By Elizabeth J. Normen

(c) Connecticut Explored Winter 2017-2018

In 2005 a review copy of Henry Reed Stile’s History of Bundling, first published in 1869, came across my desk. My first impression was that it seemed like a funny topic to warrant a reprint—especially at $145.50 a copy. Its dedication, too, was curious.

I put the book aside, but this issue’s theme led me to pull it off the shelf and take a closer look.

I put the book aside, but this issue’s theme led me to pull it off the shelf and take a closer look.

It seems that after Stiles’s history of Windsor was published in 1859, Hayden wrote to him with strong objections to the assertion that after the French and Indian War Windsor’s soldiers had come home with

stores of loose camp vices and recklessness, which soon flooded the land with immorality and infidelity. The church was neglected, drunkenness fearfully increased, and social life was sadly corrupted. Bundling—that ridiculous and pernicious custom which prevailed among the young to a degree which we can scarcely credit—sapped the fountain of morality and tarnished the escutcheons of thousands of families.

Hayden feared “that this subject of bundling cannot be ventilated without endangering the fair fame of old Connecticut.”

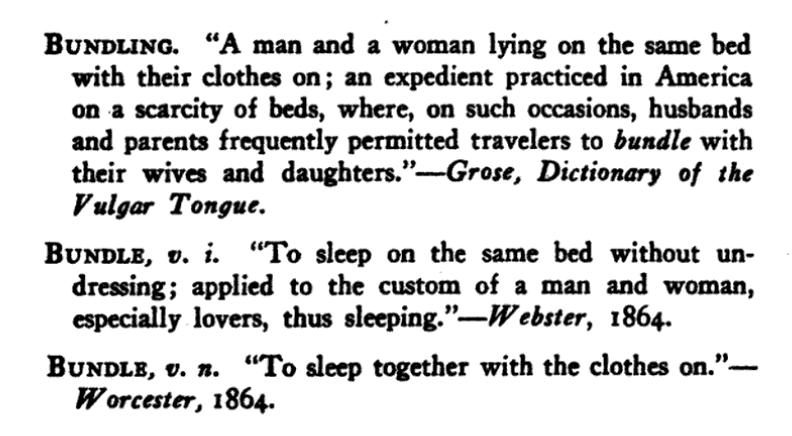

What was this “ridiculous and pernicious custom” that had tarnished so many escutcheons and was best not further “ventilated?” History of Bundling includes two definitions. From the 1788 British publication A Classical Dictionary of the Vulgar Tongue: “A man and a woman sleeping in the same bed, he with his small clothes, and she with her petticoats on; an expedient practiced in America on a scarcity of beds, where, on such occasions, husbands and parents frequently permitted travelers to bundle with their wives and daughters.” From the 1864 edition of Merriam Webster’s Dictionary (the word does not appear in Noah Webster’s 1828 or 1842 dictionaries): “To sleep on the same bed without undressing; —applied to the custom of a man and a woman, especially lovers, thus sleeping.” Its use in a sentence, from Washington Irving’s 1809 Knickerbocker’s History of New York, was: “Van Corlear stopped occasionally in the villages to eat pumpkin pies, dance at country frolics, and bundle with the Yankee lasses.”

From the 1864 edition of Merriam Webster’s Dictionary (the word does not appear in Noah Webster’s 1828 or 1842 dictionaries): “To sleep on the same bed without undressing; —applied to the custom of a man and a woman, especially lovers, thus sleeping.” Its use in a sentence, from Washington Irving’s 1809 Knickerbocker’s History of New York, was: “Van Corlear stopped occasionally in the villages to eat pumpkin pies, dance at country frolics, and bundle with the Yankee lasses.”

We begin to see what Hayden is upset about. We Connecticans look like simpletons. What husband or parent in any era would let strange men share a bed with his wife or daughter? Records of births outside or less than nine months after marriage in the colonial period show that premarital sex happened. The sharing of beds was common because beds were scarce. But the 1788 definition of bundling specifies wives and daughters. When strangers shared beds with men—was that just called sleeping? Unfortunately, the historical record appears thin, consisting of hearsay from many years past.

Though Stiles suggests that bundling died out around 1800, his defense was published in 1871, demonstrating that New England’s reputation for bundling stuck fast. Boston reportedly banned the book, but as late as the 1890s bundling remained, in the words of one historian, “a standing taint against New England morality.”

A century earlier, in October 1782, Jean-Baptiste-Antoine de Verger, a sublieutenant in the Comte de Rochambeau’s army, wrote this delightfully judgment-free description of bundling as a courtship ritual:

29 October We camped across the Connecticut River 2 miles beyond Hartford. … The inhabitants of Connecticut are the best people in the United States, without any doubt. They have a lively curiosity and examined our troops and all our actions with evident astonishment. … I can not refrain from reporting a very extraordinary custom of this charming province, which is known as “bundling.” A stranger or a resident who frequents a house and takes a fancy to a daughter of the house may declare his love in the presence of her father and mother without their taking it amiss; if she looks with favor upon his declaration and permits him to continue his suit, he is at perfect liberty to accompany her wherever he wants without fear or reproach from her parents. Then, if he is on good terms with the lady, he can propose bundling with her. This means going to bed with her. The man may remove his coat and shoes but nothing more, and the girl takes off nothing more than her kerchief. Then they lie down together on the same bed, even in the presence of the mother—and the most strict mother. If they are alone in the room and indiscreet ardor leads the man to rashness or violent acts …, woe to him if the least cry escapes her, for then everybody in the house enters the room and beats the lover for his too great impetuosity. Regardless of appearances, it is rare that a girl takes advantage of this great freedom, which confirms the good faith of these amiable citizens.

Amiable citizens, indeed.

Elizabeth Normen is publisher of Connecticut Explored. She last wrote “John E. Brockett Goes for the Gold” (Winter 2015-2016).