Thomas J. Dodd during questioning, Nuremberg Trials, 1945 – 1946.Archives & Special Collections, Thomas J. Dodd Research Center, University of Connecticut Libraries

All images courtesy of Archives & Special Collections, Thomas J. Dodd Research Center, University of Connecticut Libraries.

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Fall 2020

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

My Father’s Legacy

By Christopher Dodd

This year marks the 75th anniversary of one of the most important achievements in the history of the United States, and indeed the world: the triumph of justice and the rule of law over the desire for vengeance. I am talking, of course, about the Nuremberg War Tribunal that brought the atrocities of the Holocaust to light, and the men who brought those who committed those atrocities to justice following the end of World War II.

This was an incredible achievement for mankind. As Supreme Court Justice Robert Jackson said at the outset of the trial, “That four great nations, flushed with victory and stung with injury stay the hand of vengeance and voluntarily submit their captive enemies to the judgement of the law is one of the most significant tributes that Power has ever paid to Reason.” As a son of Thomas J. Dodd, this moment in human history has particular significance to me and my family. As a young, 38-year-old lawyer, my father was asked to stand up and serve his country as a prosecutor with a solemn obligation to the victims and survivors of the Nazi atrocities to ensure that justice prevailed over inhumanity.

In the summer of 1945 my father left my mother, myself, and my four brothers and sisters to spend 15 months in Nuremberg, Germany working to bring some of the worst criminals in history to justice because, as he would write to my mother, “sometimes a man knows his duty, his responsibility so clearly, so surely he cannot hesitate—he does not refuse it. Even great pain and other sacrifices seem unimportant in such a situation. The pain is no less for this knowledge—but the pain has a purpose at least.” He also believed that being a part of this trial was “the highest calling of the legal profession,” and that throughout the rest of his career “nothing will ever be really as important” as what he sought to accomplish at Nuremberg.

The Nuremberg Tribunal was a seminal moment in my father’s life, shaping the rest of his career in the U.S. House of Representatives and as a United States Senator. But, on a far more personal level, Nuremberg and my father’s role in it played an important role in my life as well—as a legislator and public servant.

Growing up in Connecticut, I knew far more about the tragic events of the Holocaust than most people of my generation. In those days, the Holocaust still wasn’t widely talked about. But my father wanted his six children to learn and to never forget. Night after night, gathered around our dining room table for dinner, my father would share stories about his 15 months at Nuremberg. He would talk about the rule of law, constitutional and human rights, and about the responsibilities of every citizen to speak up and take action to ensure these types of crimes are never again wrought upon the world. Those discussions around our dining room table were an amazing education, filled with lessons that have guided me throughout my years in the U.S. Congress, working on the Senate Foreign Relations Committee to promote peace and human rights throughout the world while fighting to ensure the protection of the rule of law here at home.

Over the years my family and I have sought to continue my father’s legacy and the legacy of Nuremberg in various ways. With the help of President Bill Clinton and Nobel Peace Prize Winner Elie Wiesel we opened the Thomas J. Dodd Research Center on the UConn campus in 1995 to study and promote human rights around the globe.

Christopher Dodd was U. S. Senator (CT, 1981 – 2011) and is a member of the Thomas J. Dodd Research Center Advisory Board.

top: Nuremberg Palace of Justice, International Military Tribunal at Nuremberg, 1945 – 1946. Archives & Special Collections, Thomas J. Dodd Research Center, University of Connecticut Libraries

