(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Winter 2005/2006

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

All photos courtesy of the Lyme Historical Society Archives, Florence Griswold Museum.

“Please have my room ready, as I may tumble in any time now.”

William S. Robinson to Florence Griswold, April 10, 1908

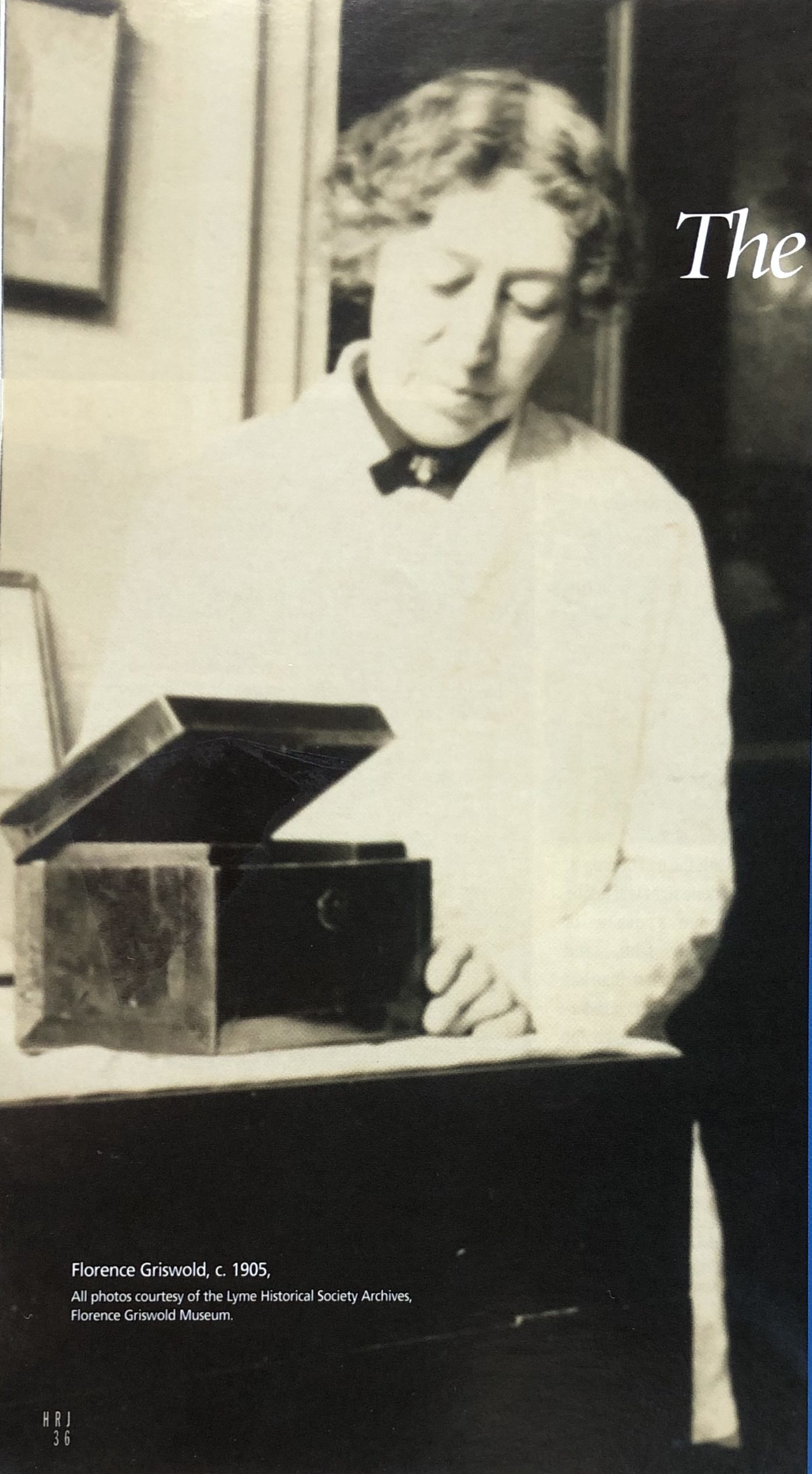

Florence Griswold’s home in Old Lyme became the center of an important artists’ colony in the first decades of the 20th century. More than 200 artists and noted figures, including painters Childe Hassam, Willard Metcalf, Henry Ward Ranger, and William S. Robinson, and presidential aspirant Woodrow Wilson, whose first wife Ellen Axson Wilson was an artist, came to stay at Miss Florence’s, dubbed the Holy House by its guests. For many artists, it truly became a sacred destination, but the moniker was also a play on the Bush Holley House in Greenwich, a “rival” boarding house for artists.

