(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. SPRING 2008

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

A large, wicker balloon basket in the New England Air Museum in Windsor Locks, Connecticut is believed by the museum to be the oldest surviving, intact aeronautical artifact used in the United States. This basket is a relic of the adventurous career of Connecticut inventor and showman Silas Markham Brooks, whose career as a balloonist reached great heights before he plummeted to obscurity in old age. With 187 known balloon ascensions, this man is arguably Connecticut’s foremost air traveler of the 19th century.

By the mid-1800s ballooning had progressed from brief, low-altitude flights of the crude, hot-air type invented by the Montgolfier brothers of France in 1783 to more sustained flights in gas-filled balloons. Municipal lluminating gas produced from coal was the least expensive option but was not always readily available. When municipal illuminating gas was unavailable, balloonists generated pure hydrogen gas from iron or zinc filings, water, and sulfuric acid, a laborious and expensive process.

The Brooks basket was formerly displayed at the Canton Historical Museum, which has a cache of Brooks-related memorabilia. For years the material languished in a locked safe; in 1997 museum staff opened the safe and discovered its contents. Inside was an old scrapbook of news clippings, several periodicals with articles on ballooning, and four packets of penciled notes (possibly an interview of Brooks by a Hartford Courant reporter, c. 1897) recounting episodes in his life. His accounts of his ballooning experiences have been verified by newspaper accounts and historical society archives. Most of his earlier exploits are yet to be authenticated.

Brooks was born in Plymouth, Connecticut in 1824 to Willard Brooks, a clockmaker and farmer, and Maria Markham Brooks. As a young man he worked as a farmhand in nearby Burlington and then in a wooden-works clock factory in the same town. His education included the usual local district school plus two semesters at Bristol Academy, the private forerunner of a public high school. Always tinkering with mechanical gadgets and musical instruments, Silas said he was hired in 1850 by Phineas T. Barnum to invent fanciful musical instruments and mechanical stage effects for Barnum’s American Museum in New York City. Brooks reported that he worked for Barnum for a few months and then started his own career of entertaining the public.

A few years later, Brooks developed and managed a museum of curiosities in St. Louis, Missouri. Next, in partnership with two friends, he operated for a couple of years a traveling circus of 80 performers and 100 animals. To augment the shows, the partners hired the well-known balloonist John Wise to make public ascensions. The circus was successful, but the cost of generating hydrogen gas exhausted all the proceeds. Wise was the only one who profited, as he insisted on $100 in advance before each ascension.

Brooks next partnered with Samuel L. Brown, an old showman from Albany, New York, to stage balloon ascensions in the daytime and fireworks at night. In 1853, during a show in Memphis, Tennessee, their balloonist, William Paullin of Philadelphia, became ill and was unable to perform. Finding no one else to risk the flight, Brooks climbed into the basket slung beneath the hydrogen-filled balloon, cast off a few sandbags, and shot skyward. Reveling in the unaccustomed, spectacular view of the great Mississippi River, he floated along for several miles. Then, reluctantly, he released some of the gas from the balloon and descended to a bumpy and near disastrous landing.

Gas balloons of those days were made of silk panels that tapered together at both ends, stitched together, and coated with a varnish and linseed-oil mixture. The spherical or pear-shaped gas-bag was then loosely encased in a network of cotton cords that attached to a wooden ring around the balloon’s neck. Suspended from the ring was the wicker passenger car. A wooden panel at the top of the gas-bag had at its center a four-inch trapdoor held shut by a coil spring. A lanyard from this door led down through the balloon to the passenger car so that the operator could release gas to cause the balloon to descend. To ascend, the aeronaut spilled sand from a ballast bag to lighten the weight. Horizontal movement, as with today’s hot air balloons, depended on air currents.

Brooks’s unexpected balloon voyage was a defining experience that led to a new career for the young Yankee. He called himself “Professor Silas Brooks, the Great American Aeronaut.” (Balloonists of that day regularly dubbed themselves “Professor,” regardless of their education.) From then on, Brooks himself made all his own balloon flights.