Catapulted to the Center of the Nuremberg Trials

By Owen Doremus and Betsy Pittman

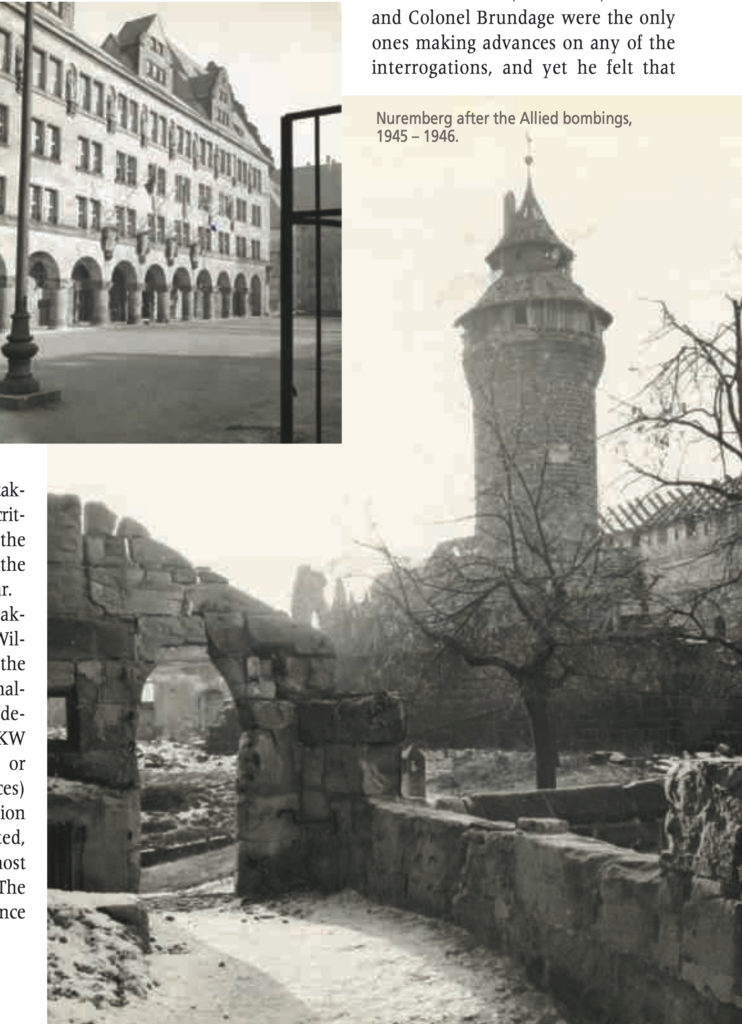

In mid-August 1945 Thomas J. Dodd, a Connecticut lawyer on the staff of the FBI, arrived “in the dead city of Nürnberg [Nuremberg],” as he wrote in a letter to his wife Grace Dodd on August 14, 1945. “I saw for the first time in my life the awful ruin that comes with war. This city is devastated—the buildings, houses and streets are a complete mess. Streetcars piled up, a mass of burned and twisted steel, the rubble is everywhere. Soldiers in helmets and armed on patrol. Nothing but army vehicles on the roads and streets….” Dodd had been selected by Justice Robert Jackson, the lead prosecutor for the United States, to participate in the herculean task of collecting and sorting through the available documentation and to begin formulating the U.S. team’s legal plan to try the remaining major German leaders for their actions both before and during World War II.

Dodd was housed in Hitler’s own Grand Hotel. Severely damaged, the hotel was missing most of the glass in the windows, the walls and floors were compromised and made passable with planking, and the building had no hot water or heat and yet, he wrote, “this is the best in this city that was once home to 400,000 people.”

After settling in as much as was possible, Dodd began the interrogation of prisoners who had been transferred to the city for the coming trial. Between August 14 and August 27, Dodd deposed Alfred Rosenberg (minister of culture and occupied countries), Field Marshall Wilhelm Keitel (chief of staff of the German army), Lieutenant General Alfred Jodl (military operations), and Joachim von Ribbentrop (foreign minister).

In the midst of the legal preparations, Dodd toured other cities. On a brief excursion to Munich, he observed in a letter to Grace (August 25, 1945) that the “endless procession of refugees goes on—mile after mile on foot, on horse, in wagons. We passed [a]wagon train a mile long. It looked just like the pictures of covered wagon days in America—even the rounded tops on the wagons—horses and oxen doing the hauling, the men walking, the women and little ones riding. All heading back to Czechoslovakia, to Romania, to Bulgaria, to Austria, to places they call home. Believe me Grace, this movement across Europe is a pitiful thing—and it wrings my heart to see it day after day.”

Thomas J. Dodd and Grace Dodd, December 17, 1945. Archives & Special Collections, Thomas J. Dodd Research Center, University of Connecticut Libraries

Formal questioning began on August 28 with former army chief of staff Wilhelm Keitel. Writing to Grace (August 30, 1945), Dodd described Keitel as a gentle, polite, very proper man and wrote, “Sometimes I find myself liking him—and feeling sorry for him. He is a very bright man—in my opinion—and a very charming one too.” Keitel’s darker side came out in questioning on September 1, when he admitted to the slaughter of innocent men, women, and children, but only after devastating attacks against the Germans.