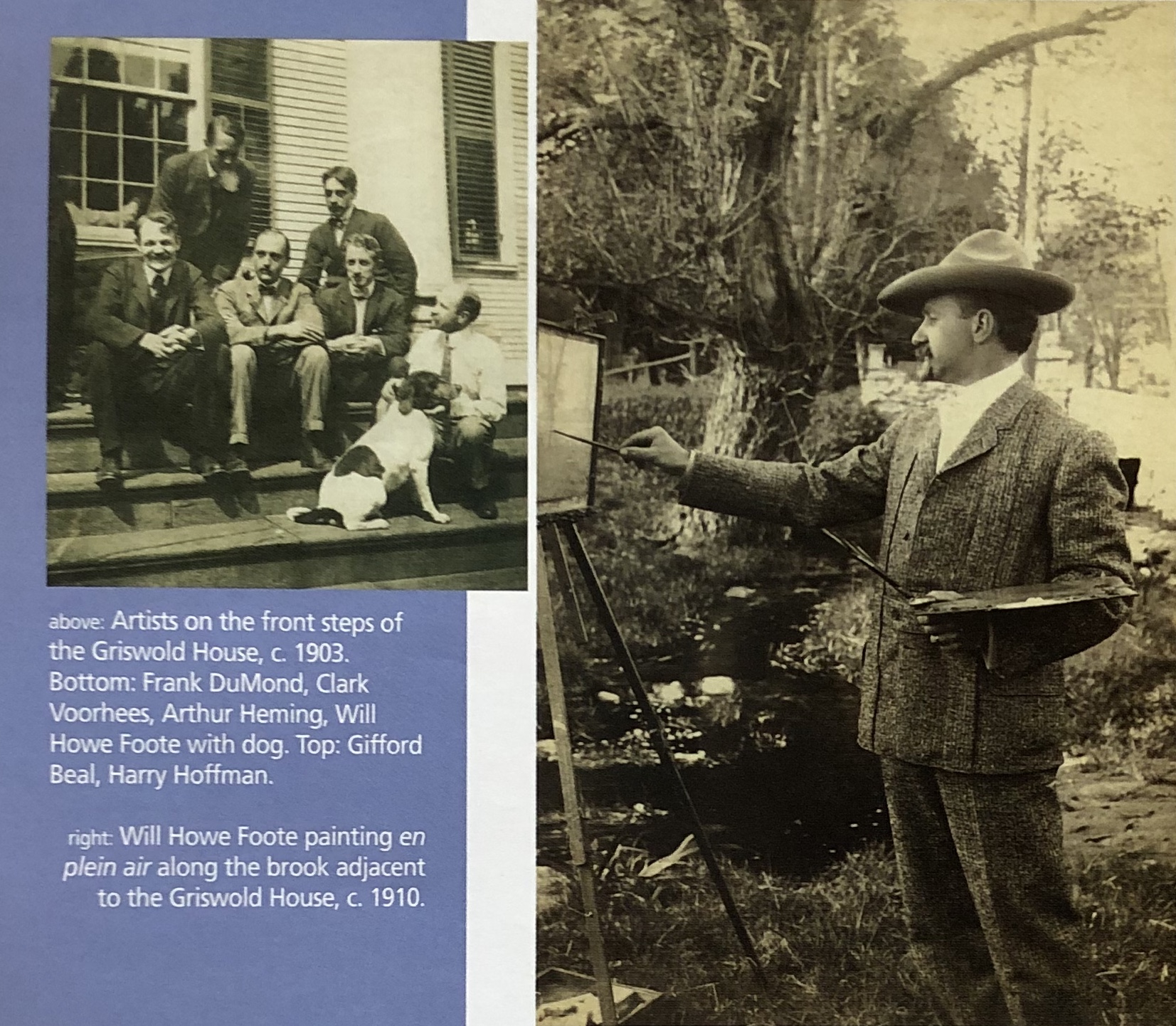

For $7 a week, guests could stay in the house, use a studio on the property, guests could stay in the house, use a studio on the property, and enjoy communal meals with good food and conversation. The atmosphere was lively, with artists constantly coming and going; as Wilson commented, “You no sooner get interested in them than they are off.”(1) With palette and paints in hand, artists set out with portable easels to paint en plein air in the Lyme countryside. They returned at the end of each day to the Holy House for evening games, concerts, and midnight raids on the icebox. The country boarding house, with Miss Florence herself as central figure and guiding force, provided fertile ground for the cultivation of a major movement in American art.

Today, the Florence Griswold Museum, designated a National Historic Landmark in 1993 and a museum since 1947, is owned and operated by the Lyme Historical Society, Inc. Restorations to be completed in June 2006 aim to recreate the boarding house’s bustling ambiance and illustrate the story of Griswold’s role in the development of a uniquely American art form.

