(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Winter 2019-2020

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

Forty years ago, Hartford-based M. Swift & Sons was the “largest supplier of gold leaf in the United States,” according to The Hartford Courant, and about 50 years back, the company’s publicist claimed it was the “world’s largest producer” of both gold leaf and stamping foils. But the tide was about to turn; the factory closed in 2005. Today Community Solutions’s $34 million adaptive reuse project at the Swift Factory site is perhaps the most significant investment in the neighborhood since. Expected to open in March 2020, Swift Factory, a food business, health, and jobs hub for North Hartford, as its website describes it, is expected by its developers to bring 150 permanent jobs to a neighborhood with a reported 27.1 percent unemployment and 45.3 percent poverty rate. The construction phase alone has created 225 direct and 295 supplier jobs, with 30 percent of those going to city residents. What was old and blighted is new and shiny again, with this renovation representing a return of jobs to the neighborhood. It fulfills Community Solutions’s mission “to end homelessness and the conditions that create it,” by “spurring job growth, economic development, and community health in North Hartford,” as the project’s website states.

The Rise of M. Swift & Sons

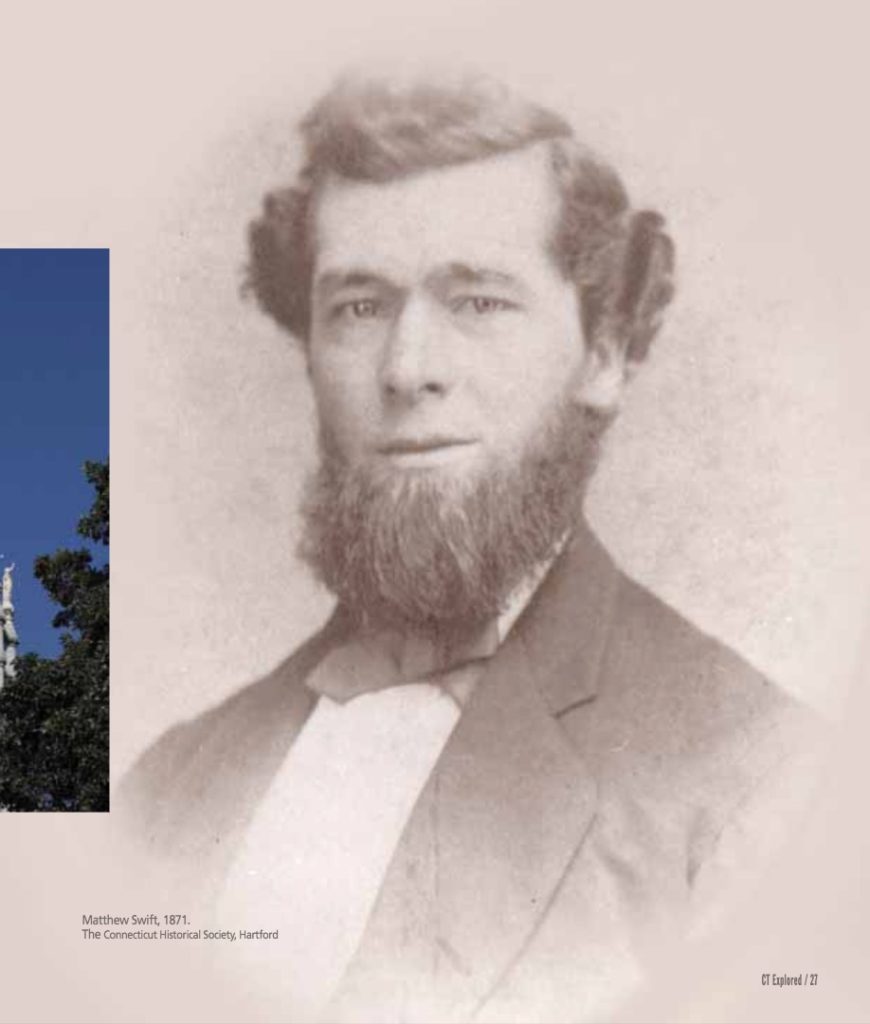

Before Matthew Swift (1842 – 1912) built his fortune, he had to learn his craft, beginning at age 14 in his homeland, England. He completed his apprenticeship as a gold beater (someone who hammers gold into gold leaf) seven years later, in 1863. Emigrating to the United States the next year, he quickly found himself on none other than Gold Street in downtown Hartford, working as a journeyman gold beater.

In 1812 Marcus Bull introduced the gold leaf industry to Connecticut’s capital city, according to the Swift Factory nomination to the National Register of Historic Places prepared by Lucas Karmazinas. The enterprise evolved over the years, with several others succeeding Bull, including Jonathan Ney, for whom Swift would work on Asylum Street for several decades. In the 1870s while Swift worked there, J. M. Ney & Company manufactured the gold leaf for the new State Capitol in Hartford.