Questioning continued on September 3 with Franz von Papen, Germany’s chancellor in 1932 and then vice chancellor under Hitler in 1933 and 1934. Von Papen was a slim, gray-haired man who spoke English. Even as von Papen denied it, Dodd knew that he had forged an arrangement with Hitler to name him vice-chancellor if Hindenburg named Hitler to the chancellorship. Von Papen continued to deny the arrangement throughout his interrogation in the manner, Dodd wrote to Grace, of “a politician of the worst type.”

The next to be questioned was Dr. Arthur Seyss-Inquart of Austria, who was alleged to be part of the group that had devised the plan for the Nazi’s infiltration and eventual take-over of Austria. In response to Seyss-Inquart’s denial of these charges, Dodd inquired about communications between him and Hitler in February 1938. In a September 6 letter to Grace, Dodd wrote, “He admits conversations with Hitler, Himmler, and Göring; admits he was made head of Austrian government when the Nazi’s came, admits that he called Hitler on the phone, and all the details of these episodes, and then tries to state with conviction that he was no part of the plan.” The inconsistencies between recollections, statements, and documentation continued to add to Dodd’s burden as the prosecution staff worked to build the case against Hitler’s inner circle.

The summer weeks dragged on, and tension mounted as the trial neared. The significance of the painstaking work became increasingly more critical as Dodd slowly pieced together the puzzle of what exactly happened in the years leading up to all-out world war.

On September 25 Dodd had a breakthrough in his questioning of Dr. Wilhelm H. Scheidt, historian for the German High Command. Dodd challenged Scheidt repeatedly about his denial that he had burned the OKW (Oberkommando der Wehrmacht or High Command of the Armed Forces) files. Dodd’s relentless interrogation paid off when Scheidt admitted, “All right, I buried some of the most important ones at Berchtesgarden.” The admission was significant. The existence of even a portion of the files was of unimaginable value and had the potential to be a huge break for the prosecution.

Despite his progress, Dodd saw himself pushed to the side as the American staff expanded. The United States legal team had grown to approximately 250 people, and, according to Dodd, 150 of those were “superfluous and worse,” as he complained to Grace. It seemed, he wrote, as if he and Colonel Brundage were the only ones making advances on any of the interrogations, and yet he felt that others shared information only grudgingly, if at all. “It is clear to the both of us that we are not wanted by this crowd of jokers…Really there is not one outstanding man in an important place in this organization—saving Jackson himself. I never saw anything as bad. I can understand difficulty—personality conflicts, even some professional rivalry. But this is a maelstrom of incompetence. It is awful… You will understand if I return sooner than we anticipated,” he wrote on September 26, 1945.

Instead, two days later Dodd took a brief trip to Rome to clear his mind of the everyday frictions that were mounting as the opening of the trials neared. As the plane flew above Rome, Dodd was amazed and delighted with his first view of the picturesque city. In a letter to Grace September 28, he wrote “Rome is my city. First of all it is quite untouched by the war and for that reason it makes a good impression. But also I like its looks. We rode into Rome on the Apian Way—saw ruins of the ancient viaduct and the walls.” Through the good offices of Father Ed Walsh, head of the Georgetown University School of Foreign Service and consultant to the U.S. Chief of Counsel at the Nuremberg Trials, Dodd and Brundage met with Pope Pius XII. Dodd, a Catholic, received blessings for his family and a few rosaries for his children. Dodd and Brundage attended a very sentimental and private mass in the St. Ignatius in the Gesu Church and observed Anzio beachhead. “It is still a mess. Tanks, guns, destruction on all sides—much more than a year after that fearful affair. We passed the military cemeteries—rows of crosses—it does something to me.”

Shortly after his return, more permanent accommodations were made for the American staff in Germany. Dodd and Brundage moved into a beautiful six-room house. Dodd said they felt bad about the removal of the family who lived there, “but it is war, and this mission is a result of war.” They were also assigned a driver and car because of the distance between the house and their offices. Despite the improved housing, Brundage decided to resign and return home.

