Patsie Fusco’s saloon, 526 Front Street on the corner Talcott Street, 1912. Connecticut Women’s Suffrage Association, State Archives, Connecticut State Library

By Gergely Baics

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Winter 2003

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

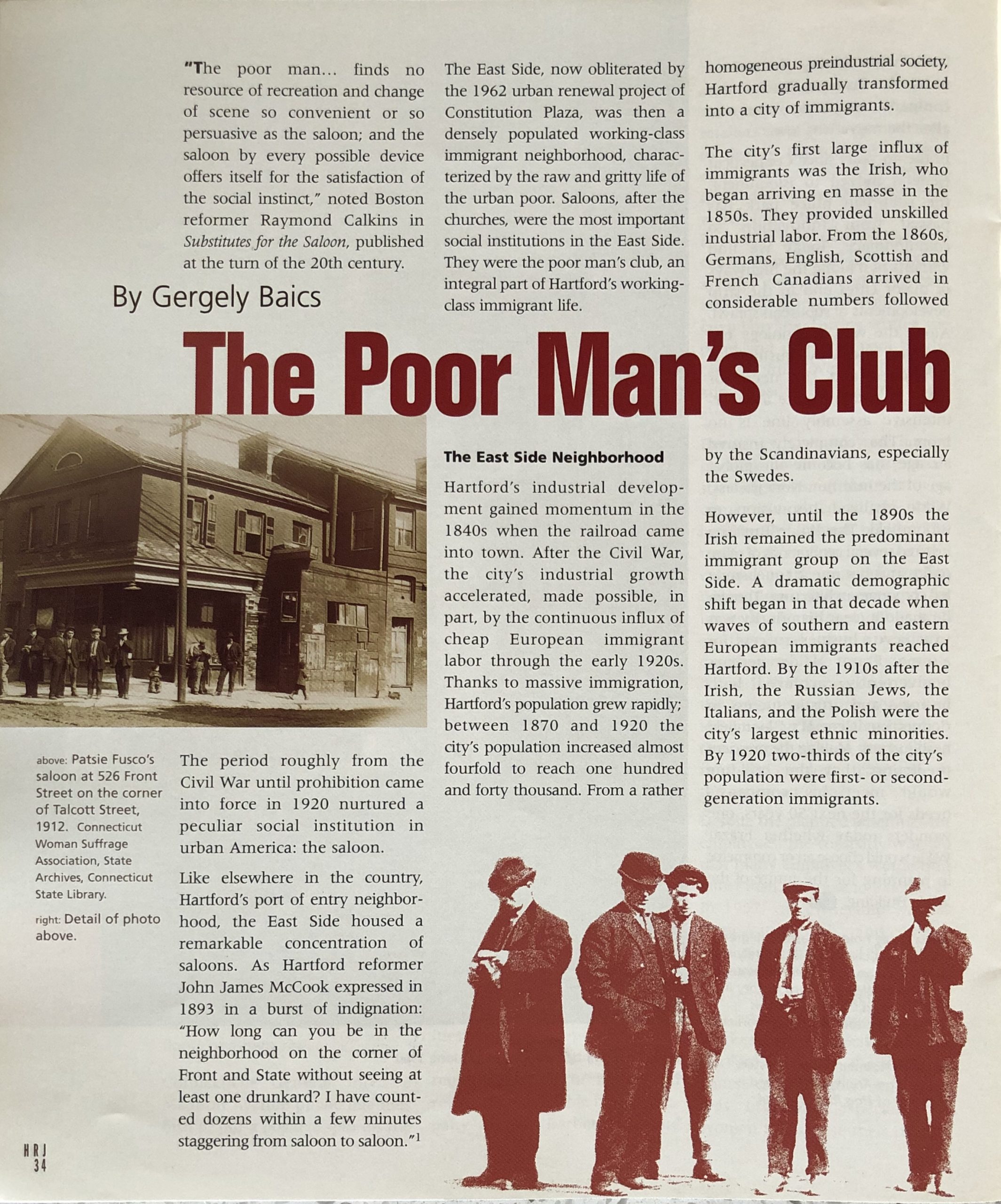

The poor man…finds no resource of recreation and change of scene so convenient or so persuasive as the saloon; and the saloon by every possible device offers itself for the satisfaction of the social instinct,”

noted Boston reformer Raymond Calkins in Substitutes for the Saloon, published at the turn of the 20th century. The period roughly from the Civil War until prohibition came into force in 1920 nurture a peculiar social institution in urban America: the saloon.