The Ancestral Home

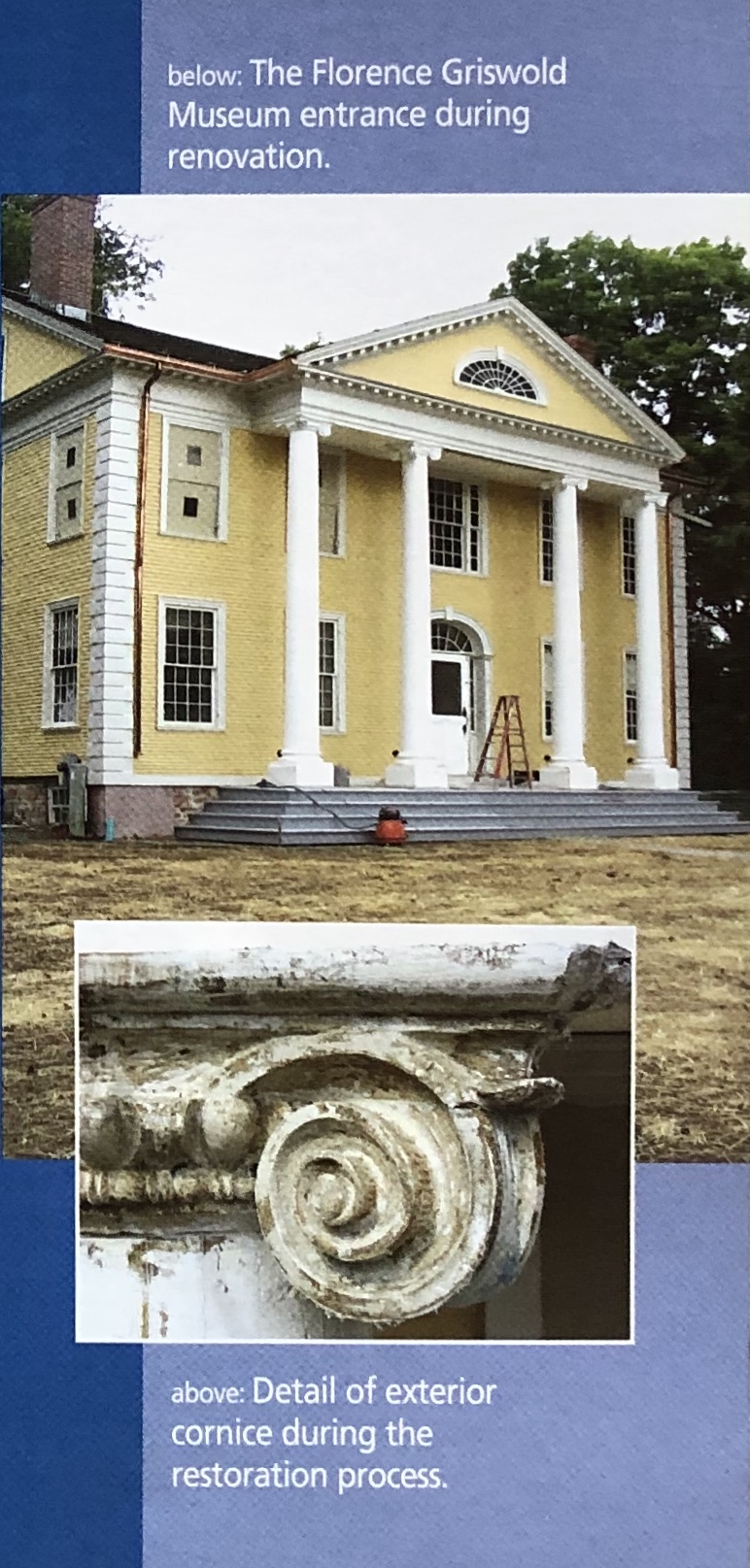

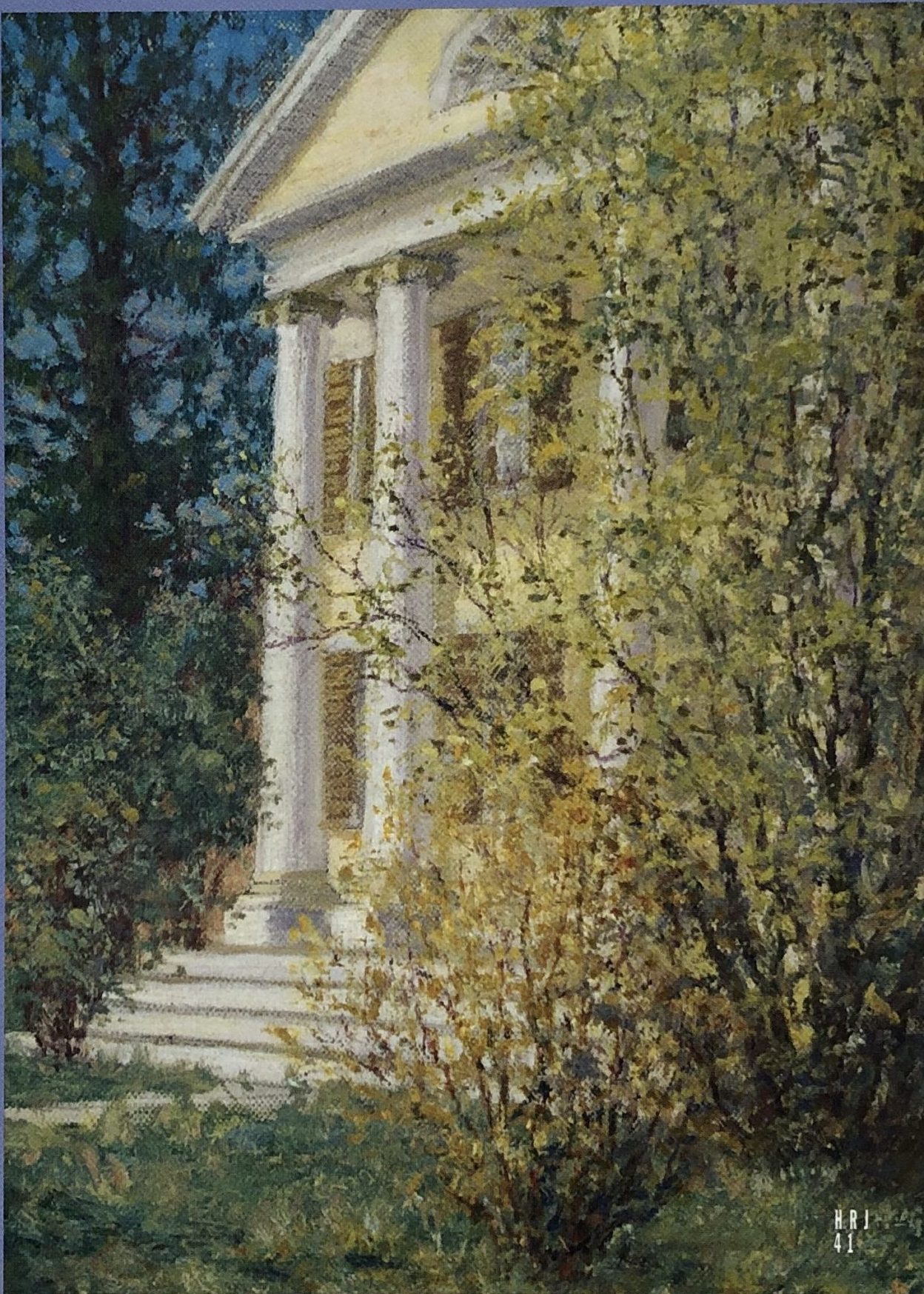

The Griswold House was built in 1817 for William Noyes by Samuel Belcher of Hartford Connecticut. Its design — featuring an impressive colonnaded front and pediment — blends Late Georgian and Federal architecture. Belcher also designed and built the Lyme Meeting House (1816 – 1817), now the Old Lyme Congregational Church (rebuilt in 1910 after a 1907 fire).(2)

Captain Robert Harper Griswold, a prominent packet boat captain for the Black X Shipping Line, purchased the home from the Noyes family in 1841. The town of Lyme, which includes present-day Old Lyme, was intertwined with the shipping trade, launching nearly 200 vessels from its shipyards between 1784 and the mid-1800s.(3) Captain Griswold and his wife Helen Powers took their place on Lyme Street, alongside other wealthy citizens.

Though Captain Griswold’s cross-Atlantic travels kept him away from his four children, Robert Jr., Helen Adele, Louisa, and Florence, Florence and her siblings enjoyed a privileged upbringing, including a good education and a well-appointed home with fine furnishings. This was all to change with the arrival of steam-powered vessels and the resultant decline in the use of sail. Captain Griswold retired in 1855 and unsuccessfully invested in local businesses such as the South Lyme Nail Factory. He was forced to sell some of his land and mortgage the rest.

