by David Corrigan & Mark H. Jones

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. WINTER 2013/14

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

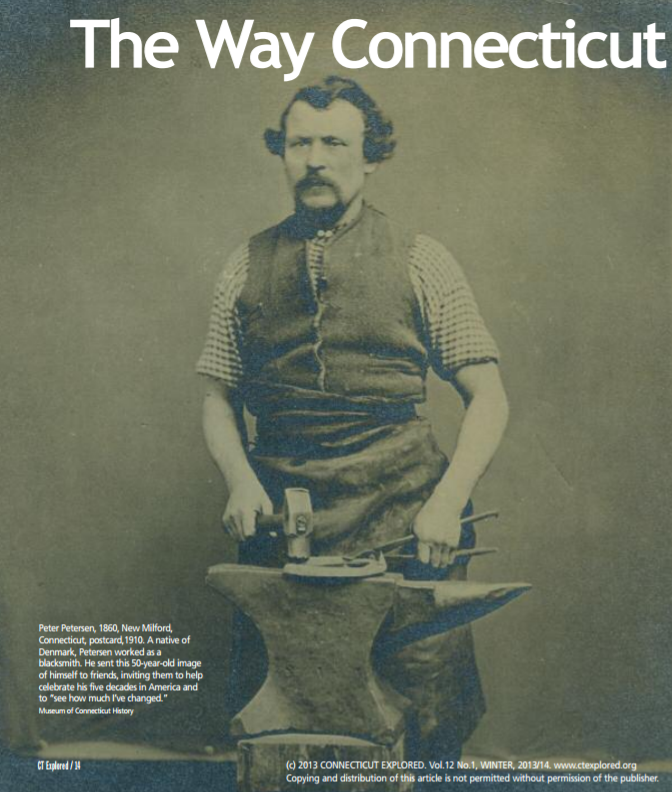

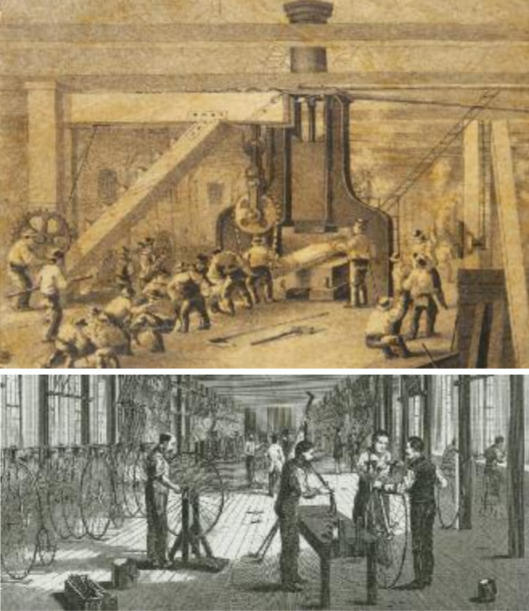

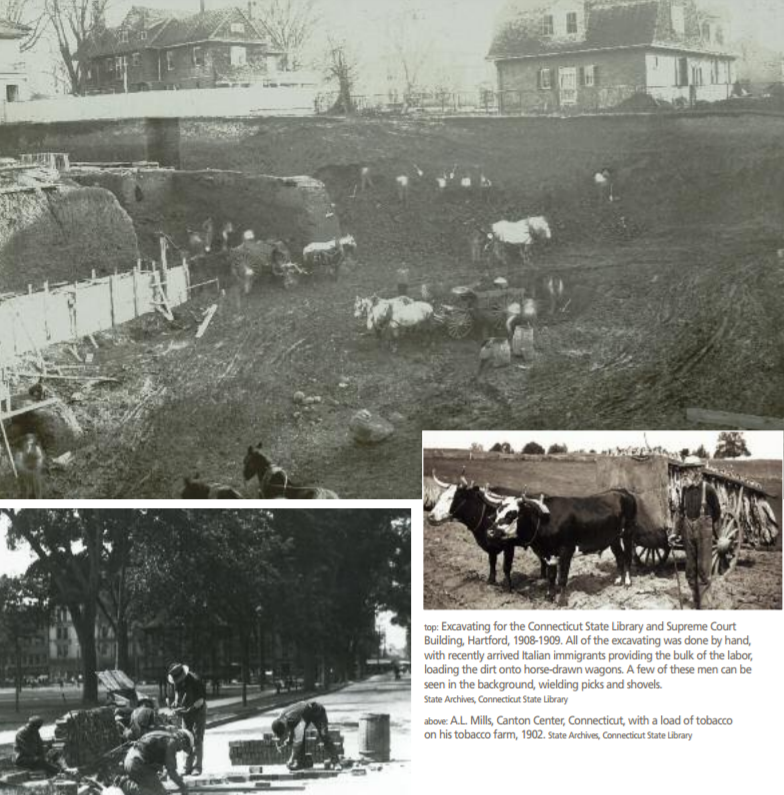

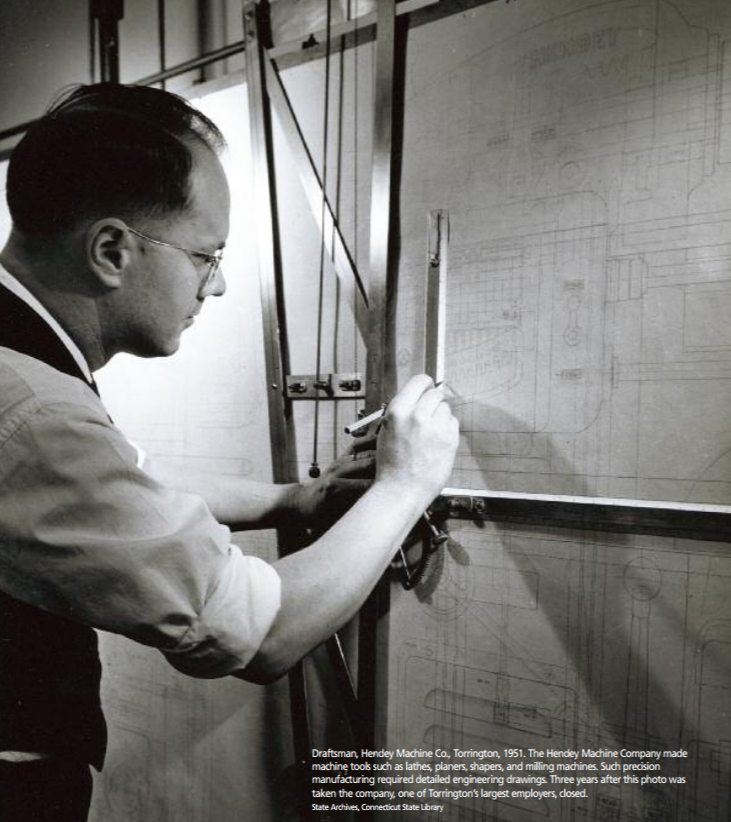

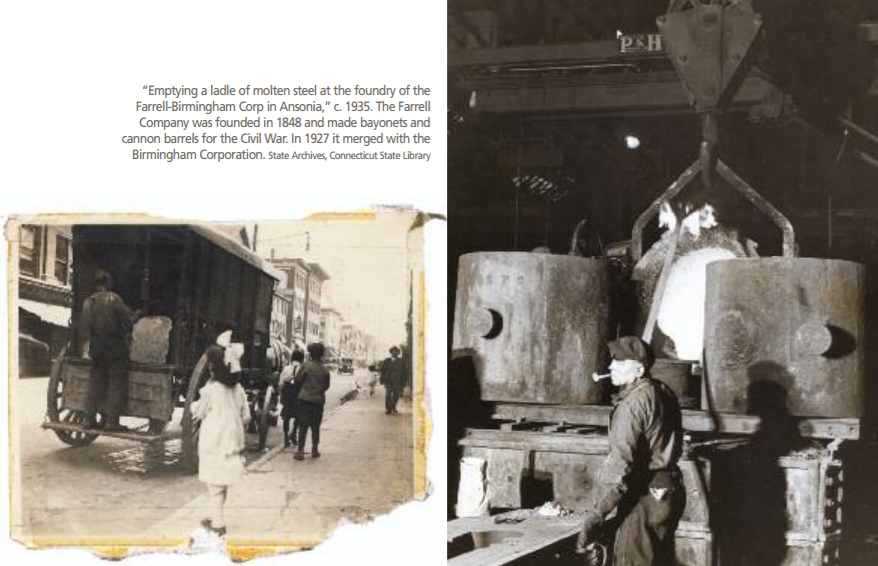

In 19th- and early 20th-century Connecticut, the experience of work changed dramatically as many traditional trades and crafts were rendered obsolete by mechanization. Many skilled mechanics and artisans who had worked alone or in small shops suddenly found themselves part of the large work forces required by the state’s burgeoning factories. New professions such as typist, engineer, and draftsman appeared, while assembly lines became more common and agriculture became mechanized.

In two world wars, women proved that they could perform complex operations on machine tools with great precision, but old gender prejudices gave them this opportunity only during wartime. As techn

ology advanced, more new jobs were created and women began making headway in employment,though often not at equal wages with men. However, not all work suddenly changed. The iceman was still delivering ice in the 1940s to those who could not afford refrigerators.