Like elsewhere in the country, Hartford’s port of entry neighborhood, the East Side, hosted a remarkable concentration of saloons. As Hartford reformer John James McCook expressed in 1893 in a burst of indignation: “How long can you be in the neighborhood on the corner of Front and State without seeing at least one drunkard? I have counted dozens within a few minutes staggering from saloon to saloon.”(1) [See “Had too Much,” Spring 2004.] The East Side, now obliterated by the 1962 urban renewal project of Constitution Plaza, was then a densely populated working-class immigrant neighborhood, characterized by the raw and gritty life of the urban poor. Saloons, after the churches, were the most important social institutions in the East Side. They were the poor man’s club, an integral part of Hartford’s working-class immigrant life.

The East Side Neighborhood

Hartford’s industrial development gained momentum in the 1840s when the railroad came to town. After the Civil War, the city’s industrial growth accelerated, made possible in part by the continuous influx of cheap European immigrant labor through the early 1920s.Thanks to massive immigration, Hartford’s population grew rapidly; between 1870 and 1920 the city’s population increased almost fourfold to reach 140,000 people. From a rather homogeneous preindustrial society, Hartford gradually transformed into a city of immigrants.

The city’s first large influx of immigrants was the Irish, who began arriving en masse in the 1850s. They provided unskilled industrial labor. From the 1860s, Germans, English, Scottish, and French Canadians arrive in considerable numbers, followed by the Scandinavians, especially the Swedes.

However, until the 1890s the Irish remained the predominant immigrant group on the East Side. A dramatic demographic shift began in that decade when waves of southern and eastern European immigrants reached Hartford. By the 1910s after the Irish, the Russian Jews, the Italians, and the Polish were the city’s largest ethnic minorities. By 1920 two-thirds of the city’s population were first-or second-generation immigrants.