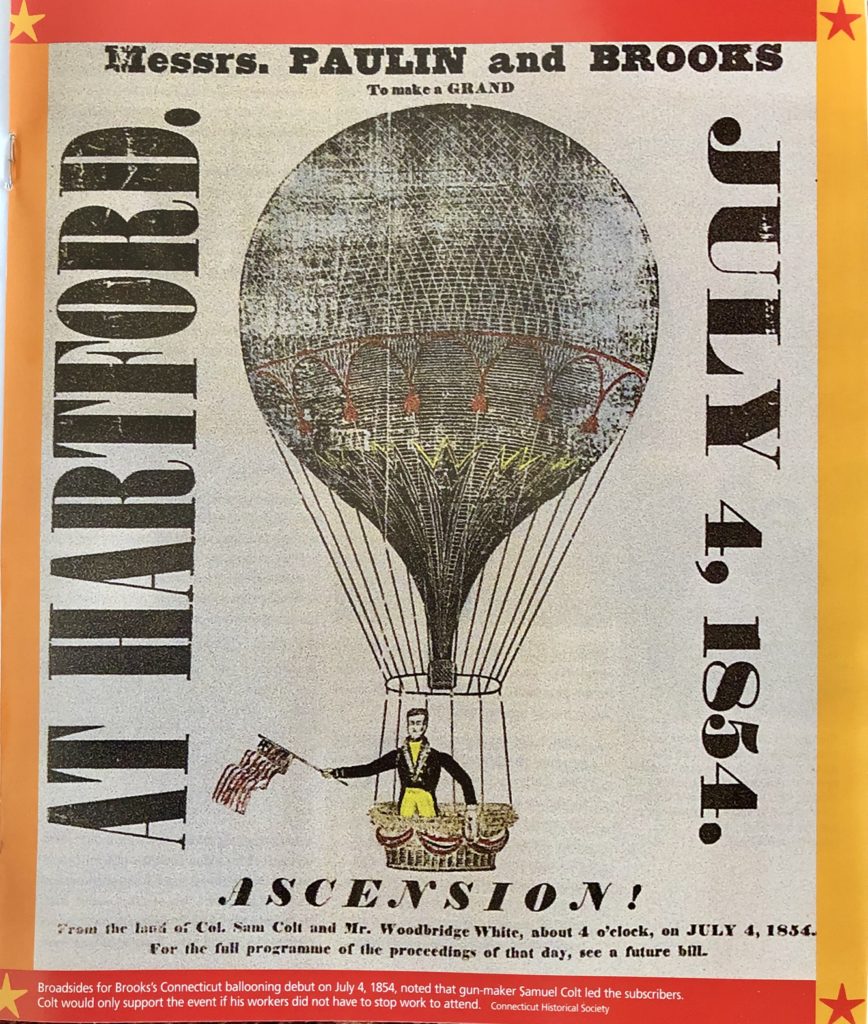

Brooks made his Connecticut ballooning debut in July 1854. Upon his arrival in the state, he went to see gun-maker Samuel Colt. In the packet of notes, Brooks reported why:

Colonel Colt was at that time building his immense dike on the flats below Hartford. I was told to see him first, for if his name headed the subscription list, the rest of the city would follow. I went to his office alone and rang the bell. A servant took in my card and came back to say that Colonel Colt would see me. When I entered his office he was sitting in his big armchair reading his newspaper and he hardly turned to look at me. “Any business with Colonel Colt?” said he. I replied— “Yes, I want to get up an aeronaut ascension by subscription and I was told to come to you first, for if you gave, the other people surely would.” He inquired when we wanted [to make the balloon ascension]. I replied, “June 25th.” “Won’t give you a cent,” was his answer—“Can’t afford to have my men stop work one day.” He added that he might consider it if the date were July 4th. (Colt’s workers would already have this national holiday off.)