These images depict jobs that were once plentiful in

Connecticut but that either no longer exist or that continue in

a form greatly altered by technology. By the mid-19th century, Connecticut industry had developed precision manufacturing (Colt’s and Pope Bicycle images) and heavy manufacturing (Ames Iron Works and Farrell-Birmingham images). White collar jobs developed, too, as seen in the State Library images. But tobacco farming, oystering, and construction, as shown in images here, represent some of the manual labor occupations that continued well into the 20th century in much the same way as they had for generations.

Bicycle room, from “The Manufacture of Sewing Machines and Bicycles. The Weed Sewing Machine Factory,” Scientific American, March 20, 1880. Col. Albert Pope contracted with The Weed Sewing Machine Co. in Hartford in 1878 to manufacture bicycles. This Scientific American article shows a pre-assembly-line mode of production using the vast array of parts produced elsewhere on the premises. Museum of Connecticut History

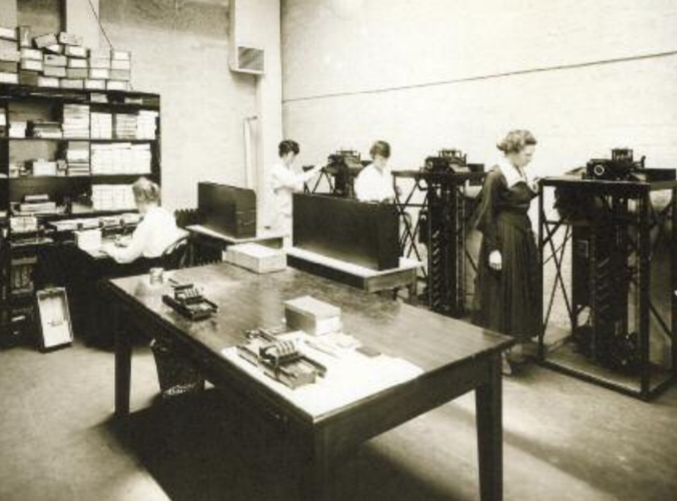

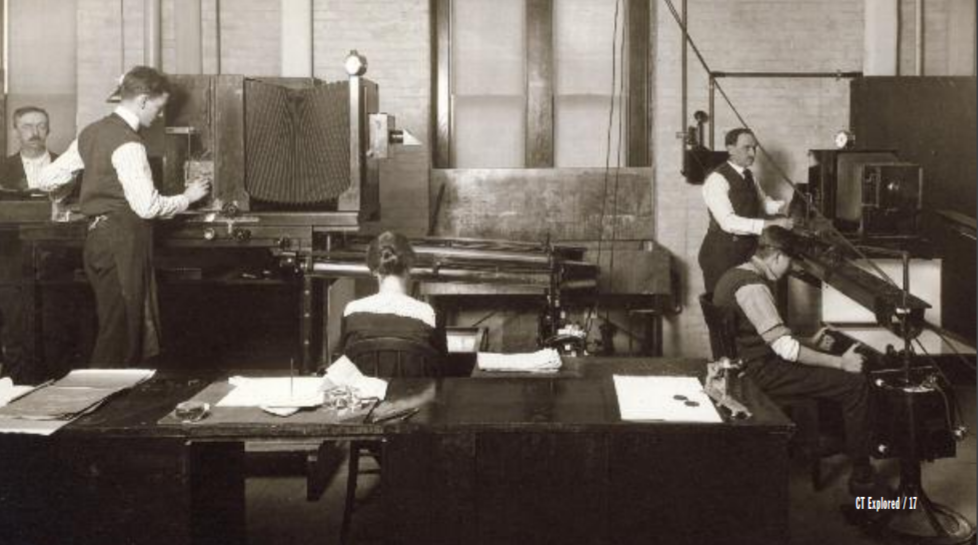

Military census, 1917, Connecticut State Library. In March 1917, one month before the U.S. declared war, Governor Marcus Holcomb launched a census of all men over the age of 16. Individuals filled out one-page forms or dictated answers to a census taker. The data was punched into Hollerith cards in the machine on the table in the foreground. Workers sorted the cards using the machines in the background, and the results were tabulated by machine. Five Connecticut insurance companies lent machines and technical assistance to the state. Note that women were employed in this occupation. State Archives, Connecticut State Library

Photostat department, Connecticut State Library. In 1917, State Librarian George Godard purchased a state-of-theart duplicating machine called a Photostat camera like the one used by the Library of Congress. It was used for preserving historical records and duplicating bills for members of the Connecticut General Assembly. State Archives, Connecticut State Library

“Oystering in Connecticut Waters,” c. 1935, Oyster Institute of North America. State Archives, Connecticut State Library

David Corrigan is curator of the Museum of Connecticut History. Mark H. Jones is state archivist at the Connecticut State Library.

Explore!

Read more stories about work in Connecticut on our Labor History TOPICS page.