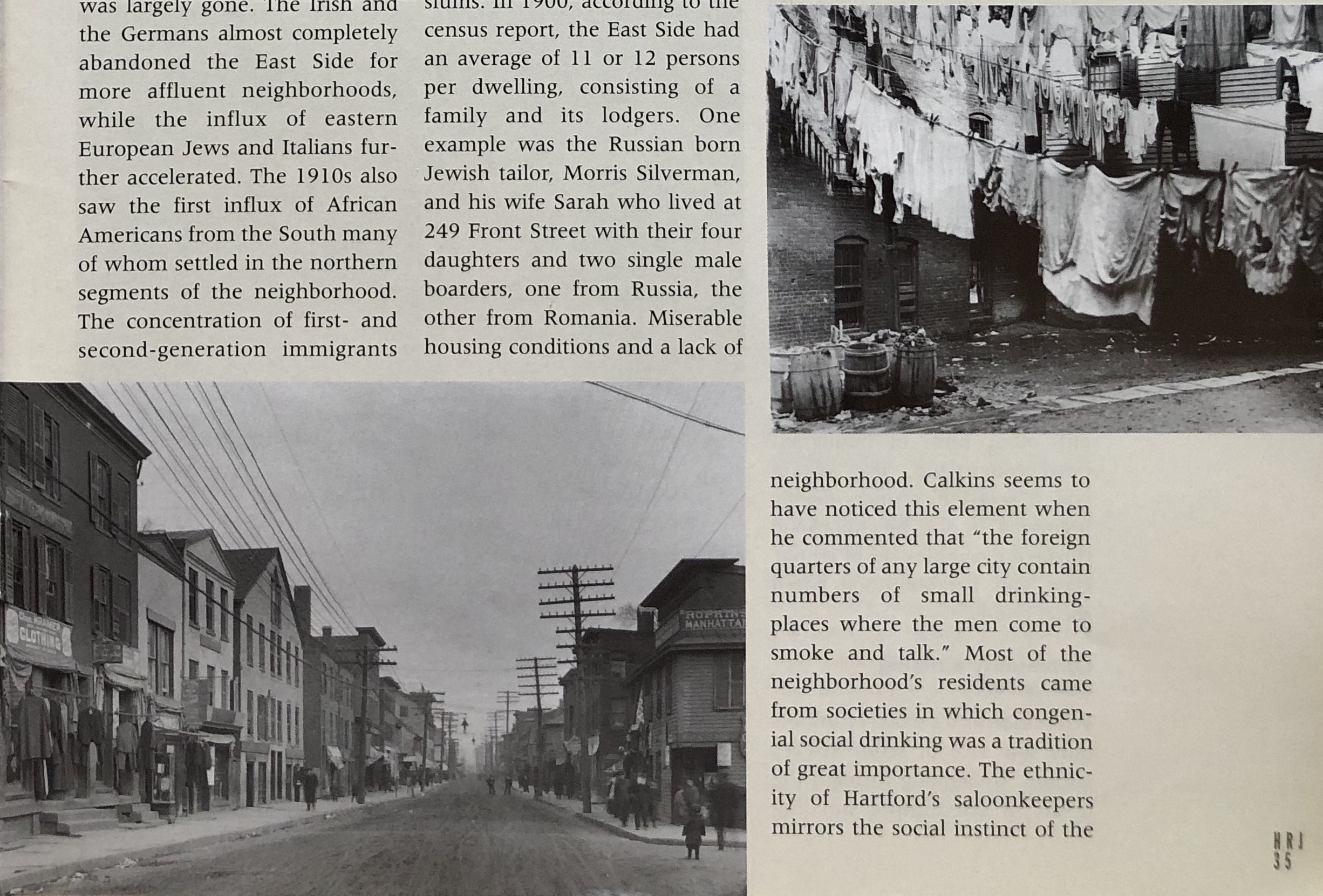

The concentration of immigrants in Hartford was unparalleled in the neighborhood that lay between Main Street and the Connecticut River: the East Side. Snapshots of Front Street, the axis and heart of the East Side, give an accurate picture of the settlement patterns of the East Side immigrants. The southern part of Front Street had a large Irish population living among Germans, Italians, Austrians, Hungarians, Russians, Scandinavians, and Romanians. The heart of the East Side was home to the Italians and the Russians. Further north was the city’s Russian Jewish enclave. Yet by 1910, the multiethnic character of the neighborhood was largely gone. The Irish and Germans almost completely abandoned the East Side for more affluent neighborhoods, while the influx of eastern European Jews and Italians further accelerated. The 1910s also saw the first influx of African Americans from the South, many of whom settled in the northern segments of the neighborhood. [See “Southern Blacks Transform Connecticut,” Fall 2013.] The concentration of first- and second-generation immigrants in the East Side reached its peak in the late 1910s; by 1920 about 90 percent of the East Side’s little more than 21,000 residents were foreign born or of foreign parentage.

left: Front Street, 1906. Jewish Historical Society of Greater Hartford; right: Rear yards on the East Side, 1912. Connecticut Woman Suffrage Association, State Archives, Connecticut State Library

The East Side was notorious for its terrible housing conditions. McCook noted in 1893 that “hardly more than a stone’s throw from one principal thoroughfare the alert eye can see sights not surpassed and not often equaled by what takes place in darkest New York.”(2) Overcrowding, filthy and unsanitary conditions, and the pervasive darkness of the tenements were the most often cited evils associated with living in the East Side slums. In 1900, according to the census report, the East Side had an average of 11 or 12 persons per dwelling, consisting of a family and its lodgers. One example was the Russian born Jewish tailor, Morris Silverman and his wife Sarah who lived at 249 Front Street with their four daughters and two single male boarders, one from Russia, the other from Romania. Miserable housing conditions and a lack of privacy at home drove the poor laboring man to seek relief in the East Side saloons. As Jacob Riis pointed out in his now classic How the Other Half Lives, “in many a tenement-house block the saloon is the one bright and cheery and humanly decent spot to be found….within its doors only is refuge, relief.”