With Captain Griswold’s failing health, it fell to the Griswold women (Robert Jr. died at 16 of diphtheria) to provide for the family. They opened the Griswold Home School in 1878 as a finishing school for young girls. The seeds of Florence’s boarding house for artists were sown during this period, as some students boarded at the house. The school closed in 1892, perhaps due to competition from the Boxwood School, another girls’ school in town(4), and hard times fell on Florence and her family. Louisa died in 1896, followed by their mother Helen in 1899. Florence and Helen Adele were left to care for the house, selling produce from their gardens, struggling to make ends meet. Helen Adele would, in subsequent years, be committed to the Hartford Retreat for the Insane (now the Institute for Living), where she died in 1913.

“It Looks Like Barbizon”

The arrival of the American painter Henry ward Ranger in 1899 turned Miss Florence’s fortunes around. Ranger had stayed the previous summer in East Lyme and was looking for a coastal town to start his own “American Barbizon” colony, referring to the French province in which a tonal style of painting, based on Dutch traditions, flourished. Ranger boarded with Miss Florence and fell in love with the local landscape. So enchanted was he with Old Lyme that he returned the following year with friends, commenting, “it looks like Barbizon, the land of Millet. See the gnarled oaks, the low rolling country. This land has been farmed and cultivated by men, and then allowed to revert back into the arms of Mother Nature. It is only waiting to be painted.”(5) Thus began the Lyme Art Colony, with an increasing number of artists coming to the boarding house each summer. A visit to Miss Florence’s boarding house often began with a written introduction. William Chadwick wrote in 1907, “Two of my friends, Mr. Spear and Mr. Crisp wish to spend a week or two sketching in Lyme. If they should come up with me on the twelfth of June would you have room for all three of us?”(6) Miss Florence, with a small domestic staff, provided for all of their needs. Art making was the primary focus, but there was still lots of time for horseshoes, canoe rides, and costumed parades through town.

A visit to Miss Florence’s boarding house often began with a written introduction. William Chadwick wrote in 1907, “Two of my friends, Mr. Spear and Mr. Crisp wish to spend a week or two sketching in Lyme. If they should come up with me on the twelfth of June would you have room for all three of us?”(6) Miss Florence, with a small domestic staff, provided for all of their needs. Art making was the primary focus, but there was still lots of time for horseshoes, canoe rides, and costumed parades through town.

The arrival of Childe Hassam in 1903 spurred a shift in the colony from the older tonal style of painting to an impressionist technique, characterized by bright colors and fast, broken brush strokes. As a relatively new style in America, Impressionism began to receive national attention, with its artists’ work gaining popularity early in the new century. Griswold’s artists were prolific, showcasing their work in the hall of her home, in local exhibitions at the Phoebe Griffin Noyes Library, and, by the 1920s, in more formal exhibitions at the Lyme Art Association, which still serves artists today.

Griswold’s artists provided her not only with a living as “keeper of the artist colony” (7) but also lifelong friendships — and a permanent legacy on the walls of her home. The artists painted panels throughout the house, initially on doors in the first floor’s main rooms and later on wood paneling installed in the dining room. Miss Florence treasured the works, and, despite later financial struggles, she refused to sell any of them.

Recreating the Boarding House

The Florence Griswold House’s current restoration arose out of years of research and two immediate needs. The first, and foremost, was the need to preserve the house itself. Years of ice damming, resulting from the third-floor attic’s conversion into a heated storage space, had caused damage to the roof and interior rooms. Outdated heating and cooling systems and older electrical wiring posed fire hazards. The discovery of extensive sill damage during the beginning stages of restoration also highlighted the need to preserve this 188-year-old landmark. With an estimated cost of more than $2 million, the restoration is generously supported at the federal and state level and by contributions from foundations and individuals.

Just as important as the physical restoration was the need to tell the museum’s story in a more compelling way. Like many historic house museums, the Florence Griswold Museum had struggled to choose which aspect of its long history to present to visitors. Previously, the historic rooms portrayed a confusing mix of periods, and as much attention was paid to the Griswold family as to Florence herself. Research and a scholarly colloquium yielded the recommendation that the interpretation focus on the boarding house for artists, with Miss Florence as a central figure. The year 1910 was chosen, a moment at which the art colony was at its zenith and, reported, at its most exclusive,”(8) with the established artists and Miss Florence deciding who was allowed to stay at the boarding house.