Colt also offered $100 if Brooks and his colleagues would make the ascension from Colt’s meadow and promised further assistance in laying pipes from the city gas-works, putting up seats, and acting as marshal. The event was a great success, with laudatory accounts in the local papers the following day, and the aeronaut netted the very large sum of $1,600.

Brooks then went to Middletown to prepare for a flight in that city. He had his balloon spread out in a hall for inspection, but during the night the building caught fire and the balloon was lost. Undaunted, Silas hired several women to stitch panels together to make two new balloons and took his balloons to cities along the Ohio River.

The Midwest was great for ballooning because its abundance of wide-open farmland provided for safe landings. There was also a ready market of people willing to pay subscriptions to entice balloonists to perform. Teaming up again with Samuel L. Brown, “Professor” Brooks became a big success. He made the first balloon ascensions in several cities, including St. Louis and Chicago, and in the state of Michigan.

A heart-stopping incident occurred on Friday, September 17, 1858 in Centralia, Illinois. Brooks was not well that day, so a less-experienced man named Wilson made the ascension. After landing, Wilson left the balloon ropes in the hands of a group of men and boys. Thinking to have some fun with the tethered balloon, one man got into the basket and the ropes were loosened. However, he was too heavy, so his two children were placed in the basket and the ropes again loosened. With this lesser weight the balloon jerked free of the handlers, and the two children soared alone into the sky. Panic ensued. Brooks hurried to the scene to assure the parents that the balloon would come down eventually of its own accord. After a few hours, the resourceful eight-year-old girl noticed the small rope coming out of the neck of the balloon, tugged on it, and the balloon descended. They landed safely in a tree next to a farmhouse about 3 a.m. The October 1858 issue of Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper featured this escapade on its cover.

The following year Silas Brooks took part in a well-publicized attempt to build a balloon capable of crossing the Atlantic Ocean. A wealthy Vermonter, Oscar Gager, engaged John La Montain, another well-known aeronaut, to build a huge balloon capable of lifting 25,000 pounds, sufficient to carry all necessary equipment and passengers, including a boat for emergency ocean landing. They then hired John Wise, considered an authority on ballooning (he had flown balloons for Brooks’s circus earlier), to become the director-in-chief of the Trans-Atlantic Balloon Corporation. In 1850, Wise published a book on the scientific principles of ballooning, to which the aeronauts of the time often referred. (A copy of this book inscribed by the author “to my friend Silas M. Brooks” is in the collection of the Canton Historical Museum.) Wise decided on a test flight from St. Louis and persuaded the city to provide free city gas for the adventure. Silas Brooks volunteered to lead the way at the start in his smaller balloon, the Comet. On July 1 the two balloons took off. Silas descended at dusk, but the giant Atlantic went on for more than 800 miles and made a rough landing in upstate New York. The damaged balloon was used once more in a test flight, but again suffered damage, and the trans-Atlantic attempt was called off for lack of funds. Years later Wise was lost in a balloon flight over Lake Michigan.

Early in the Civil War, Brooks, Wise, and others offered their services to the Union, but aeronaut Thaddeus Lowe secured President Lincoln’s ear and became the founder of the Army Balloon Corps. Brooks and his younger brother George returned to Connecticut, where they made most of their remaining ascensions. Over the years Brooks taught others—including his brother and one Fred Moore—his craft. Brooks and Moore took a large balloon Brooks had built on a test flight from Winsted; they encountered a thunderstorm en route. In his notes Brooks described their adventure:

It seemed as if the balloon were drawn into the cloud to the very center. The edges of the cloud being like black curtains down around the balloon. It was dark; the balloon would whirl and sometimes almost turn bottom upwards. I adjusted my valve and tried to go up but so much water we could not rise. We were in the cloud and borne along with it, tossed by the currents in the cloud—up, down, cross-wise, everyway. Lightning went from one cloud to another with a snapping and crackling. The reverberations of the thunder would come up from below. We were drenched with sheets—hailstones hurled all around us. … I opened the valve as wide as I could to come down. As soon as we got below the cloud we struck a comparatively still atmosphere. We found ourselves pretty near the north end of New Hartford. It was not raining; the cloud went off over Hartford and gave them a terrible deluge. …Suddenly another current took us and wheeled us to the north and we landed on Barndoor Hills in Simsbury and came down in an old pasture lot and I tore the balloon open to let gas out but the wind caught the balloon and made a big sail. We tore through brush and rocks at a fearful rate. Finally we came up against a brush and stonewall fence. The basket caught the fence, a mangled, ragged, confused mass.