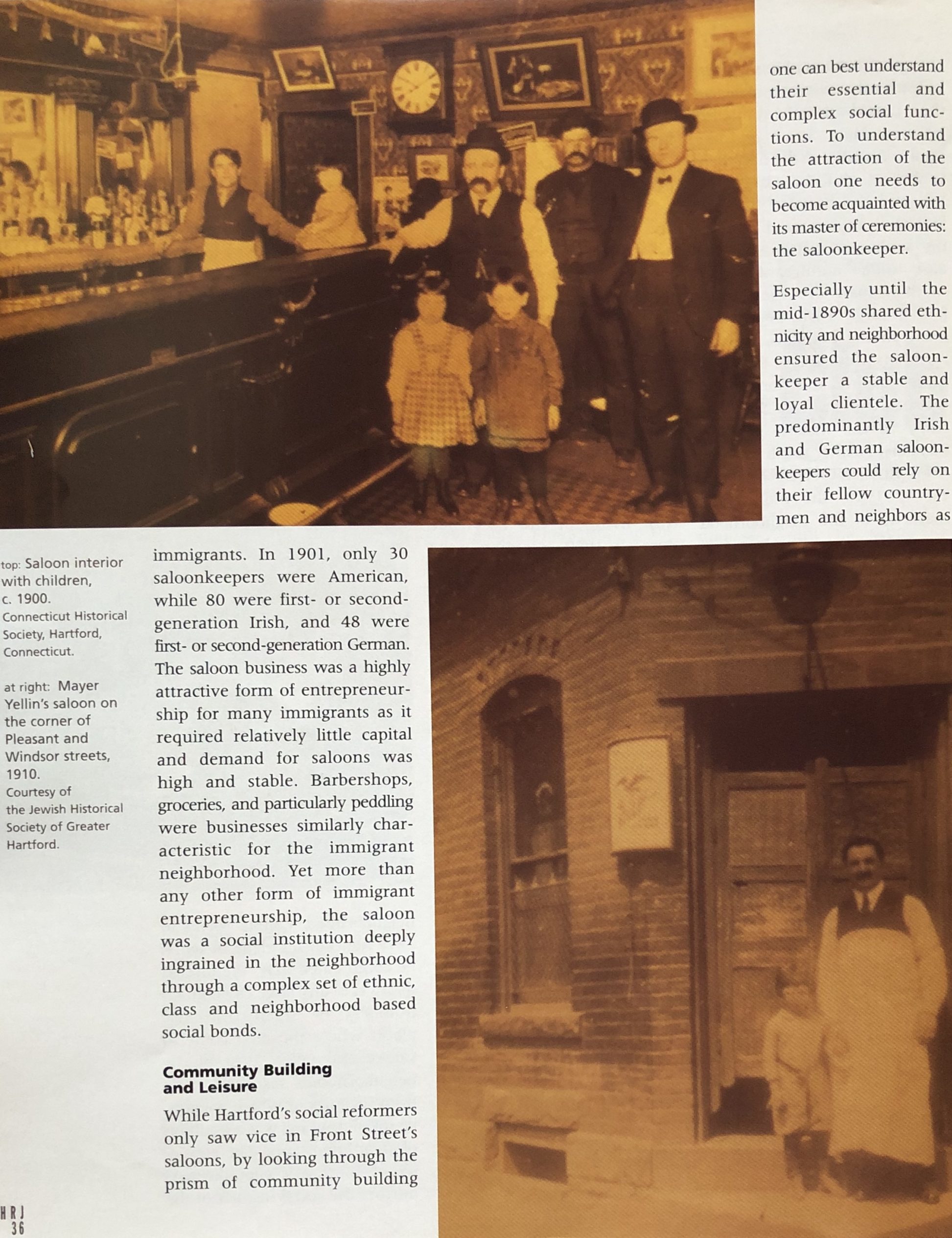

Around the turn of the century the East Side was home to a little less than one quarter of the and city’s population but housed nearly half of the city’s saloons, numbering between 170 and 180.(3) Besides working-class status, the cultural factor is just as important in explaining the exceptionally high demand for saloons in the neighborhood. Calkins seems to have noticed this element when he commented that “the foreign quarters of any large city contain numbers of small drinking-places where the men come to smoke and talk.” Most of the neighborhood’s residents came from societies in which congenial social drinking was a tradition of great importance. The ethnicity of Hartford’s saloonkeepers mirrors the social instinct of the immigrants. In 1901, only 30 saloonkeepers were American, while 80 were first- or second-generation Irish, and 48 were first- or second-generation were German. The saloon business was a highly attractive form of entrepreneurship for many immigrants as it required relatively little capital and demand for saloons was high and stable. Barbershops, groceries, and particularly peddling were businesses similarly characteristic for the immigrant neighborhood. Yet more than any other form of immigrant entrepreneurship, the saloon was a social institution deeply ingrained in the neighborhood through a complex set of ethnic, class, and neighborhood based social bonds.

Community Building and Leisure

While Hartford’s social reformers only saw vice in Front Street’s saloons, by looking through the prism of community building one can best understand their essential and complex social functions. To understand the attraction of the saloon one needs to become acquainted with its master of ceremonies: the saloonkeeper.