The interrogations were to be completed by October 17. On October 8, former Deputy Führer Rudolph Hess, Albert Kesselring, Hjalmar Schacht, and a few others arrived in Nuremberg for questioning. Dodd wrote of Hess, “He has no memory at all. We had Göring, von Papen, Haushofer and Bohle—all old friends—confront him. He didn’t know one of them… He has suffered a complete mental collapse.” Adding to the confusion, “Dr. [Leonardo] Conti, one of those who worked medical experiments on concentration camp inmates, hung himself in the jail….”

As the interrogations wound down, staff were released to return to the U.S. Some, including Dodd, had begun to consider potential opportunities at home. The work was taking its toll. Dodd admitted to Grace (October 15, 1945) that he “was now in one of those dead spaces mentally” due to the daily exposure to destruction and devastation both around him and described in the interrogations. Dodd wrote to Grace, “Be assured I will not be here for the trial itself. It will not start until December and will run for many weeks. I feel that I cannot remain here after December 1 and by that time I will have had all that this experience can give to anyone.”

But on October 22, 1945, he received word that his role had changed. “This has been a rather unusual day,” he wrote to Grace. “About six o’clock I was back in my own office when I got a call from Colonel Storey. He came down and showed me an order issued by Jackson today reorganizing the whole staff. I was named with three others to the top of the staff and with full authority over the whole organization!! I was really amazed.”

Dodd now vowed to “do my best to put this case on its feet.” Once that task was completed, he would be content to return to Connecticut and his family. “You see I have worked on this matter in two capacities. 1. As an interrogator talking with the principal defendants and witnesses. 2. As a member of the legal board of review to prepare the case for trial. These two make up a substantial contribution to the whole effort and I feel that I can rest at this point,” he wrote to Grace on October 30. In several letters in early November he reported, “The pressure is on for fair now. Today Jackson published a memorandum naming trial counsel and I was included with nine others. … It seems strange to me that I should be catapulted onto this trial staff. Maybe it is a great opportunity. The world will watch this case—and in my judgment it will make history…I hope I can do a job that will be worthwhile.”

Dodd served as vice-chairman of the review board and executive trial counsel, the lead prosecutor for the United States. As executive trial counsel, he was the second-ranking U.S. lawyer and the supervisor of the day-to-day management of the U.S. prosecution team. He shaped many of the strategies and policies through which this unprecedented trial took place and frequently dealt with other Allied legal notables such as Sir David Maxwell-Fyfe of Great Britain and Lieutenant General Roman Rudenko of the Soviet Union. Dodd spent considerable time focused on proving the charge of conspiracy to wage aggressive war and consequently cross-examined German industrialists as well as military and political leaders. He reconstructed the will of the last president of the Weimar Republic, Paul von Hindenburg, to reveal that the Nazis had falsified this document to help justify Chancellor Adolph Hitler’s consolidation of power.

Dodd presented portions of virtually every aspect of the prosecution’s case. He developed a degree of notoriety for his dramatic presentations during the trial. As one of the few civilian lawyers among the U.S. prosecutors, Dodd privately expressed an acute self-consciousness of his unique status as well as the intense loneliness common among Nuremberg staffers separated from their families. Throughout his time in Nuremberg, Dodd questioned many things, but never the significance of the rule of law in holding individuals accountable, for the first time in history, for their actions during war.

Editor’s note: Later in his career, Dodd, then a second-term U.S. Senator, was censured by the U.S. Senate for financial improprieties stemming from misuse of campaign funds for personal expenses. Find out more at the Office of the State Historian’s TodayinCTHistory.com; see the entry for June 13, 2020.

Betsy Pittman is University Archivist at the University of Connecticut. Owen Doremus, an Edwin O. Smith High School student in Fall 2015, provided research assistance.

This story is adapted from a series of blog posts at blogs.lib.uconn.edu/humanrights. The letters from Thomas Dodd to his wife Grace Dodd can be found in Letters from Nuremberg, My Father’s Narrative of a Quest for Justice by Christopher J. Dodd with Lary Bloom (Crown, 2007).

Explore!

Receive each beautiful and informative issue — Subscribe Today!

Read more about Connecticut in World War II in our Fall 2020 issue and on our Connecticut at War TOPICS page.