As Karmazinas describes it, the process of making gold leaf began with quarter-inch-thick gold bars, 12 inches long by 1.5 inches wide. The bars were rolled to a thickness of 1/1000 of an inch and cut into squares. The squares were then dusted with calcium carbonate applied with a brush—often a hare’s foot—and placed between a thin membrane made of the outer layer of an ox intestine. These were then stacked, in as many as 300 layers, and repeatedly struck with a 16-pound hammer. The squares were cut again into smaller squares and the process repeated with a 10-pound hammer; the squares were then placed in a mold and struck with a 6-pound hammer. When finished, a layer of 280,000 leaves stood just an inch high.

Swift purchased land on the sparsely developed Love Lane in 1871. It was not until 1887 that he would build a practical farmhouse on site (which still stands), just as he left J.M. Ney & Company to found his own gold-beating concern. When Swift faced early financial struggles, Ney, his former boss and friend, helped him out. The business expanded, beginning with the creation of a shop building in 1895 and followed by numerous additions, one of which was achieved by raising the original first floor up and laying bricks below for a new level.

The Connecticut State Capitol’s dome is covered with gold leaf manufactured by M. Swift & Sons. photo: Carol M. Highsmith, George F. Landegger Collection, Library of Congress

By 1902, according to Karmazinas, M. Swift & Sons had become the largest gold-leaf-beating firm in Connecticut “and one of the most significant in the country.” Despite Swift’s death in 1912, the business thrived under his sons Matthew H. Swift and Ernest Swift and, later, his grandson M. Allen Swift. With the Swift family running the factory, new building additions were constructed through 1948. In 1930 the company broke into the substantial South American market, exporting 2,400,000 gold leaves to Argentina between 1930 and 1932. The company added aluminum beating to its repertoire, producing 99 percent of the beaten aluminum used in camera-bulb filaments in the United States in 1936, The Hartford Courant reported (December 26, 1936). Swift’s gold leaf re-gilded the State Capitol dome in 1942 and 1965, was used on the ceilings and balconies of the Metropolitan Opera House in New York City, and added gleam to the dome of Aetna’s Hartford headquarters. The company continued to innovate, becoming “one of the country’s prominent manufacturers of gold leaf, sized gold, bronze, roll leaf, and color foils,” according to Karmazinas.

A host of factors in the 1960s led to the decline of M. Swift & Sons. As Karmazinas notes, “The establishment of a free market for gold in 1968, combined with shifting tastes and technologies, … the proliferation of neon and plastic, as well as the use of synthetic materials in printing and decorative accents, drove the slow decline of the gold beater’s trade.” Businesses and residents fled Hartford around the time the interstate highways were finished. Among the manufacturers that left Hartford’s North End were the Proctor-Silex Co. in 1957 and Poles Syrup & Paper Co. in 1987, both of which had been located within a few blocks of Love Lane. Labor unrest also played a role: Teamsters Local 1035 organized a strike of 50 workers against the Swift plant in 1977, The Courant reported, citing complaints about wages, benefits, and hazardous workplace conditions. Although half of Swift’s employees were women, pay disparities were stark.

The gold-leaf factory closed in 2005, following the death of M. Allen Swift. In 2010 the Swift family donated the property to Common Ground, now called Community Solutions. The site was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2013 “because of the important role the company played in the economic and industrial development of the City of Hartford,” according to the National Park Service.