Especially until the mid-1890s shared ethnicity and neighborhood ensured the saloonkeeper a stable and loyal clientele. The predominantly Irish and German saloonkeepers could rely on their fellow countrymen and neighbors as their patrons. Until the 1890s saloonkeepers usually lived on the premises or nearby. Later many saloonkeepers moved their residences out of the East Side but maintained their profitable enterprises in the neighborhood.(4) The mounting price of a saloon license by the turn of the century and the costs associated with the saloons’ increasingly sophisticated services hindered the entry of newly arrived Italians and the eastern European Jews into the saloon business, thus somewhat weakening the neighborhood and ethnic bonds.

The saloonkeeper’s personality also mattered a great deal. A good saloonkeeper was a cultural magnet for the community. Calkins described him as above all a “man of the people. He knows his men and knows them well. He knows often about their families and their circumstances, and thus has a hold on their sympathies.” The saloonkeeper’s qualities were essential to turning the saloon into the center of the local information network, the place to learn about new hiring, local matters and politics, or simply read some free newspapers. Saloons also offered a remarkable diversity of services. They functioned as the neighborhood’s post office, the poor man’s bank, and informal labor bureaus. Open from early in the morning until midnight, saloons provided shelter, public toilets, and free food. For the price of a drink patrons could help themselves to a variety of free food displayed at the bar, food many of the city’s poor depended on. When in 1913, due to a tuberculosis epidemic the free lunch was outlawed, one of the patrons who fell sick argued that without the saloon’s free lunch authorities would have “to build two more shacks to accommodate the men who would be driven in by the inability to get food.”(5)

The saloonkeeper’s personality also mattered a great deal. A good saloonkeeper was a cultural magnet for the community. Calkins described him as above all a “man of the people. He knows his men and knows them well. He knows often about their families and their circumstances, and thus has a hold on their sympathies.” The saloonkeeper’s qualities were essential to turning the saloon into the center of the local information network, the place to learn about new hiring, local matters and politics, or simply read some free newspapers. Saloons also offered a remarkable diversity of services. They functioned as the neighborhood’s post office, the poor man’s bank, and informal labor bureaus. Open from early in the morning until midnight, saloons provided shelter, public toilets, and free food. For the price of a drink patrons could help themselves to a variety of free food displayed at the bar, food many of the city’s poor depended on. When in 1913, due to a tuberculosis epidemic the free lunch was outlawed, one of the patrons who fell sick argued that without the saloon’s free lunch authorities would have “to build two more shacks to accommodate the men who would be driven in by the inability to get food.”(5)

The information network of the saloons served the East Side’s ethnic charities and labor unions as well. Many of these organizations capitalized on the saloonkeeper’s experience with financing and their willingness to provide free meeting space. Saloonkeeper James F. Lawler, the treasurer of the Bricklayers and Plasters Union, hosted regular meetings at his saloon at 32 Front Street.(6)

Saloon keeping could also be turned into important political capital. Many saloonkeepers, especially those of Irish origin, used saloons as stepping-stones to enter local politics. One such person was Thomas Monahan, a respected member of two Irish organizations–the Ancient Order of Hibernians and the Knights of St. Patrick — who served two terms as alderman for one of the East Side wards from the late 1870s to the early 1880s.(7)

Yet the East Side saloon was above all a social place for working-class men; women were not welcome. In the poor man’s club flourished a culture that meant a refuge from both the workplace and from the home. Jack London described it generally in John Barleycorn: Alcoholic Memoirs: “life was different. Men talked with great voices, laughed great laughs, and there was an atmosphere of greatness.” Saloon culture was characterized by its peculiar “internal democracy,”(8) which strictly adhered to the principle of reciprocity that required patrons to engage in the treating rituals. Collective games, cards, bowling, and pool were also an element of socializing in a saloon. Sport events, especially prizefighting, were remarkably popular. The preferred drinks were whiskey, ale, porter, and above all, the German brew, lager. As for congenial socializing and leisure, there was no rival to the saloon: every night in the East Side the laboring men gathered to find relief.

The East Side Underworld

For the middle and upper classes however, saloons stood harshly at odds with traditional American morals and were blamed for many social disorders: skid row lifestyles, political bosses, and the most important the destruction of the sanctity of the home and the family. Although, critics like McCook no doubt exaggerated the “social evils” associated with the saloons, a faithful account must address the East Side “underworld.”

“The Police Court Column” of The Hartford Courant regularly reported arrests made for public drinking, suggesting that intemperance was most pervasive in the East Side. Stories such as that of an underage man named Brink were common matters in the East Side night. Brink, in a state of drunkenness, met Officer Keegan, the largest man on the police force, and called him names resulting in Officer Keegan fracturing Brink’s skill. More sadly, it was not uncommon for a laboring man to drink away his family’s budget.