Looking for ways to make easy money, Silas hired an artist named Hilliard to paint a panorama depicting fanciful views above the clouds and aerial landscapes. Predecessors to motion pictures, panoramas consisted of long scrolls of cloth with painted scenes wound on large rollers. Wartime audiences in Connecticut and New York were lukewarm to the panorama’s focus on ballooning. Eventually the paintings were washed out and the cloth sold for bandages. Later, Brooks fared better with aerial photography: Some of the first aerial photographs in Connecticut were taken by news photographers from Brooks and Moore balloons over Hartford and Windsor.

About this time both brothers apparently established homes in Burlington and in October 1863 Silas Brooks married Harriet Beach, a circus equestrian from Terryville. Their only child, Henry, died of measles at age 18 months. Soon after, Harriet left Silas to rejoin a circus. He said she was fonder of horses than of him.

One night in 1864, Brooks was in the Marble Pillar Restaurant on Hartford’s Central Row, telling about how animals could be lowered from balloons by parachute. A Mr. Whiting offered him $50 if he would take Whiting’s dog up and release it safely by this means. Brooks accepted, offering Whiting another $50 if the adventure failed. Silas and George worked all night rigging up a harness and parachute; the next day, at about a mile high, they released the dog and chute. The dog landed safely. Two boys raced to the dog first and found a note offering $5 for its return to Mr. Whiting. That evening the Marble Pillar was filled to capacity with a crowd celebrating the dog’s return.

