By Vivian Zoë

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Fall 2021

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

The actions of America’s early philanthropists don’t necessarily sit easily with us today. We may be tempted to view with skepticism that which was once considered altruistic. But it’s worth examining the philanthropy of our American forebears, to understand their actions within the context of their times and environment.

A great Connecticut example from the Victorian era is the Slater family of Norwich, in particular John Fox Slater (1816 – 1884) and his son William Albert Slater (1857 – 1919). The Slater name is ubiquitous in Eastern Connecticut and Rhode Island for its association with textile manufacturing and the family’s influence and philanthropy in the late 19th century. Among John Fox Slater’s notable gifts was the establishment of Norwich Free Academy, founded in 1854, and William’s gift to the academy of Slater Memorial Hall, built in 1886.

The John F. Slater Fund

John Fox Slater received a medal of thanks from the United States Congress for establishing, in 1882, the John F. Slater Fund for the Education of Freedmen. Two years before he died, he established the fund with a gift of $1 million to uplift the “recently emancipated population of the Southern States,” as Slater’s “Letter of the Founder” in the organizing document reads. He went on to explain that he felt that formerly enslaved men needed education to become productive, contributing citizens and voters.

As the New York Tribune reported on April 13, 1882, Slater claimed to have conceived the plan at the start of the Civil War. While this might seem prescient, it is possible or even likely that he understood that his wealth derived in large part from the cotton he acquired so inexpensively from plantations and enslaved labor in the South. Thus, I suggest, the Slater family philanthropy established early on a pattern of returning wealth to uplift those who had suffered for that wealth.

According to the Tribune article, Slater intended the John F. Slater Fund to found and support schools in the South to create a corps of trained male and female “colored” teachers. The fund’s first board chairman was former U.S. President Rutherford B. Hayes; William A. Slater was a trustee. Under Hayes’s leadership the fund initially supported mostly manual and agricultural training rather than academically rigorous education. In time institutions funded by the John F. Slater Fund developed academic courses, including those in medicine and education. Slater Industrial Academy founded in 1892, for example, became Winston-Salem State University in 1969. The fund later joined with the Peabody Fund and the Southern Education Fund, all of which helped to found and continue to support America’s historically black colleges and universities.