McCook associated all social evils in Hartford–abused and abandoned children, homicide, vagabondage, pauperism, and venal voting (selling of votes for liquor or for money)–with the saloons. He noted that “the doors of the Hartford Almshouse were thrown wide open early in the morning of every election day, and that the inmates returned in the evening quite uniformly intoxicated.”(9) McCook’s vehement antisaloon sentiments certainly distorted his sense of objectivity. Yet, someone like the Irish ward politician Thomas Monahan, who was a brothelkeeper as well as a saloon owner, was probably not too shy to line up the city’s poor and buy their votes with a few bucks or a little booze.

Gangs also operated in the East Side. Most often they engaged in the so-called rolling schemes. Gang members hung out in a saloon waiting for an unsuspicious victim who they invited for ‘congenial’ drinking. When the poor fellow was drunk enough, someone carefully separated him from his money.(10)

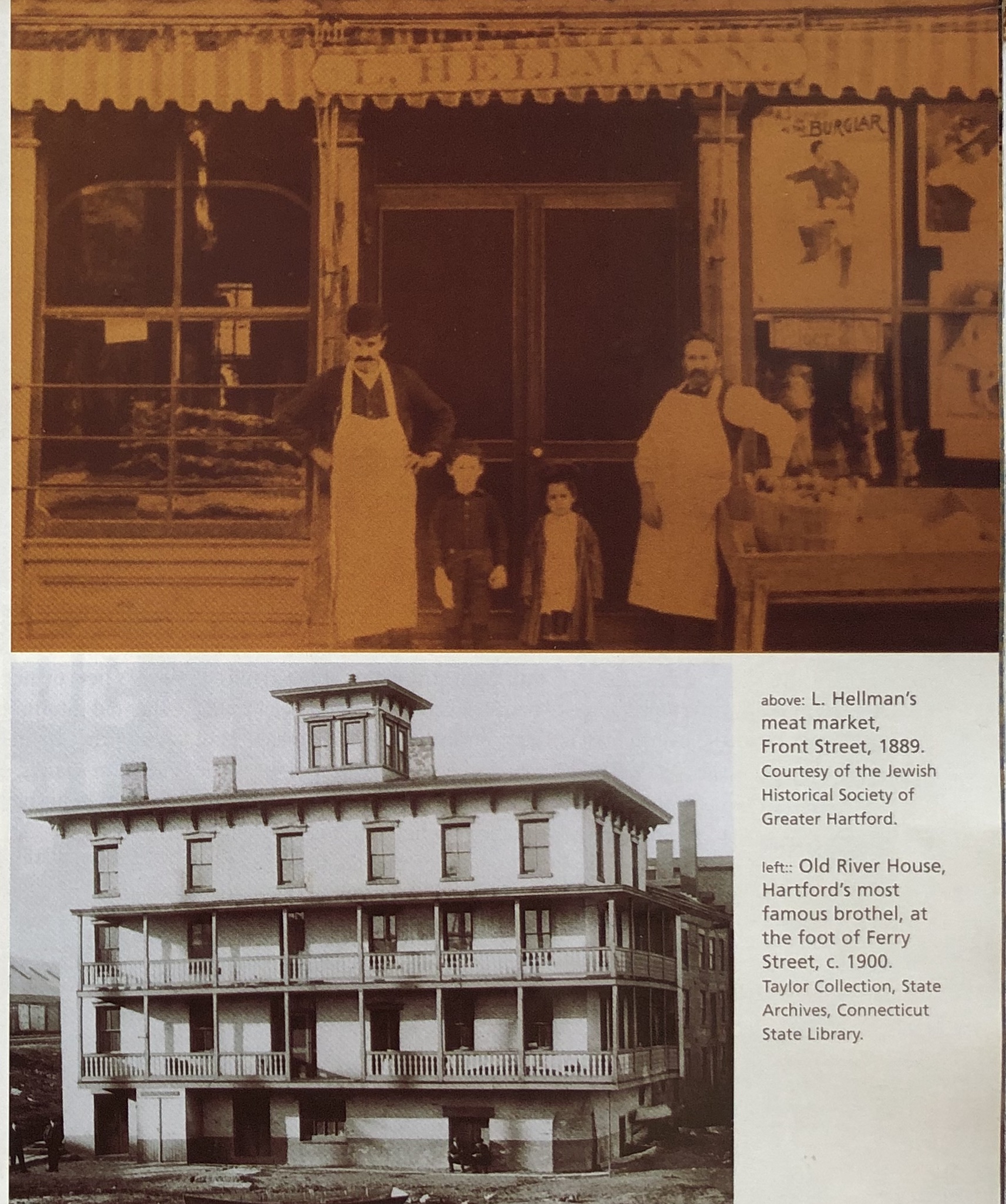

In Hartford, prostitution was generally tolerated until 1911. The Hartford Vice Commission Report that year stated that “liquor traffic and prostitution go hand in hand.” Yet, McCook’s findings show that only two out of the East Side’s 79 saloons were directly engaged in the commercial sex business at the turn of the century. Brothels in general were separate establishments from the saloons, although the great majority of brothels were located in the East Side, and some saloonkeepers did allow soliciting to take place on their premises.