A New Swift Factory

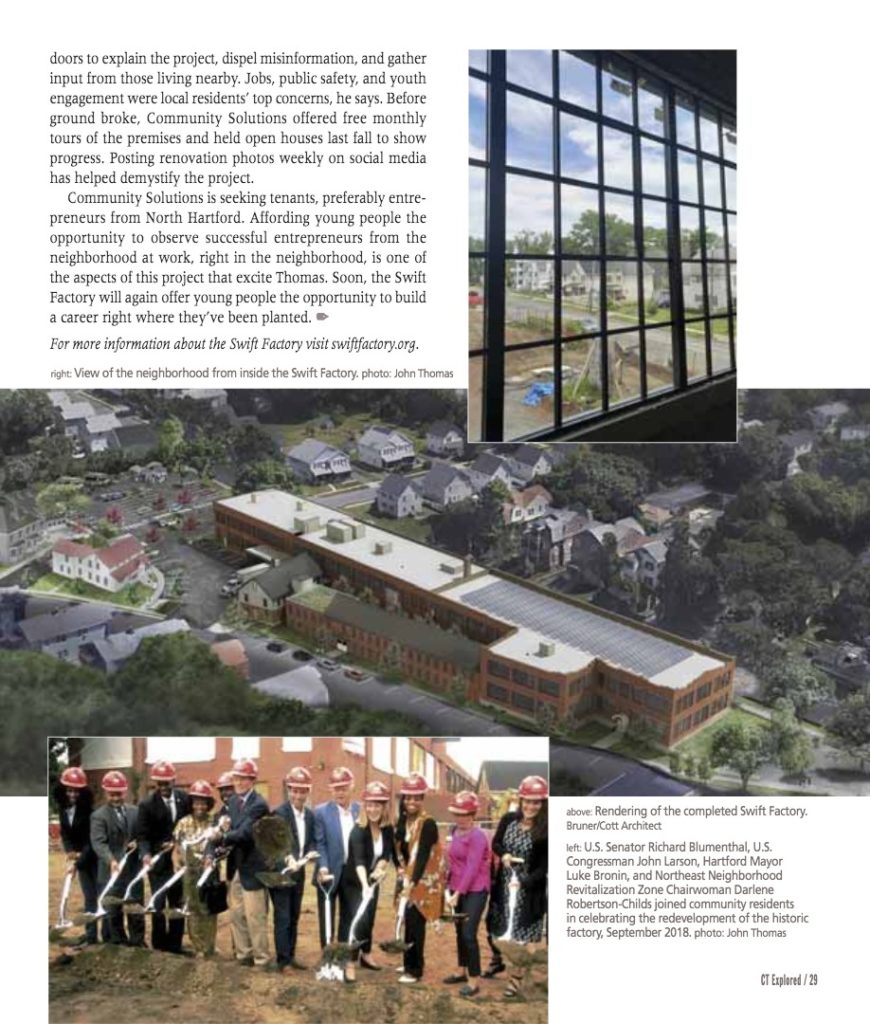

The return of accessible jobs to the neighborhood may be the most meaningful nod to the Swift legacy. The factory building, a brick complex built in six stages over 48 years beginning in 1900, already has two anchor tenants committed: Bear’s Smokehouse BBQ and Freshbox Farms. Almost 5,000 square feet in the same building will be dedicated for a food-business incubator, and nearly 10,000 square feet is being converted into a co-working space. Private and shared kitchens can be rented for commercial use. Office and desk rentals are slated to be competitively priced, with the developers aiming to attract a different clientele from that which might gravitate toward corporate downtown.

The Grey House, which serves as Community Solutions’s offices during construction, will be a community health hub. It will provide services in what the Hartford Health Equity Index ranked in 2012 as the neighborhood with the worst “health equity.” This building, with its Colonial Revival influences, had been one of the two homes for the Swift family, who lived on site for most of the factory’s operation. Finally, the site’s White House—the original building and farmhouse, which later served as a cafeteria—is slated to become a community meeting space.

Outside, a bioswale has been added around Garden Street to manage stormwater, an important consideration given the site’s proximity to Gully Brook. To break up the mass of the factory complex, a cross-site path will improve walkability between Keney Park and the Mt. Moriah community garden. A bike rental program is being considered, and public art will be added in the pocket park located at Five Corners, increasing connectivity to the neighborhood.

Outside, a bioswale has been added around Garden Street to manage stormwater, an important consideration given the site’s proximity to Gully Brook. To break up the mass of the factory complex, a cross-site path will improve walkability between Keney Park and the Mt. Moriah community garden. A bike rental program is being considered, and public art will be added in the pocket park located at Five Corners, increasing connectivity to the neighborhood.

To get to this point, Community Solutions needed to earn community buy-in. John Thomas, who lived across the street from Swift Factory and now resides a few blocks away, was just the person to connect with neighborhood residents skeptical that this development would reach fruition. Thomas, community engagement coordinator for Community Solutions, estimates he knocked on a thousand doors to explain the project, dispel misinformation, and gather input from those living nearby. Jobs, public safety, and youth engagement were local residents’ top concerns, he says. Before ground broke, Community Solutions offered free monthly tours of the premises and held open houses last fall to show progress. Posting renovation photos weekly on social media has helped demystify the project.

Community Solutions is seeking tenants, preferably entrepreneurs from North Hartford. Affording young people the opportunity to observe successful entrepreneurs from the neighborhood at work, right in the neighborhood, is one of the aspects of this project that excites Thomas. Soon, the Swift Factory will again offer young people the opportunity to build a career right where they’ve been planted.

For more information about the Swift Factory visit swiftfactory.org.

Kerri A. Provost is the creator of RealHartford.org and co-producer of the Going/Steady podcast.