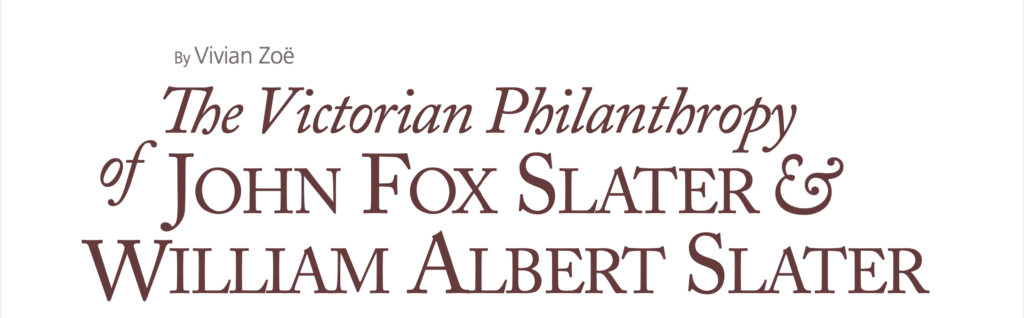

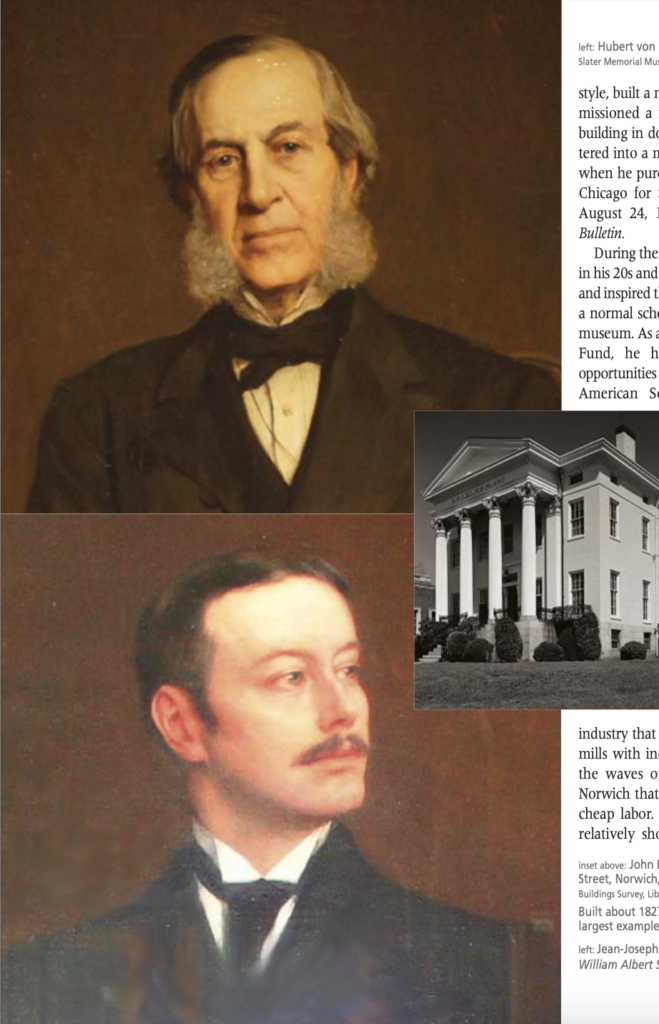

top: left: Hubert von Herkomer, John Fox Slater, 1883. bottom: Jean-Joseph Benjamin-Constant,

William Albert Slater, 1887. Slater Memorial Museum; inset: John Fox Slater House, 352 East Main Street, Norwich, c. mid-20th century. Historic American Buildings Survey, Library of Congress

Built about 1827, this brick house is one of the largest examples of the Greek Revival in the area.

William Slater’s Legacy

William Albert Slater was deeply influenced and shaped by his father’s transformative philanthropy and vision. As the wealthiest man in Norwich and, arguably, Connecticut, William Slater was the frequent subject of stories about his philanthropy, including in newspapers in Norwich, New York, and Boston. Within a decade of his father’s death, William Slater had inherited vast wealth, married Ellen Burdett Peck (1858 – 1941) of Killingly, Connecticut and Worcester, Massachusetts, renovated the largest mansion on Broadway in Norwich in the new Aesthetic Movement style, built a memorial to his father, commissioned a new, state-of-the-art office building in downtown Norwich, and entered into a monumental real estate deal when he purchased the Honore Block in Chicago for $800,000, according to an August 24, 1888 story in The Norwich Bulletin.

During the same period—while he was in his 20s and early 30s—he also endowed and inspired the founding of an art school, a normal school, a nursing school, and a museum. As a trustee of the John F. Slater Fund, he helped establish educational opportunities for African Americans in the American South. I suggest that his successes and disappointments, his connections to political leaders, and the effect of his philanthropy on the built environment in many ways stemmed from his solid “Victorian” background and education in Norwich, Connecticut.

Coming of age in America during and just after the Civil War, the younger Slater would have been keenly aware of the Southern cotton industry that provided his family’s textile mills with inexpensive materials and of the waves of European immigrants to Norwich that provided his factories with cheap labor. Norwich transformed in a relatively short 25 years, from around 1825 to 1850, from an agrarian economy to an urban, industrial one. As corporate records for Slater enterprises in several repositories, including Brown University, the Baker Business Library at Harvard, and the Thomas J. Dodd Center at University of Connecticut, reveal, the rise and decline of the Slater influence across New England, from Rhode Island to Massachusetts to Connecticut, follows this time frame.

Throughout the 19th century, industrialization generated both great wealth and tremendous poverty and illness in the United States. Government played a much smaller role in regulating business and in supporting human welfare than it does today. In the United States, private donors largely supported and governed education until the middle of the 19th century; in fact, pressures to require and fund mandatory public education often caused great controversy. Norwich Free Academy (NFA), independently governed and privately endowed, was founded in 1854 in response to such political strife in Norwich. John Fox Slater and his brother-in-law Russell Hubbard were original founders and corporators of the academy. William Slater graduated from the school in 1875 and served as a trustee of the institution for decades and as president of the board from 1891 to 1893.