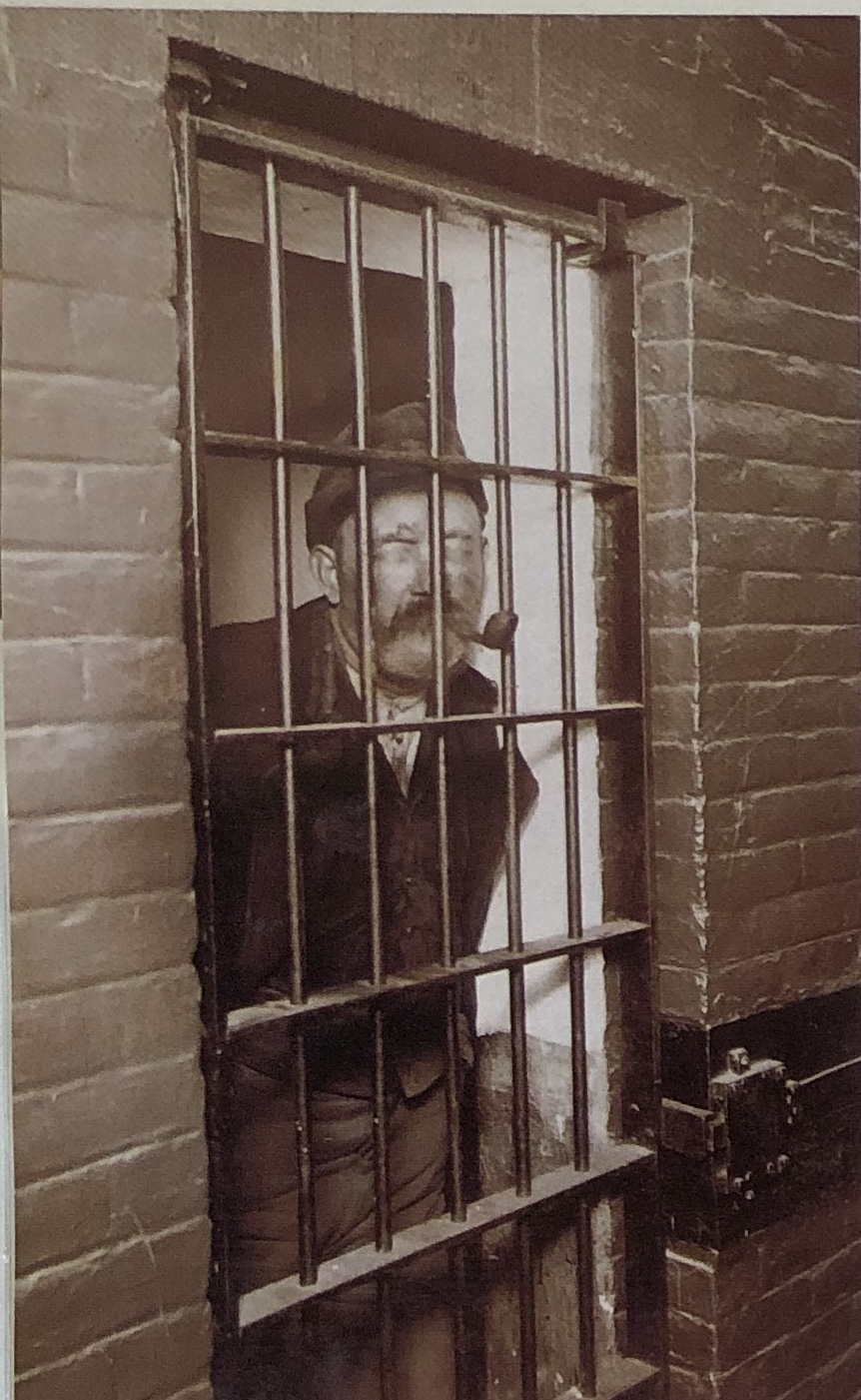

The famous Patsie Fusco versus Pasquale Pigniulo case in 1911, described in the Vice Commission Report, resulted in the city’s most comprehensive antiprostitution campaign. Fusco ran a well-known saloon at 526 Front Street. The place was also a so-called “fifty cents house,” which meant that for every visit the prostitute received twenty-five cents, while the other twenty-five cents went to Fusco. Pigniulo, an agent of the Bureau of Investigation of the United States Department of Justice, threatened to arrest Fusco on charges of white slave trade unless Fusco paid Pigniulo $500. Fusco had paid about $300 to Pigniulo when he learned that there was, in fact, no arrest warrant pending against him. He decided to report the shakedown to Detective Sergeant William Weltner of the Hartford Police. Weltner marked thirty $5 bills that Fusco was to give Pigniulo at Union Station. While the transaction was being performed, Weltner arrested Pigniulo on the charge of blackmailing. The ensuing public outrage, after the incident was reported in The Hartford Courant, demanded a termination of the policy of toleration of prostitution in Hartford.

Hartford’s reformers and the newspaper offer many fascinating stories of life in the saloons of the old East Side. Yet, one should never be misled by the antisaloon bias and suspicion that are manifest in these accounts. Intemperate drinking and crime were certainly a part of the East Side saloon life, but they were rather rare. For the average saloonkeeper, the reputation of his establishment was of great importance, something to protect, just as much as most saloon patrons were neither drunkards nor criminals.

Farewell to the Saloons

The remarkable popularity of the East Side saloon can be best explained by the complex relationship between the saloon and the local community. The saloon was the only affordable leisure for the working-class immigrant, but beyond that it offered services both for the individual and the wider community. The city’s elite was puzzled and felt threatened by the foreign world of the East Side slums: a world that just “a long stone’s throw” from City Hall nurtured a peculiar culture that stood at odds with white