The house changed substantially around 1910. Miss Florence took out second and third mortgages and introduced indoor plumbing.(9) She had added dormers to the third floor, allowing her to let out rooms in the attic. Along with these improvements, the artists took it upon themselves to fix up the house’s central hall and parlor. Accounts of this refurbishing vary widely. Arthur Heming’s first-person account, “Miss Florence and the Artists of Old Lyme,” talks of extensive re-wallpapering, new carpeting, and reupholstery, while other accounts say that it was “more a question of very thorough cleaning and some painting.”(10) The work likely was done in secret as a surprise, and the artists hoped that Miss Florence would forgive them for taking “some liberties with the old house.”(11)

The house changed substantially around 1910. Miss Florence took out second and third mortgages and introduced indoor plumbing.(9) She had added dormers to the third floor, allowing her to let out rooms in the attic. Along with these improvements, the artists took it upon themselves to fix up the house’s central hall and parlor. Accounts of this refurbishing vary widely. Arthur Heming’s first-person account, “Miss Florence and the Artists of Old Lyme,” talks of extensive re-wallpapering, new carpeting, and reupholstery, while other accounts say that it was “more a question of very thorough cleaning and some painting.”(10) The work likely was done in secret as a surprise, and the artists hoped that Miss Florence would forgive them for taking “some liberties with the old house.”(11)

Among the research documents guiding the restoration is a Historic Structures Report. Completed in 2002, it analyzes the house’s structural history from 1817 to its current use as a museum in the 21st century.(12) The report found that the building’s basic footprint has barely changed since 1817, with the interior rooms remaining the same size and configuration. A historic paint analysis conducted by Brian Powell of Building Conservation Associates helped determine which of the many paint colors found on the exterior and interior are closest to what would have been used in 1910.

As seen from Lyme Street, the house’s newly restored facade looks strikingly altered: The front steps have been restored to their 1910 appearance, with four risers descending on either side and railings and signage removed. The clapboards are painted a rich, yellow-tan color. Additional features, including the tops and bases of the columns’ capitals, have been “picked out” in this color, differentiating them from the grayish-white trim, a detail documented in period paintings. This visually animates the facade as it did in the early years of the colony. Green shutters draw attention to the large windows. The side porch served as the main entryway for guests and visitors, and it will do so again when the house reopens. A restored lattice on the final bay of the side porch replicates an original element.

New technology is also being put in place to preserve the house into the future. Beyond the back ell of the house, a new mechanical shed has been constructed on the site of an old carriage shed. This building, not intended as a historic construction, houses all of the new environmental control systems, linked to 15 geothermal wells that will provide a “green,” environmentally-friendly means of heating and cooling the house.

A furnishing plan, written by historian Jackie Haley of Ridgefield, Connecticut using visual and written evidence from the site along with historic precedents, provides the framework for the interior restoration and reinterpretation. Restored historic rooms will feature reproduction floor and wall coverings, collection pieces, and the trappings of the artists, including paint brushes, cards, pipes, and drawings. New exhibits will highlight the house’s life as a boarding house and tell the story of the art colony.

The House Restored: A Visitor’s-Eye View

With the restoration completed, visitors to the Florence Griswold Museum will step back in time to 1910. Entering the “Holy House” from the side porch, the visitor steps into the wide center hall, which is crowded with chests of drawers, couches, and chairs. Artists refurbished the hall in 1910, adding grass-cloth wall covering (reproduced for the restoration) to hide imperfections in the plaster walls and provide a neutral backdrop for paintings displayed for sale. The hall was the busiest room in the house, with artists coming and going, taking calls on the recently installed telephone, and hanging their paintings.