Norwich Free Academy & Slater Memorial Hall

What is today called “Victorian” by Americans, referring to the mid-to-late 19th century, coincided with the latter part of British Queen Victoria’s reign (1837 – 1901). In the United States, architecture of the late 19th century, though, took its influences more from continental Europe than from Great Britain. Around the American Centennial, our version of “Victorian” reflected the new nation’s evolving cultural identity in an amalgam of eclectic architecture, as both the Italianate and Romanesque styles popular at the time attest. A wonderful example of this phenomenon is Slater Memorial Hall on the campus of Norwich Free Academy.

William graduated from NFA at age 17. After a year of European travel and study, he entered Harvard, where he studied the classics and fine art. When he was 28 he presented Slater Memorial Hall to the academy to honor his father. Originally conceived as an “athenaeum” for the community to enrich mind, spirit, and body, the building was designed by architect Stephen Earle (1839 – 1913), who also designed academic, cultural, and commercial buildings, churches (including one in Worcester that bears a resemblance to Notre Dame de Paris), fire stations, mills, warehouses, and residential structures including apartment houses and tenements. Earle was educated and began his career in Worcester. He apprenticed for the New York design firm Calvert Vaux, which designed that city’s Metropolitan Museum of Art. In 1887 Earle designed Norwich’s Carroll Building in the Romanesque Revival style (listed in 1982 on the National Register of Historic Places). Earle’s late-19th-century designs often combined Gothic, Norman, French Second Empire, Romanesque, Neoclassical, and Palazzo styles in a single structure. They perfectly matched the eclectic tastes of the late-19th century in the United States.

Slater Memorial Hall cost $160,000 (the equivalent of $3.16 million today) to build. It included the school’s first purpose-designed library, an elegant wood-lined room on the second floor with soaring overhead trusses. The basement held small classrooms, and the ground level had an auditorium with an ample stage, 500 seats, and two gathering spaces at the rear, separated, when needed, by massive, triple-hung, leaded-glass windows. The building’s remarkable second floor is open in the center to the third floor, surrounded by a mezzanine trimmed in various native woods and ornamental columns with carvings in an acanthus motif. Cast and wrought iron, made possible by the ongoing industrial revolution and the Union’s recent Civil War military-industrial complex, support the lofting space.

The third level, attic, and topmost floor had space for an indoor track, a gymnasium, and art classes, including a north-facing skylight perfect for an atelier. In addition to the essential element of every Romanesque building—the round arch—the building’s tourelles, nearly cylindrical tower, and loggias are decidedly of the Romanesque Revival style. Finishes and treatments, not normally identified as Victorian, include Moorish, Egyptian, and Corinthian in-situ carvings in red sandstone and granite, oak, maple, cherry, and terra cotta. Interior ornamentation includes hand-wrought iron, mosaic tile, and stained and leaded glass.

When Slater Memorial Hall opened in 1886, Slater asked his former Harvard art history professor, American philosopher, critic, literatus, and aesthete Charles Eliot Norton to deliver the dedication. Slater Memorial Museum was opened in the space initially intended as the gymnasium in 1888. NFA’s third Head of School, Robert Porter Keep, a classics scholar, envisioned displaying the now-iconic plaster cast collection there, which Slater, no doubt because of his familiarity with both Harvard and European cast collections, funded at a cost of $60,000 ($1.58 million today). In addition to annual allotments to pay museum staff, Slater donated his collection of Native American artifacts and a magnificent history painting by John Denison Crocker telling the story of the rivalry between the local Mohegan and Narragansett tribes. He also loaned treasures purchased on the grand tour he and his wife Ellen took from 1894 to 1896 for temporary exhibitions to attract repeat visits.

A Patriarchal Philanthropy

Both John Fox Slater and his son William employed the “mill village” form of management of labor brought from England by their ancestor Samuel Slater in the 18th century. The system was based on the so-called three pillars of colonial New England life: family, church, and community. Within the mill village, owners supplied (and charged for) housing, stores, schools (when there were any), recreation facilities, and churches. Ostensibly, the mill village appeared beneficial to workers, but in an environment of profit-motivated owner control, abuse was not uncommon. In some cases, children were compelled to enter the workforce well before puberty and entire families labored in the mill. In addition, families depended upon their employers for housing, supplies, and even spiritual activities. Thoroughly patriarchal, the mill-village paradigm is seen by many today as repressive, especially as it discouraged organized labor. [See “A Strike Transforms a Village,” Winter 2019-2020.]