middle class morals and values. And indeed, some saloons were not innocent of fostering immoderate drinking or even certain forms of organized crime. Yet for Hartford’s immigrant laborer the saloon was an alternative to the world of market exchange, a place where he was worth more than his labor. The social bonds that manifested themselves in the saloons emphasized the core value of solidarity. In this sense the saloon was both a refuge and a source of self-organization for the East Side community until the 1920s. Unfortunately Prohibition (1920-1933), while failing in its intention of ending the American liquor trade, nevertheless succeeded in terminating one of the most important social spheres of Hartford’s immigrant working-class culture.

Gergely Baics was a Kellner scholar during the 2000-2001 academic year at Trinity College, where he researched and wrote about the immigrant culture and the saloon life of Hartford’ East Side, from which this article was taken.

(1) John J. McCook. “The Duty of a Hartford Citizen,” in The Social Reform Papers of John James McCook (1893) (Hartford: Trinity College Library), microfilm, reel 1, item 16, 14.

(2) Ibid, item 16, 13.

(3) Geer’s Hartford City Directory 1896. (Hartford: Hartford Printing Co, 1896.), 591-92; 1900, 705-6; 1905, 855-56.

(4) This analysis is based on the Geers directories’ listing of business and local residents’ addresses in a sequence of every five years (1870-71, 1875, 1879, 1885, 1890, 1896, 1900, 1905, 1909, 1914.)

(5) “Free Lunch Counter Breeds Consumption,” Hartford Courant, 24 March 1913.

(6) Geer’s Hartford City Directory 1890 (Hartford: Hartford Printing Co, 1890), 564.

(7) Geer’s Hartford City Directory 1875 (Hartford: Hartford Printing Co, 1875), 299; 1879, 278; 1885, 540; 1890, 576.

(8) Roy Rosenzweig, Eight Hours for What We Will. Workers and Leisure in an Industrial City, 1870-1920 (Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1983), 58-59.

(9) McCook, “The Alarming Proportion of Venal Voters,” in Published Writings: The Social Reform Papers of John James McCook (1892) (Hartford: Trinity College Library), microfilm, reel 7, item 2, 9-13.

(10) “Gangs of Today and Yesterday in Hartford,” Hartford Courant, 8 February 1914.