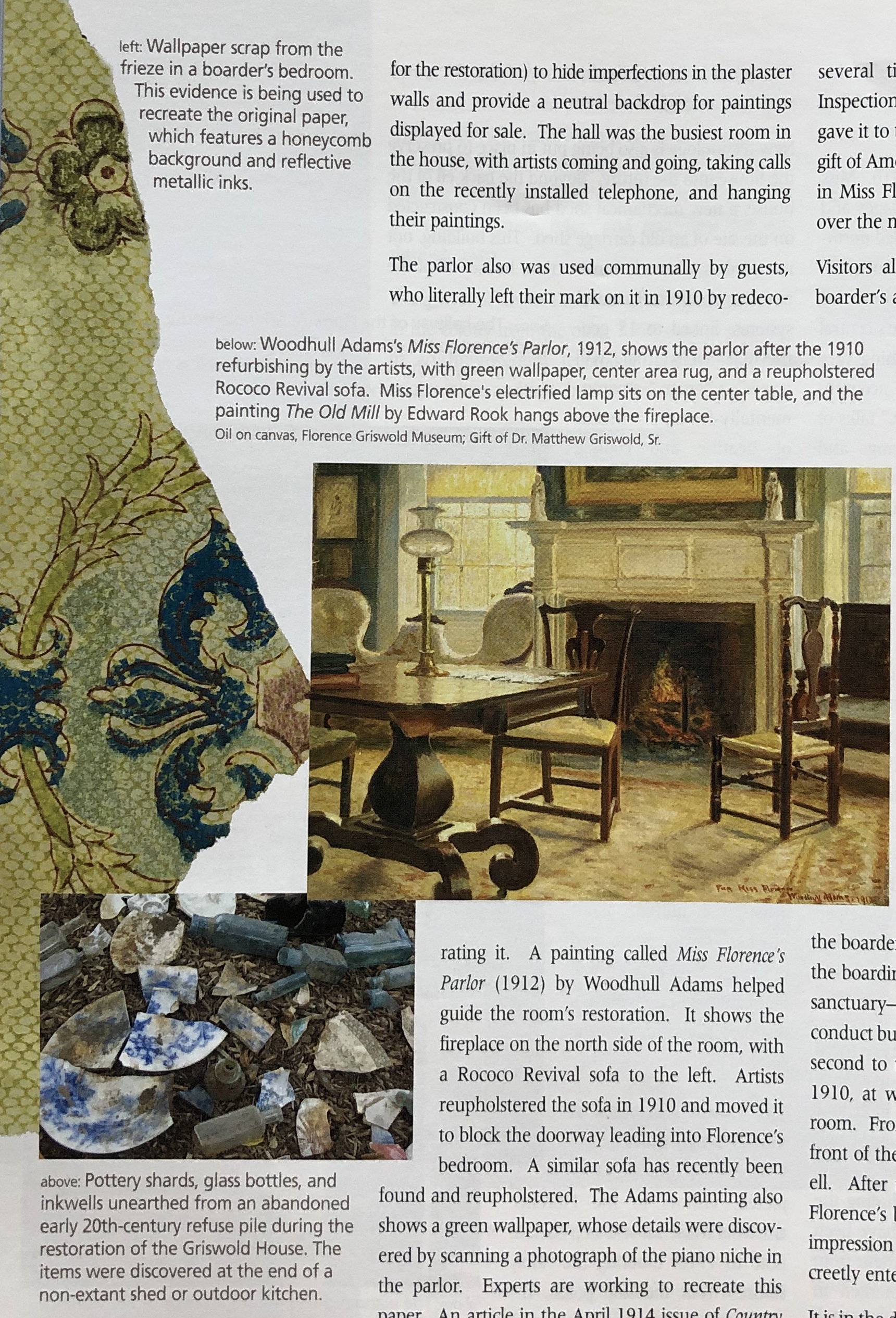

The parlor also was used communally by guests, who literally left their mark on it in 1910 by redecorating it. A painting called “Miss Florence’s Parlor” (1912) by Woodhull Adams helped guide the room’s restoration. It shows the fireplace on the north side of the room, with a Rococo Revival sofa to the left. Artists reupholstered the sofa in 1910 and moved it to block the doorway leading into Florence’s bedroom. A similar sofa has recently been found and reupholstered. The Adams painting also shows a green wallpaper, whose details were discovered by scanning a photograph of the piano niche in the parlor. Experts are working to recreate this paper. An article in the April 1914 issue of Country Life in America notes that over the white mantel hangs Edward F. Rook’s “The Old Mill,” with a dedication to Miss Griswold on the canvas. This painting, after leaving Florence’s home, changed hands several times until the Hartford Steam Boiler Inspection and Insurance Company acquired it and gave it to the museum in 2002 as part of their larger gift of American art. Modern-day visitors, like those in Miss Florence’s time, will see the work hanging over the mantel.

The parlor also was used communally by guests, who literally left their mark on it in 1910 by redecorating it. A painting called “Miss Florence’s Parlor” (1912) by Woodhull Adams helped guide the room’s restoration. It shows the fireplace on the north side of the room, with a Rococo Revival sofa to the left. Artists reupholstered the sofa in 1910 and moved it to block the doorway leading into Florence’s bedroom. A similar sofa has recently been found and reupholstered. The Adams painting also shows a green wallpaper, whose details were discovered by scanning a photograph of the piano niche in the parlor. Experts are working to recreate this paper. An article in the April 1914 issue of Country Life in America notes that over the white mantel hangs Edward F. Rook’s “The Old Mill,” with a dedication to Miss Griswold on the canvas. This painting, after leaving Florence’s home, changed hands several times until the Hartford Steam Boiler Inspection and Insurance Company acquired it and gave it to the museum in 2002 as part of their larger gift of American art. Modern-day visitors, like those in Miss Florence’s time, will see the work hanging over the mantel.