The Slaters expanded the mill-village model into philanthropic community and economic development by which much of the fantastic wealth accumulated via the model was funneled back into services for the workers. In 1890, seeing the potential of the Slater Museum’s cast collection as a laboratory for art students and a way of improving the talent pool for a burgeoning manufacturing climate in Norwich, Slater proposed the establishment of an art school associated with NFA. The school, housed within the Slater Museum but relatively independent, would train “tradesmen” (including women) of the era to become designers. The school taught drawing (using the cast collection as subjects), modeling with clay, and fine engraving and etching. The schedule of class times accommodated working adults. Slater also helped to build and support the local theater, the YMCA, Park Church, and a park planned for 1893. He sponsored the William A. Slaters, a semi-professional baseball team whose wins and losses were reported regularly in The Norwich Bulletin.

In 1891 Slater joined William Wolcott Backus to establish the William Backus Hospital. While Slater’s gift was the larger, he stepped aside for Backus to assume the naming opportunity. Slater then helped to fund and support a nurse-training school to provide the new hospital with a professionally prepared workforce. The Norwich Bulletin reported his gift and the fact that he spoke at its first graduation ceremony.

Even before and concurrent with many of these philanthropic endeavors, in 1889 Slater nearly single-handedly established the Norwich Normal School. Based upon the success he had witnessed in communities in the South through the John F. Slater Fund, his Norwich venture operated for six years. NFA housed the school on its campus and managed staff salaries, but Slater supported it financially. The Normal School’s purpose, as The Norwich Bulletin noted, was “… to furnish young women, having the equivalent of a high school education, a thorough and adequate preparation for the teacher’s calling.” In 1893 the school received a prestigious Certificate of Excellence at the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago for “excellence of plan and for the thorough training of teachers and for results.” The New York Herald reported that the Norwich Normal School was Slater’s fondest project.

By 1896, though, Slater’s offer to expand and endow the school ran afoul of local political support out of the fear that an endowment would obligate the local school board to operate it in perpetuity. With the loss of the school’s director, the school foundered and closed in 1896. The Norwich Bulletin’s reports reveal the community’s love-hate relationship with wealthy Norwich citizens who dominated through social good and beneficence. The defeat of the normal school’s expansion may have been partially responsible for Slater’s permanent departure from Norwich in 1896, as the Bulletinopined at the close of the struggle.

Slater Leaves Norwich

By the 1890s Slater was not a well man. News reports referred to him as “infirm” and suffering from “creeping paralysis.” His personal physician, Witter Kinney Tingley, also an NFA alumnus, recommended extended ocean voyages for fresh air and a relaxed lifestyle. Slater’s first yacht, the Sagamore, was replaced with the larger, more elegant and faster Eleanorfor a grand tour beginning in 1894 that would last well over a year and completely circumnavigate the globe. [See “The Slaters Go Round the World,” Winter 2011-2012.]

His return from these travels marked plans to leave Norwich. On April 8, 1896, he was off to the coastal French town of Biarritz, known for salt-bath cures and ocean and mountain air. The family later moved to the French Riviera for six years before relocating to Washington, D.C. In the first decade of the 20th century, the Slaters purchased summer homes in Massachusetts, including an estate in Lenox and a massive summer “cottage” on the water in Beverly.

When Slater and his family left Norwich, their land was sold and structures dismantled. Much of the land was developed into a housing complex to accommodate a growing industrial workforce. William Slater died in Washington, D.C., at the end of February 1919. On March 1, Norwich’s downtown shut down in his honor. A modest funeral took place at Park Congregational Church not 100 yards from the memorial he had built for his father. Reverend Samuel H. Howe eulogized Slater as a man who was generous, cultivated, and interested in the arts and literature. He observed that “one had only to look about us at the church, at the Academy, at the hospital, to keep his memory fresh and forever enduring among us.”

Vivian Zoë was executive director of the Slater Memorial Museum. She last wrote “Embracing Ellis Ruley,” Winter 2018-2019.

Explore!

Slater Memorial Museum

108 Crescent Street, Norwich

slatermuseum.org, 860-425-5563

Walking Tour of Millionaires’ Triangle, Norwich

See “Norwich’s Millionaires’ Triangle,” Summer 2021

walknorwich.org/millionaires-triangle-trail/

“The Slaters Go Round the World,” Winter 2011-2012

“A Strike Transforms a Village,” Winter 2019-2020

GO TO NEXT STORY

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!