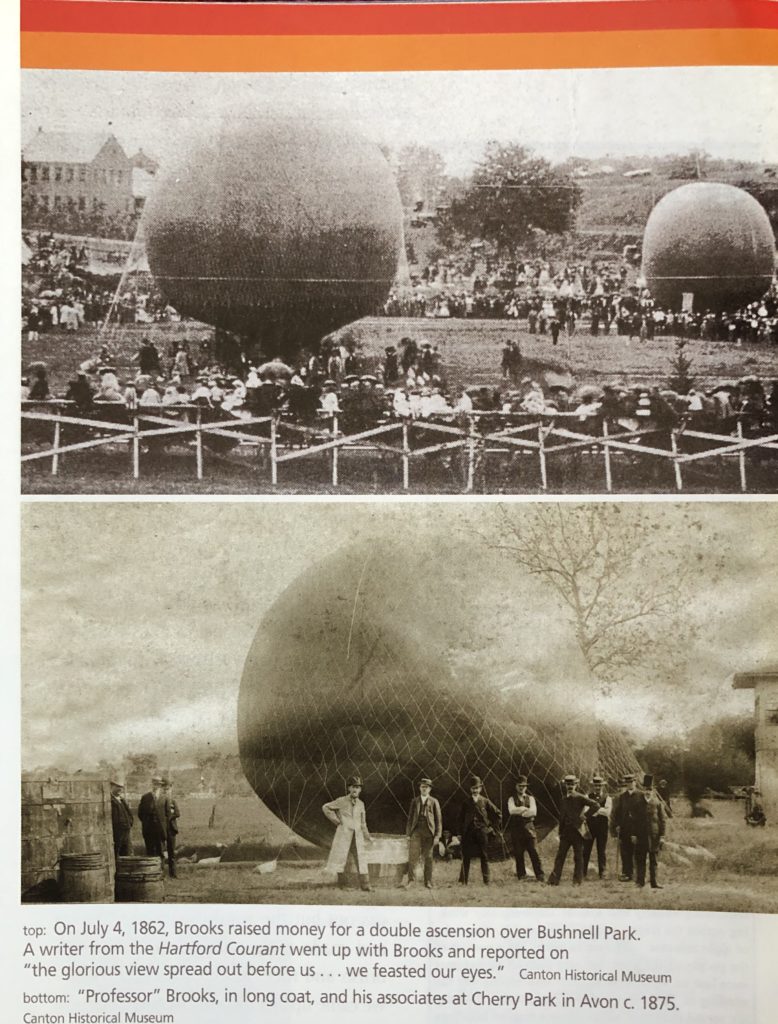

top: July 4, 1862. Canton Historical Museum

bottom: Brooks in long coat, Cherry Park, Avon, c. 1875. Canton Historical Museum

In the 1870s and 1880s balloon ascensions were frequently the feature attraction at fairs and holiday celebrations. Aeronauts like Brooks and Moore often earned extra cash by distributing advertising leaflets and flyers from the air. Most of the New England flights by the Brooks brothers were over short distances. The longest local flight that Silas made was from Cherry Park in Avon to Hubbardston, Massachusetts. Besides making many flights from Cherry Park, he went up from Meriden and Bushnell Park in Hartford.

Local hearsay has it that Silas Brooks in later life became addicted to alcohol, resulting in his making poor decisions and losing almost all his resources, including his Burlington home through foreclosure. There is evidence that he was fond of “ardent spirits”: he always celebrated his successful flights with large quantities of alcoholic drink and even admitted being drunk on at least one ascension. This may have led to a lessening of demand for further balloon performances.

Silas Brooks made his last ascension, from Hartford’s Bushnell Park, in 1894, when he was 70 years old. The Hartford Courant’s account was headlined “Gas Was Too Heavy, so the Balloon Ascension was a Ludicrous Failure.” Using municipal illuminating gas, which had variable lifting qualities, Silas barely got off the ground. Some men grabbed the basket and gave it a boost. It then bounced up into the branches of a tree on the west side of Trinity Street. After twisting and turning, it broke free, but it had been punctured, and gas was rapidly escaping. Then it hit a telephone wire and struck a home on Elm Street. People on the roof held the balloon while Silas was cut loose. Brooks was not seriously hurt, but it appears this ended his aeronautical career.

Late in the 1890s Brooks was seriously injured in Collinsville when an experiment he was conducting using naphtha, a volatile solvent, blew up—perhaps more evidence of Brooks’s increasingly impaired judgment. By the end of the century he was a ward of the Town of Burlington, living in the local poorhouse. Brooks died there in 1906 at age 82. A sister in New Haven was listed in his death notice as his only living relative; George had died at age 42 of tuberculosis. The Courant obituary concludes: “The funeral Saturday was a pathetic scene—made pathetic by the thought that this man whose going out was of so little consequence except to a very few had once been really great in the eyes of many. It takes no prophet to predict that briars will soon overgrow Brooks’s grave and that even the memory of his fame will be a forgotten story of the past.” This prediction sadly proved to be true until in December 1997 the Connecticut Lighter-Than-Air Society of hot-air balloonists dedicated a plaque in the Burlington Cemetery to “Silas Brooks, Connecticut’s First Balloonist.”

The Brooks balloon basket, years ago, was loaned to the Canton Historical Museum by descendents of P.F. Smith, a Collinsville hardware store proprietor who managed the Brooks balloon business in the 1880s. The owners of the basket later determined that it would receive more public exposure at the New England Air Museum and moved it there. That museum has assigned it a starring role in illustrating the history of mankind’s explorations and commercial and military exploitation of our atmosphere.

Explore!

The Canton Historical Museum, 11 Front Street, Collinsville. Hours vary seasonally. For more information call (860) 693-2793 or visit www.cantonmuseum.org.

The New England Air Museum, 36 Perimeter Road, Bradley International Airport, Windsor Locks, is open seven days a week. For more information call (860) 623-3305 or visit www.neam.org.