Puerto Ricans in New York City, 1948-1968.” Ph.D. Dissertation, Johns Hopkins University, 1990, p.185.

4 Richard Arthur Newfield, “Tobacco and the Tobacco Laborer in the Connecticut Valley.” Senior Research Thesis, Department of Industry, Wharton School of Finance and Commerce, 1936, pp.13-15; “Shaping Character: Martin Luther King Jr.’s Tobacco Summer, Connecticut,” August 2000, p.144; Fay Clarke Johnson, Soldiers of the Soil (New York: Vantage Press, 1995).

5 Glenn Collins, “The Perfect Place to Make a Good Cigar,” New York Times, August 13, 1995.

6 Labor contract, December 20, 1969. Archives of the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico, Center for Puerto Rican Studies, New York City.

7 Dan Gottlieb, “Puerto Ricans Come by Air to Harvest Tobacco Crops,” Hartford Times, September 13, 1958.

8 Guillermo Segarra, Letter to Editor, Claridad, July 15, 1972.

9 James Nash, “Migrant Farmworkers in Massachusetts: A Report with Recommendations,” Massachusetts Council of Churches, Strategy and Action Commission, March 1974, p.65.

10 “Agricultural Workers Association,” flyer, n.p., n.d.

11 Lapp, “Managing Migration,” p.184.

Ruth Glasser’s book Aqui Me Quedo: Puerto Ricans in Connecticut/Los Puertorriqueños en Connecticut can be purchased from the Connecticut Humanities Council for $19.95 plus tax. Order by phone 860-685-2260.

All photographs from the Hartford Times Archive, located in the Hartford Collection at the Hartford Public Library.