Visitors also will see, for the first time, a typical boarder’s accommodations. A former parlor on the first floor was converted into a bedroom. Henry Ward Ranger stayed for a time in this room, as did Woodrow and Ellen Axson Wilson on one of their many visits. This room was not among those refurbished by artists, and by 1910 it still retained its grand wall-to-wall carpeting, family heirlooms, and patterned wallpaper. Wallpaper scraps, discovered during a 1982 remodeling, are guiding wallpaper expert Laura McCoy of Stratford, Connecticut as she recreates this colorful paper. This wall treatment, and the others in the restoration, will be a vast change from the white walls that have been the norm for years in the historic rooms of the house.

Miss Florence’s restored bedroom will provide a compelling comparison to the boarders’ room. Though situated in the midst of the boarding house, Miss Florence’s bedroom was a sanctuary — but one from which she could easily conduct business. She moved her bedroom from the second to the first floor, close to the main hall, in 1910, at which time she added an adjacent bathroom. From there, she attended to boarders in the front of the house and to domestic staff in the back ell. After the restoration, the main doors to Miss Florence’s bedroom will be closed, maintaining the impression of a private chamber; visitors will discreetly enter the room through a converted closet.

Harry Hoffman’s “View of the Griswold House”, 1908, shows the “picked out” color of the capitals and bases of the columns. Oil on canvas, Florence Griswold Museum, GIft of the Family of Mrs. Nancy B. Krieble

It is in the dining room, at the culmination of the visitor’s journey into life at the boarding house, that the legacy of Miss Florence and the artists of the Lyme Art Colony are best illustrated. Mustard colored plaster will provide a rich backdrop for the original artist-painted panels and wood trim. These panels are a testament to the artistic talent of the American Impressionists and to the camaraderie they shared. The restored dining room will feature two original dining tables, recently reacquired, as well as a recreated emblem on the fireplace bricks. This imaginative and fanciful heraldic crest represents “The Knocker’s Club,” a group of artists who gathered together to critique or “knock” each other’s work.

Miss Florence’s presence, and that of her boarders, has been felt throughout the restoration. One recent morning, digging at the construction site unearthed a forgotten refuse pile with shards of ceramics, intact bottles, inkwells, and other personal effects. The backhoe’s loud engine ceased for a few hours, and the artifacts were carefully pulled from the earth., each one a reminder that the grounds of the museum are alive with history. WIth the reopening of the house, a new generation of visitors will be welcomed to “a home in the true sense,” the place that inspired American Impressionism.

Research Associate Liz Farrow is coordinating the refurnishing of the Florence Griswold House.

Explore!

The Florence Griswold Museum

96 Lyme Street, Old Lyme

The museum sits on 11 acres along the Lieutenant River. In addition to the original 1817 Griswold House, the museum features a riverfront gallery with changing art exhibitions, an education center, historic gardens, and a restored art studio. The museum is open year-round. For additional information call (860) 434-5542 or visit www.flogris.org.

“’Only waiting to be painted’: The Inspirational Landscape of Old Lyme,” Summer 2006

Grating the Nutmeg

Episode 36: Fidelia Bridges’s Connection to Old Lyme & A Ride on the Air Line Trail

Footnotes

1 Woodrow Wilson to Mary Peck, July 25, 1901, Link et al, eds. The Papers of Woodrow Wilson, p. 318.

2 David Dangremond. “The Enigmatic Samuel Belcher”: A Preliminary Report, undated draft, Lyme Historical Society (LHS) Archive.

3 Laurie Bradt. “Keeper of the Artist Colony”: The Life of Florence Griswold (1850 – 1937), 2002, P. 5, unpublished manuscript, LHS Archive.

4 Bradt, p. 8.

5 New Haven Morning Journal and Courier, July 5, 1907.

6 Letter from William Chadwick to Florence Griswold, June 5, 1907, Florence Griswold Papers, LHS Archive.

7 Calendar Entry by Florence Griswold, October 11, 1911, LHS Archive.

8 Gregory Smith, “Notes on the Florence Griswold House,” Lyme Art Association (LAA) Papers, LHS Archive.

9 Mortgage deed, Florence Griswold to the Savings Bank of New London, 1910, probate records, Vol. 1, pg. 632, Lyme Land Records, LHS Archive.

10 Arthur Heming, Miss Florence and the Artists of Old Lyme, Pequot Press in association with LHS – Florence Griswold Association, Inc., 1971 and WIll Howe Foote, “Notes from conversation,” LAA Papers, LHS Archive.

11 Letter from Lewis Cohen to Florence Griswold, c. 1910, Florence Griswold Papers, LHS Archive.

12 The Historic Structures report includes an exhaustive year-by-year look at the house, researched and written by Rosemary Ballard-Boak.

13 Letter from Allen Talcott to Florence Griswold, Thanksgiving Day, 1901, Florence Griswold Papers, LHS Archive.